Welcome to the Archives of The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture. The purpose of this online collection is to function as a tool for scholars, students, architects, preservationists, journalists and other interested parties. The archive consists of photographs, slides, articles and publications from Rudolph’s lifetime; physical drawings and models; personal photos and memorabilia; and contemporary photographs and articles.

Some of the materials are in the public domain, some are offered under Creative Commons, and some are owned by others, including the Paul Rudolph Estate. Please speak with a representative of The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture before using any drawings or photos in the Archives. In all cases, the researcher shall determine how to appropriately publish or otherwise distribute the materials found in this collection, while maintaining appropriate protection of the applicable intellectual property rights.

In his will, Paul Rudolph gave his Architectural Archives (including drawings, plans, renderings, blueprints, models and other materials prepared in connection with his professional practice of architecture) to the Library of Congress Trust Fund following his death in 1997. A Stipulation of Settlement, signed on June 6, 2001 between the Paul Rudolph Estate and the Library of Congress Trust Fund, resulted in the transfer of those items to the Library of Congress among the Architectural Archives, that the Library of Congress determined suitable for its collections. The intellectual property rights of items transferred to the Library of Congress are in the public domain. The usage of the Paul M. Rudolph Archive at the Library of Congress and any intellectual property rights are governed by the Library of Congress Rights and Permissions.

However, the Library of Congress has not received the entirety of the Paul Rudolph architectural works, and therefore ownership and intellectual property rights of any materials that were not selected by the Library of Congress may not be in the public domain and may belong to the Paul Rudolph Estate.

LOCATION

Address: 106 Central Street

City: Wellesley

State: Massachusetts

Zip Code: 02481

Nation: United States

STATUS

Type: Academic

Status: Built

TECHNICAL DATA

Date(s): 1955-1958

Site Area:

Floor Area:

Height:

Floors (Above Ground):

Building Cost:

PROFESSIONAL TEAM

Client: Wellesley College

Architect: Paul Rudolph (1918-1997)

Associate Architect: Anderson, Beckwith & Haible

Landscape:

Structural: Goldberg, Le Messurier & Associates

MEP: Stressenger, Adams Maguire & Reidy

QS/PM:

Acoustical: Bolt, Beranek & Newman

SUPPLIERS

Contractor: George A. Fuller Co.

Subcontractor(s):

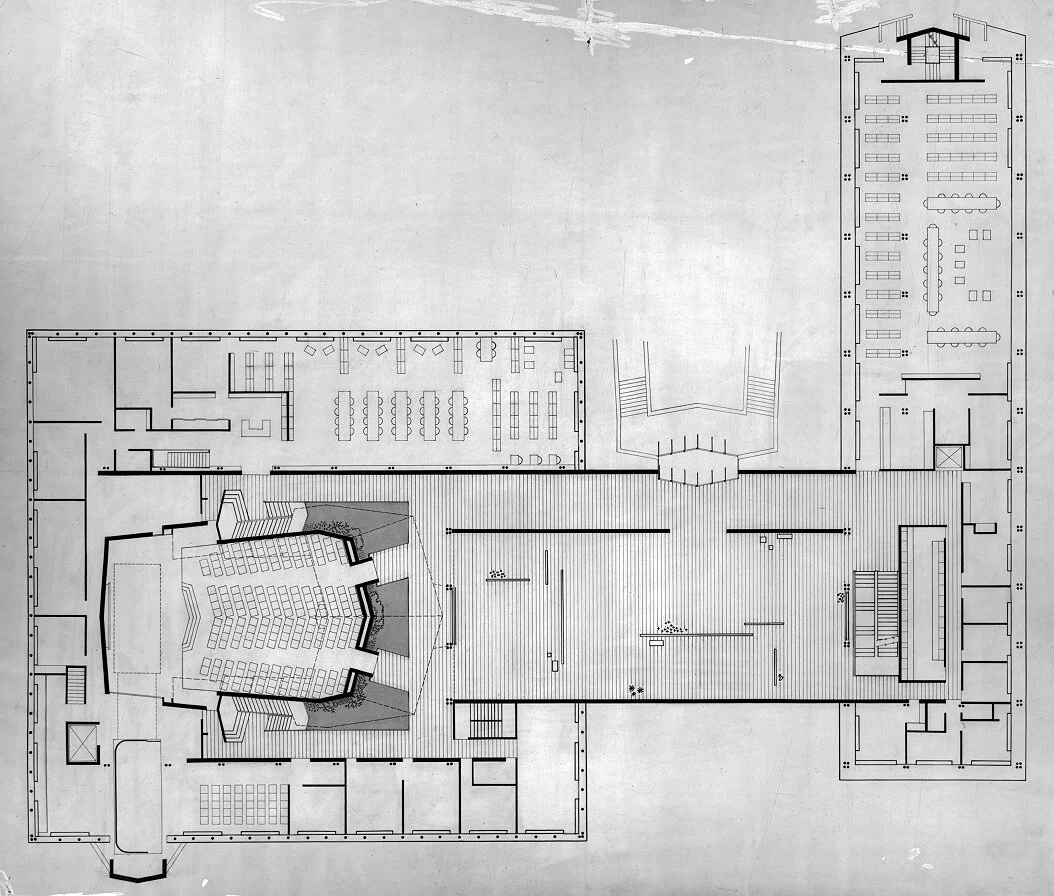

Mary Cooper Jewett Arts Center for Wellesley College

The building is a gift of the George Frederick Jewett family.

