Welcome to the Archives of The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture. The purpose of this online collection is to function as a tool for scholars, students, architects, preservationists, journalists and other interested parties. The archive consists of photographs, slides, articles and publications from Rudolph’s lifetime; physical drawings and models; personal photos and memorabilia; and contemporary photographs and articles.

Some of the materials are in the public domain, some are offered under Creative Commons, and some are owned by others, including the Paul Rudolph Estate. Please speak with a representative of The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture before using any drawings or photos in the Archives. In all cases, the researcher shall determine how to appropriately publish or otherwise distribute the materials found in this collection, while maintaining appropriate protection of the applicable intellectual property rights.

In his will, Paul Rudolph gave his Architectural Archives (including drawings, plans, renderings, blueprints, models and other materials prepared in connection with his professional practice of architecture) to the Library of Congress Trust Fund following his death in 1997. A Stipulation of Settlement, signed on June 6, 2001 between the Paul Rudolph Estate and the Library of Congress Trust Fund, resulted in the transfer of those items to the Library of Congress among the Architectural Archives, that the Library of Congress determined suitable for its collections. The intellectual property rights of items transferred to the Library of Congress are in the public domain. The usage of the Paul M. Rudolph Archive at the Library of Congress and any intellectual property rights are governed by the Library of Congress Rights and Permissions.

However, the Library of Congress has not received the entirety of the Paul Rudolph architectural works, and therefore ownership and intellectual property rights of any materials that were not selected by the Library of Congress may not be in the public domain and may belong to the Paul Rudolph Estate.

LOCATION

Address: 101 East 63rd Street

City: New York

State: New York

Zip Code: 10065

Nation: United States

STATUS

Type: Residence

Status: Built

TECHNICAL DATA

Date(s): 1966

Site Area: 2,512.5 ft² (233.4 m²)

Floor Area: 4 bed, 4.5 bath, 2,375 ft² (220.6 m²)

Height: 39’-0” (11.89 m)

Floors (Above Ground): 3

Building Cost:

PROFESSIONAL TEAM

Client: Alexander Hirsch; Halston

Architect: Paul Rudolph (1966-1967); Atmosphere Design Group (2019-)

