A personal note from Rudolph may hint at his questioning—even late in his career.

Kickstarter Campaign Launched to Render Rudolph Project

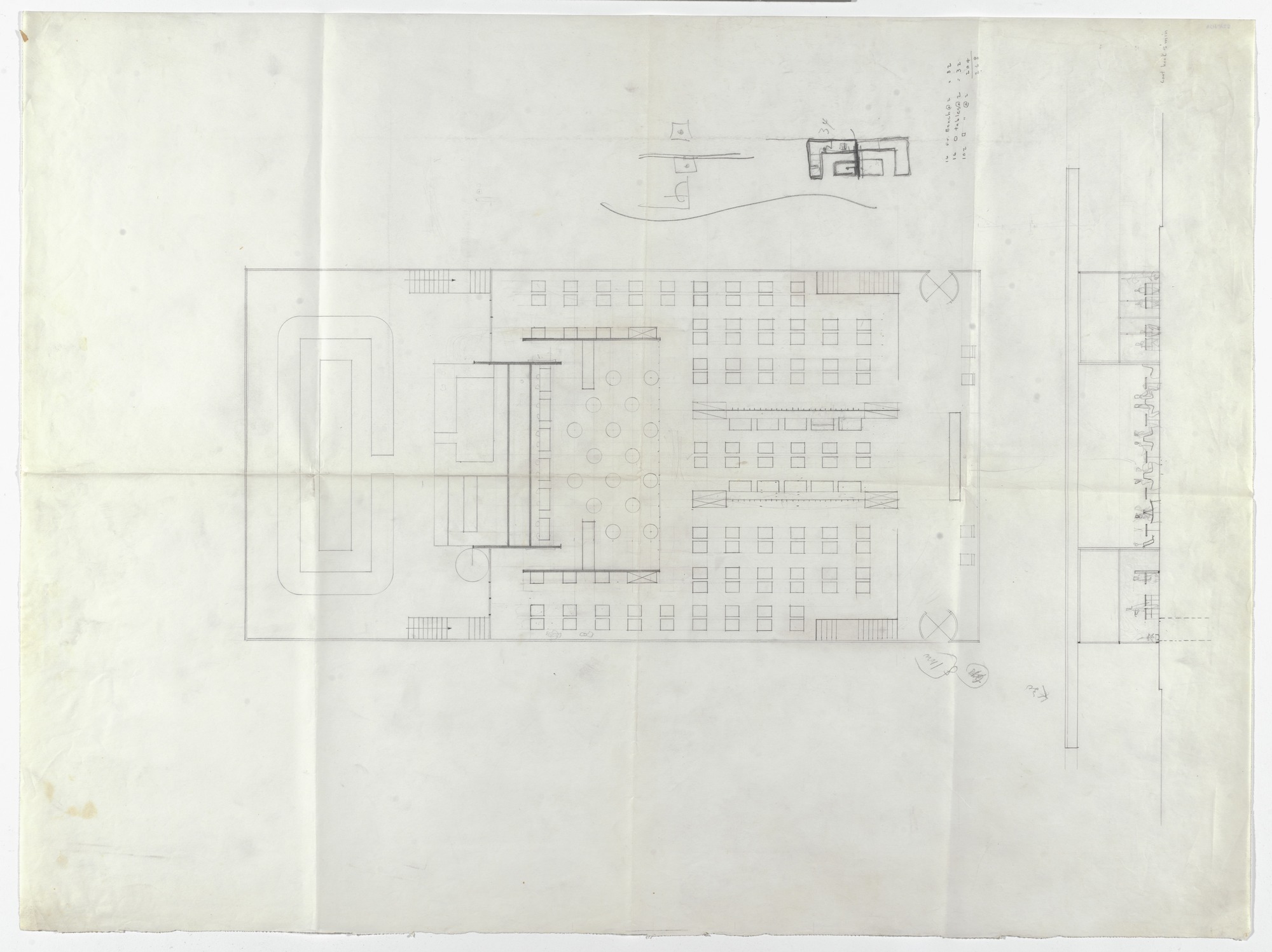

Rudolph’s Perspective Rendering of the unbuilt Gatot Subroto project for Jakarta, Indonesia. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

A Kickstarter campaign has been launched by researcher and author Eric Wolff to professionally render one of Paul Rudolph’s little-known late works, the unbuilt Gatot Subroto project in Jakarta, Indonesia.

From the kickstarter site:

Some refer to his late works in Asia as ”seven buildings including a couple of villas” and describe Rudolph’s late career as a kind of afterthought to a, at times controversial but, prolific career. My research into Rudolph’s archives, interviews with his office personnel and visits to his buildings in Asia, reveal that Rudolph‘s late career period was not only bountiful, but reflects a period where Rudolph was performing at the peak of his capabilities and sensibilities producing some of his finest works ever. In his late career (1978 - 1997), Rudolph participated in about 50 projects and completed upwards of 20 buildings in Asia, cementing his place alongside, and sometimes in direct competition with, architectural titans like Richard Meier, I.M. Pei, Kenzo Tange and John Portman. Rudolph’s late works are not well known and have not been fully evaluated, in this project I am recreating select Paul Rudolph buildings digitally from his archived drawings/material and rendering them into illustration.

Importantly, many of the ”undiscovered” Asian works exemplify Rudolph‘s specific contributions to Modernist Architecture. You do not have to love Rudolph's buildings to appreciate that he pushed the envelope in terms of sculptural design; but he also innovated in areas of sustainability and structure. In this project I will illustrate the ambitious Gatot Subroto (unbuilt), that was designed for Jakarta, Indonesia as an ”office village” with 875,000 square feet of office space, and 450,000 square feet of parking. The outcome will be a full color poster sized realistic rendering of the Gatot Subroto at dusk, as well if budget allows several close up realistic renderings of the buildings interior and roof garden spaces.

The late works in Asia demonstrate how the Modernist principles base of Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright were combined and evolved by Paul Rudolph to create a unique new vocabulary that would inspire today’s contemporary architects.

The Gatot Subroto (Jakarta, Indonesia 1990) is an example of Rudolph’s unique point of view. The client requested eight towers to be developed on an existing property as an office condominium complex in which the Dharmala group would occupy part of the space. Rudolph’s initial designs reflected the request of eight towers, joined by floors spanning the complex reading as a ”perforated wall”. The client wanted a more cohesive look from the busy street and in order to attract top clients, did not want their own anchor space to dominate the design. Rudolph, heeding the client feedback, in his final design created a masterpiece!

The Gatot Subroto represents one of the earliest examples of sustainability in architecture. its windows are slanted and shaded to deflect the mid-day Indonesian sun. Between the cantilevered three floor blocks are void-decks capped with roof garden terraces, increasing the green factor higher than the buildings footprint. A testament to sustainability before it was even in fashion.