In 1993 the Davis Museum and Cultural Center, the $11.7 million USD building the first in North America designed by Pritzker Prize-winning architect Rafael Moneo, opens to the public. It is connected by an enclosed bridge to the Jewett Arts Center.

In 2015 the Getty Foundation issues a $120,000 USD grant as part of its Keeping It Modern grant initiative focused on supporting model projects for the conservation of modern architecture. The grant supports a conservation management plan that prioritizes the retention of the building’s historic fabric in future planning, makes better use of existing spaces, and develops a treatment protocol for significant building components.

“The next example is designed and controlled and calculated to the inch. It is in fact one single building, Paul Rudolph’s Fine Art Center at Wellesley College; the sequence is the flight of steps that leads up under it to come out in the quad facing the Neo-Gothic buildings of a generation ago. That is, exactly, a microcosm of of the problems that face - or ought to face - a town planner or a town maker joining old to new, making the town a space for living in. The judgement and artistry and control shown by Rudolph here - for the spatial sequence is one of the great things in American architecture, New England’s own Spanish Steps - are basically the qualities required by any city engineer who plans a new system of sidewalks.

... The sequence starts by being what seems to be simply a deeply inset entrance to the building. That it is not, that there is something else beyond, is one of the fundamental tricks of this trade, a trade which in many ways is like the art of the striptease. Striptease is a matter of alternate tease and strip, tension between yes and no. After a qualified no of the first view comes a tantalizing yes as soon as you are on the axis, when the entrance is seen to be steps, with, at the end, an entirely unexpected glimpse of the sunlit quad and other buildings beyond. Clearly this is going somewhere.

... Up the few steps and the stairs have got us. Not the steps straight ahead, but the pair of staircases which seems to be descending about out ears. These stairs are the visual equivalent of musical counterpoint, or an abrupt change of direction on a roller coaster. They cut into the whole forward pattern of motion - especially and cruelly in the exposed undersides of the treads, like seeing your own skeleton walking beside you. They are beautifully controlled- they only cut into the motion, hence enrich it, they do not stop it. Along the level a little further, up three more steps, along again (not quite so far, four paces instead of six; the pace is quickening, and although both get tto the same place with the same number of units), up three more steps, with the buildings at the end visibly Neo-Gothic now (i.e., different from what we are in: “There” instead of “Here”) and are just begining to wind up and give the stairways impetus, when - Bang! - a who new dimension has exploded into view...

... It is like an electric shock, or drinking a glass of neat bourbon when you expected lemonade. And to let it sink in, there is a long caesura, a halt in the steps.

... Wellesley has been described in such detail because it is the perfect example of the kind of tools a townscaper needs.”

“The problem was to add to a pseudo-gothic campus in such a way as to enhance the existing campus and still make a valid twentieth century building. The siting manipulation of scale, use of materials, and silhouette helped to extend the environment. The sequence of spaces leading under the connecting bridge up to the raised courtyard and the tower beyond works, but the interior spatial sequence is unclear, overly detailed and in many cases badly proportioned.”

“... the Jewett is a snapshot of a marvelous time, a brief moment when Mr. Rudolph’s brilliant compositional sense was married to the lightness of his earlier work.”

DRAWINGS - Design Drawings / Renderings

DRAWINGS - Construction Drawings

DRAWINGS - Shop Drawings

PHOTOS - Project Model

PHOTOS - During Construction

PHOTOS - Completed Project

PHOTOS - Current Conditions

LINKS FOR MORE INFORMATION

The Jewett Arts Center: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow website hosted by Wellesley College

The Keeping It Modern list of 2015 grants issued by the Getty Foundation

RELATED DOWNLOADS

PROJECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arthur Drexler. Transformations In Modern Architecture. Museum of Modern Art, 1979.

“Bright New Arrival.” Time, no. 75, 1 Feb. 1960.

“Chronological List of Works by Paul Rudolph, 1946-1974.” Architecture and Urbanism, no. 49, Jan. 1975.

Corrado Gavinelli. Architettura Contemporanea: Dal 1943 Agli Anni ’90. Jaca Book, 1995.

