Welcome to the Archives of The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture. The purpose of this online collection is to function as a tool for scholars, students, architects, preservationists, journalists and other interested parties. The archive consists of photographs, slides, articles and publications from Rudolph’s lifetime; physical drawings and models; personal photos and memorabilia; and contemporary photographs and articles.

Some of the materials are in the public domain, some are offered under Creative Commons, and some are owned by others, including the Paul Rudolph Estate. Please speak with a representative of The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture before using any drawings or photos in the Archives. In all cases, the researcher shall determine how to appropriately publish or otherwise distribute the materials found in this collection, while maintaining appropriate protection of the applicable intellectual property rights.

In his will, Paul Rudolph gave his Architectural Archives (including drawings, plans, renderings, blueprints, models and other materials prepared in connection with his professional practice of architecture) to the Library of Congress Trust Fund following his death in 1997. A Stipulation of Settlement, signed on June 6, 2001 between the Paul Rudolph Estate and the Library of Congress Trust Fund, resulted in the transfer of those items to the Library of Congress among the Architectural Archives, that the Library of Congress determined suitable for its collections. The intellectual property rights of items transferred to the Library of Congress are in the public domain. The usage of the Paul M. Rudolph Archive at the Library of Congress and any intellectual property rights are governed by the Library of Congress Rights and Permissions.

However, the Library of Congress has not received the entirety of the Paul Rudolph architectural works, and therefore ownership and intellectual property rights of any materials that were not selected by the Library of Congress may not be in the public domain and may belong to the Paul Rudolph Estate.

LOCATION

Address: 3030 East Cornwallis Road

City: Durham

State: North Carolina

Zip Code: 27713

Nation: United States

STATUS

Type: Office

Status: Built; Partially Demolished

TECHNICAL DATA

Date(s): 1969-1972

Site Area:

Floor Area: 312,303 s.f.

Height: 74.62 ft.

Floors (Above Ground): 5

Building Cost: $10,000,000 USD

PROFESSIONAL TEAM

Client: Burroughs Wellcome & Company, Inc.

Architect: Paul Rudolph

Associate Architect:

Landscape:

Structural: Lockwood-Greene Engineers, Inc.

MEP: Lockwood-Greene Engineers, Inc.

Site: Lockwood-Greene Engineers, Inc.

QS/PM:

SUPPLIERS

Contractor: Daniel Construction Company, Inc. a division of Daniel International Corporation

Subcontractor(s): Southern Elevator Company (Elevators); Peden Steel Company (Steel fabricator and erector);

Burroughs-Wellcome Company (USA) Corporate Headquarters

In February 1969, pharmaceutical company Burroughs Wellcome purchases a little over 66 acres of rolling woodland from the Research Triangle Foundation to relocate its headquarters from Tuckahoe, New York. The company is a subsidiary of The Wellcome Foundation Ltd. of London, England.

The client requests a building design that will be shaped to its needs, yet remain architecturally distinctive.