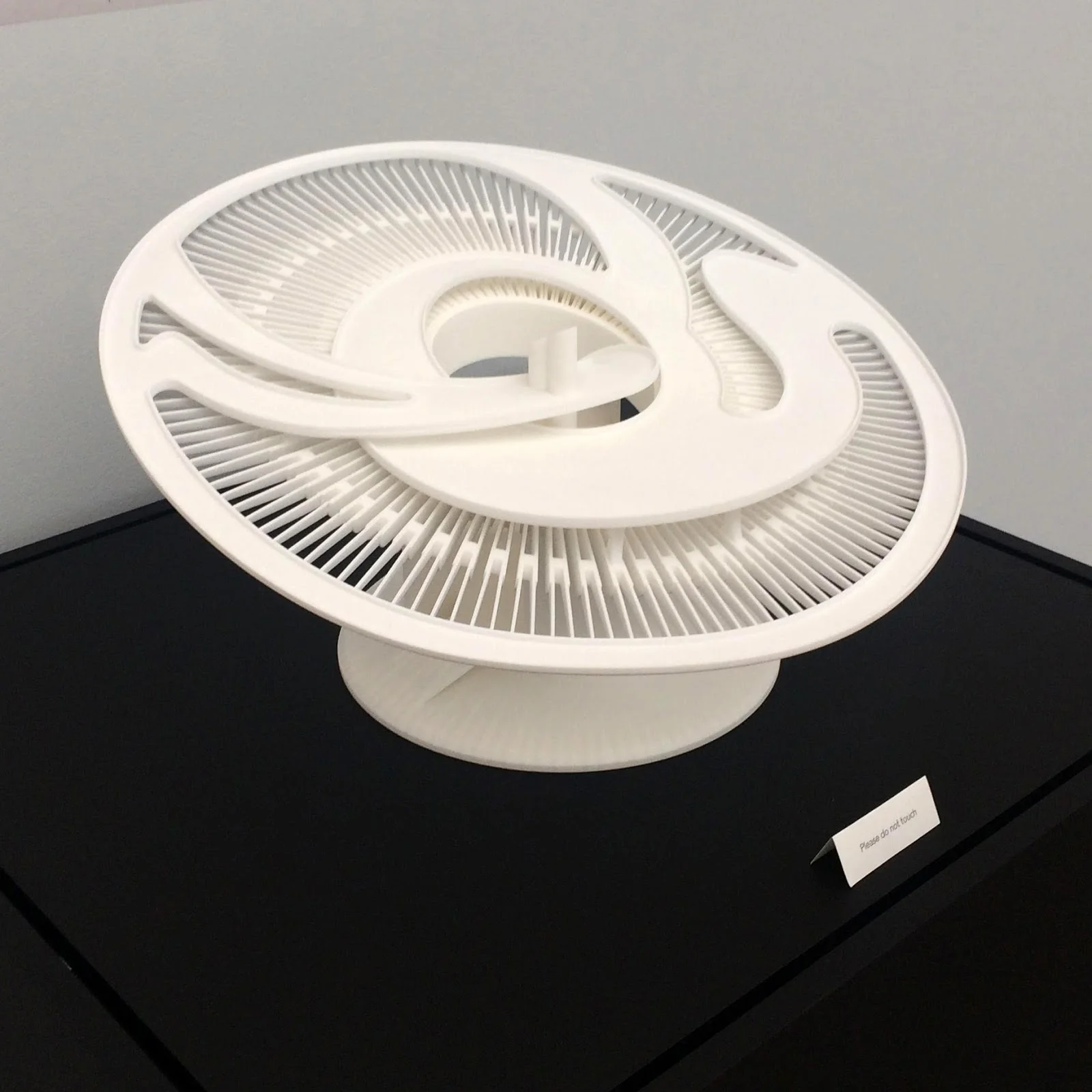

Paul Rudolph’s original project model for the Gatot Subroto project. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Mr. Wolff began researching the architect’s late designs for his upcoming book RUDOLPH :: RENAISSANCE Evaluating Paul Rudolph’s contributions to Architecture through his undiscovered late works until in-person activities were curtailed due to COVID-19. Not to be deterred, he began to recreate Rudolph's “unbuilt” designs as digital models.

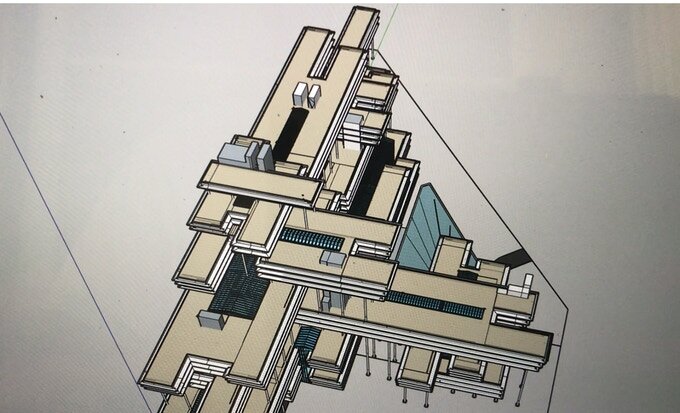

The Gatot Subroto model in progress. Image courtesy Eric Wolff.

According to Mr. Wolff,

“As part of my research I am digitally ‘building’ the Gatot Subroto based on drawings and models from Rudolph’s uncatalogued materials. I am working with a firm to render my digital ‘build’ into a life-like poster sized illustration of the building. We will render a scene with the building as seen from the street at dusk to emphasize the structure and fenestration. The output will be a large full-color poster illustration of the Gatot Subroto at dusk, which we will have professionally printed and available for donors. The illustration will later be used in the book and at events promoting the book.

To illustrate these designs an exciting collaboration with Design Distill was born. Design Distill is a multidisciplinary group that has the passion, talents and capabilities to translate my research of Paul Rudolph’s late works into visualizations, bringing the buildings to life so they can be evaluated and celebrated.

Rudolph’s buildings need to be experienced to be properly critiqued; making life-like illustrations will help viewers experience the buildings and interior spaces more completely. The digitization will help myself and other researchers study the structural and design elements intended by Rudolph. It will ”preserve” the buildings as they were intended to be built but with the ability to look at them in three dimensions and with the possibility of exporting the files for 3-D printing.

Importantly, the ‘eye candy’ of the buildings mask important contributions and innovations that Rudolph gave to the world of architecture, and through the rendering of his works his design principles can be further evaluated. This project will re-create the Gatot Subroto from blueprints, models and drawings and produce realistic renderings of the exterior, roof gardens and select interior spaces so they can be better understood and evaluated. The funding from this Kickstarter has been budgeted specifically for the work related to the Gatot Subroto.

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s mission includes supporting research about Mr. Rudolph’s architectural legacy and we are assisting Mr. Wolff’s kickstarter campaign as well as his future book.

