Welcome to the Archives of The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture. The purpose of this online collection is to function as a tool for scholars, students, architects, preservationists, journalists and other interested parties. The archive consists of photographs, slides, articles and publications from Rudolph’s lifetime; physical drawings and models; personal photos and memorabilia; and contemporary photographs and articles.

Some of the materials are in the public domain, some are offered under Creative Commons, and some are owned by others, including the Paul Rudolph Estate. Please speak with a representative of The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture before using any drawings or photos in the Archives. In all cases, the researcher shall determine how to appropriately publish or otherwise distribute the materials found in this collection, while maintaining appropriate protection of the applicable intellectual property rights.

In his will, Paul Rudolph gave his Architectural Archives (including drawings, plans, renderings, blueprints, models and other materials prepared in connection with his professional practice of architecture) to the Library of Congress Trust Fund following his death in 1997. A Stipulation of Settlement, signed on June 6, 2001 between the Paul Rudolph Estate and the Library of Congress Trust Fund, resulted in the transfer of those items to the Library of Congress among the Architectural Archives, that the Library of Congress determined suitable for its collections. The intellectual property rights of items transferred to the Library of Congress are in the public domain. The usage of the Paul M. Rudolph Archive at the Library of Congress and any intellectual property rights are governed by the Library of Congress Rights and Permissions.

However, the Library of Congress has not received the entirety of the Paul Rudolph architectural works, and therefore ownership and intellectual property rights of any materials that were not selected by the Library of Congress may not be in the public domain and may belong to the Paul Rudolph Estate.

LOCATION

Address: 23 Beekman Place

City: New York

State: New York

Zip Code: 10022

Nation: United States

STATUS

Type: Residence

Status: Built

TECHNICAL DATA

Date(s): 1977

Site Area: 2,000 s.f.

Floor Area:

Height:

Floors (Above Ground): 9

Building Cost:

PROFESSIONAL TEAM

Client: Paul Rudolph

Architect: Paul Rudolph (1977-1997); Richard Cook & Associates (2001); Della Valle Bernheimer (2004-2006)

Rudolph Staff: Donald Luckenbill, Project Architect (1977-1982); Lawrence Scarpa

Associate Architect:

Landscape:

Structural: Vincent DeSimone of DeSimone & Chaplin (1978); William T. Wheeler Company

MEP: Alexander Spielman (1978); Joseph Bressman (1978)

QS/PM:

SUPPLIERS

Contractor: Omar Building Corporation; Marco Martelli Associates (1981); Thomas Stephens Construction Corp. (2000); CW Contractors (Interior Renovation - 2004-2006); Horgan Becket (Project Management - 2004-2006); Yates Restoration (Exterior Restoration - 2004-2006)

Subcontractor(s): East Bay Iron Works (Structural Steel); Imperia Brothers (Concrete Infill Panels); Henry Y. Mann (Electrical); J-Lo and Associates (Plumbing); William A. Swartz & Son Corp. (A.C.); J & L Weissman Company (A.C. - 1978); Garden State Brickface (Exterior Stucco); Iecony Corp. & Inclinator Elevette Company (Elevator - 1981); Theodore Wagner (Plumbing & Heating - 2000); J. Callahan Consulting Inc. (Expediting - 2000); William Vitacco & Assoc. (Expediting - 2001); Charles Rizzo & Assoc. (Expediting - 2004); H & H Building Consultants (Façade repair - 2004); John Guth Engineering (Mechanical, Sprinkler - 2005-2011); Joe Ginsberg, Inc. (Interior Special Materials - 2004-2006)

Rudolph Residence - 23 Beekman Place

23 Beekman place is a 5 story brownstone constructed circa 1869 with a simply articulated principal façade, with a black metal entrance portico and a rusticated base punctuated by arched windows. Previous occupants include the actress Katherine Cornell and her stage-director husband Guthrie McClintic.

In 1955 the property is sold by Mrs. Georgia M. Williams

In 1961, Rudolph rents a 700-800 s.f. one bedroom apartment on the fourth floor of 23 Beekman Place in New York City. The owner of the building is Philomena Marsicano of the Marsicano Foundation, which had purchased the building as an investment five years earlier. Rudolph stays at the apartment on the weekends and occasionally uses it as a workspace.

In 1965 Rudolph moves from his apartment at 31 High Street in New Haven Connecticut, making his apartment at 23 Beekman Place his full-time residence. Rudolph lives at 23 Beekman Place until his death in 1997.

