A FASCINATING HOUSE

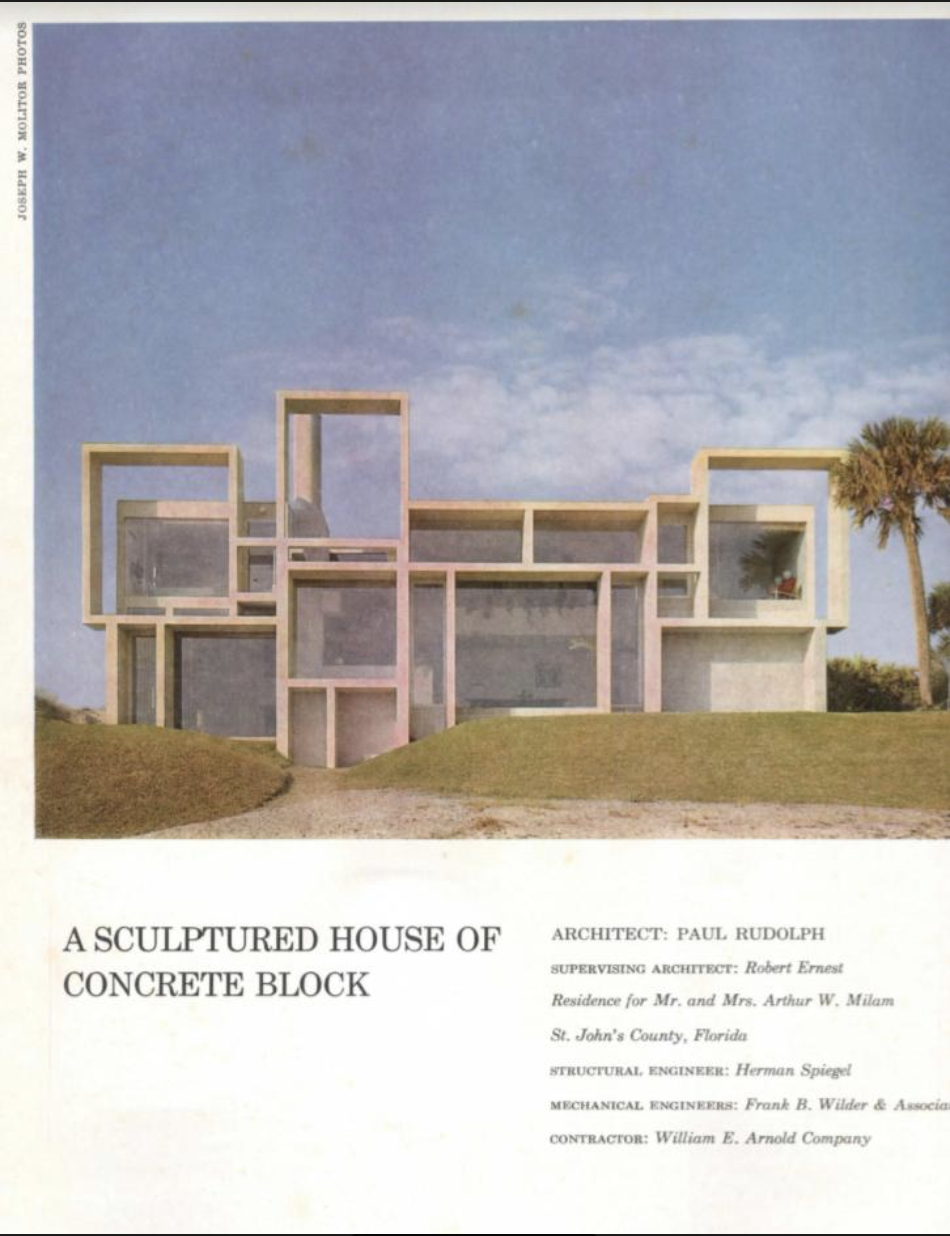

Our recent article about the Milam Residence went viral—and so we thought it would be good to share some more information about this landmark of 20th century design. Here, we’ll cover two other interesting aspects of the building: the story of its construction, and how the design was received by the architectural and lifestyle press.

BUILDING AN ICON

We asked the Robert C. Champion, the son of the original owner, to tell us about the origin of the project, including the Milam’s relationship with Rudolph. He answered several of our questions:

Q: Do you know anything about the relationship between your parents and Rudolph, and how they found-out about him?

A: My stepfather, Arthur Milam, knew of Rudolph’s work in Sarasota. My stepfather was a graduate of Yale Class 1950. Rudolph became Chair of Yale Architecture in 1958, so they had a common bond. Also my stepfather was a big collector of modern art, so he was interested in an architect and specialized in modern art.

