Rudolph in a happy mood, at the street level of one of his most compelling buildings: his about-to-be-completed Temple Street Garage in New Haven.

It’s October 23—and we celebrate Paul Rudolph’s Birth 101 years ago today (and invite you to do so too!)

This past year—Rudolph’s centenary—has been a year of “Rudolph-ian” accomplishment: in preservation, research, education, scholarship, and—perhaps most important—in creating a growing awareness and appreciation of the legacy of this great architect. But—

But rather than review the achievements of the last year (you can read of many examples in past articles on this blog) we thought it would be nice to just share some images of him—and different ones than you normally see.

Portraits of architects usually show them in a serious mode, with solemn expressions suitable for a person embarking on a great artistic or constructional task. Paul Rudolph was no exception: most pictures of him show a deeply thoughtful figure, or one engaged in disciplined, critical work.

But today we offer a couple of pictures of another, sunnier side of Rudolph—ones where the architect was clearly in a smiling, happy state.

Paul Rudolph in formal attire—with more than a hint of a smile. By-the-way: that’s not smoke in the background (as we had first thought—but Rudolph was never a smoker.) What’s [visually] suggesting smoke is light catching the curving edges of a topographic model., shown here tipped vertically to hang on a wall. Such models are part of the architectural design and presentation process—and this one might have been made, in Rudolph’s office, for one of his projects.

![Paul Rudolph in formal attire—with more than a hint of a smile. By-the-way: that’s not smoke in the background (as we had first thought—but Rudolph was never a smoker.) What’s [visually] suggesting smoke is light catching the curving edges of a topo…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1571777213382-QGDGH7LPXF8Z7BKOURQM/Rudolph+in+tux.jpg)

![Two approaches to drawing a rectilinear volume (which could be a brick, a building, a part of a building, or a room…):The isometric Drawing, at the far-Left, distorts the top and bottom [plan] surface, and all the other planes too—making them into d…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1569611468636-M4EYPT5S2Q16MOXPGFUD/axonomtric%2Bdiagram-two%2Bangles.jpg)

![Three key players: [left-to-right] Cheng Yang “Bryan” Lee, the museum’s curator; Liz Waytkus, Executive Director of DOCOMOMO US, and Barbara Campagna, leading preservationist—and co-curator of the exhibit. Photo by Joanne Campagna. [Photo by Barbara…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1570474994444-UNRO3XH2XWAF4K5F6HGB/71722422_10220079287277662_7020131205022482432_n.jpg)

![William Vogel, El Museo’s executive director, works on the exhibit’s signage. [Photo by Barbara Campagna]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1570476091596-HAXYDAI4D5EQ77Q6MW77/71521918_10220079310598245_6736057541169512448_n.jpg)

![The venue for the exhibit: El Museo in Buffalo—and the public is welcome! [Photo by Barbara Campagna]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1570476537444-GIA136EV1H7MH9D2CGBW/71769817_10220079871532268_7274995981706330112_n%2B%25281%2529.jpg)

![A view from the back of the exhibit space, looking towards the entrance—with attendees carefully studying the displayed materials. [Photo by Barbara Campagna.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1570475078742-7M7V7Q5MNL04MUKB90ST/71372038_10220079296277887_1751663417665519616_n.jpg)

![Barbara Campagna reported that it was a “Jam packed museum exhibit opening…”—and the photos testify the same. [Photo by Barbara Campagna]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1570475212368-SHX1I8RXVZDGU4X2M1H2/72435449_10220079872052281_18601048092442624_n.jpg)

![More of Paul Rudolph’s drawings, as displayed on the exhibit’s walls—and in the foreground is one of Kurt Treeby’s architecturally-focused artworks. [Photo by Barbara Campagna]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1570475874812-WJLI7VOLMV3YF9G7OKPL/72111388_10220079289357714_2001563671716691968_n.jpg)

![Bryan Lee, the exhibit’s co-curator (far left), gives an overview of the Shorline project and exhibit. [Photo by Barbara Campagna]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1570471230922-2B99XX9S6JH9UCBJLSJ7/71839761_10220079293117808_6423355364783161344_n.jpg)

![In addition to drawings and artworks, photos of were included—including of its littlest residents, as well as interiors—and this gave a sense of life in Shoreline. [Photo by Barbara Campagna]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1570476200652-HPPE35B2LI63IEXUS8QB/71806244_10220079301118008_4407627569529094144_n.jpg)

![Kurt Treeby—the artist with one of his works. [Photo by Barbara Campagna]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1570475336662-FLBGEHWZV8MK7IMYFSGF/72380245_10220079299677972_3125936434217746432_n.jpg)