In the Sunday, July 23, 1967 issue of the New York Times Magazine, reporter Barbara Plumb writes, “This one-bedroom apartment may be small, but its influence is likely to be huge because the architect, Paul Rudolph, former chairman of the School of Architecture at Yale University, lives here.”

Rudolph’s first alteration of the apartment’s design includes plastic as a material for a table, built-in platforms, sliding panels and a sculpture to unify the space. The only free-standing seating is provided by white ice cream parlor chairs (Rudolph says, “They de-materialize - space goes right through them.”). To make the low-ceilinged rooms appear larger, Rudolph covers almost every surface in white, using texture rather than color to provide variety. Where there is color, it comes from segments of commercial billboard advertisements used as wallpaper (Rudolph says, “This is how you can afford great gobs of color without the expense of paintings, and each week you can afford a new one.”) He also provides opportunity to change the lighting in the apartment by putting all of the lights on separate dimmer switches “to create different psychological moods,” according to Rudolph. In the corridor leading to the bedroom from the living room which is too narrow for conventional bookshelves, Rudolph mounts his books on the wall like paintings by securing them to the wall with three L-screws. (“Now I remember books I didn’t know I had and I pick up books I’d forgotten about just because they are more visible.”) In the bedroom, the bed is covered with white sheepskin and sits on a white sheepskin rug. One wall of the bedroom is mirrored to give the small room a sense of being a larger space. Seven closets and an air conditioner are hidden behind a curtain of amber plastic beads glued to fishing line that is suspended from a track at the ceiling. A small television, unused, sits in a frame meant for a Josef Albers print. Above the bed (and reflected in the mirrored wall opposite) is a billboard advertisement for a man’s deodorant which fills the entire wall. In the living room, Rudolph uses a Plexiglas platform as seating, lighting and as a room divider. The platform is lit underneath by incandescent lights on a dimmer switch so that it appears to float above the floor. Plaster panels made from a rubber mold of a Louis Sullivan tile salvaged from the Garrick Theater (demolished in 1961) rest on steel back supports at the back of the seating platform. (The whole business of lots of legs and the usual 20th-century furniture is alien to architecture,” Rudolph says.) Curtains made of mirrors glued to fishing line are strung from a track above the window overlooking the East River. A rug of white kidskin covers the floor. A white plastic sculpture by William Ryman stands in the corner of the room. A billboard advertisement for a beverage is placed on the wall above the fireplace.

Rudolph meets Ernst Wagner, an exchange student from Switzerland who is studying at Columbia University. Wagner moves into 23 Beekman Place in October 1975.

Edward B. Schoen (19xx-1989) - Rudolph’s lawyer - calls Rudolph while he is overseas on a business trip in the Far East and tells him that the Marsicano Foundation is going to sell the building and - because they like Rudolph - are motivated to sell it to him. Rudolph, unsure he can afford to buy the building, calls Wagner from Paris on his way back to New York. He tells Wagner that there is another person looking to make an offer on the property and asks Wagner what he should do. Wagner tells Rudolph that since he can afford to put down $100,000, he should buy the building.

In June, 1976, Paul Rudolph purchases 23 Beekman Place for $300,000 from the Marsicano Foundation of New York City. Rudolph pays $100,000 in cash, getting a personal mortgage from the Marsicano Foundation and borrows the rest from a private-equity manager.

In July, 1976 Rudolph submits a set of construction drawings to New York’s Department of Buildings for a $120,000 alteration which radically challenges the New York City zoning code, and particularly the tastes and conventions of the neighborhood, which is home to some of Manhattan’s wealthiest residents. Plan examiners object to the proposed height and enlargement of the second, third and fourth floors by as much as 25 percent. Alfonso Duarte, Rudolph’s engineer for the project, argues before the Board of Standards and Appeals that it “was not feasible or practical nor even economical to erect a new comparable structure on the site” and that precautions that were proposed during construction would result in improved safety. Donald Luckenbill, who worked in Rudolph’s office from 1969-1982, met with plan examiners several times during 1976 and 1977.