We encourage you to help make this project a reality by going to the kickstarter link here and please share this project with your friends. Let’s see the Gatot Subroto project as Rudolph had intended!

PICASSO’S [SCULPTURE’S] COUSIN ?!? (and the RUDOLPH CONNECTION)

Picasso’s “Bust of Sylvette” sculpture in New York City’s Greenwich Village. Image courtesy of Art Nerd New York

Picasso’s sculpture—also named “Sylvette” —in Rotterdam. Image courtesy of Wikipedia, photo by K. Siereveld

AS WE WERE SAYING…

In a previous post we spoke about what we believed to be Paul Rudolph’s project for a visitors & arts center for the University of South Florida’s Tampa-area campus. It was to include a monumental concrete statue by Picasso—which, had it been constructed, would have been enormous: over 100 feet tall. Here is the perspective drawing for the proposed building, which shows the sculpture as part of the overall composition:

Rendering of the proposed visitors and arts center for the University of South Florida in Tampa. Picasso’s sculpture, which was to sit on the adjacent plaza, would have been a massive presence. Image courtesy of the USF Special Collection Library

What prompted us to explore this project is that visitors to the Modulightor Building in New York are intrigued by a Picasso sculpture which is on display within the building: a copy of the original maquette for that monumental sculpture:

Picasso’s maquette for the sculpture that was to go on the plaza of the University of South Florida. This authorized copy of the maquette is in the Modulightor Building in New York. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

That’s an authorized copy: Paul Rudolph obtained permission from Picasso to make it, because Rudolph admired Picasso’s sculpture so much.

In our earlier post, we’d given an art-biographical context these sculptures, noting other examples of Picasso’s work at monumental public scale. The prime example cited is his large work in New York City’s Greenwich Village: the concrete “Bust of Sylvette”:

Picasso’s Sylvette, in the midst of the I.M. Pei’s “Silver Towers” in NYC’s Greenwich Village. Image courtesy of Ephemeral New York

STILL, THEY’RE COUSINS…

Well, we’ve just heard about another sculpture by Picasso that we thought you’d like to know about—and this one has a similar title: “Sylvette”. It is located in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, and is in the city’s center, on a site on the Westersingel canal.

That ever-fascinating website, Atlas Obscura, has done a story about it (which drew our attention to the Rotterdam “Sylvette”), and it includes several photos showing the sculpture in its urban setting:

A screen grab from Atlas Obscura’s web page,showing the Picasso “Sylvette” in Rotterdam.

At the Sculpture International Rotterdam website, there are several pages on the sculpture, including a full essay, and also information on the various sites it has occupied in Rotterdam.

Is the Rotterdam sculpture a sister with the one in New York?

Cousins?

You decide!

Our Search for the Unknown (and 4 Newly Discovered Paul Rudolph Projects!)

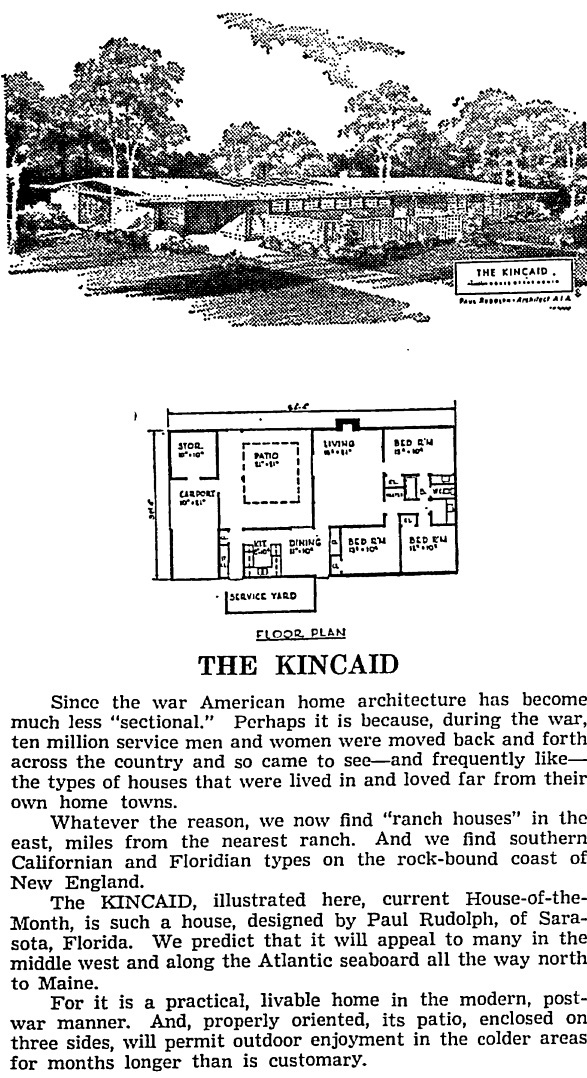

The “Kincade” is the name of a mid-1950’s house design by Paul Rudolph. It was published as a “Home-of-the-Month”—apparently part of a series of home designs available to the public through lumber yards and construction supply companies. This image is from a 1954 article in the Denton Journal.

WE HAVE A LITTLE LIST….

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation is making a complete record of all Rudolph’s projects—and currently there are over 300 projects on it. To the maximum extent possible—that is to say, findable—for each project we try to include comprehensive info: its exact location, names of all participants, budget, primary materials, drawings, pictures of models, construction photos, as-built photos…

BUT HISTORY IS HARD

You’ll notice that we said “currently”, for the list is still still growing. Now that may seem to be a strange thing to say about the work of an architect who passed away over 2 decades go: it’s not as though he’s kept creating more works that we need to keep track of. So it’s reasonable to assume and ask: Wouldn’t the record be complete by now?

Well, it’s not that simple.

Creating an accurate catalog of all of Paul Rudolph’s work, and finding the above-mentioned full range of data & images for each project, is a more challenging task than you might expect...

On the one hand:

Rudolph did not make it easy for us. Yes, he made his own official lists of commissions and projects—and those would appear in monographs, or be given to journalists or potential clients. Across a prolific career that lasted more than half-a-century, Rudolph kept editing those lists: adding new projects as they arose, and deleting ones which he considered less important. That’s a natural process for any architect—but some of the projects on those ever-evolving lists are just names to us, without barely any traces in books about him (or the hundreds of articles written about Rudolph.)

Here’s an example. One list includes “Dance Studio and Apartments” For that project, who was the client and what was the scope? All we presently know about that project is that it was from 1978, and was located somewhere in the Northeast. Was a design offered? If you look at our “Project Pages”—and we make one for each Rudolph project that we know of (the’re like our on-line file for each of Rudolph’s works)—you’ll find that some project pages are rich with information & images. But our page for the “Dance Studio and Apartment” is just a “place-holder”, currently containing only the most skeletal of info. We’d love to see some photos or drawings—but none have been found [yet.]

