Welcome to the Archives of The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture. The purpose of this online collection is to function as a tool for scholars, students, architects, preservationists, journalists and other interested parties. The archive consists of photographs, slides, articles and publications from Rudolph’s lifetime; physical drawings and models; personal photos and memorabilia; and contemporary photographs and articles.

Some of the materials are in the public domain, some are offered under Creative Commons, and some are owned by others, including the Paul Rudolph Estate. Please speak with a representative of The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture before using any drawings or photos in the Archives. In all cases, the researcher shall determine how to appropriately publish or otherwise distribute the materials found in this collection, while maintaining appropriate protection of the applicable intellectual property rights.

In his will, Paul Rudolph gave his Architectural Archives (including drawings, plans, renderings, blueprints, models and other materials prepared in connection with his professional practice of architecture) to the Library of Congress Trust Fund following his death in 1997. A Stipulation of Settlement, signed on June 6, 2001 between the Paul Rudolph Estate and the Library of Congress Trust Fund, resulted in the transfer of those items to the Library of Congress among the Architectural Archives, that the Library of Congress determined suitable for its collections. The intellectual property rights of items transferred to the Library of Congress are in the public domain. The usage of the Paul M. Rudolph Archive at the Library of Congress and any intellectual property rights are governed by the Library of Congress Rights and Permissions.

However, the Library of Congress has not received the entirety of the Paul Rudolph architectural works, and therefore ownership and intellectual property rights of any materials that were not selected by the Library of Congress may not be in the public domain and may belong to the Paul Rudolph Estate.

LOCATION

Address: Lally Lane

City: Hamilton

State: New York

Zip Code: 13346

Nation: United States

STATUS

Type: Academic

Status: Built

TECHNICAL DATA

Date(s): 1963-1966

Site Area:

Floor Area:

Height:

Floors (Above Ground): 4

Building Cost: $1.5 million USD ($26.50 / s.f.)

PROFESSIONAL TEAM

Client: Colgate University

Architect: Paul Rudolph

Associate Architect:

Landscape:

Structural: Milo S. Ketchum & Partners

MEP: Van Zelm, Heywood & Shadford

QS/PM:

Theater Equipment: Edward C. Cole

Theater Lighting: Harvey K. Smith

Theater Acoustics: Cambridge Acoustical Consultants

SUPPLIERS

Contractor: Ryan - McCaffrey Corp.

Subcontractor(s):

Charles H. Dana Creative Arts Center for Colgate University

In 1962, Charles A. Dana, noted industrialist and philanthropist, visits the campus of Colgate University and after observing art classes and studios in basements of class buildings, sees a need for a Center which would provide the right atmosphere for the creative arts at the university. He challenges, through the offices of the Dana Foundation, the college to find matching funds to supplement an initial grant of $400,000. Hundreds of volunteers accept the challenge to raise the necessary funds.

A Center for the Creative Arts becomes possible with the creation of a faculty committee under the chairmanship of Dr. Herman Brautigam and composed of representatives from the various art departments set to work on formulating a program for the building. The committee has $1,200,000 to work with for a budget.

The committee, according to Dr. Brautigam, had ‘three or four’ architects in mind, with the choice of an architect being its first consideration. Mr. Arthur Watson, a member of the Board of Trustees, suggests Rudolph after being impressed with the Mary Jewett Arts Center at Wellesley College and the chapel at Tuskegee Institute. Dr. Brautigam also favors Rudolph, and although not all of the other members agree, Rudolph is finally the one chosen to receive the commission.

Rudolph comes to the campus and finds “one of the most handsome campuses in the country.” He engages in preliminary discussions and leaves with a detailed list of the building’s needs and a working budget.

The project scope is to design Colgate’s University’s first creative arts building. At the time, it is simply known as the Creative Arts Center.

The building’s program calls for a building that is to create a focal point for the fine arts, make them as important as other activities on campus, and establish a creative environment for a rural college that has no museum, theaters, galleries, etc. The preliminary specifications are ambitious: the faculty wans complete facilities for graphics, painting, music and drama courses and space for an art collection. In addition, the University wants to promote an integrated study of the arts, which requires classrooms with special audio-visual equipment, and small rooms with special computer equipment to encourage individual experiment and creativity.