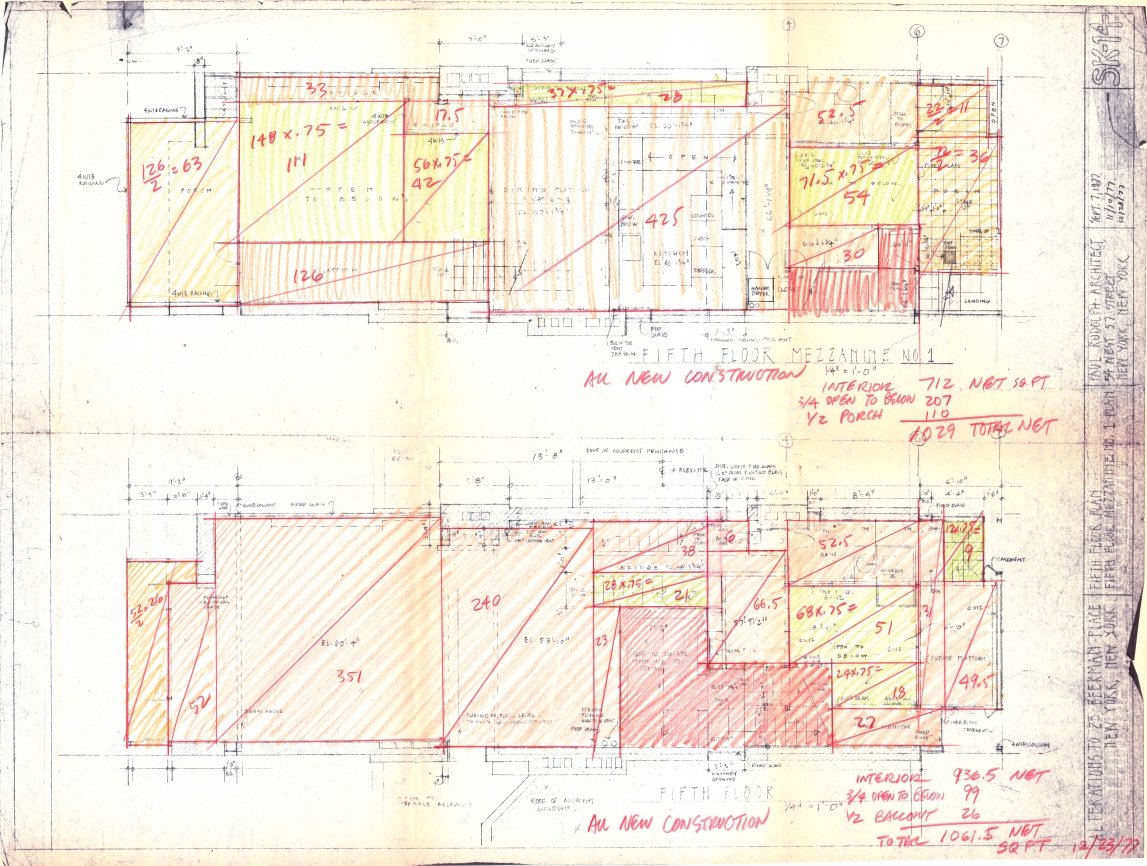

The proposed renovation and addition adapts to the existing brownstone building below by adding seventeen feet of living space and terraces above the existing parapet line; and cantilevering a total of an additional 1,000 square feet (distributed among all floors) beyond the townhouse’s existing East façade.

The penthouse, also known as the Quadruplex, is arranged on four interconnected levels. Entered from the main stairs near the west end of the sixth and seventh story, it contains a two-level guest suite that faces Beekman Place (used by Mr. Wagner). That space is composed of a series of terraces with surreally open (and desirable) views of the East River and Roosevelt Island. In total, there are estimated to be seventeen levels in the four story design. The resulting Quadruplex, within the upper level and atop the existing building, manifests Rudolph’s unique and paradoxical stance relative to preservation and urbanism.

Several of Rudolph’s design proposals, including window-less rooms and a roof-top swimming pool are rejected by the building department.

The Board of Standards and Appeals grants a variance for the project in February 1977 and a Department of Buildings permit is issued in June 1977.

The first phase of the addition consists of rebuilding portions of the original brick party walls which are determined unsafe.

The penthouse addition is constructed during late 1977 and 1978 using steel supplied by East Bay Iron Works (located in the Hunt’s Point section of the Bronx) and concrete infill panels manufactured by Imperia Brothers of Pelham Manor, NY.

The rear façade of the building is demolished and a new steel-and-glass façade is erected that at parts extends out by as much as 17-1/2 feet. In addition, a rooftop addition is designed to support multiple mezzanines, terraces and cantilevers. The front façade of the addition extends beyond the original building by five feet, matching the areaway below.

By the end of 1978 most of the interior work on the rental apartments is complete and the materials to construct the penthouse are being raised to the fifth floor.