One prime source, for those researching Paul Rudolph, is the Library of Congress’ archive of Rudolph drawings & files: it runs to hundreds-of-thousands of items (all made before computers entered architectural offices—so they were drawn by-hand or typed). While there’s a general inventory, the only way to really know what’s in the archive is to go there and look—so we make repeated visits to Washington to do research within those rich holdings. [Perhaps, in one of those research trips, we’ll find out something on that “Dance Studio and Apartment.” ]

Sometimes we do have just a little info about a project—a single drawing—which makes us want to see more. For example: Rudolph had international commissions, including a few for Europe. A magazine showed a drawing for a house proposed for Cannes: the Pilsbury Residence. But that drawing is all we’ve ever come across about it. What was the project’s history? Was it built? We’re keen to find out.

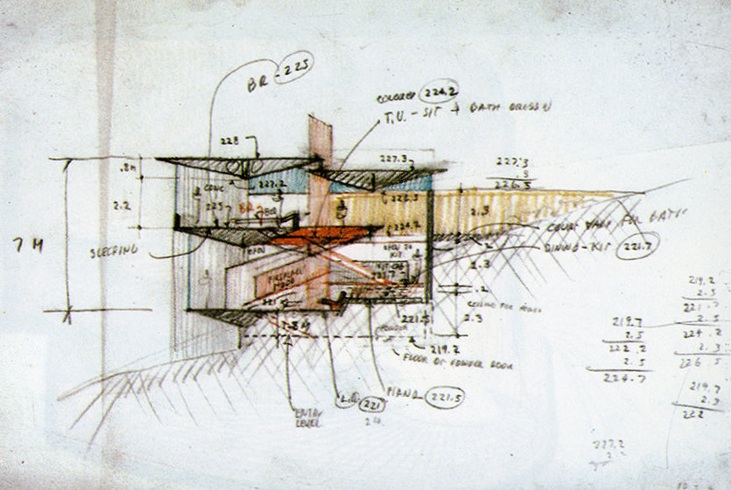

The Pilsbury Residence, a design from 1972. All we’ve seen—so far—of this project is this intriguing section sketch by Rudolph. It was published in a Japanese architecture magazine (in an issue entirely devoted to Rudolph’s work), and was designed for Cannes, France. It is one of Rudolph’s few works for Europe—N.B the dimensions seem to be in metric. The project’s name and proposed location is all that we know about it—so far. We’re hoping future research will reveal more. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Then there are the times when it is clear that something’s been built—but we know little else. For example: Rudolph was asked to design an office for a prominent Texan, Stanley Marsh III, and we’ve been able to find a single image of it for our project page—but, so far, that’s all we know.

The office of Stanley Marsh III—an interior Rudolph designed in Amarillo, Texas in 1980. Marsh (1938-2014) was quite a character, and—in his capacity as art patron—is most famous for commissioning the legendary art installation “Cadillac Ranch” by the art-design group, Ant Farm. Marsh also commissioned Rudolph to design a television station (also in Amarillo) that was constructed in the same year as the above office. Marsh was a great collector, as one can see in the works accumulated in this photo. But what was Paul Rudolph’s involvement in this office’s design? Modulightor—the lighting fixture company that Rudolph co-founded, and whose system of fixtures he designed—was started about the time of this project. So might the lighting system (seen on the office’s ceiling) be one that Rudolph planned and then specified from Modulightor? Are there other aspects of the office, not viewable in this shot, that Rudolph designed? More mysteries to be investigated!

Moreover, Rudolph was not the best record-keeper. Yes, his office [or rather, offices—as he started/re-started several, as his career took him around the country] had the sort of record-keeping systems which were standard for architectural offices in the post-World War II era of professional practice in the US. They maintained “time sheets” (or cards) to keep track of the hours that each staff member devoted to a project, as well as notes and files of various kinds were made (about meetings with clients, sketches, bids, construction field-reports, engineering, correspondence, etc..). But there was nothing like a company historian to keep a meticulous record of what was going on—and, going through the files, one gets the feeling that Rudolph was so busy that they just recorded (and kept the papers) of what was absolutely necessary to keep their various projects moving along.

A blank time card from from Paul Rudolph’s office—a fairly standard example of the type of record-keeping that would be used in architects offices in the US. Staff would fill these out to show how much time they’d devoted to each project, and submit them weekly. The resulting info would be used for billing. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

On the other hand:

Doing this research brings a continuous (and delightful) sense of adventure! As we come across new projects, images, and documents, we discover more layers of Paul Rudolph’s creativity—and also have an ever-enlarging sense the great range of design challenges with which he was willing to engage.

OUR FOUR LATEST DISCOVERIES: PREVIOUSLY UNKNOWN (OR “UNDER-DOCUMENTED”) RUDOLPH PROJECTS

In the last few weeks, we’ve come across 4 previously-unlisted projects—or ones with so little info (“under-documented) that they remain mysteries to be solved.

ONE: “KINCAID” HOUSE DESIGN

Newspaper articles from 1954 and 1955 show a house designed by Rudolph, the “Kincaid”. They were part of a series, the “House-of-the-Month”. These were a collections of house designs—often by skilled architects and well-thought-out, with good layouts, and planned for efficient construction. They were offered to the public via advertisements and books. Such books, which usually showed a dozen-or-more different designs (of various styles, sizes, and budgets) were available at lumber yards, building-supply stores, and newsstands. The info on each house design usually included a perspective rendering, floor plans, basic data, and a brief written description—and every house received a name. If one liked a house, complete plans & specifications could be ordered for a modest fee.

An example of a House-of-the-Month book: a collection, in booklet form, of available architectural designs for houses.”by leading architects.” A quarterly publication of the Monthly Small House Club, Inc,, this one is from 1951 (a few years before Rudolph’s “Kincaid” house came out.)

While, via this system, an architect did not get to make a custom solution for a client, he was able to exercise his creative ability to design a workable, affordably house that had a sense of style—and enough generic good qualities that it might appeal to multiple clients. So the advantage for the architect was that he might be rewarded with many small fees for the same design [Or perhaps he received a flat-fee from the publisher? Arrangements may have varied.] Such “plans service” companies continued to exist for decades—and even have a recent incarnation in the Katrina Cottages—and their impact on the American housing market would make an interesting study. Evidently, as shown by the “Kincaid,” Rudolph participated in this system—though on what terms (or what he ultimately thought of it) remains a mystery.

TWO: DANCE STUDIO AND OFFICES IN FORT WORTH

The May/June 1998 issue of Texas Architect ran an article surveying the work that Rudolph had done in Texas. Max Gunderson’s text reviews the origin and history of each project.

Texas Architect has been published since 1950, and you can access its full archive of back issues at their website. It was the above issue that included Max Gunderson’s excellent article surveying Rudolph’s work in that state.