Rudolph later returns to walk the campus and study the architecture that has reflected almost 150 years of growth and redevelopment at the university. With a site in mind, Rudolph returns to his office to sketch a building that would fit into the terrain, relate to the existing campus, fit the flow of student traffic, and house the creative arts.

The building Rudolph designs for the site is striking and original, yet compliments the existing campus architecture. The angular roof repeats the contours of other rooftops on the hill, the location of the building effectively extends the lines of the quadrangle, and the texture as well as the color of the new building represents a modern interpretation of the stone that has become too expensive. Close to the classrooms and the library, easily accessible, but separated enough to command its own setting, Rudolph’s plan meets both practical and aesthetic requirements of the project.

The initial program is overambitious for the budget of $1,200,000 and is cut severely. The concert hall, graphics, sculpture and painting facilities are all to be located in a “second” section of the project, which the administration does not foresee building until “a couple of generations of students have gone by.” Meanwhile, the auditorium doubles for both music and drama; schedules frequently overlap. Gallery space and the classroom requirements for the special studies are fulfilled, but the experimental studios are eliminated.

According to Rudolph, the original plan was “for a staged building project with the possibility of two or three, or as many as five stages.” The first stage is to be the main stage, and the other further additions are postponed due to budgetary limitations. According to Dr. Brautigam, Rudolph had some very specific ideas for a second stage which never materialized.

Rudolph states he “was given as free a hand as possible.” “They were really quite wonderful,” he says, “but of course there were budgetary and other restraints.”

The choice of the project site, according to Dr. Brautigam, “was left pretty much up to Rudolph himself.” According to Rudolph, “the site was very significant for the whole structure.” Adding, “It is intended to be both a symbolic gate to the campus and to effect a connection between the upper and lower parts of the campus.” “I don’t believe in inspiration,” he says, “but I felt it was a remarkable site.” He continues, “the older buildings on campus were my point of departure, and my building was intended to reflect the silhouettes of the earlier buildings.”

Acoustically, the building works with padded ceilings and carpeted floors deadening the sound. The irregular walls of the small music rooms prevent undesirable reverberations. The only complaint is that the organ room cannot be used at the same time as the auditorium, because sound travels through the ventilating system.

The building’s structural design consists of a concrete frame with precast concrete block infill. The roof over the auditorium is post-tensioned steel supported by a 34-foot angled beam which also serves as an exterior wall. The cast-in-place concrete frame has a 3” board texture, and the concrete block is fabricated in pairs and then split, creating a custom rough “corduroy” texture. The original structure was to be entirely cast in place, and concrete block was used to cut cost.

The building’s mechanical system is a zoned air system for heating and ventilating which is supplemented by perimeter fin hot-water radiation. Heat is supplied to conversion units from an existing university steam system. There is no cooling system.

The roof of the building adjoins a hill providing access to the first and fourth floors, and is designed so it can be used as a gallery for sculpture and art shows

The roof design also features several dormers to provide natural light for art studios and classrooms and to blend with the lines of the Student Union building situated to the immediate right of the building.

On April 09, 1964, Colgate University presents the plans to Charles A. Dana and architectural critics at the University Club. According to a New York Times article that covers the event, everyone expresses admiration for the plans except Mr. Dana. He suggests that the principal architectural feature of the building, a three-story massive port-cochere, be removed and that the site be changed. Rudolph, who is also at the event, tells Mr. Dana that the design change would ruin the building. He says the port-cochere shelters the building’s entrance and bears an extension of the fourth floor in which a painting and sculpture studio will be located. He concludes it will have the additional value as a gateway to the old Colgate quadrangle of traditional buildings, seen up a hillside, with the spire of the chapel in the center. Mr. Dana, after Rudolph finishes, asks him, “You are one of the drawers of this building?” He then asks about the proposed footbridge behind the building which connects the back of the building with the old quadrangle at the top of the hill. “Why have that bridge? Walking is good for students.” Rudolph acknowledges that the bridge is an optional addition that could be removed from the design. Mr. Dana tells everyone he approves the various features but asks to hear more about the port-cochere. He finishes by advising, “You can save money on these extremities.” University officials explain there were reasons to not change the site but agree to examine Mr. Dana’s suggestion.