Cranston Jones. Architecture Today and Tomorrow. McGraw-Hill, 1961.

Ernst Danz. Sun Protection. Verlag Gerd Hatje, 1967.

“Fitting the Future Into the Past; Mary Cooper Jewett Arts Center, Wellesley College.” Architectural Forum, no. 105, Dec. 1956, pp. 100–06.

Fumihiko Maki. Contemporary Architecture of the World, 1961. Shokokusha, 1961.

“Genetrix: Personal Contributions to American Architecture.” Architectural Review, no. 121, 121, May 1957.

Henry A. Millon. “Rudolph at the Crossroads.” Architectural Design, no. 30, Dec. 1960, pp. 497–99.

Ian McCallum. Architecture USA. Reinhold, 1959.

Ian Nairn. The American Landscape: A Critical View. Random House, 1965.

James P. Warfield. Paul Rudolph: 1983-1984 Receipient of the Plym Distinguished Professorship. School of Architecture, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1983.

“Jewett Arts Center.” Architecture and Urbanism, no. 80, July 1977, pp. 220–23.

Joan E. Goody. New Architecture in Boston. MIT Press, 1965.

John Cook and Heinrich Klotz. Conversations With Architects. Praeger, 1973.

John Jacobus. Twentieth Century Architecture: The Middle Years 1940-1965. Praeger, 1966.

John Peter. Design With Glass. Reinhold, 1964.

“Kunstsentrum Der Universitat Wellesley, Mass. / USA.” Deutsche Bauzeitung, no. 66, Dec. 1961, pp. 936–39.

Mardges Bacon. John McAndrew’s Modernist Vision. Princeton Architectural Press, 2018.

Mark Gunderson. “Rudolph and Texas.” Texas Architect Magazine, June 1998.

“Marriage of Heaven and Hell: Art, Music, and Drama Center at Wellesley.” Interiors, no. 121, Feb. 1962.

“Mary Cooper Jewett Arts Center at Wellesley.” Architectural Record, no. 121, Feb. 1957, pp. 166–69.

“New Architecture in an Old Setting.” Architectural Record, no. 126, July 1959, pp. 175–86.

“Not Neo-Tiffany: Jewett Arts Center.” Architectural Review, no. 127, Feb. 1960, p. 78.

Paul Goldberger. “Sensuous Spaces Armored in Brick.” The New York Times, 31 July 1994.

“Paul Rudolph.” Architecture D’Aujourd’hui, no. 28, 28, Sept. 1957.

---. Paul Rudolph: Dessins D’Architecture. Office du Livre, 1974.

Paul Rudolph and Sybil Moholy-Nagy. The Architecture of Paul Rudolph. Praeger, 1970.

Peter Collins. “Whither Paul Rudolph?” Progressive Architecture, no. 42, Aug. 1961.

Peter Fergusson, et al. The Landscape & Architecture of Wellesley College. Wellesley College, 2000.

Philip Johnson. “Three Architects.” Art In America, no. 48, Spring 1960, pp. 70–73.

Ralph Warner Hammett. Architecture in the United States: A Survey of Architectural Styles Since 1776. Wiley, 1966.

Robert A. M. Stern. New Directions in American Architecture. Braziller, 1969.

---. New Directions In American Architecture. Braziller, 1977.

Roberto De Alba. Paul Rudolph: The Late Work. Princeton Architectural Press, 2003.

“Rudolph Buildings at Yale and Wellesley Open.” Progressive Architecture, no. 40, July 1959, p. 87.

Rupert Spade. Paul Rudolph. Simon and Schuster, 1971.

“Scuola D’arte a Wellesley.” Edilizia Moderna, no. 68, Dec. 1959.

“Scuola D’Arte Mary Cooper Jewett al Wellesley College, Wellesley, 1959.” Casabella, no. 234, Dec. 1959, pp. 18–25.

“Selearchitettura: Il Futuro Nel Passato.” Architettura, no. 2, Apr. 1957, pp. 880–81.

Tony Monk. The Art and Architecture of Paul Rudolph. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 1999.

“Travaux Recents De Trios Agences Americaines.” Architecture D’Aujourd’hui, no. 30, Sept. 1959, pp. 33–40.

“Wellesley’s Alternative to Collegiate Gothic.” Architectural Forum, no. 111, July 1959, pp. 88–95.

William Menking. “Manhattan Masterpiece.” The Architects’ Journal, 28 Oct. 2004.

“30 Works To Be Exhibited At Pre-Ball Arts Show.” Cedar Rapids Gazette, January 24, 1965. p. 73

Jarman, E. C. (1959, November 15). Forum Features Rudolph Job. Sarasota News, p. 15

“Rudolph Cited By Magazines.” Sarasota News, December 23, 1956. p. 30