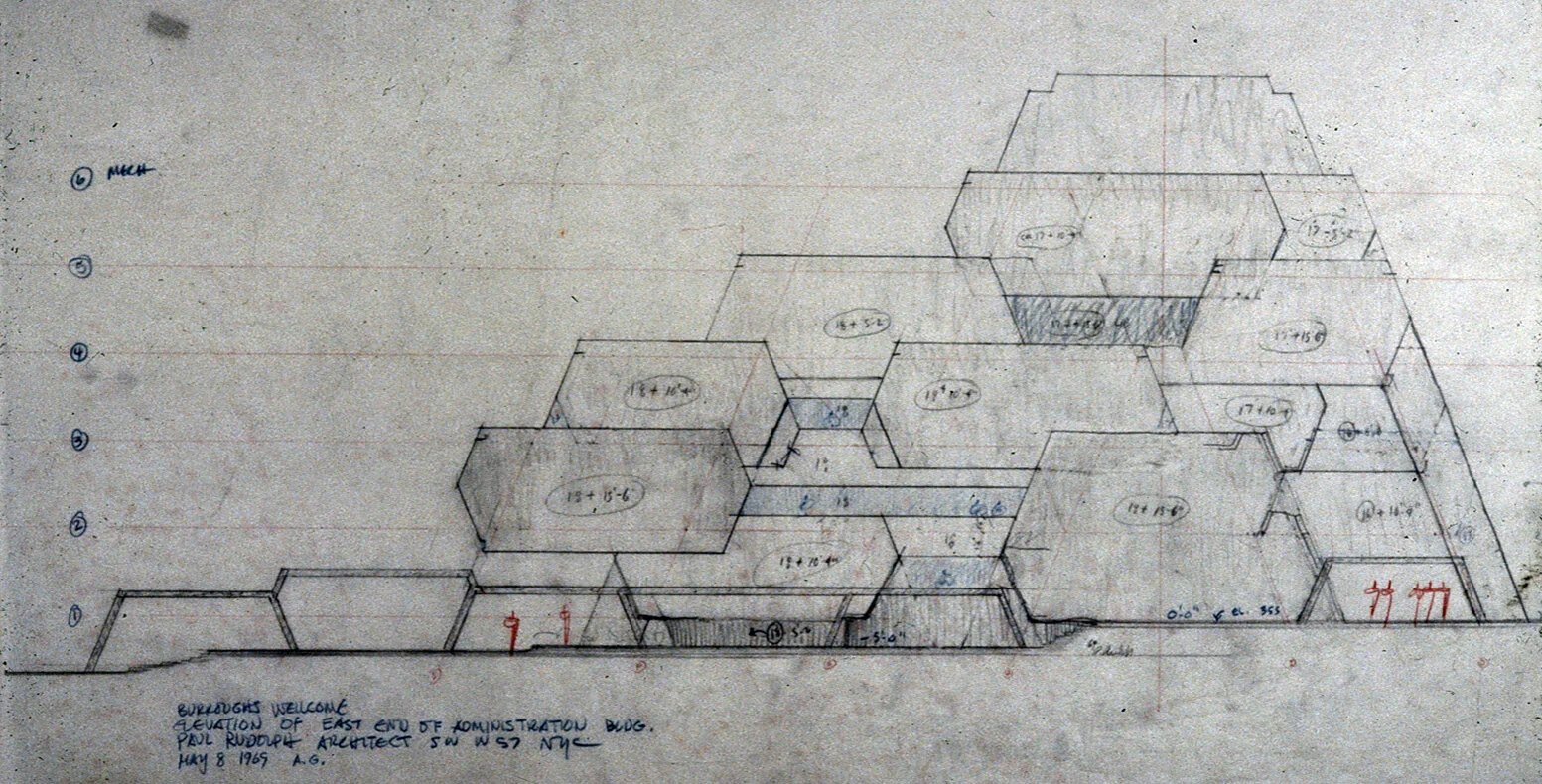

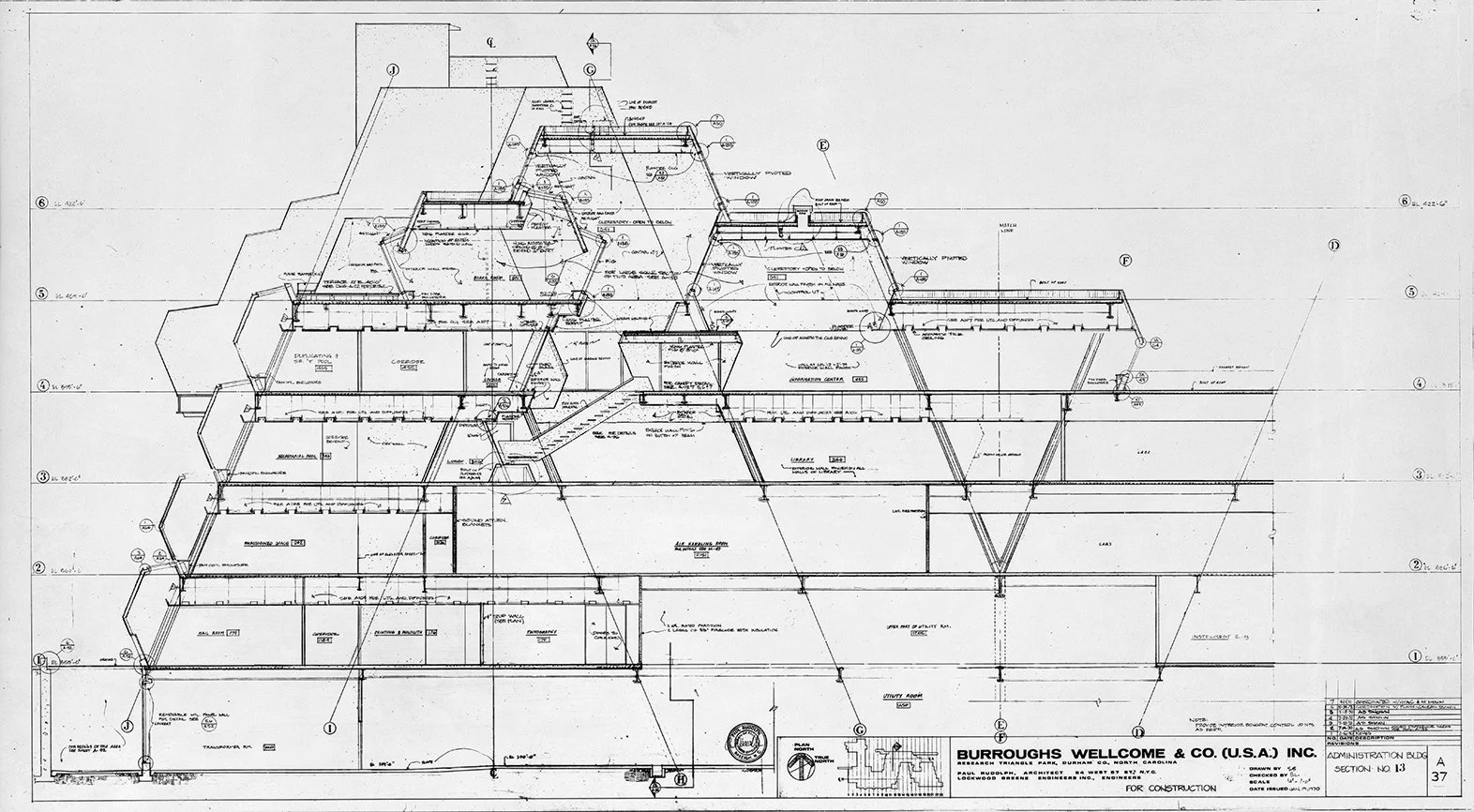

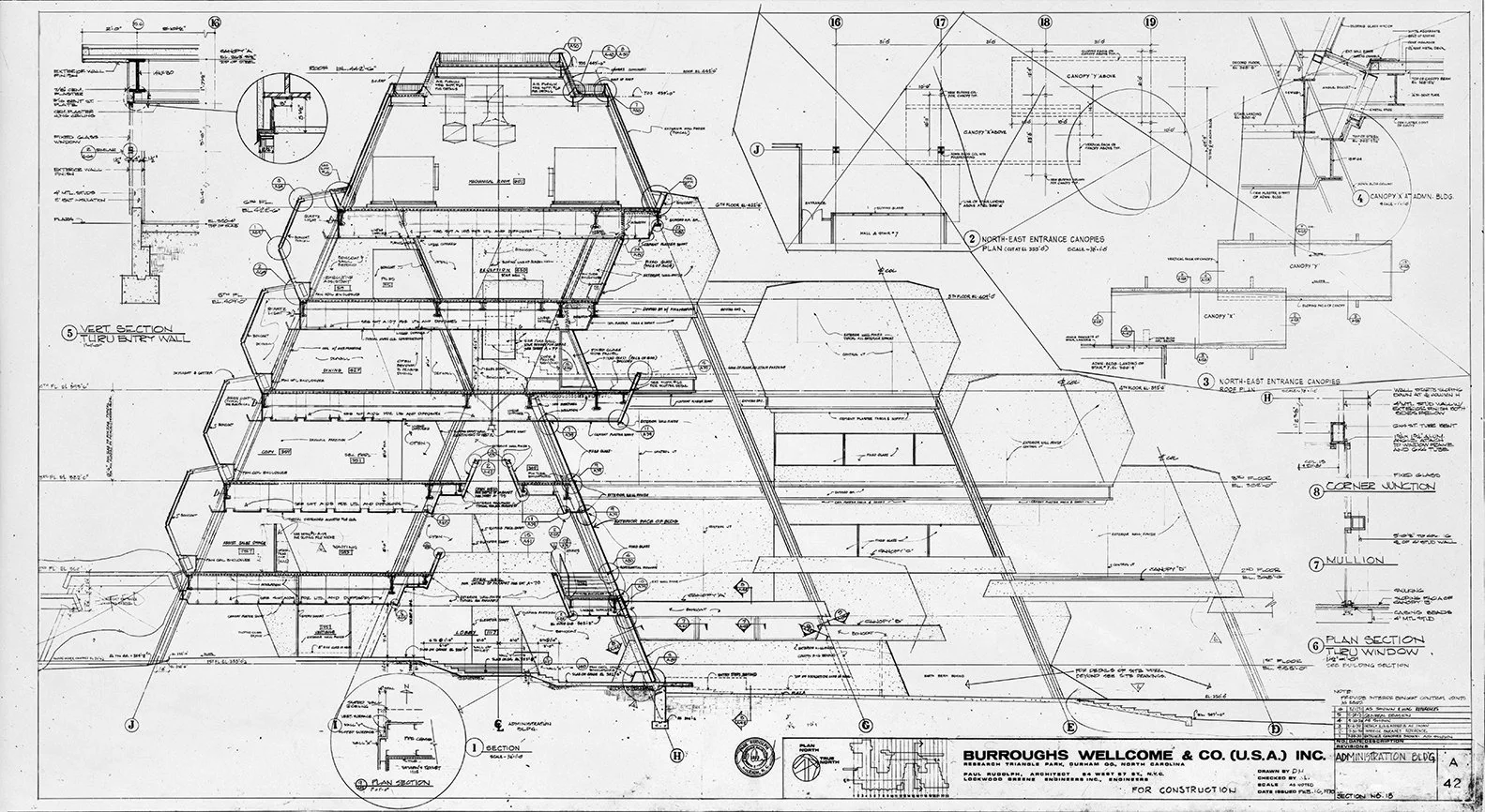

Flexibility is a primary programmatic goal for the design. Each major area in Rudolph’s plan - laboratories, administration and support services - are capable of being expanded by simple, linear addition. To prepare for this, Rudolph leaves the expansible ends of the building expressed in a random pattern of flattened hexagons, so that any of the elements can be extended horizontally without disturbing the building’s visual order.

The building program includes 312,303 s.f. of research laboratory and administrative space including 140 labs, a library, auditorium, cafeteria and support activity spaces for 400 workers.