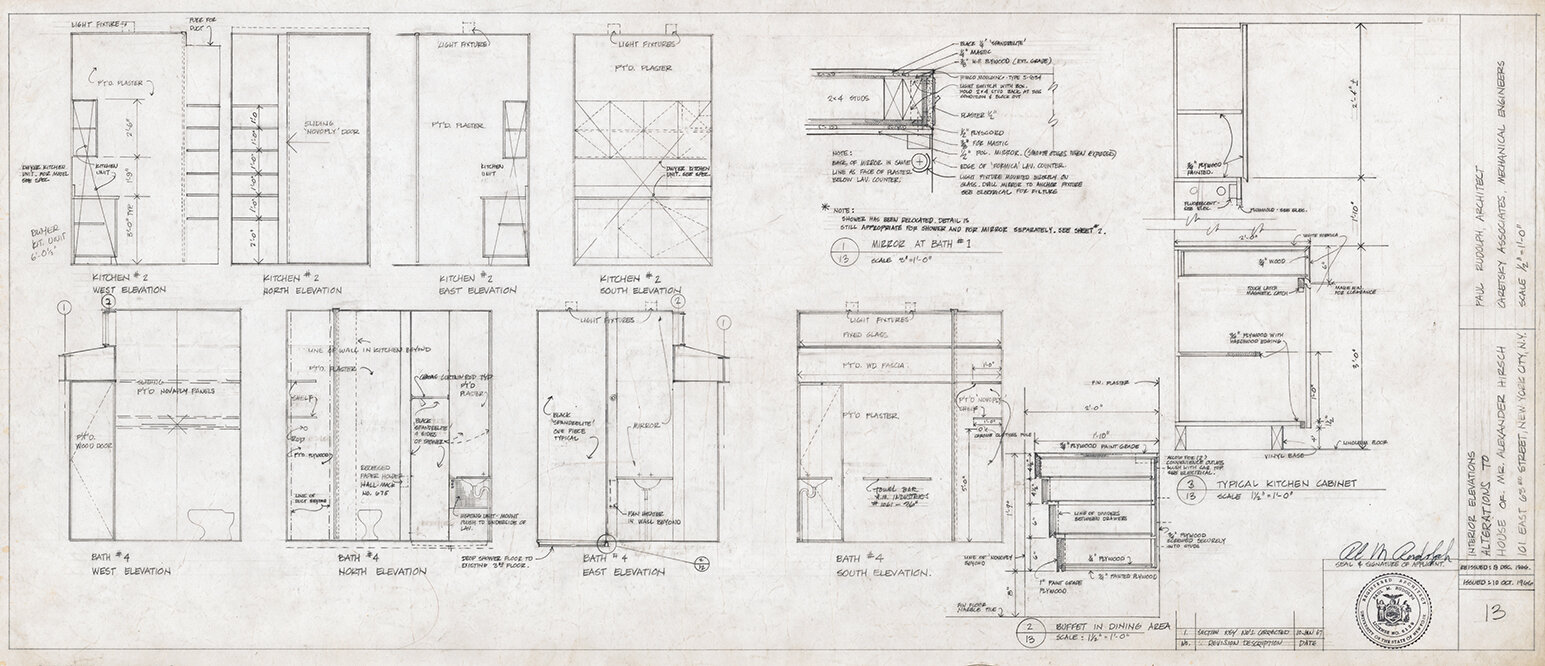

Rudolph Staff: Der Scutt, Senior Project Architect; John Pearce, Construction Administration;

Associate Architect:

Landscape:

Structural:

MEP: Caretsky, Mechanical Engineers (1966-1967); E4P Consulting Engineering PLLC (2019-)

QS/PM:

SUPPLIERS

Contractor: Blitman Corporation; Shawmut Woodworking & Supply, Inc. (Interior Renovation - 2019-)

Subcontractor(s): Outsource Consultants (Expediting - 2019-);

Hirsch Residence

Situated between a Federal style church and a traditional apartment house, the project scope is to design a townhouse on the framework of a 1880’s carriage house.

The original building on the site was designed and built in 1881 as a stable with residential quarters by architect Cornelius O’Reilly for Michael J. O’Reilly. From 1895 to 1961 it was owned by Edward J. Berwind (1848-1936) and family. Edward J. Berwind was a multi-millionaire financier and chairman of the Berwind-White Coal Mining Company of Philadelphia.

Alexander Hirsch (a lawyer and real estate investor who built a number of apartment houses in New York City) and Lewis Turner buy the existing building on January 24, 1966. Mr. Hirsch pays about $160,000 for the original carriage house property.

Mr. Hirsch hires Rudolph to design the home as a city residence for himself, already having a country home in East Hampton, Long Island.

Rudolph’s design removes the existing carriage down to the foundation. He removes an existing coal bin located at the back of the existing building and designs a glass-enclosed greenhouse in its place.

The new design’s street façade consists of a composition of steel and dark glass in a tripartite horizontal configuration: a solid base mostly made up of a solid garage door and entrance, a layered middle portion, and a projecting upper floor acting as a traditional cornice. Past the front door is a narrow hall with white walls and a slate floor which leads to the back of the house where the space opens up to a sunken living room: a three-story space looking out onto a three-story greenhouse, surrounded by a spiraling arrangement of balconies, open stairs and platforms. The main kitchen is located off a raised portion of the living room which is used as the dining room. On the second floor, a double-height Master bedroom with adjoining walk-in closet is located at the street side, which leads past a master bath and connects to a balcony that overlooks the living room below. On the mezzanine floor above, Rudolph locates a second bedroom and adds a bridge, without a guardrail and open to the living room, to a third bedroom with bath at the back of the house. On the third floor is a bedroom, living room and small kitchen with teak floors and exposed brick walls which can function as a separate apartment. This level opens out onto a roof deck.

Construction drawings are issued on October 10, 1966.

Revised construction drawings are issued on December 19, 1966.

Construction is completed on December 11, 1967.

A Certificate of Occupancy is issued on December 29, 1967.

On July 16, 1969 the home is photographed by Ezra Stoller.

On March 06, 1974, the house is purchased by fashion designer Roy Halston Frowick, better known as Halston, who moves in and nicknames it the “101” after its street number.

Halston renovates the new home and brings Rudolph in as the architect. The bookcase and sculptures at the mezzanine are removed. The greenhouse was deemed too lush and reworked by Robert Laster into a simple bamboo forest. Artwork on the walls around the residence was reduced to a minimum. Andy Warhol hangs a blank canvas and signed the lower right section of the wall behind the canvas on commission by Halston, who was livid when he returned from a weekend at Montauk to see a blank canvas.

Halston fills the house with dozens of votive candles so that minimal artificial light is needed after the sun goes down.