The building is occupied in January, 1966.

On September 08, 1966 Rudolph delivers the speech ‘Urban Design’ at the annual Founders Day Convocation about urban planning and the basic elements that need to be expressed in urban design. After the address, members of the administration award Rudolph with an Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts Degree. The honor is presented by Dr. Herman A. Brautigam, Henry Emerson Fosdick Professor of Philosophy and Religion along with university President Vincent M. Barnett, Jr. According to the school newspaper, only on one previous occasion has the University awarded a similar degree in 1959.

In 1972 Mr. Brooks Stoddard, Chairman of the Fine Arts Department, decides to review the original proposal to build Phase 2 of the project due to feeling the pressure of limited space in the original Rudolph building. After looking at the possibility to rehabilitate the Old Biology building, a decision is made to construct a new but inexpensive building for $300,000 to provide studio space next to the original Rudolph building. “It was our feeling,” said Stoddard, “that the Rudolph building itself was such a strong structure that it could withstand the presence of another structure nearby, even though it would be nice to keep it isolated. I think the academic realities are that students are coming here, they need space to work in, and it makes sense to have them working in an area with some proximity to the other arts.”

Two architects are considered for the studio building, and a local Utica firm is given the contract. Although a simple loft building, there is an attempt to maintain a style similar to that of the original Rudolph building. The splitface concrete block is one example of this effort. “The judgement of history will show how that studio building relates to Dana,” says Mr. Stoddard. “I rather think it does.”

In 2011 the Picker Art Gallery exhibits Chris Mottalini’s photographs of demolished Rudolph works entitled, After You Left, They Took It Apart.

In 2018 Dean Lesleigh Cushing announces that the university plans to renovate the Dana Arts Center, with the aim to increase the visibility of the arts in Colgate’s curriculum. A series of open forums and meetings with Student Government Association are proposed. The plan is to construct multiple new buildings in the area around Rudolph’s building to alleviate the needs for additional space as the result of the expansion of the university’s arts program.

“The Colgate Theater has some of the features of an Elizabethan theater: four side stages (two levels on each side) and an apron that projects into the audience in a V form. The stage continues in front of the side stages, and along the sides of the audience. It is the level you actually enter on. Part of my notion is that when you enter the theater you are on the stage, and then you go down and take your seats.”

“Functionally, its elevated wing contains artists’ studios; clerestories just up above the roof line to catch the light; galleries and staircases are cantilevered out into space; practice rooms on the ground floor declare themselves by irregular shapes, which baffle the sound. ‘I’m not looking for beauty,’ said Rudolph ‘but I’m looking for what’s meaningful.’”

“It went completely against my ideas of a building and the traditional college campus. But as time went on, and I travelled through it over and over again, I felt there was something I was missing. Each entrance into the concrete monster made me more and more aware of my lack of appreciation for it. Then, one day, a professor mentioned the idea of spatial surprise and that was the key: the way the building is laid out to keep the senses alive as you walk through it. Each new passage, stairway, or turn brings the unexpected: a quick upward rise to the sky or a rapid drop to the pavement below, a cramped pass that breaks out into great light, or the feeling of being drawn into the many nooks and crannies with a sort of suction as you turn the corner. It still doesn’t fit on campus, but of all the college buildings, it’s the only one that makes me feel alive when I enter it.”

“We think too much of the building as an entity within itself. The Parthenon depends on its sitting atop the Acropolis; on the sequence of spaces revealed as one approaches; on its mysterious relationships to the form of the mountains beyond; and on the eternal and incomparable clarity of sunlight. All of these elements blend and interact so that finally the ensemble becomes the symbol for the age.””

“One cannot escape being impressed by the largeness of the structure. It looks by far the largest building on campus and has been variously described as a fort, or an ICBM silo.

It has put a blemish on the campus.