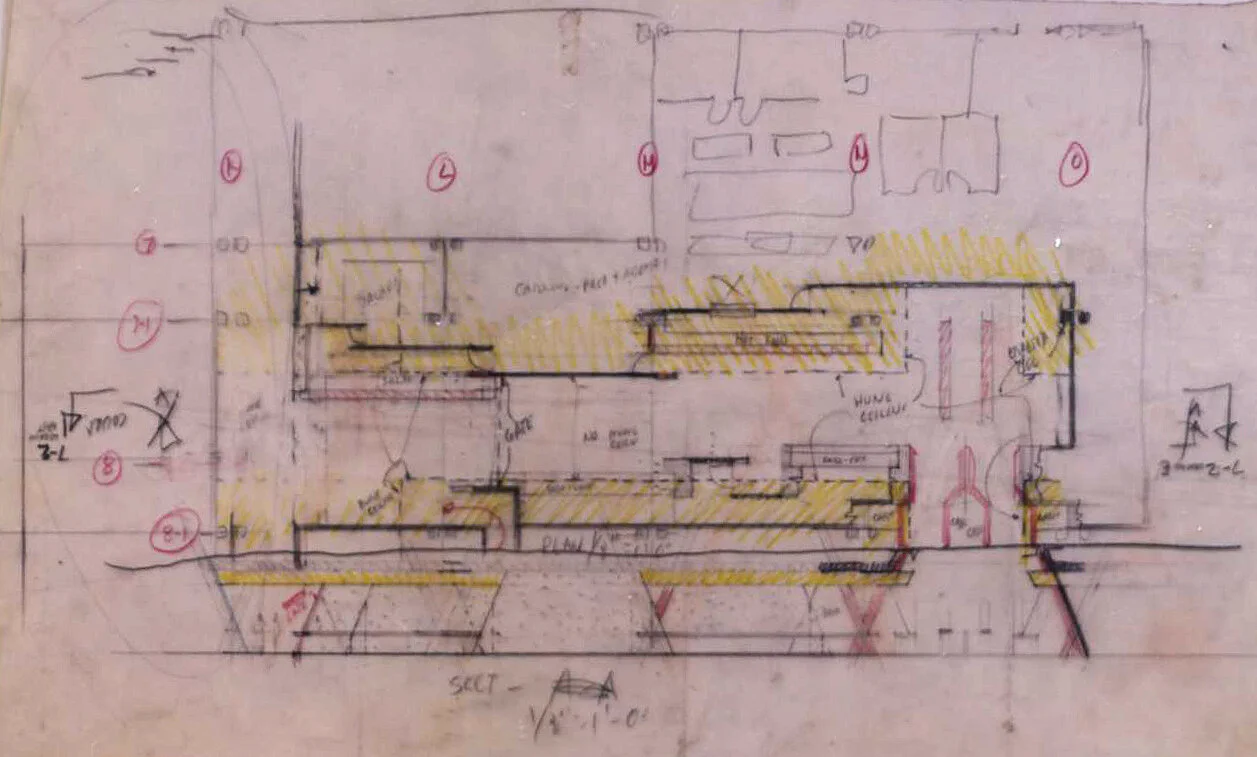

In plan, the building forms a giant ‘S’ with opposing arms that form a main entry court and large service yard. Reception, cafeteria, library, auditorium and administrative offices flank the entry court. Laboratories, research offices and test animal quarters surround the service yard.

The building exterior and partial interior is finished in using a limestone aggregate which is sprayed in place to a plastic binder. Rudolph used the same textured finish at the Deane Residence and the 1972 Micheels Residence.

The building features 140,000 sf of exposed aggregate finish exterior walls and 90,000 sf of exposed aggregate finish interior walls. Rudolph estimates the finish required 20,000,000 stones to complete.