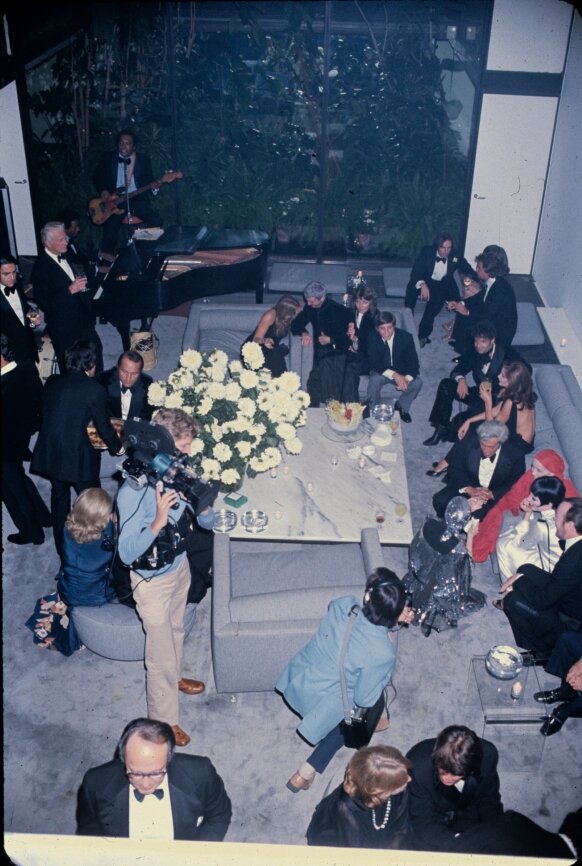

The house becomes an infamous party hangout for Halston and his celebrity friends such as Andy Warhol, Truman Capote, Bianca Jagger, Liza Minnelli, Elizabeth Taylor, Lauren Bacall, Anjelica Huston and Diana Vreeland. A party at ‘101’ became known in the vernacular of the time as a “Halston Happening.” Liza Minnelli and Bianca Jagger were both off and on residents of the top-floor suite.

Halston retires from the public eye in 1984, and the house becomes a contained and quiet sanctuary

On January 04, 1990 Halston sells the house complete with furnishings for $5,000,000 USD to the ‘Cryden Corporation’ which is composed of German celebrity photographer Gunter Sachs and Fiat's Gianni Agnelli.

Sachs, a modern art collector with a collection of Andy Warhol’s artwork, lines the walls with his own private collection of celebrity candid photos. He also makes several changes to the interiors. He removes the carpeting throughout the living room and on the raised platforms and open stairs, replacing it with strip wood flooring. He also removes the floating desk at the first floor balcony overlooking the living room, replacing it with a shoe-less glass guardrail. At the floating stairs he removes the plexiglas tubes which Rudolph had installed as a handrail. On the mezzanine level, famous for its dangerous bridge, he installs glass guardrails throughout.

On May 07, 2011 Gunter Sachs passes away.

On November 03, 2011 the home is listed for sale for $38,500,000 USD by Noble Black, Carmen Marques Perez and Bonnie Pfeifer Evans of the Corcoran Group.

Gunter Sachs’ art collection on display in the home is removed and auctioned by Sotheby’s in May, 2012.

On December 16, 2012 the listing is removed by the Corcoran Group.

On March 19, 2015 the home is listed for sale for $40,000,000 USD by Howard Morrel & Leslie Hirsch of Engel & Völkers New York Real Estate.

On March 20, 2015 the listing is removed by Engel & Völkers New York Real Estate.

In April 2016 the property is the subject of its own website (www.101e63.com) created by Engel & Volkers New York Real Estate. The site is disabled in September 2019.

On April 06, 2016 the home is listed for $28,000,000 USD by Engel & Völkers New York Real Estate.

On January 06, 2017 the listing priced is changed to $24,350,000 USD.

On February 02, 2017 the listing price is revised to $28,000,000 USD.

On January 09, 2018 the listing price is reduced to $24,000,000 USD.

On January 15, 2019 the home is purchased from the Cryden Corporation by the ‘101 East 63rd Street NYC LLC’ on behalf of Tom Ford for $18,000,000 USD.

On August 19, 2019 construction drawings are filed by Atmosphere Design Group to do interior renovations including ‘demolition and installation of partitions, ceiling, door modifications and exterior façade restoration.’ No change in use, egress or occupancy is proposed. The cost of the renovations is estimated to be $750,000 USD.

On September 06, 2019 a construction permit is issued.