One look across the lawns at the hard gray lines and you read man. It doesn’t just sit there on the side of a hill, but stands there proudly - and thus challenges me.

It is a formidible structure with a courseness and strength which many see as a part of that nebulous person - the Colgate man.

My first reaction was to explore it.

It is fascinating and forbidding. Its daring and imagination breed a marvelous curiosity, while the sharp edges and unpredictable shape make it seem alien and uninviting.

It tempts you to use the stairs instead of the elevator.

There is no feeling of ground or second-floorness because of the integration of the levels with semi-levels. There is no tiring from climbing stairs because of this.

He has reworked the redundant regularity of a thousand rooms and consistent horizontals and verticals. The rooms and hallways are not placed at right angles but only and exactly where they are needed. This results in a continual break-up of consistency.

Rudolph has devised a follow-the-dots game in which every stop holds some sort of architectural surprise: the multi-shaped windows, unique room shapes, and the various studios are so well conceived that, after two years in the building, I still find something new everyday.

Every hallway, staircase, classroom, listening room - from the theater to the john - has some fascinating innovation for the imagination to play with.

Everyone has a favorite area: a certain window; or ceiling, hallway, wall or corner. Rudolph said that the balcony over the main entrance was where boiling oil could be poured on the enemy.

The somewhat stark, foreboding exterior suddenly becomes quite comfortable inside. The concrete has nothing of the harshness you would anticipate, and you feel almost compelled to touch it to be sure.

This building challenges you to walk through it without being forced to run your hands across the sandpaper walls, the cotton (acoustical) ceiling, or the stone floors, not to feel some reaction to the building. It is becasue of this that the Art Center is organic: it makes you come and observe it - both mentally and physically. This separates it from most buildings: you are aware of the structure you are in and take notice of it; you don’t walk up and down stairs with your feet; you pass from floor to floor with your eyes, hands, and mind as well.

The building asks you, ‘How did he approach making it. Why did he use this material, in this unusual way?’

Many buildings, while still locked in the molds and braces of construction, are more surprising and certainly more exciting than the cut-and-carpeted end products. Not so here. This stands as a resilient experiment in soft concrete, a no-holds-barred writhing of highly textured planes that beckon the passing hand.

I have often felt that being in this building is like being backstage when you are able to see the open spotlights and fixtures. You feel a new proximity to the performers and the artists. I think it is the Center itself which puts you in this frame of mind.

Initial suspicion and dislike of the unfamiliar or spontaneous approval are finally irrelevant in view of the active awareness that such a structure generates.

It makes every performance a little more spectacular, keeps the show going on even during intermission, and involves audiences in the performances. The spirit of the building is very flexible - not that it provides an anonymous background suitable to any kind of activity, but an active environment for various kinds of activities. It challenges everybody; enjoys a round of Cowboys and Indians with local children; causes students to be more critical of the exhibits; helps us relax, and forces us to create. The Arts Center provides a new perspective at Colgate - mentally and physically.”

“I would have preferred Aalto as an architect. The rolling hills and woods need a softer touch and material.

It’s an excellent building to teach the history of architecture in; it has everything. I can find examples for all sorts of styles.”

“The first and largest scale is that of the broad outlines of the structure, which relate the building to the landscape, tie it to the campus behind, and the town beyond. From the main road, the structure appears to be a giant one-story building with huge collumns. The roof matches the sweep of the playing field in front, the archway is a grand port-cochere to the campus and frames the cupola of the old chapel beyond. As the visitor approaches the building, a smaller scale becomes apparent: the individual floors and rooms are articulated, the human dimension expressed. The next order down is the concrete block - hand size; then the corrugated texture - fabric size.”

“The American genius for building throughways, bridges, intersections, rendered almost voluptuous as a Rubens painting, are deep in the American tradition of going on, on, on.”

“Quickly, everyone grows tired of the package. The principal alternate to package architecture grows out of Frank Loyd Wright’s and Le Corbusier’s concepts that man’s spirit and infinite modes of expression need to be made manifest, celebrated and encouraged.”