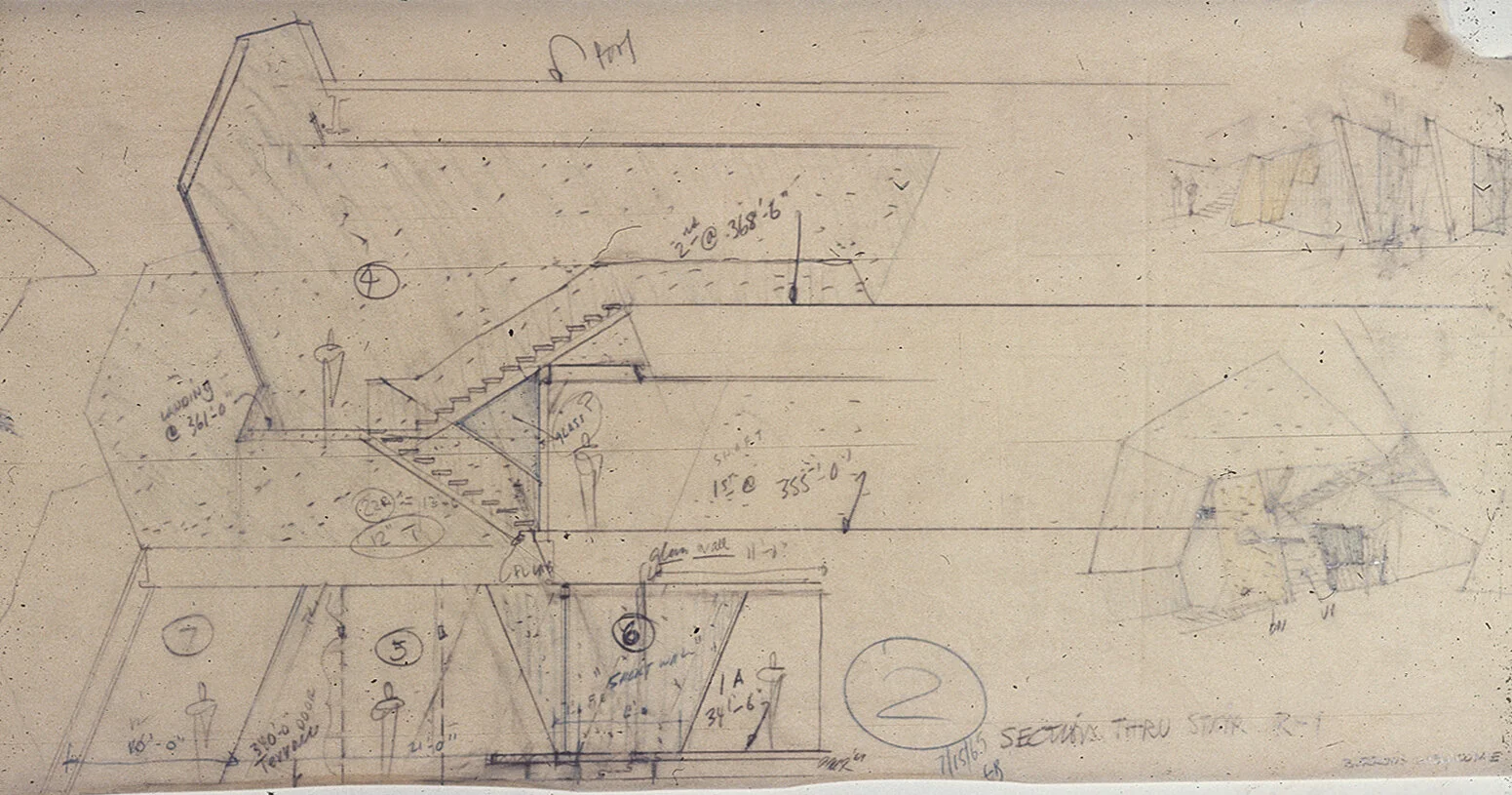

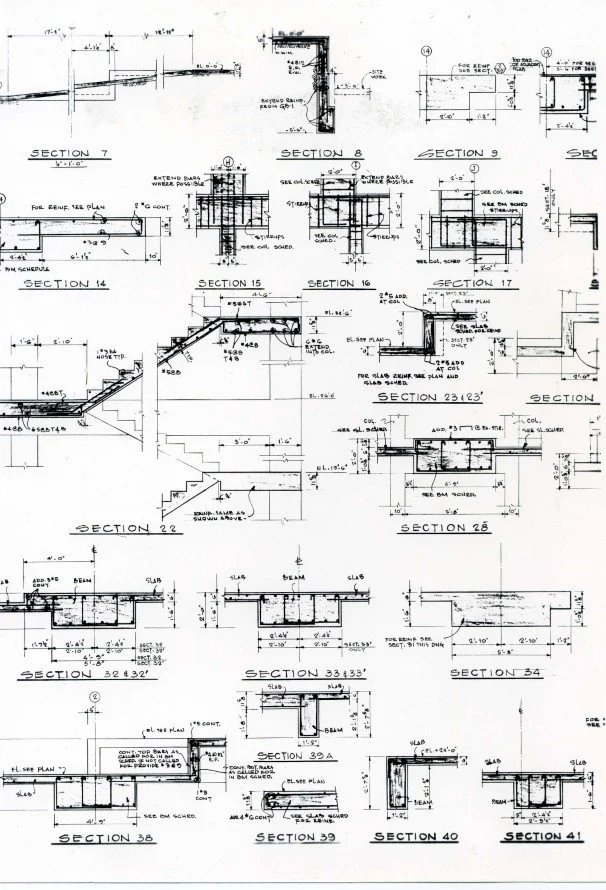

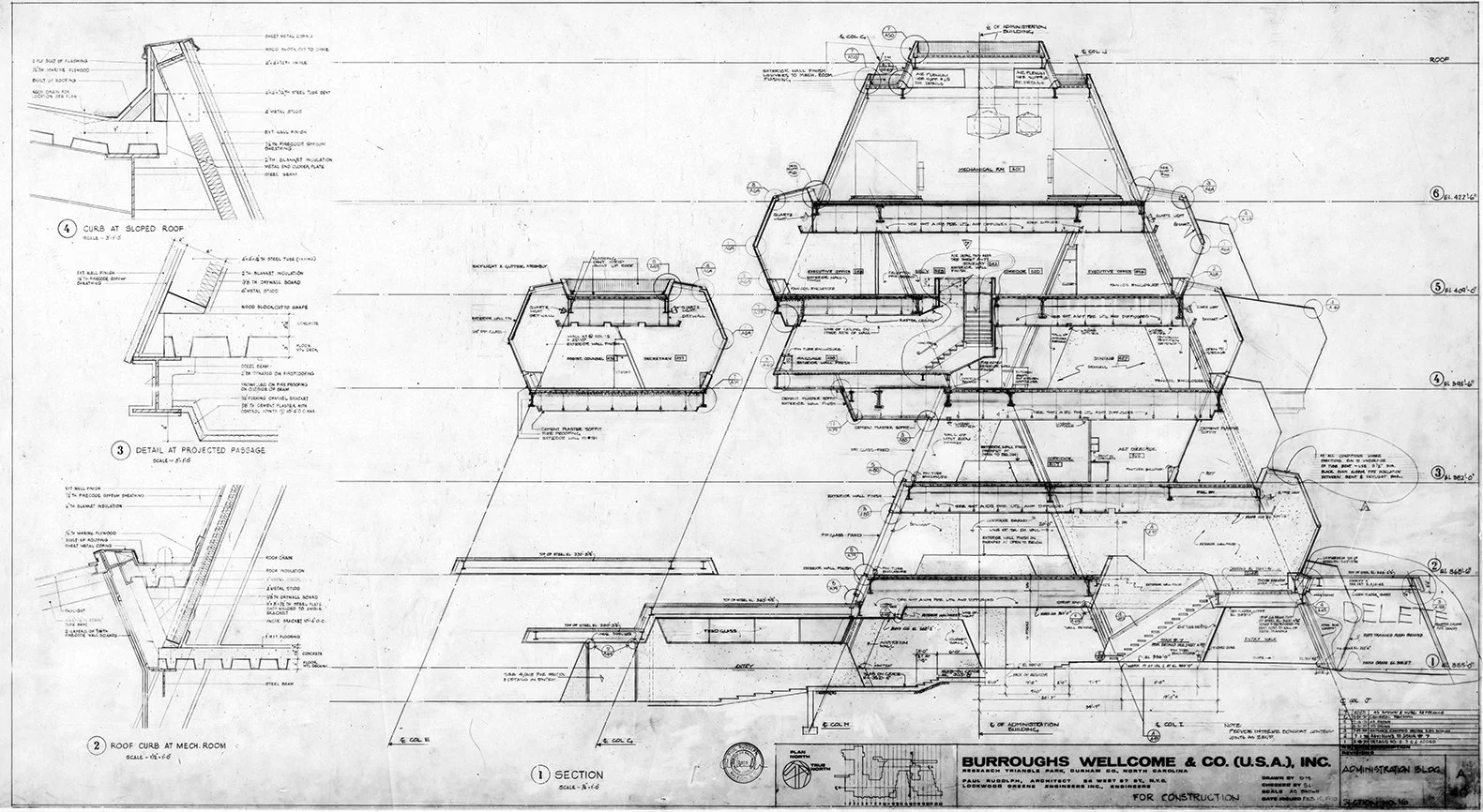

The building structure is an eccentrically loaded trapezoidal steel frame with columns inclined at 22.5 degrees. The original slant of the building’s structural system changes during the course of design at the request of the project’s structural engineer. The angle is designed on a 22.5-degree slant since the ridge that the building sits on is at the same incline. To absorb the substantial bending moments, floor beams and columns are linked in the transverse direction by rigid moment connections. Tie beams, below grade, take up the horizontal component of all gravity loads.

Bethlehem Steel supplies 3,100 tons of ASTM A-36 structural steel for the building’s structural framing.

The building is dedicated on Friday, April 7th 1972. A collectors medallion is issued to celebrate the dedication which features a rendering of the building on one side, and a unicorn (the company’s logo) on the other side. The dedication ceremony is attended by Lord Franks, chairman of the Wellcome Trust, the registered charity which owns the British-based worldwide pharmaceutical company.

Rudolph gives a walking tour of the building as part of the dedication ceremony. He writes a description of the building for the tour saying, “the building is conceived as a man-made extension of the ridge upon which it is built. The building is terraced, each floor being smaller that the one below it. Its placement allows people to enter from below walking through a courtyard and porch into the lobby.”

In May, 1972 a lawsuit is filed by the Burroughs Wellcome Company seeking $1.5 million USD for damages for what it contends is “faulty and defective” construction work on the building. The suit is filed in the U.S. Eastern District Court against general contractor Daniel Construction Company of Greenville, SC; exterior subcontractor William A. Duiguid Company of Arlington Heights, Illinois; and M. and O. Exterprises Inc. of Springfield, Missouri which supplied the exterior finish, and Paul Rudolph as designer. The company contends the finish used on the outside of the structure is damaging the building’s exterior.

The building interior and exterior are used as part of the set for the 1983 science fiction film Brainstorm starring Christopher Walken and Natalie Wood.

The building is originally known as the Burroughs-Wellcome Company Headquarters and later the GlaxoSmithKline Building.