In the December 1978 issue of GA Houses, Rudolph notes by then he had lived in the 800 square foot apartment for “approximately 15 years” and that “three small windows facing the river, Roosevelt Island, and industrial Queens were replaced by a glass wall with doors opening onto a small terrace.” Regarding the original one bedroom unit, “the apartment no longer exists, but it was never more than a series of sketches, or studies, for other projects.”

A temporary Certificate of Occupancy is issued for the building in 1979 until 1980.

Instead of extending the existing building elevator, Rudolph adds a private elevator by Iecony Corp. & Inclinator Elevette Company in 1981.

A final Certificate of Occupancy is issued in January 1982.

In 1984 Rudolph draws sketches for a proposed tower to be constructed adjacent to 23 Beekman showing the existing 23 Beekman property incorporated into the footprint of the new tower. The tower proposal is never constructed.

Paul Rudolph passes away on August 08, 1997.

On June 01, 1998 the residence is listed for sale by the Paul Rudolph Estate for $6,250,000 USD by Frederick J. Williams of Sotheby’s International Realty. Mr. Williams studied architectural history in the Rudolph-designed Charles H. Dana Creative Arts Center at Colgate University.

A viewing of the listing is hosted by the Architectural League.

The residence eventually gets six to eight serious offers. One of the offers is from a developer who plans to gut the penthouse and turn the building into five condominiums.

On May 01, 2000 the building is sold by the Rudolph Estate Co-Executors Thomas Heckman and Ernst Wagner to Gabrielle and Michael Boyd for $5,500,000 USD. After taking possession of the property, Michael Boyd tells the New York Times “We want to be guinea pigs for the experiment of living in this place.” The Boyds tell the paper they plan to take up full-time residence in the penthouse in June, when their children complete school for the year. The Boyds credit Joseph Holtzman, editor in chief of Nest magazine, for setting up the real estate transaction. Mr. Holtzman tells the New York Times, “Michael Boyd is the perfect person to take over the Rudolph house. He is the most intelligent collector of Modern design I have ever met. His collection will make a significant addition to New York’s resources. As far as the house goes, Michael both understands and respects the architecture, and will preserve it as a rather large object in his own collection.”

The Boyds initially expect that the house would be sold to them with all of Rudolph’s furnishings and artworks intact, but the estate is in probate at the time of the sale and Rudolph’s personal property and furniture had been removed. Mr. Boyd tells the New York Times, “We’re hopeful that at some point we’ll be able to bring the work back into the house to restore it as closely as possible to Rudolph’s original intention.” The Boyds tell the paper that they plan to clean up and paint the house, but there will be no renovation beyond rebuilding one wall in the Master Bedroom which Rudolph removed when he became infirm. They state they are planning to eventually open the home to scheduled tours and possibly open their own collection - to be located on the lower floors of the building - to the public as well. The lower floors of the building will be used to house their furniture collection as well as for recreation rooms for the family.

On August 30, 2000 All Safe Height files for a permit to erect a sidewalk shed during façade repair.

On September 29, 2000 Donald Luckenbill files construction drawings for an interior renovation of the existing residence and installation of new roofing. The permit is approved on October 13, 2000. Thomas Stevens Construction Corp. is the general contractor for the work. Theodore Wagner Plumbing & Heating does the MEP work.

The Boyds transform Rudolph's penthouse plus the floors below it into a house museum to display their collection of 20th-century Modern furniture and artworks. The Boyds also make changes to Rudolph’s original interiors: they strip off chromed laminate applied to steel beams and columns to match the stainless steel in the floor, they put Sheetrock under the Plexiglas tub hanging above the entry and part of the kitchen. To keep visitors (and residents) from suffering vertigo, they partially enclose the sides of the floating stairs with vertical white-frosted-acrylic panels, and replace the clear acrylic floors of the bridges with a translucent version. Many of the reflective and transparent planes and lines disappear into the new, stark white interior.

On March 16, 2001 Richard Cook & Associates files construction drawings to combine two of the existing rental apartments into a single apartment, creating a new convenience stair and removing a kitchen. The permit is issued on March 19, 2001 and the work signed off on October 31, 2001. Thomas Stevens Construction Corp. is the general contractor for the work. Theodore Wagner Plumbing & Heating does the MEP work.

On December 12, 2002 the building is sold by Gabrielle and Michael Boyd to Stephen Campus of Rupert LLC for $6,325,000 USD.