In the course of speaking about one of Rudolph’s most splendid house designs—the Bass Residence in Fort Worth—he also mentions:

Rudolph would also design the Fort Worth School of Ballet for Anne Bass, a simple teaching/workspace and offices in a retail strip.

Since a great architect can bring “an extra something” to even the simplest projects, we’d love to see what Rudolph came up with here.

THREE: BAHRAIN NATIONAL CULTURAL CENTER

We’ve heard that Rudolph was involved in a project to design a cultural center for Bahrain. This may have been as part of a design competition. There’s a transcript of an oral history interview with Lawrence B. Anderson (1906-1994): he was an architect who was already well familiar with Rudolph—his firm was the associate architect, with Paul Rudolph, for the Jewett Arts Center at Wellesley (and that transcript has interesting things to say about that project.) Anderson participated in a 1976 jury to review the proposed designs for the Bahrain National Cultural Center, and in the transcript he speaks of the process and cultural context—but he doesn’t name the competitors or winners. So we don’t have a confirmation—at least from that one source—as to whether Rudolph was a competitor (of if he “placed”). We’d like to know more about this project—and, of course, we will welcome any “leads” that our readers submit.

By-the-way: it’s worth noting that, across his half-century career, Rudolph was involved in several projects for the mid-east. Among them: a US embassy for Jordan, a sports stadium for Saudi Arabia, and an apartment-hotel in Israel—none of which, unfortunately, reached construction stage.

FOUR: HUNTS POINT MARKET, NEW YORK CITY

Hunts Point Market (or, more formally, the Hunts Point Cooperative Market), in New York’s borough of the Bronx, is one of the the largest wholesale food markets int the world—and a large portion of the food (produce, meat, and fish) consumed in the New York City metropolitan area is provided through it. Occupying 60 acres in the Hunts Point neighborhood, and it's annual revenues exceed $2 billion.

During the administration of NYC Mayor Robert F. Wagner, market facilities were constructed in 1962: a 40-acre facility with six buildings—and now the Market consists of seven large refrigerated/freezer buildings on 60 acres.

New York City Mayor Robert F. Wagner and U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman look at architect's drawing of new Hunts Point Market during the 1962 ground breaking ceremonies in the Bronx, NYC. The year of this image, and the fact that Wagner was New York City’s mayor just prior to Mayor John V. Lindsay, suggests that the design shown is the market that was built prior to the announcement that Rudolph would become involved. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

But it seems that during the administration of the next mayor (John V. Lindsay), it was planned that Paul Rudolph was to have some involvement in further development of the Hunts Point market facilities. At least that’s what a document, from the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, seems to indicate. We’ve found a press release from the Office of the Mayor, dated May 2, 1967, in which Lindsay appoints Rudolph

“… as supervising architect for the Hunts Point food processing and distribution center. Mr. Rudolph will be responsible for the project design, for designing many of the market buildings in the project and setting all design and structural specifications for the development.”

Most of the rest of the press release praises Rudolph, and says nice things about the importance of the Hunts Point market and its location. But there’s not much more about the nature of the project, except the text again refers to food “processing”—so the new buildings, which Rudolph was to work on, might likely have accommodated facilities for the transformation of food (as distinct from marketing/distribution).

Lindsay was mayor during one of the city’s (and nation’s) most exciting and also most difficult periods, with his administration lasting from 1966-1973.. He is often evaluated as a a "good guy” with positive ideals, but one who was up against the tumultuous churnings of in NYC’s/country’s politics, economy, and culture in those tough and “crazy” years of the late 60’s-to-early-’70’s. This was richly shown in a 2010 exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York, as well as the accompanying book.

It was NYC mayor John V. Lindsay who announced that Rudolph would be involved in the Hunts Point Market. Many aspects of the exciting and difficult years of his administration were on display in a 2010 exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York, for which this was accompanying book.

Lindsay’s administration did have a number of innovative construction initiatives (preponderantly in housing)—and this Hunts Point project might have been one of them.

The further evidence of Rudolph’s involvement is an item in the archives of the Library of Congress: a photos of a rendering of the old (1962) market design, with some markings on it—and the Library’s notes say that it was donated by “Rudolph Assoc., Architects”. Below is a small image of it. We’d guess that means it came into their possession as part of the large body of Paul Rudolph material that he donated to them—but that’s only a reasonable surmise.

So this is another example of a project that deserves further research. Did Rudolph produce a planning study and designs for it? Why did it not go forward? We’ve heard that there’s an archive of papers related to the Lindsay years: perhaps they’ll have some further information? We’ll let you know if we find anything.

A tiny image, from the Library of Congress, found when researching the Hunts Point project. It appears to be the same architect’s rendering (not by Rudolph) as shown in the photo above, but with some additional marks on it. What makes it intriguing is that the library’s info on this print says that it was contributed by “Rudolph Assoc.” Image courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

WANTED: HISTORY DETECTIVES & TREASURE HUNTERS

If you love mysteries, and would like to help us learn more about these projects, we’d welcome your help!

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation is always looking for volunteers—including those who’d enjoy tracking-down information on Rudolph’s “under-documented” projects (like these—but there numerous others). Or perhaps you know something about the above-mentioned projects, and would be willing to share that info with us.

We’re seeking to build an archive & database that students, scholars, building owners, designers, and journalists will really find useful—and your help on these research projects would be welcome! You can always reach us through:

Celebrating NATIONAL AVIATION WEEK - with Paul Rudolph !

A comprehensive designer is interested in (and interested in designing) Everything! Here are two scenes from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City proposal—these showing examples of his flying saucer-esque personal helicopters, as well as his curious and intriguing designs for various types of roadsters and ships. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

National Aviation Week got off to a flying start on August 19th—and who better to celebrate it with than Paul Rudolph!

But hold on. Other architects have clear connections with flight. Eero Saarinen, Helmut Jahn, Minoru Yamasaki, I.M. Pei, and SOM (and, most recently, Zaha Hadid) designed some great Modern airport terminals. And Le Corbusier and Wright included aviation imagery (and fantasy) into their manifestos and projections of future living.

Le Corbusier even write a whole book expressing his delight in flight and aircraft—and used them as a symbol for forward-looking thought as well as aesthetics. His book, “Aircraft” came out in 1935, Image courtesy of Irving Zucker Art Books.

Other futurists incorporated airships into inventive notions of how constrution would proceed in days to come, as in this example from Buckminster Fuller:

This is one of Buckminster Fuller’s many inventive ideas of how we could live and build in the future. He envisioned an airship delivering one of his apartment houses—so efficiently designed that the fully constructed building was light-enough to lift by dirigible—to the site. But the building would be lowered into its foundation only after the ship first dropped an explosive charge to make the hole!

Rudolph never completed an airport. But he certainly did propose one—and it was a design with strong architectural character and inventive ideas.