Q: Do you know what “program” they presented to Rudolph (what set of requirements he was asked to fulfill?)

A: My stepfather gave Rudolph free rein to design the house. He did tell him how much square footage and how many bedrooms, but other than that he left the whole creation to Rudolph.

Q: Do you know how the architect-client relationship went with them all? [We’re guessing they got along pretty well, as Rudolph was invited back to do the additions/alterations.]

A: They got along very well as far as I know. My stepfather left the creating to Rudolph.

Q: Did you hear anything about the construction period—for example: stories about things that needed adjusting because of site conditions?

A: Rudolph wanted to build the house in poured concrete and rebar. When they calculated the cost it was very cost prohibitive so they changed it to concrete block with rebar and all concrete poured cells.

Q: Was this a year-round residence—or—primarily a vacation home?

A: It was a year-round residence.

Q: Any reflections of your own, about growing-up in it?

A: It was by far the largest home in north Florida when it was built. Most of the homes on the ocean were second homes and were cottages made out of cedar. So this house really stood out. It was known as the crazy house of rectangles and was labeled so on the fisherman’s map. We had very few neighbors back then. We had one neighbor a half mile to the north and another a half mile to the south.

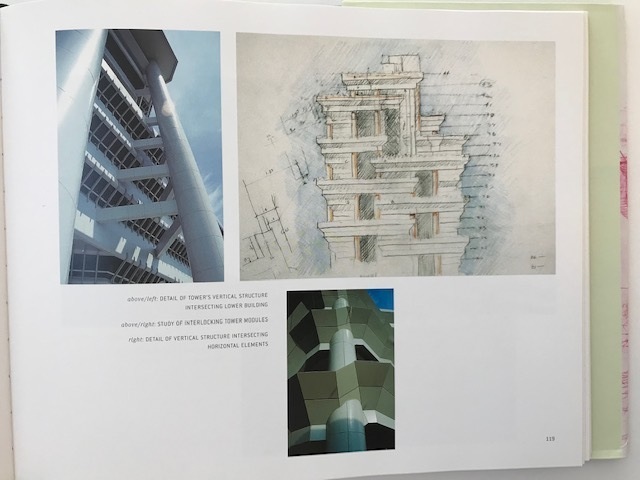

Mr. Champion’s notes about the Milam’s initial knowledge of Rudolph meshes well with the information in a fascinating document: the National Register of Historic Places’ Registration Form for this building—which is also linked-to on the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s Project Page for this house. The National Register’s document gives a complete history of the site and context---both physical, historical, and cultural—and a detailed description of the building, inside-and-out. It also includes an evaluation of the building’s significance and how it fits into Rudolph’s overall oeuvre, as well as drawings, maps, and photographs.

The building went through several phases:

Original state: As designed by Paul Rudolph, for Arthur and Teresa Milam—with the house being occupied at the beginning of the 1960’s.

Alterations by Rudolph: Rudolph was brought back more-than-once, by the Milams, to make alterations and/or additions. Their extent is well described in the National Register’s report:

“After the house was complete, the Milams contacted Paul Rudolph for his design services once again. In the early 1970s, Milam had Rudolph add two ancillary structures on either side of the main house—one for a three car garage and one for a guest house/studio. Rudolph used the same materials and design vocabulary for the new wings. The two original garages, which flanked the house to the north and to the south, have been converted into a dining room (on the north side), and an office (on the south side). The addition, which runs perpendicular to the house on the south side is a guest house/office. The pool is on the west side of a courtyard, with the house on the east facing the ocean. So it fits together around the center courtyard. In 1973, Paul Rudolph designed a smaller addition southwest of the main house that serves as another family room with a downstairs bath and upstairs sleeping loft. A breezeway connects it to the main house. The original south garage was converted into an office, with a folding partition that hides away storage. This alteration connects to the breezeway and does not significantly alter the building’s facade. This alteration is complementary to Rudolph’s design and to his 1973 addition. During the Rudolph addition, phase, Teresa Milam redesigned the original kitchen. These additions and alterations are sympathetic to the overall vision of Paul Rudolph, and are considered to be contributing elements.”

Post-Rudolph: After Rudolph’s passing, KBJ Architects (a prominent Florida architectural firm, based in Jacksonville) was asked to add a weight room and an additional garage.