Kossar + Garry Architects, LLP is hired by Mr. Campus to renovate the penthouse. A construction permit for the work is issued on May 11, 2004 and Charles Rizzo & Associates is the expeditor. The description of the work is “replacement of existing toilet fixtures and minor work on the 4th floor, 4th floor mezzanine, 5th floor, 5th floor mezzanine #1 and 5th Floor mezzanine #2.

In 2004, after halfway through a substantial demolition and renovation of the penthouse interior, the owner consults the general contractor - CW Contractors - and decides to hire architects Jared Della Valle and Andrew Bernheimer to continue to renovate the building, including structural work and exterior renovations. Della Valle Bernheimer and CW Contractors work hand in hand to modify the spaces for the present owner's needs while saving as much of Rudolph's concept as possible. The architects create what they call “the contemporary progeny of Rudolph's designs.” They study and reinterpret his design principles and speculate about how Rudolph might have continued his experiments if he'd had modern innovations and the newest technology at his disposal. A revised permit is issued on May 02, 2006 which replaces Kossar + Garry Architects, LLP with Della Valle Bernheimer as architect of record along with a revised set of construction drawings.

A lot of Rudolph’s original design had been lost already, including finishes that had not aged well, such as carpeting, Sheetrock, and melamine. The architects bring in Joe Ginsberg, Inc. to provide items such as mirror-finished stainless steel and acid-etched, brushed, and sandblasted glass, as well as new details, such as hardware. Ginsberg uses finishes that resemble Rudolph's original choices; for example, the company gives the new wood cabinetry a varnish coating that recreates the look of melamine. Where the owner wants to keep the stainless-steel plates on the floors in the guest bedroom and media room, Ginsberg matches the aging stainless with a version that won’t appear jarringly brand-new. The architects keep the translucent acrylic bridges from the previous renovation, because the client wants to avoid the expense of going back to clear acrylic. Della Valle Bernheimer removes Rudolph’s personal elevator and seals the shaft with clear acrylic to create a transparent light well running vertically through the apartment. The architects raise Rudolph's low seating areas that nearly sat on the floor. Instead of carpeting, they install an epoxy surface with a sheen echoing the waters of the East River outside. To fend off vertigo, the architects substitute vertical screens of parallel stainless-steel cables with rivets along the edges of stair treads (not unlike Rudolph had used on some of his residential projects), which are more transparent than the vertical louvers enclosing the stairs in the Boyd renovation. Clear glass panels form the mezzanine balustrade instead of the white, frosted acrylic used by the Boyds, or the gleaming acrylic used by Rudolph. Other changes involve reconfiguring the kitchen and redoing the bathrooms with new plumbing and electrical fixtures, along with solid-surface counters and cabinets. The master bath is enlarged, although the owner keeps it in the same location. For the façade, the architects discover structural beams in the cantilevered portion over Beekman Place are sagging, so new steel in inserted within the webs of the I-beams and re-weld them to shore up Rudolph’s addition. Steel framing members are also replaced on the rear façade of the building, facing the East River. When finally complete, the construction takes 20 months.

On May 27, 2004 H & H Building Consultants, Inc. files for a permit to erect a sidewalk shed during façade repair. Another permit is issued on August 25, 2004 and again on December 29, 2004.

On February 14, 2005 John Guth Engineering files for a permit to make mechanical and sprinkler changes on the 5th floor and the roof. The work is signed off on January 31, 2011 and Charles Rizzo & Assoc. is the expeditor.

In a September 28, 2006 article in New York Magazine, the previous owners, Gabrielle and Michael Boyd, confess to being “saddened” after hearing of the renovation.

In February 2007 the New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects presents an Architecture Honor Award to Della Valle Bernheimer for their work in modernizing 23 Beekman Place.

On November 17, 2009 the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission holds a hearing on the proposed designation of the Paul Rudolph Penthouse & Apartments and the proposed designation of the related site. Three people speak in favor of the designation, including Docomomo New York/Tri-State, the Historic Districts Council, and the Paul Rudolph Foundation (then led by Ernst Wagner, who had founded the organization in 2002). Community Board 6 takes no position at the time of the hearing, and a representative of the property owner requests that the public record remain open for a period of thirty days.

On November 16, 2010 the Paul Rudolph Penthouse & Apartments located at 23 Beekman Place is designated a New York City landmark (# LP-2390)

“It’s hard to be depressed in here.”