The original building has several additions, including a Main Building addition in 1976, a Toxicology/Experimental Pathology Building addition in 1978 and a South Building Expansion in 1982. Rudolph also was asked to create a new Masterplan for the site in 1982.

The building is closed to the public for decades as pharmaceutical companies Glaxo, Glaxo Wellcome, and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) actively use it as office and laboratory space. Employees are not permitted to take cameras into the facility to take photos of it due to the sensitivity of the research being conducted.

The building is renamed the Elion-Hitchings Building in 1988, honoring Gertrude Elion and George Hitchings - research chemists with Burroughs Wellcome who shared the 1988 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Sir James Black.

On April 21, 1989 four ACT UP members use steel plates and rivets to barricade themselves inside an office in the building. They demand a cut in the price of AZT, still the most expensive medicine in history at $8,000 for a year's dosage.

In 1995, Burroughs Wellcome and Glaxo merge to become Glaxo Wellcome and a merger between that company and SmithKline Beecham establishes the company as GlaxoSmithKline. The company’s operations are then relocated another facility.

In February 2010 the building is listed for sale.

On June 30 2012, Glaxo sells its iconic Elion-Hitchings Building, two interconnected office buildings and 140 acres of land for $17.5 million to United Therapeutics.

On October 20 2012, the building is open for a public tour arranged by Triangle Modernist Houses (now known as USModernist) with United Therapeutics. A video of the event can be watched here.

United Therapeutics demolishes part of the structure in 2014.

On September 04, 2020 United Therapeutics is issued a demolition permit for the building from the City of Durham. Clear Site Industrial, LLC is listed as the demolition contractor.

“This building is an exciting and ingenious combination of forms [in which] one discovers new and different qualities of forms and spaces . . . a splendid climate for scientific scholarship and for the exchange of ideas.”

“This complex climbs up and down a beautiful ridge in the green hills of North Carolina and is architecturally an extension of its site. An “A frame” allows the greatest volume to be housed on the lower floors and yet connected to the smaller mechanical system at the apex of the building. The diagonal movement of interior space opens up magnificent opportunities. Anticipation of growth and change is implicit in the concept.”