Paul Rudolph: The Florida Houses, by Christopher Domin and Christopher King, is an indispensable resource for learning about the first phase of Rudolph’s career. Although the book focuses on his residential designs—the preponderance of the commissions Rudolph was receiving then—it also includes his work on other building types: schools, restaurants, beach clubs, an office building—and an airport.

Rudolph’s site plan , from the mid=1950’s, for a proposed new terminal for the Sarasota-Bradenton Airport in Florida. His terminal building is at the left side of the drawing. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

According to Domin’s and King’s book, Rudolph’s proposed terminal would have replaced a “primitive” existing structure, and the new building would have included “…an air traffic control tower, overnight accommodations, eating facilities, and a large swimming pool to accommodate the weary traveler.” Moreover, according to an Architectural Record article of February 1957, “The qualities of lightness and precision felt necessary to an airport have been sought throughout.”—and this was conveyed by the use of open web columns and trusses.

The building, as designed, did not proceed due to budgetary issues—but we can still see that Rudolph was as inspired by aviation as many of the other master architects of his age. So let’s celebrate National Aviation Week with a toast to Paul Rudolph’s aerial aspirations!

An aerial view of the proposed terminal (dramatically drawn in 3 point perspective—a rare technique for Rudolph, or any architect). In this rendering, originally published in Architectural Record, the roof is lifted off in order to reveal the various functional areas of the building. Toward the front is a rather sizable swimming pool (as signaled by the diving board)—a nearly-unknown feature for any airport (but one that might have fit unusually well for this building’s Florida setting). Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Rudolph’s rendering of the inside of the main concourse. The double-height space is supported by the kind of trussed structures whose forms were associated with airplane construction—-the high-tech of its time. Yet there are pure architectural grace-notes, like the grand spiraling stair seen at the far-right end of the space, which connects the main floor with the upper galleries. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

An exterior side elevation of the terminal building. The capsule-like control tower [another saucer?—perhaps Rudolph saw Wright’s renderings?] is in the background at the right. The building’s columns appear to flare outward at their tops: a form reminiscent of the profile of ancient Minoan columns—and a silhouette that would be seen in later architectural works—from Rudolph to Nervi to Leon Krier. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Paul Rudolph’s rendering for the Greeley Memorial Laboratory for the Yale Forestry School—a building, on the Yale Campus, which he designed within a couple of years of his proposal for the Florida airport. While the columns at Greeley were of precast concrete (with mathematically-derived sculptural curves), their overall silhouette is reminiscent of the tops of the columns at for the airport—so might it be that the airport terminal project was where those forms germinated? Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

RUDOLPH’S FIRST DESIGN?

An illustration from the cover of a 1938 issue of “The Plainsman”, the official student newspaper of the Alabama Technical Institute (now: Auburn University). Could this be Paul Rudolph’s first published design? Image from an original newspaper clipping in the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

BEFORE YALE AND BEFORE HARVARD: ALABAMA!

When it comes to educational institutions, Paul Rudolph is most strongly associated with Yale, where he was chair of the architecture department from 1958 -to- 1965 (a good, long run for any chair or dean). If we were to think about his educational involvements a bit further, one would focus on Harvard: there he received his Master’s degree, studying during a period when Walter Gropius (1883-1969) was in charge of the architecture program.

A studio project by Paul Rudolph, made while he was completing his Masters degree in Harvard’s architecture program, then under the direction of Walter Gropius. The house was to be sited in Siesta Key, FL, and was known as “Weekend House for an Architect” (and was later transformed into his design for the Finney Guest House project.)

Image courtesy of Harvard student work archives.

But where did Rudolph’s architectural eduction actually begin? There’s abundant evidence that he was interested in architecture, design, and art from an early age (in addition to a youthful involvement with music—which also became a life-long focus). A letter from his mother recounts his boyhood explorations in design. And Rudolph’s own memory, about his first experience of a Frank Lloyd Wright building (at about age 13) testifies to the impression that it made on him.

His formal education commenced at the Alabama Technical Institute—now known as Auburn University. It was a traditionally-oriented architecture program, but the students were also made aware of Modern developments. By all accounts, Rudolph excelled—and we have his grade report for the first semester of 1939-1940:

Rudolph’s highest grades show his great focus on design—and music.

Document is from the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

HIS FIRST DESIGN?

Among the other documents in the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation is a clipping from The Plainsman—then and now, the school’s official student newspaper. The article, from February 9, 1938, shows a pen-and-ink rendering of a proposed campus gateway, and the caption says the the Senior Class of ’38 may fund it.

What’s intriguing to us is the signature on the drawing: Rudolph

The caption confirms the authorship, saying “Drawing by Paul Rudolph”—and combined with the fact that Rudolph had held onto the clipping for decades (whence its origin in our archives) connects him firmly to the drawing.

The rendering, tantalizingly, is signed by Rudolph—but is it his design?

For a while, it looked like the project was going forward. An follow-up article in the February 23rd issue of The Plainsman showed the same rendering, and reported:

SENIORS APPROVE MAIN GATE

Proposed Gateway: Construction work upon the Senior Main Gate, for which the senior class showed a decided preference in the election last Wednesday, will begin as soon as the architect in charge has completed the exact plans and specifications for its building. It will be situated at the South-East corner of the campus across from the “Y” Hut. But a subsequent story, exactly one month later, reported that the project had been “dropped”—the explanation being that the projected cost far outstripped the original rough estimates, and “… no gate worthy of the class or the school could be constructed with the money appropriated.”

The gate remains, to our knowledge, unbuilt. But beyond these few facts, the mysteries of history begin, and we wonder:

Did Rudolph create that design? The caption says “Drawing by…”, but does not make clear the authorship of the design.

If it was his design, was the gate a project assigned to his class, with Rudolph’s scheme the one that stood-out among his classmates (and hence was chosen)?

Or was it the design by someone else—perhaps one of the professors or a local professional—and Rudolph only did the rendering?

If the latter, was the rendering done as a course project—perhaps an exercise in perspective rendering?—or did he volunteer, or was this a freelance project?

The second article about the project, quoted above, mentions “the architect in charge”—but who was that, and what was their relation to the design in the rendering? Could it have been a local firm (which handled the school’s routine work)—but the design was Rudolph’s

All tantalizing questions—but where or how could one find any convincing answers? The facts may be hidden in a diary, or stray letter—or nowhere. We may hope for some later revelation, for some illuminating document that comes to light—and things are sometimes found—but we must face the fact there are many more cases where history will never reveal her secrets.

RUDOLPH DID BUILD AT AUBURN

Paul Rudolph did eventually build at his old school: he designed the Kappa Sigma Fraternity House (the society to which he belonged as a student)—a frank, Modern design, from the early 1960’s.