“For approximately 15 years I have occupied an 800 square foot apartment overlooking the East River. During this period its constrictions were modified in various ways. Three small windows facing the river, Roosevelt Island, and industrial Queens (complete with its 40’ x 90’ neon signs) were replaced by a glass wall with doors opening onto a small terrace. ”

“... even Paul Rudolph’s new attic on his house at No. 23 (1978) plays a role in the total composition. (The Rudolph house, incidentally, has been strongly criticized by its neighbors, who seem to have forgotten that their street is a mix of different styles put together over time. Still, it is a forceful intrusion, and acceptable though the vertical extension is in principle, it is hard not to wish that Mr. Rudolph had not been willing to show a bit more restraint in his overall massing, which cantilevers over the front of the existing townhouse.)”

“The fact of the matter is that becasue of the cantilevers you don’t see into the building much. You see underneath the building.”

“It is easily one of the most amazing pieces of modern urban domestic architecture produced in this country, a structure packing more finesse and design wallop in its compact volume than many architects manage to produce over entire careers.”

“The rooftop at Beekman Place enjoys its place in the sun, partially because a zone of space created by steel columns and beams supporting wisteria on trellises protects the inner space. This intermediate zone acts as a buffer between the interior spaces, the noisy city close by, and the brilliant sun overhead.”

“I really admired the fantastical quality of the place. I’ve never minded thumping my head on architecture - I’ve had cuts from Schindler and Wright in the past.”

“Rudolph is an enigmatic character. He’s an exact contemporary of Marcel Breuer, Craig Ellwood and Arne Jacobsen, all of whom did really great early high Modernist work and then went on to gain a language of their own that was completely stunned by the arrival of postmodernism.

What most people think of as Modernist today is highly simplified. There are figures like Rudolph, Joseph Cornell, Frederick Kiesler, Hans Bellmer and Carlo Mollino who practiced a more quirky, eccentric and frankly sexual brand of Modernism that isn’t associated with the sterile German buildings many people think of as defining the movement.”

“What we’re really excited about is to wake up every morning and be inspired by this place. How many people get to live in a Constructivist sculpture?”

“It’s a view inside his mind: clear but so complex.”

“We challenged ourselves to the limit. Without mimicking him, we took what he created to generate something new - yet stay true to the idea.”

“As you may know, Paul Rudolph passed away last summer, leaving behind a legacy of architectural work which will live on throughout history. Some of you have the privilege of owning and occupying one of Mr. Rudolph’s creations. All of you know the warmth and passion which Paul Rudolph instilled in his work.

Perhaps Paul Rudolph’s most personal project was his own home in Manhattan, where he lived throughout his final years. His penthouse apartment at 23 Beekman Place was an architectural laboratory where he constantly tested new architectural ideas and new details. Anyone who has seen his apartment knows what an ideal representation of Paul Rudolph’s architectural vision the apartment is.

Mr. Rudolph’s estate is now offering the home for sale. Paul Rudolph hoped that his own penthouse apartment could be preserved for posterity. A description of the property is enclosed. If you have an interest in this property or in helping preserve Paul Rudolph’s own penthouse apartment, or if you wish to discuss any aspect of this property, please contact me.”

“On the basis of a careful consideration of the history, the architecture and other features of this building, the Landmarks Preservation Commission finds that the Paul Rudolph Penthouse & Apartments at 23 Beekman Place has a special character, special historical and aesthetic interest and value as part of the development, heritage, and cultural characteristics of New York City.”

“He wanted natural light to pour through, top-to-bottom, and he was always playing with ways to achieve that. You just have all these amazing spaces floating inside this giant apartment.”

“Rudolph is often described as Brutalist, but there’s nothing severe or somber about the space. The thrusting

I-beams, canopied walkways, and floating stairs create these beautiful social and living areas. And though the design looks so new, it really fits into the older building.”