“A dynamic and expressive design was created for this administrative headquarters. Rhythm and space are achieved through the use of strong external forms arranged in a contemporary “ziggarat fashion.” Lighting within the interior spaces effectively adds to the building’s design. The interaction of bold forms with the rolling hillside is intriguing as well as harmonious. The building is one of its kind in the nation.”

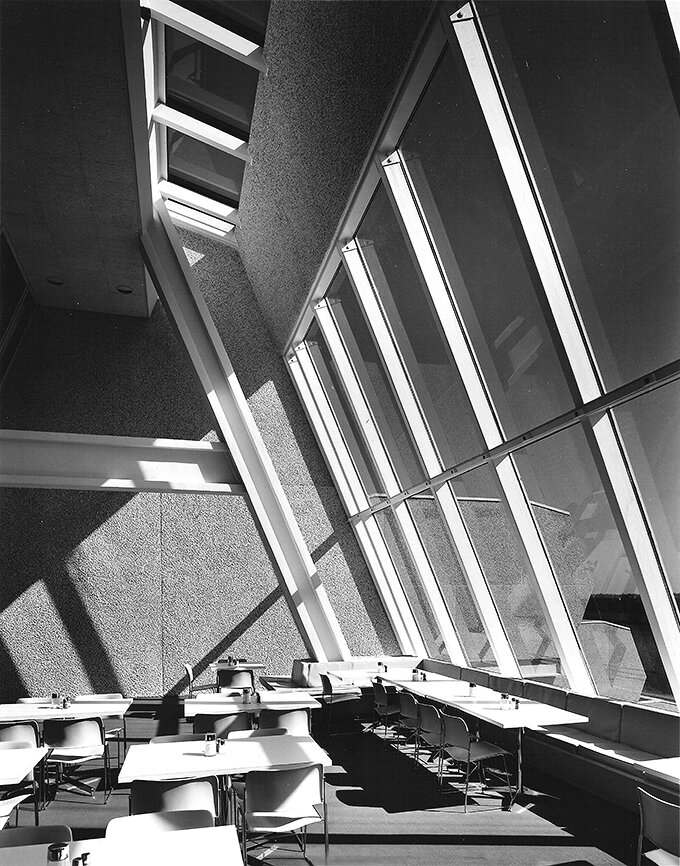

“From a spatial viewpoint, the interior is given a new dimension with its sloping walls, creating an impression not unlike a growing tree - angles, light and shadow, flexibility. The building imparts a sense of being a living organism, rather than a box-like form. The laboratories, well-lit, complete in all detail, will have an individuality and a uniqueness quite unlike other laboratories, because they have higher ceilings lit by skylights at each end.”

“The functions of the building are celebrated architecturally. There is an emphasis on those things that cannot be changed, such as mechanical shafts, and columns, and on the parts that can be changed; for example, the flexibility of the laboratories and other work areas. Permanent interior structural components will have the same finish as the building’s exterior; the flexible components will be finished in a variety of surfaces, especially the paneling and the painted drywall.”

“The building is conceived as a man-made extension of the ridge upon which it is built. The building is terraced, each floor being smaller that the one below it. Its placement allows people to enter from below walking through a courtyard and porch into the lobby.””

“The lobby is three stories high, with floors on several levels, following the contours of the hillside. In addition to its function as the building’s reception area, the lobby is the focal point of the building’s communications. Approximately three-fourths of the building’s offices are grouped around the multi-level lobby which will thereby be animated by constant use. This large central area will be the interior focal point of the building and will eliminate most corridors.”

“The building utilizes a truncated steel A-frame; that is the diagonal supporting members are linked at the roof of the building by a horizontal system of beams.”

“Many-faceted, like science itself, is this striking new building designed by the American architect Paul Rudolph to house the Wellcome Research Laboratories and the administration of Burroughs Wellcome Company in the Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA.

It was recently officially opened by Lord Franks, chairman of the Wellcome Trust, the registered charity which owns all of the shares of the British-based worldwide pharmaceutical enterprise which has companies in 28 countries, with group headquarters in London.”