On December 09, 2019 the New York Times Style Magazine lists the Halston interior as #19 on its ‘25 Rooms that Influence the Way We Design’

The house appears in the Netflix series ‘Halston,’ based on the biography Simply Halston, published in 1991 by American author Steven Gaines. After visiting the Paul Rudolph Institute’s Modulightor building to discuss the project, Netflix location scouts visit the original home but find it unusable due to the ongoing construction work. They alert the Paul Rudolph Institute that ‘the space is gutted - its unrecognizable’ and rebuild parts of the house’s interior in a home located in Brooklyn’s Red Hook neighborhood.

“A world of its own, inward looking and secretive, is created in a relatively small volume of space in the middle of New York City. Varying intensities of light are juxtaposed and related to structures within structures. Simple materials (plaster, paint) are used, but the feeling is of great luxuriousness because of the space. The one exposed facade reveals the interior arrangement of volumes by offsetting each floor and room in plan and section.”

“Technically, this is the remodeling of a carriage house, but Rudolph’s renovation was so total that it is, for all practical purposes, a new building. The interior is a set of complex spaces marked by a skillful balance of floating planes, stairways, balconies, platforms, and windows, and the façade hints as it should at the drama within. It is a subtle composition of steel and dark glass, with a gently projecting upper floor as cornice-like horizontal element, a strong vertical center, and a solid base. The façade reflects interior functions perfectly, yet it works equally well as a composition in its own right. It is strong, yet always restrained, which permits it to blend gracefully into its older surroundings; rarely has any New York building front managed to make so powerful a statement of its own and yet achieve such quiet urbanity at the same time.”

“I’m Halston and this is my home. The architect was Paul Rudolph and the day I saw it, I bought it. Its the only real modern house built in the city of New York since the second world war. Its like living in a three dimensional sculpture.”

“I’m going to enjoy making money for you Halston because you know how to spend it.”

“At first you want to change everything when you move into a house like this. But the house is such a work of art you end up giving into it.”

“I know this house was designed for somebody else, but I really feel as though it was built for me.”

“I like white and sparse. I wanted to take out some things that were just decorative.”

“Halston’s house is spare, but totally luxurious. Standing inside it, one cannot help but think of Halston’s own designs, since the ideas which underlie the architecture parallel the designers own themes: simple elements arranged in perfect composition, with the feeling of lushness coming not from excess activity, but from elegant materials and a superb sense of balance.”

“I thought when I bought the house I would spend all my time in the other rooms and only use the big one for company, but I find it really works for me. I sit here and sketch and watch the light constantly change.”

“This is the way I wish my house looked. It looked so rich at Halston’s, so many orchids, so cool…”

“The house was like no other in New York. It was one of only a handful of private houses that had been built in Manhattan after World War II. It was this chocolate exterior, some heavy-duty plastic and you walked in this narrow hallway which he had lined at one point with Andy’s little Maos. Then you were in this huge, triple height living room that went right to the back of the house where you had just a narrow strip of garden which was all just bamboo trees. It was maybe about six feet deep at most. It wasn’t a garden you sat in, it was just a glass wall, then you’d see the bamboo shoots.

All the furniture was built in. It was gray flannel banquettes, big sort of square, geometric black coffee tables. There was a built-in fireplace on the left wall with a slab for a mantlepiece. There was a staircase with no bannister, the steps were floating. I remember the night Diana Vreeland was walking up that staircase we were so terrified she would topple over. That led you to this mezzanine balcony which was sort of over the kitchen, that was all on the street end of the house and there were bedrooms up there.

The balcony was very dramatic. It had a slab of a built-in bench. It didn’t have any railing or anything. I have a photograph I took of Pat Cleveland and Sterling St. Jacques wearing rabbit ears and dancing on that balcony. It was perfect for performances. It was a very dramatic house that was really meant for entertaining. It was kind of this high style minimalism. It was unique.”

DRAWINGS - Design Drawings / Renderings

DRAWINGS - Construction Drawings

DRAWINGS - Shop Drawings

PHOTOS - Project Model

PHOTOS - During Construction

PHOTOS - Completed Project

PHOTOS - Current Conditions

LINKS FOR MORE INFORMATION

RELATED DOWNLOADS

PROJECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adrienne Gaffney. “Glamour, Mayhem, and Baked Potatoes: What It Was Like to Party at Halston’s.” Town & Country, 22 May 2021.

Alexandra Alexa. “Legendary Designer Halston’s Former UES House and Famed Party Spot Is off the Market after Four Years.” 6sqft, 22 Jan. 2019.