“The scale of the building is increased by emphasizing the top floor, which is supported on three-storey high columns. The intervening space is filled with volumes which reflect the needs of the interior. Thus the building reads from a great distance across the magnificent, rolling hills in which it is placed. Automobiles and townspeople enter from the lower level through the porte-cochere, which is focused on the gold dome of the church at the top of the hill. Students will arrive by a bridge from the top of the hill down to the roof, and from there into an exhibition area at the center. The building recognizes the broad expanses and distant views on one side, the inward looking hill aspect on the other, and the importance of the roofscape.”

“I like the building, and I feel good things about it.”

“The thing about the Dana Arts Center is that one can look at it from any angle and it always looks interesting. There is nothing on the outside that does not reflect something on the inside.”

“Dana as a building really faced significant challenges both as … maintenance and its usage. It’s being used as a museum when it really is not a good building for museums. In order to make that building a museum they blocked all the windows. All those walls [on the top floor] are windows. That whole building should be filled with light. You know how when you go upstairs and all those trays that stick out are offices? Those shouldn’t be offices, those should just be open to windows. And then the whole top floor should just be flooding that building with light. It is not, it is dark and scary, and you touch the walls and you bleed.

To renovate Dana, which is something I’m committed to doing, because mark my words we will one day love that building. It’s an interesting, beautiful building that’s been treated badly. And I also think it’s important to have it on this campus. Burke and Pinchin are beautiful and they fit right in, but that building should say something else.”