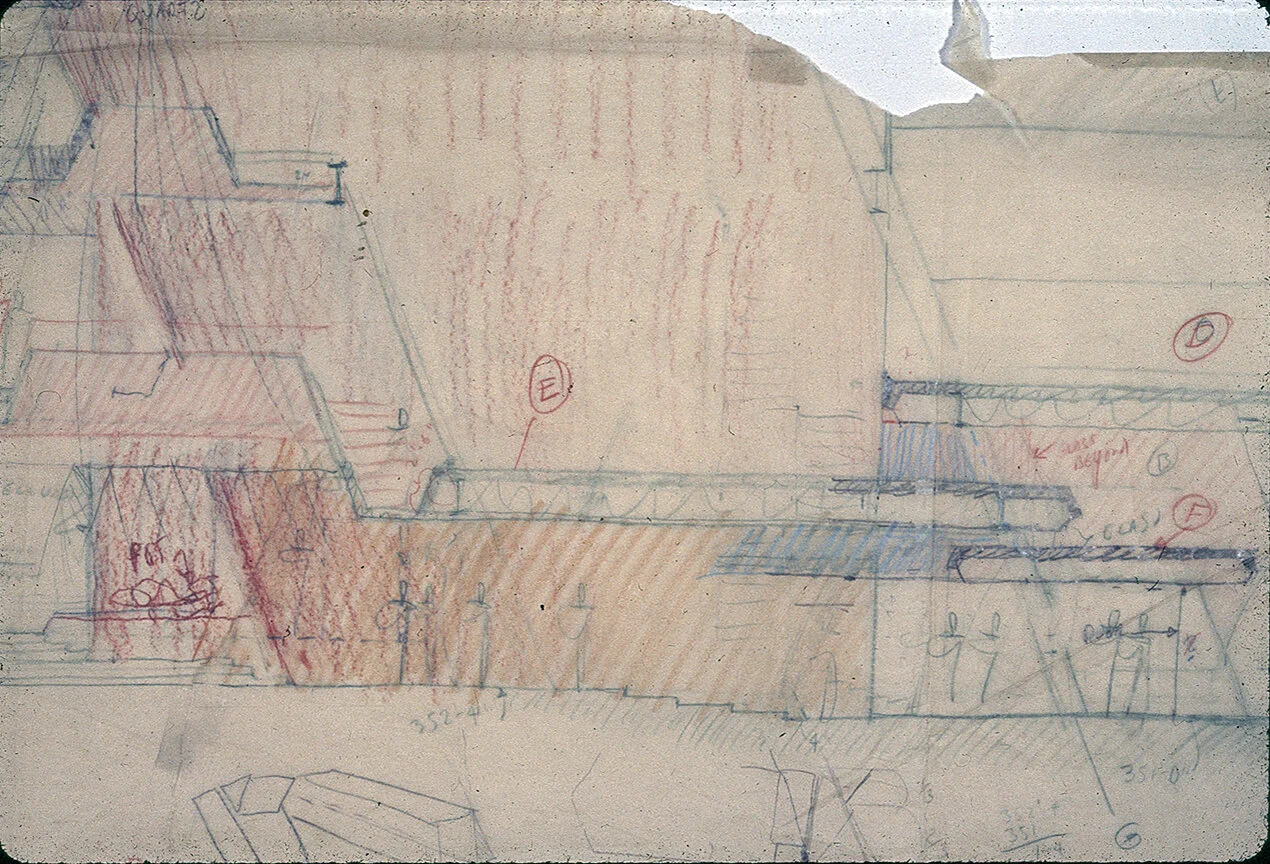

DRAWINGS - Design Drawings / Renderings

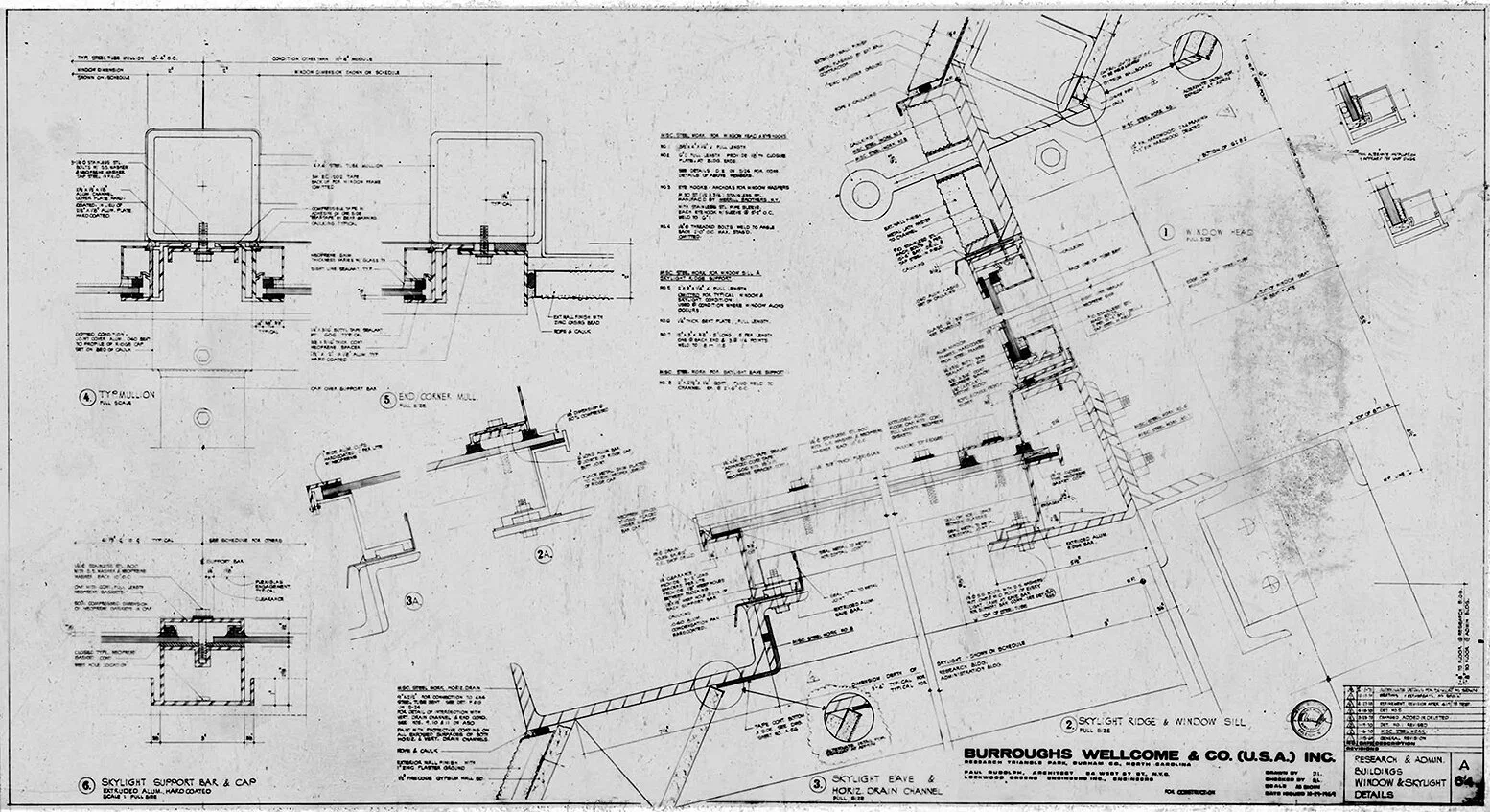

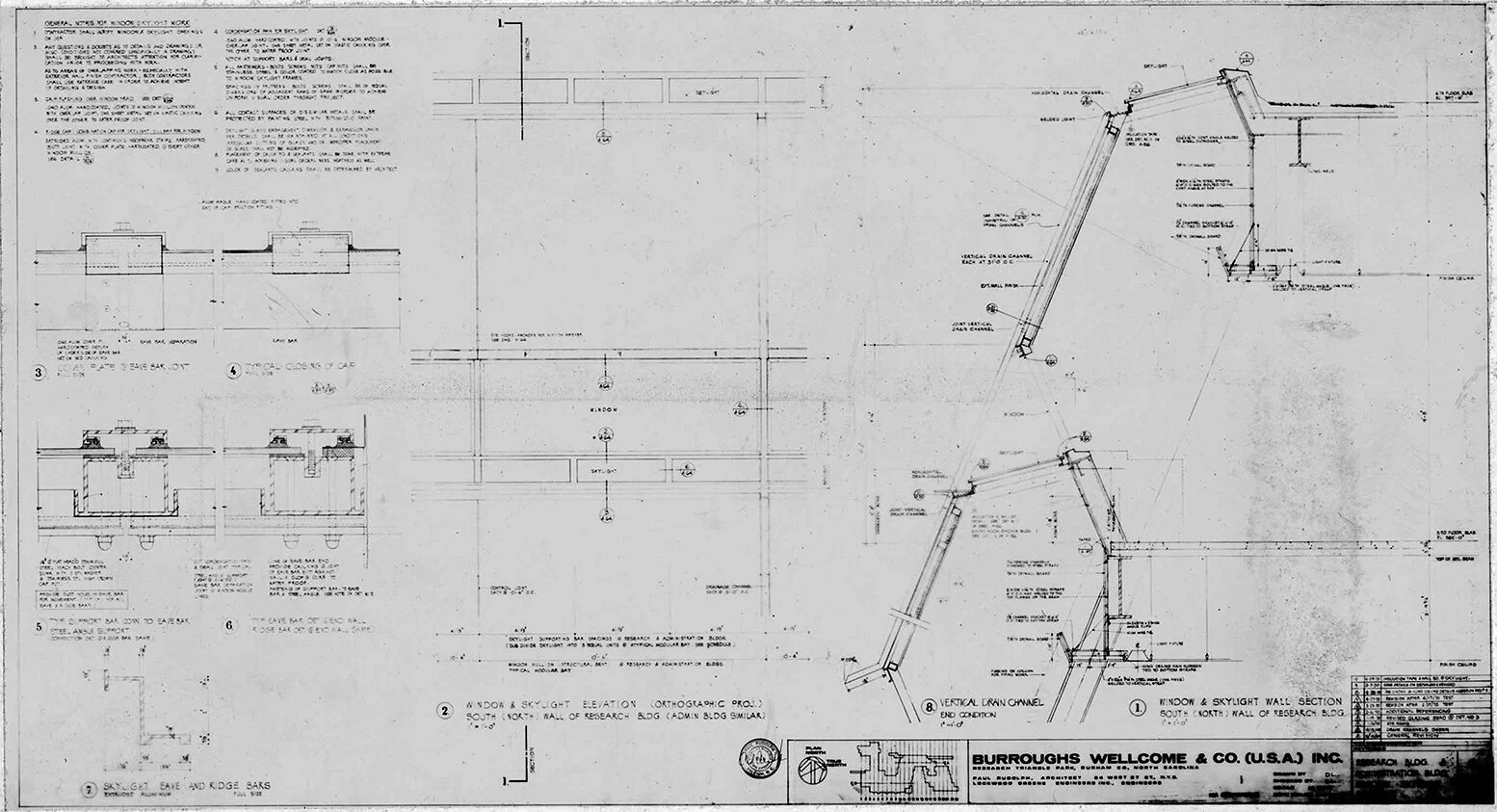

DRAWINGS - Construction Drawings

DRAWINGS - Shop Drawings

PHOTOS - Project Model

PHOTOS - During Construction

PHOTOS - Completed Project

PHOTOS - Current Conditions

LINKS FOR MORE INFORMATION

Petition to Save the Building from Demolition

Elion-Hitchings Building on Emporis website

Burroughs-Wellcome Building on the DocomomoUS website

Video of the 2012 public tour by qbismCom - October 20, 2012

Animated photo of Burroughs Wellcome Company Lobby by Grit Velvet - January 10, 2017

Video of the building’s interior ‘Diagonal Movement’ by Aidan Wells & Griffin Kaiser - August 08, 2017

Video of the current building exterior by Mauricio Castro - November 9, 2018

RELATED DOWNLOADS

Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) report No. NC-418 prepared by the Heritage Documentation Programs division of the National Park Service

PROJECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

“A New Environment for Research.” Terre Haute Saturday Spectator, May 20, 1972. p. 54

Alexandra Lange. “How to Save a House.” Town & Country, Apr. 2021, pp. 74–77.

Alfred M. Kemper. Drawings by American Architects. Wiley, 1973.

Amanda Hoyle. “UT deepens stake here with RTP Purchase” Triangle Business Journal, June 29, 2012.

Barclay F. Gordon. Interior Spaces Designed by Architects. McGraw-Hill, 1974.

“Burroughs Wellcome & Co. Building.” Architecture and Urbanism, no. 80, July 1977.

“Burroughs Wellcome & Co. Building.” Architecture and Urbanism, no. 80, July 1977, pp. 196–201.

“Burroughs Wellcome Co. Building.” Architecture and Urbanism, no. 3, Apr. 1973, pp. 23–30.