Alistair Walsh. Playboy Gunter Sachs’ Former New York Home on the Market | Urban. 6 Dec. 2011.

“Article on Planned Conversion by Architect . Rudolph of Run-down Carriage House.” New York Times, 10 Feb. 1967.

Cathy Whitlock. “The Heady, Hazy, Hedonistic Days of Halston Get the Ryan Murphy Treatment.” Architectural Digest, 14 May 2021.

Chermayeff, Ivan. Observations on American Architecture. Viking, 1972.

“Chronological List of Works by Paul Rudolph, 1946-1974.” Architecture and Urbanism, no. 49, Jan. 1975.

Decca Muldowney. “Lenox Hill Townhouse Where Andy Warhol Partied Sells for $18M.” The Real Deal New York, 24 Jan. 2019.

Emma Specter and Jared Ellner. “Tom Ford Just Bought Halston’s Famed Upper East Side House.” Garage, 22 May 2019.

Fred A. Bernstein. “Paul Rudolph’s Legacy Lives on Through His Outstanding Buildings.” Galerie, 15 Oct. 2018.

Futagawa, Yukio. Global Interior: Houses in U.S.A., #1. A.D.A Edita, 1971.

Giuliana Matarrese. “The Mini TV Series on Halston, the Missed Opportunity to Tell the Greatest American Couturier.” Marie Claire, 17 May 2021.

Haley Chouinard. “Manhattan’s Famed Halston House Sells for $18 Million.” Galerie, 28 Jan. 2019.

Herbert Smith. 25 Years of Record Houses. McGraw-Hill, 1981.

“Hirsch Residence.” Architecture and Urbanism, no. 80, July 1977, pp. 64–65.

Iconic “Urban Retreat” in New York City by Paul Rudolph. 12 Jan. 2012.

Ingrid Abramovitch. “7 Surprising Ways Halston Changed Interior Design Forever, According to the Director of the Hot New Netflix Series.” Elle Decor, 21 May 2021.

Jacqueline Navas and Eman Alami. “How Accurate Were the Settings and Faces of Netflix’s ‘Halston?’” CR Fashion Book, 18 May 2021.

Josh Barbanel. “Jet-Setting to a Time Past.” The Wall Street Journal, 3 Nov. 2011.

Kathryn Hopkins. “Did Tom Ford Just Buy Halston’s Former Party House?” Women’s Wear Daily, 19 Mar. 2019.

Lesley Frowick. Halston: Inventing American Fashion. Rizzoli, 2014.

Lilah Ramzi. “Halston: An Essential Guide to Living in Style.” Vogue, 17 May 2021.

Mark David. “Gunter Sach’s Estate To Unload A Rare Paul Rudolph Residence in New York City.” Variety, 5 Jan. 2012.

Mary Elizabeth Andriotis. “How Halston’s Manhattan Townhouse Was Recreated for Netflix’s New Miniseries About the Designer.” House Beautiful, 20 May 2021.

Paul Goldberger. The City Observed: New York. Random House, 1979.

Paul Rudolph. Paul Rudolph: Dessins D’Architecture. Office du Livre, 1974.

Paul Rudolph and Sybil Moholy-Nagy. The Architecture of Paul Rudolph. Praeger, 1970.

Ray Faulkner and Sarah Faulkner. Inside Today’s Home. Fourth, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1975.

Redação. “See Inside Halston’s $18 Million Home.” L’Officiel, 26 May 2021.

Richard D. Lyons. “Halston Town House Sold.” The New York Times, 21 Jan. 1990, p. 255.

Santiago Villaseñor. “The House Where Halston Was Partying Now Belongs to Tom Ford.” Elle, 26 May 2021.

Shinan Govani. “Designs of the Times as Halston’s Disco Ball Glitters in New Netflix Series.” The Hamilton Spectator, 30 Apr. 2021.

Smith, Herbert. “Record Houses of 1970.” Architectural Record, no. 147, May 1970, pp. 42–45.

“The History of Halston’s New York Townhouse.” Women’s Wear Daily, 24 May 2021.

Thomas W. Ennis. “Paul Rudolph Plans Modern House Here On Frame of 1870’s; Paul Rudolph Plans Modern House on a 90-Year-Old Frame.” The New York Times, 19 Feb. 1967. NYTimes.com.

“Total Townhouse.” House and Garden, no. 136, Nov. 1969, pp. 122–27.

White, Norval. AIA Guide to New York City. Macmillan, 1978.