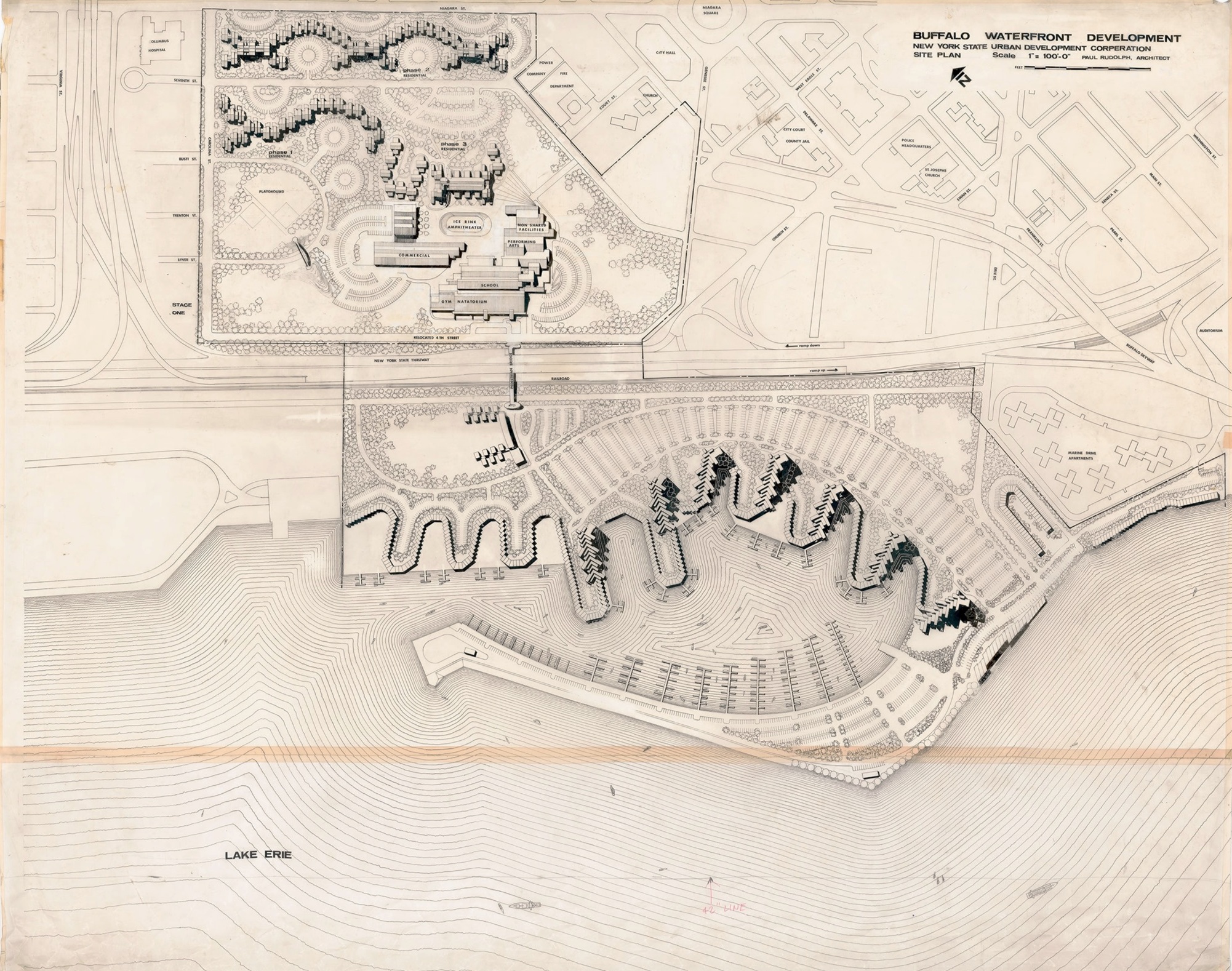

![A artifact of Buffalo’s history—and of the aspiration to use architecture to make better lives. [Photo from a post by Barbara Campagna]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1570470560363-GJ7V050VQ2QRJ09QK8DN/72703588_10220071593845331_4016297117617225728_n.jpg)

![An exterior side elevation of the terminal building. The capsule-like control tower [another saucer?—perhaps Rudolph saw Wright’s renderings?] is in the background at the right. The building’s columns appear to flare outward at their tops: a form re…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1563827539259-S0MVUHOMK3FBK8X4W0EP/Airport+side+elevation.jpg)