“Chronological List of Works by Paul Rudolph, 1946-1974.” Architecture and Urbanism, no. 49, Jan. 1975.

“Drawings and Sketches of Paul Rudolph.” Architecture and Urbanism, no. 49, Jan. 1975.

G. E. Kidder Smith. A Pictorial History of Architecture in America. American Heritage, 1976.

“Here Are the Controversies That Drew Ire in 2021.” The Architect’s Newspaper, 28 Dec. 2021.

Jeanne M. Davern. Architecture 1970-1980: A Decade of Change. McGraw-Hill, 1980.

Joseph W. Molitor. Architectural Photography. Wiley, 1976.

Laura Oleniacz. “‘Iconic’ GSK building up for sale” The Herald Sun, 2011.

Mildred F. Schmertz. Office Building Design. 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill, 1975.

---. “Paul Rudolph: Work in Progress.” Architectural Record, no. 148, Nov. 1970.

Nicholas Som. “Lost: Burroughs Wellcome Headquarters.” Preservation, vol. 73, no. 2, Apr. 2021, p. 7.

Paul Goldberger. “Architecture: Show of Rudolph’s Work.” The New York Times, 5 July 1979.

Paul Rudolph. Paul Rudolph: Dessins D’Architecture. Office du Livre, 1974.

Paul Rudolph and Sybil Moholy-Nagy. The Architecture of Paul Rudolph. Praeger, 1970.

“Public Library for the City of Niagara Falls.” Architectural Record, no. 157, June 1975, pp. 96–100.

Roberto De Alba. Paul Rudolph: The Late Work. Princeton Architectural Press, 2003.

“Sculptural Forms for Pharmaceutical Research.” Architectural Record, no. 151, June 1972, pp. 95–100.

Tony Monk. The Art and Architecture of Paul Rudolph. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 1999.

“Ventidue Gradi A Mezzo.” Architettura, no. 18, Dec. 1972.

Victoria Ballard Bell. Triangle Modern Architecture. ORO Editions, 2020.