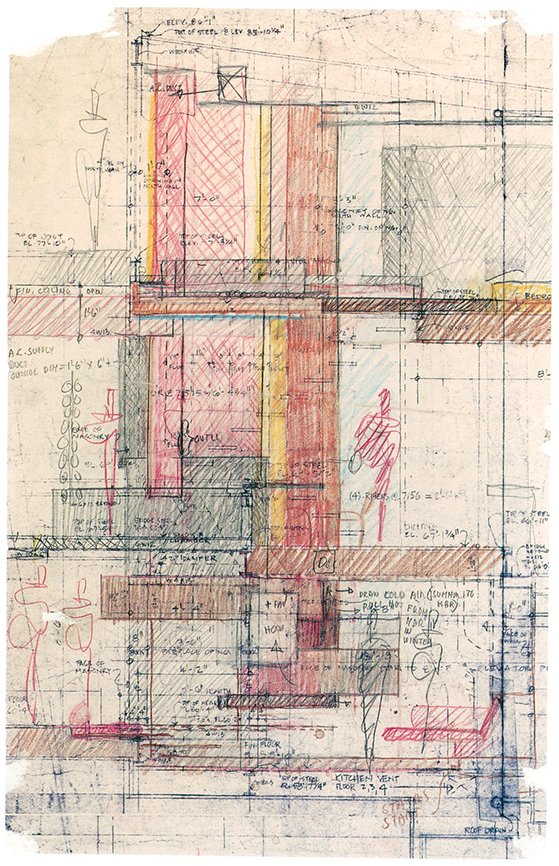

DRAWINGS - Design Drawings / Renderings

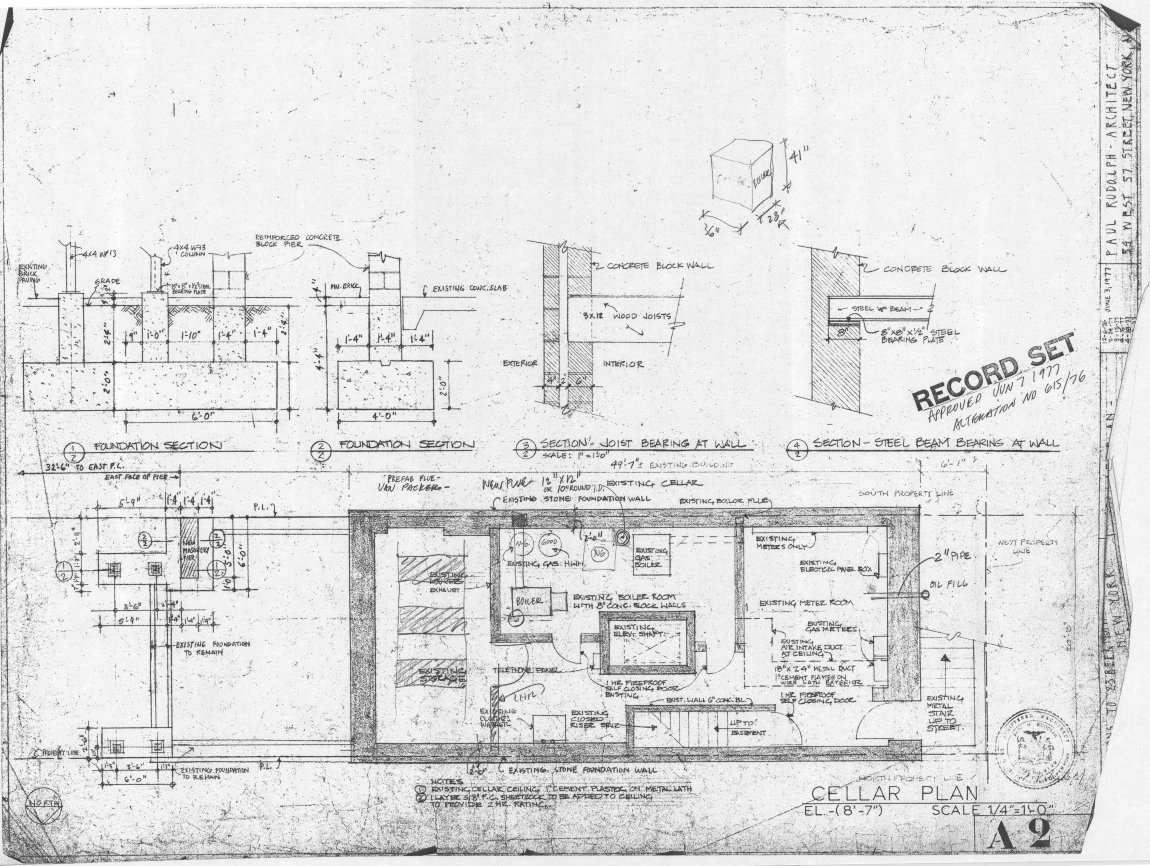

DRAWINGS - Construction Drawings

DRAWINGS - Shop Drawings

PHOTOS - Project Model

PHOTOS - During Construction

PHOTOS - Completed Project

PHOTOS - Current Conditions

LINKS FOR MORE INFORMATION

RELATED DOWNLOADS

Landmark Designation Report - NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, November 16, 2010

PROJECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Akiko Busch. Rooftop Architecture: The Art of Going Through the Roof. 1st Edition, Henry Holt & Company, 1991.