Time passed and the building, after years of service, no longer fit the needs of the fraternity. They wrote to Rudolph, asking if he’d engage in a renovation—but, according to a letter in our archives, he told them that it would be better if they worked with someone locally. This brings up another mystery: Rudolph worked all over the country, indeed, internationally—and he was not un-used to being asked to come back and do alterations or changes on his already-built designs. So why would the distance from his office to Alabama present any difficulty? We’ll probably never know his reasons for the rebuff.

After Rudolph’s passing, Preston Philips—an architect who had gone onto a distinguished career, after having worked for Rudolph—visited the building. According to his April 25, 2007 letter in the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation archives, he reported that the fraternity had abandoned the it several years before, and the building was owned by the University. It stood empty and “in desperate condition”—though “largely intact”, and “beautifully sited in a Pine grove on a large corner site.” However, water was intruding due to some roof and glazing problems. Mr. Philips hoped that the University might find another use for the building and renovate, possibly as a guest house for visiting dignitaries and a place for dinners and receptions—but he was fearful that without some quick action, the building could be lost.

Regrettably, the building was demolished in 2016.

The Kappa Sigma Fraternity House at Auburn University, Auburn, AL. Paul Rudolph, architect.

Photograph: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Paul Rudolph and Circular Delight

Image: cargocollective.com

FAMILIAR FORMS

When one thinks of an architect, naturally one visualizes their most famous buildings - but, as much a part of that imaging process are the forms & shapes which you primarily associate with their work.

Thus, entrained with any thought of Wright, are the forms of his thrusting/cantilevered horizontal planes, counterpointed by solid masonry masses, his rhythmic verticals, and rigorous-but-playful use of circles. For Mies, it might be his floating, shifting planes (as in the Barcelona Pavilion), his cruciform column (from the same project), and his glazed grids. Corb is associated with a big vocabulary of forms—and strongly with his more sculptural shapes (like at Notre Dame du Haut) or, conversely, his platonically geometric “purism” (as in his Villa Stein or Villa Savoye).

A photo and plan-detail drawing of Mies van der Rohe’s “cruciform column”, as used in his 1929 Barcelona Pavilion. Image: www.eng-tips.com

CURVILINEAR CONCEPTIONS

When it comes to forms, there’s something inherently pleasurable in curves and circles—one wonders if we, unconsciously, relate it to the pleasures and vitality of human bodies - or life itself. And it’s useful to recall that the education of all artists (and architects) - at least ‘till recently - included figure drawing.

With Rudolph, one doesn’t often think of circles, but he was hardly allergic to using curves in his work. They show up, sometimes most effusively, several times in his oeuvre. An example would be one of his most famous designs: the Healy Guest House:

Paul Rudolph’s perspective rendering of the Healy Guest House (also known at the “Cocoon House”), with its suspended, catenary curve roof. It was built in Siesta Key, Florida. Image: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Or in this baroquely sensuous set of stairs:

A staircase in Paul Rudolph’s Government Service Center in Boston. Photo: NCSU Libraries

Or his intriguing proposal for the Inter-American Center:

Rudolph’s design for the bazaar-market building, part of the Inter-American Center (also known as the Interama) project, which was envisioned for the Miami area of Florida. Image: Library of Congress

There are other projects of his where flowing curves show up, but we’ll end with Rudolph’s own NYC apartment: its modest-size living room was enhanced by the floating curves of hanging bookshelves which surrounded the space:

Sinuously curved suspended shelving provided space for book storage and display, in Rudolph’s own NYC apartment. Photo: Tom Yee for House and Garden

CIRCLING BACK TO WRIGHT

But what about circles in Rudolph’s work?

For that, we need to return to Wright. The two great influences which are often cited for Rudolph are Wright and Le Corbusier. Wright - for his richly layered, deep-perspective spaces; and Corbusier - for the bold, sculptural plasticity of (especially) his later works. With Wright, we know the connection is not spurious, for we have a photograph of the youthful Rudolph visiting a Wright-designed home:

Rudolph (at left) and family members, visiting Wright’s Rosenbaum House in Alabama.

Photo: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Now here’s where it gets really interesting. This is the overall plan for Rudolph’s “Floating Islands” project of 1952-1953:

Rudolph’s drawing for the Floating Islands project, for Leesburg, Florida. Image: Library of Congress

This is Interiors magazine’s description of the project:

"Architect Paul Rudolph intends to enliven one 180-mile stretch in the interior - between two of Florida’s most popular sights, Silver Springs and the Bok Tower - with an amusement center and tourist attraction where the main feature is Florida flora growing from earth materials supported by masses of floating roots commonly called ‘floating islands.’ The site has a 1000-foot frontage on two U.S. highways and easy access to a fresh water lake where fishing is excellent. Aimed primarily for sight-seers who want to stop for a couple of hours for food and rest to learn something fast about Florida flora, the center would provide a restaurant near the road for passing motorists as wells as those who stop to see the gardens. For entertainment and recreation there will be a variety of exotic floral displays, grandstand shows of swimming and diving, and boating and water skiing on the lagoon which leads to the large lake and then a string of lakes and canals for boat excursions."

From: "Baroque Formality in a Florida Tourist Attraction" Interiors magazine, January, 1954

When contemplating this composition, what immediately to mind are Wright’s designs that utilize circles, especially decorative designs, like this:

Frieze over the fireplace in the living room of the Wright-designed Hollyhock House, in Los Angeles, California. Image: Architectural Digest

Or this Wright design of a rug at the David and Gladys Wright house (incidentally, this house is one of our favorites) -

Image: Los Angeles Modern Auctions

And here is Wright himself, contemplating one of his most famous graphics, “March Balloons”:

Frank Lloyd Wright (photographed circa the 1950’s) looking at a design he’d submitted for Liberty Magazine in the 1920’s. Image: www.franklloydwright.org

Now, looking at these Wright designs, and looking at Rudolph’s plan for the “Floating Islands” project, do you see some formal resonance? Maybe a lot? We do. Hmmmmm!

But -

Isn’t history fascinatingly - for we learn that Wright had, earlier, worked on this project! Here’s what Christopher Domin and Joseph King tell us, in their wonderful book on Rudolph’s early work:

“Frank Lloyd Wright designed a sprawling scheme for this project in early 1952, which contained a central pavilion with a distinctive vaulted plywood tower, a series of cottages, and two pier-like motels with access from each room. After this project came in substantially over budget, Rudolph was brought in to reconceptualize the program and master plan for this combination highway rest stop, and tourist attraction near Leesburg in central Florida.”

Practical, budgetary, and programmatic challenges aside, one wonders what Rudolph thought (and felt!), knowing that he was supplanting the great Master himself. These fine historians go on to venture that Rudolph, in his design, might have been referencing Wright’s work (and mention several formally pertinent projects of Wright’s.) Or perhaps Wright’s original plan for this development was so strong, that Rudolph felt it provided a good and relevant parti for his own design? These are questions for which it is interesting to speculate - though they too have a circular quality.