AN INFLUENTIAL DESIGN

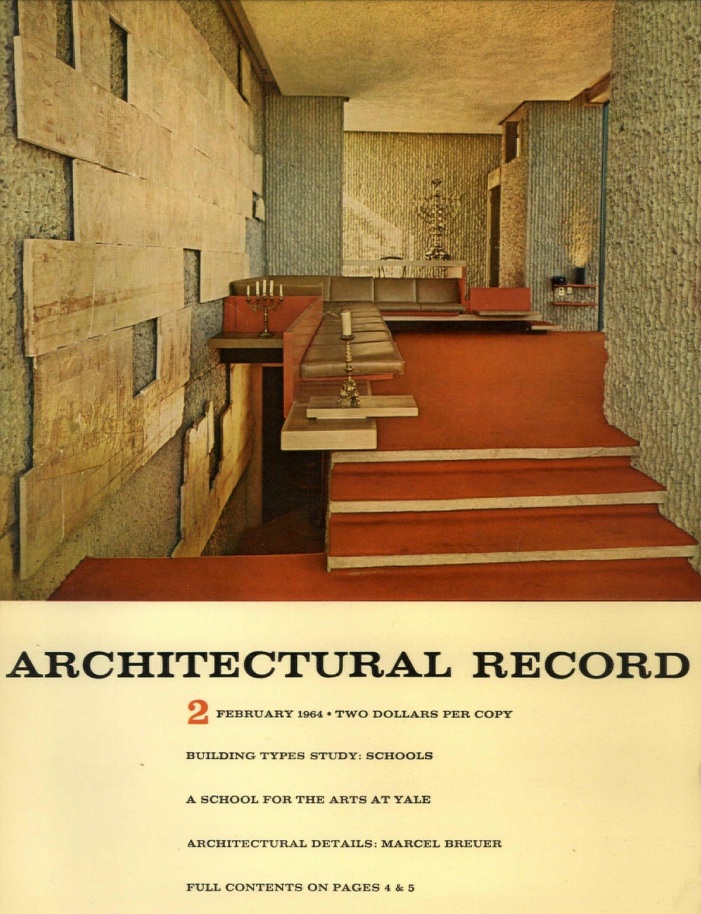

Robert Adams Ivy, Jr., the editor of Architectural Record, told Ernst Wagner (founder of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation) that when the Milam Residence was published, it was a powerful and compelling design—and that it influenced a whole generation of architects.

The evidence is strong that this was a remarkable design for it’s time—in that it was widely noted and remarked upon by the editors and writers of architectural and lifestyle publications. Both American and international magazines covered the Milam Residence, either focusing on it individually, or including it as an indicator of larger trends in contemporary architectural design.

Prominent among the magazines which published the house (near the time of its completion) were:

Architectural Record (three times)

House and Garden

Vogue

Architectural Design (UK)

House and Home

Architecture D’aujourd’hui (France)

Architettura (Italy)

Zodiac (Italy)

The coverage seems to have, near-universally, given praise: either about the house itself, or about it as a representative of positive trends in residential design, or about its architect. Here are some examples:

HOUSE AND HOME:

Their April 1964 issue had an article about Modern trends in home design, “Three Houses WIth Daring New Shapes,” and illustrated it with designs by Eric Defty, John Rex, and Paul Rudolph. The introduction explained their viewpoint—and mentions Rudolph’s house with praise:

“Architecture worthy of the name never leaves the viewer bored. It is dynamic, exciting and often daring because the juxtaposition of shapes and volumes sets up a flow of space related to the textures, patterns and colors in the house. Often, it artfully contrasts a sense of openness with the security feeling of shelter. Too many of today’s houses are familiar, static and so impersonal they hardly qualify as architecture. Not so the houses shown at the right and on the following pages. Architect Paul Rudolph’s beach house in Jacksonville, Fla. has a three dimensional facade of concrete block that spells out the interior arrangement of rooms and floor levels. The working facade—some architectural critics believe it has started a whole new trend in design—is a series of deep squares and rectangles that look out on the sea and shade the interior. Inside the house, seven floor levels follow the pattern of the facade and help define the flow of space.”

The article’s extended captions pointed-out various features of the house’s design:

“Changing levels and varied ceiling heights emphasize the different uses of space in Architect Paul Rudolph’s concrete-block beach house. For example: the floor plane drops to form a big conversation pit in the high-ceilinged living room, then rises two steps in the rear to the open dining room and rises another three steps to an intimate, low-ceilinged inglenook. Space flows smoothly from one area to another.

Plan orients the active living areas and master bedroom to the sea. The basic planning module is the length of a concrete block. View of ocean, seen here from the dining room is framed by deep sun-breaks. The conversation pit is in foreground, the inglenook at right. View of living and dining areas from the inglenook in the foreground shows variety of floor levels and ceiling heights. Moors arc terrazzo. Facade on the sea is a geometric arrangement o f sun-breaks , or brise-soleils , that hint at the interior arrangement of space. Sand-colored concrete-block rectangles are deep enough to shade the interior and help keep the house cool without drapes which would block the magnificent ocean view. The lowest sun- break, at lower left, frames a utility room; the highest make a rooftop lookout — a widow’s walk in a modern idiom.”