Alexandra Lange. “How to Save a House.” Town & Country, Apr. 2021, pp. 74–77.

---. “Paul’s Boutique.” New York Magazine, 13 July 1998.

Barbara Plumb. “Paul’s Pacesetter.” The New York Times, 23 July 1967.

Bonnie Schwartz. “A Modern Masterpiece Becomes Child’s Play.” The New York Times, 4 May 2000.

Charles Hoyt. Interior Spaces Designed by Architects. 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill, 1981.

Colin Davies. Key Houses of the Twentieth Century: Plans, Sections and Elevations. W. W. Norton & Company, 2006.

Daniella Ohad. “Michael Boyd on the Pioneers of Modernism.” Design Miami, 2020.

David Hay. “The Beautiful Headache.” New York Magazine, 28 Sept. 2006.

George Rush. “The Nastiest Neighbor Renovation Feuds in New York.” Avenue Magazine, 21 May 2021.

International Style: The Boyd Collection. Wright20, 2018.

Jane Withers. Hot Water: Bathing and the Contemporary Bathroom. Soma Books, 1999.

Joseph Giovannini. “An Architect’s Last Word.” The New York Times, 8 July 2004.

Ken Tadashi Oshima and Toshiko Kinoshita, editors. “Rudolph House.” Architecture and Urbanism, Oct. 2000, pp. 260–71.

Kenneth Frampton. American Masterworks: The Twentieth Century House. Rizzoli International Publications, 1995.

“Kinetic Electric Environment.” Progressive Architecture, no. 49, Oct. 1968, pp. 198–206.

“La Casa Di Un Architetto.” Domus, no. 575, Oct. 1977, pp. 36–38.

Linda Yang. “An Architect Raises a ‘Green Mansion’ Above the East Side.” The New York Times, 30 June 1988.

---. The City Gardener’s Handbook: From Balcony to Backyard. Random House, 1990.

Mary Gilliatt. Decorating: A Realistic Guide by Mary Gilliatt. Pantheon, 1977.

Matt A. V. Chaban. “In Era of Iconoclasts, Imagination Took Wing on Beekman Place.” The New York Times, 8 Sept. 2014.

Michael Sorkin. “The Light House: Paul Rudolph’s Triplex Aerie Suspended over the Manhattan Skyline.” House and Garden, vol. 160, no. 1, Jan. 1988.

Paul Goldberger. “Architecture: Show of Rudolph’s Work.” The New York Times, 5 July 1979.

Paul Rudolph: Explorations in Modern Architecture, 1976-1993. National Institute for Architectural Education, 1993.

“Paul Rudolph, N.Y. Apartment, New York, N.Y. 1977-78.” Global Architecture Houses, no. 6, 1979, pp. 88–89.

“Paul Rudolph, Paul Rudolph Apartment, New York City, U.S.A.” Global Architecture Houses, no. 5, 1978, pp. 106–09.

“Record Interiors of 1978.” Architectural Record, no. 163, Jan. 1978, pp. 77–79.

Richard Geary. “Thinking Inside the Box.” Florida Design Review, no. 2, 2007.

Robert Bruegmann and Mildred F. Schmertz. Paul Rudolph: Dreams + Details. Steelcase Design Partnership, 1989.

Roberto De Alba. Paul Rudolph: The Late Work. Princeton Architectural Press, 2003.

Smith, Ray. “Designers: Floating Platforms.” Progressive Architecture, no. 48, May 1967, pp. 149–51.

Suzanne Stephens. “Della Valle Bernheimer’s Thoughtful Renovation of the Paul Rudolph Penthouse in New York Rises from His Original Intentions.” Architectural Record, vol. 195, no. 6, June 2007, pp. 116–21.

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation. Paul Rudolph: The Personal Laboratory. The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, 2019.

Thomas Mellins. “An Architect’s Home Was His Modernist Castle.” The New York Times, 21 June 1998.

Timothy Rohan. The Architecture of Paul Rudolph. Yale University Press, 2014.

Wendy Moonan. “A New Breed of Aficionado Comes of Age.” The New York Times, 17 May 2002.

“White-on-White, Its Optical Surprises.” House Beautiful, no. 109, Sept. 1967, pp. 148–49.

William Menking. “Manhattan Masterpiece.” The Architects’ Journal, 28 Oct. 2004.