DRAWINGS - Design Drawings / Renderings

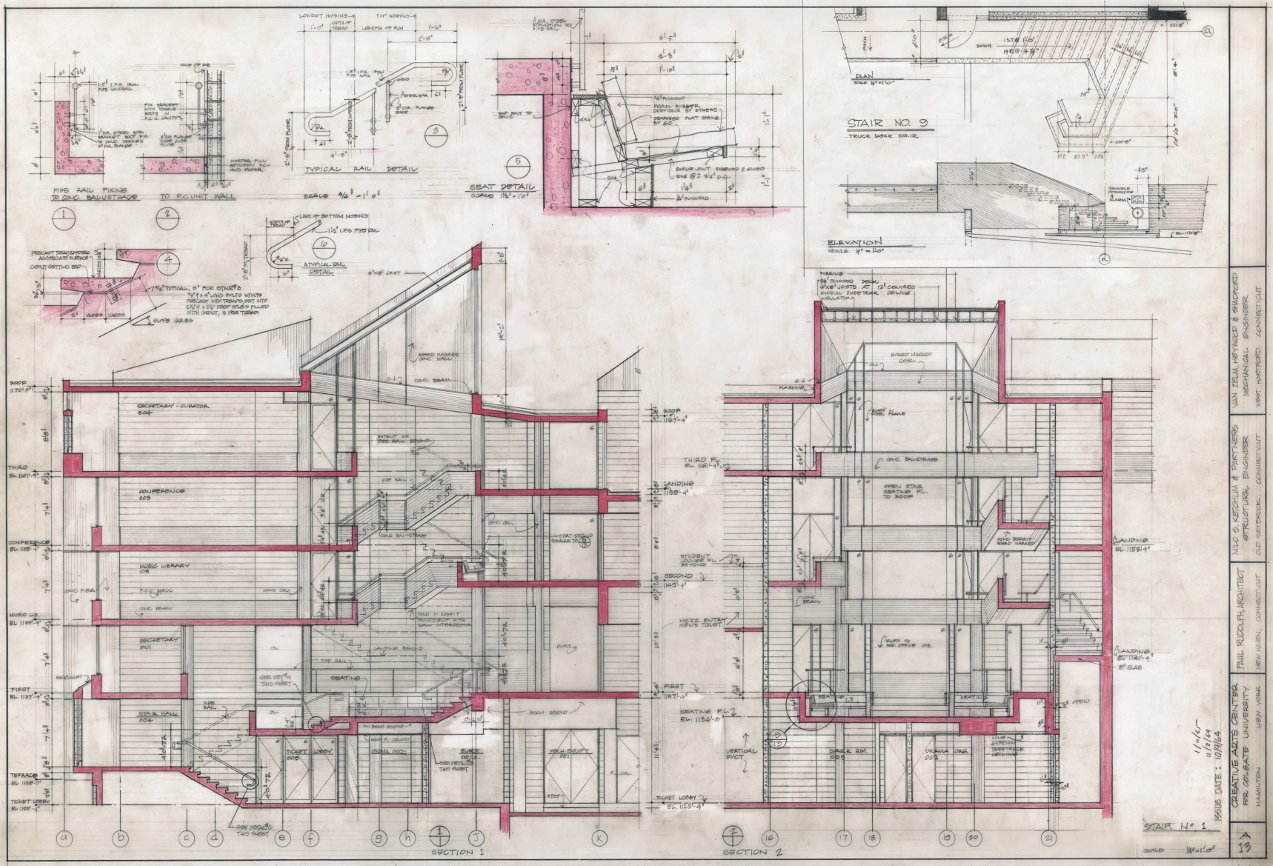

DRAWINGS - Construction Drawings

DRAWINGS - Shop Drawings

PHOTOS - Project Model

PHOTOS - During Construction

PHOTOS - Completed Project

PHOTOS - Current Conditions

LINKS FOR MORE INFORMATION

RELATED DOWNLOADS

PROJECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Art Center’s Design Lauded By President.” Syracuse Post Standard, April 11, 1964. p. 45

“Another art center by Rudolph unveiled.” il., plans, sec. Progressive Architecture 45 (May 1964): 57.

“Rudolph designs for Colgate.” il., plan, sec. Architectural Record 135 (May 1964): 10.

“Colgate Breaks Ground For Creative Arts Center.” Syracuse Standard Post, September 5, 1964. p. 51

“Preview: 73.” il., plan, sec. Architectural and Engineering News 8 (December 1964): 65-67.

“Project pour un theatre a Boston.” il., plan, sec. Architecture D’Aujourd’hui 35 (September-November 1965): 34.

“Colgate: creativity can’t be delegated.” il., plans. Progressive Architecture 46 (October 1965): 212.

“Unusual Rooftops.” Syracuse Herald Journal, February 15, 1966. p. 41

“Inside out.” il. Time 87 (11 March 1966): 72.

“Campus porte cochere.” il. Architectural Forum 124 (June 1966): 64.

“Colgate To Honor Architect.” Syracuse Post Standard, September 3, 1966. p. 51

“Colgate: creative arts center.” il., plans, sec. Progressive Architecture 48 (February 1967): 114-121.

“Colgate Exhibits Rudolph Concepts,” Syracuse Herald American, March 03, 1967. p. 40

“Implied spaces.” il., plan. Architectural Review 142 (September 1967): 171.

Charles A. Dana Creative Arts Center. Colgate University. Hamilton: Colgate University, n.d. il., plans. p. 10.

“Colgate University, Hamilton, N.Y.: creative arts center.” il., plan, sec. Architecture D’Aujourd’hui 39 (April 1968): 26-27.

“Everson at Expo '70.” Syracuse Post Standard, March 23, 1970. p. 8

Rudolph, P. and Moholy-Nagy, S. (1970). The Architecture of Paul Rudolph. New York: Praeger, pp. 167-173.

Paul Rudolph. Introduction and notes by Rupert Spade. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1971. il., plan, sec. plates 63-71. pp. 126-127.

Chermayeff, Ivan. Observation of American Architecture. New York: Viking, 1972. il. (pt. col.), pp. 68-69.

Kemper, Alfred M. Drawings by American Architects. New York: Wiley, 1973. sec. p. 489.

Paul Rudolph, Dessins D’Architecture. Fribourg: Office du Livre, 1974. il., sec, elev. pp. 136-139.

Tynan, Trudy. “Work of county center architect has leaky history.” Middletown Times Herald Record, September 06, 1974

“Chronological list of works by Paul Rudolph, 1946-1974.” il., plan. Architecture and Urbanism 49 (January 1975): 160.

“Creative arts center.” il., plan, sec. Architecture and Urbanism 80 (July 1977): 248-251.