PLATONIC PLEASURE

We were prompted to these rotund reflections by coming across this project, by the ever-fascinating MZ Architects:

Image: MZ Architects

It is their “Ring House”, a residential design for Riyadh. MZ describes it as:

“The proposed building consists of a cylindrical volume embracing a rectangular one. The cylinder acts as a protective closed wall with a single narrow opening serving as the entrance, while the inside rectangle accommodates fluidly all the house functions necessary for the everyday life of the artist: a bedroom, a bathroom, a living room, a kitchen and an atelier. The interior space interacts smoothly with the serene outdoor atrium, a large terrace garden with one symbolic tree and a circular water feature. By means of this composition, the ring-shaped structure figuratively resembles a cocoon ensuring a sense of intimacy and calmness for the house, that closes itself completely from the surroundings.”

The renderings make it look like the house, the courtyards, and the perimeter wall are made of concrete—and, if that’s the intention, this is certainly one of the most serenely elegant uses of concrete we’ve ever come across. MZ has other renderings for this superbly composed project—and we suggest you visit their website to see them (as well as explore the rest of their interesting oeuvre).

And that about rounds-out things for today…

Paul Rudolph: Designs for Feed and Speed

Front view of a model of a drive-in: the Cantor “HIWAY” restaurant, designed by Mies Van der Rohe. Image: The Museum of Modern Art

Floor plan and elevation of a drive-in: the Cantor “HIWAY” restaurant, designed by Mies Van der Rohe, pencil on tracing paper, circa 1945-1950. Image: The Museum of Modern Art

HIGH DESIGN FOR THE EVERYDAY

Famous architects—those operating at the very highest level of architecture-as-art - have designed for some surprising prosaic uses. Above is a model, plan, and elevation for Mies’ design for a highway drive-in. And did you know that he also - and we’re not kidding - did an ice-cream stand in Berlin? (Yes, it got built.)

Frank Lloyd Wright designed a gas station - which also was built:

Wright’s gas station, located in Cloquet, Minnesota. Image: McGhiever

Wright also designed a dog-house. And here’s a fascinating one designed by Philip Johnson, which is against a stone retaining wall near Johnson’s Glass House:

A Philip Johnson designed dog house—on the Glass House estate. Image: www.urbandognyc.com

By-the way, Rudolph said he’d be willing to design a dog house - if - he was allowed to design a very good and unique one. (We’re sure it would have been fascinating - but, as far as we know, he was never commissioned to do so.)

And, of course, famous architects have designed objects for everyday use - particularly furniture. We all know Mies’, Breuer’s, and Le Corbusier’s chairs, but what about Aalto’s tea cart - a very elegant design:

Alvar Aalto’s Tea Trolley 901, a design from 1936—and still manufactured and available. Image: www.Aalto.com

AND RUDOLPH DOES AS WELL

So it is no wonder that Paul Rudolph, when asked to design a donut stand, engaged in the project. Here is his perspective rendering, from 1956:

Paul Rudolph’s perspective rendering of a donut stand for Tampa, Florida. Image: Library of Congress

If one divided the arc of Rudolph’s career into geographically-based chapters (around the locations of his primary offices), one would say that he had three phases:

Florida (approx. just after WWII -to- 1958)

New Haven (approx. 1958-1965)

New York (approx.. 1965-his passing in 1997)

This project happened during the time his primary office was in Florida, and the preponderance of his clients in that state. It was there, centered in the Sarasota area (though extending outward to the rest of the state and beyond) that Rudolph started his career. Initially he was doing small houses, guest houses, beach houses… but his practice eventually grew to embrace all kinds of building types, from primary residences to schools, offices, and larger developments.

Rudolph’s designs for Florida are among his most creative and fascinating bodies of work. For a long time, one could only learn about them via delving into vintage professional journals—but an exceptionally fine book, covering that period, came out in 2002:

Image: Amazon.com

Paul Rudolph: The Florida Houses

by Christopher Domin and Joseph King, with photographs by Ezra Stoller. Published by Princeton Architectural Press

The book’s title undersells the book it bit, for (we’re happy to say) that the volume covers more than houses. For example: this donut stand. About it, they write:

"Rudolph, along with Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe, believed that even the most banal aspects of the American popular landscape such as fast-food restaurants and gas stations were worthy of an architect’s services. The Donut Stand, designed for a group of investors in Tampa, was commissioned as a prototype building to act as the marketing symbol for this roadside business. Rudolph hung a thin planar structure from four vertical steel supports, creating a veritable floating roof with a minimal, glass-enclosed interior space below. This project was designed in the Cambridge office at the same time as the Grand Rapids Homestyle Residence, with a similarly conceptualized open plan and restrained use of materials. A hastily rendered design drawing was presented to some of the investors, but was soon shelved after a payment dispute. By this time Rudolph opened his Cambridge, Massachusetts office to develop drawings for the Jewett Arts Center in Wellesley and later the Blue Cross Blue Shield Building in Boston, but many Florida projects from this period were also coordinated from this satellite studio."

Like dating a project - always a challenge in architectural history - the location where this project was done poses similar questions. As the authors point out above, when it comes to where this was designed, the story is a bit more complicated than the Florida-New Haven-New York triad.

At various times in his career, Rudolph had temporary satellite offices. (We tried to lay this out when we put together a timeline for the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s recent exhibit, Paul Rudolph: The Personal Laboratory - and found that it was challenging to figure-out the many locations where Rudolph and his team(s) worked.)

Even so, it is also hard to say that something was designed in one particular spot: architects are thinking/sketching/pondering design problems wherever they go. The documentary about Rudolph, “Spaces: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph” shows him sketching on the train. So even if the presentation materials for this donut stand were done in Cambridge, you can well guess that the place(s) where Rudolph was thinking about it was not geographically limited.

This was not Paul Rudolph’s first foray into roadside food facilities! The Library of Congress’ collection of Rudolph drawings also has a Tastee Freez stand, which he designed a few years before:

Paul Rudolph’s perspective rendering of a Tastee Freez stand, from 1954. Judging from the palm trees (in the background of the drawing), this too was for Florida. Image: Library of Congress

It’s interesting to contemplate what unites the two designs - and how they fit into Rudolph’s work and thinking. A few primary points might be mentioned:

The articulation of structure - as distinct from the planes of the roof/wall/enclosure/signage.

The play of opaque and transparent - which is strongly expressed in the graphic (solid black) contrast of the dark underside of the roof-planes.

The attention-getting nature of the design - even when done in a strictly High-Modern style, both buildings are well-planned to be noticeable from speedy passing traffic.

The inclusion of shade - especially important in a semi-tropical environment like Florida.

Never forgetting the human - both renderings include figures and seating which give a clear sense of scale (as well as conveying that these are not just abstract compositions, but rather for real use.)

Bauhaus-ian composition - which is hardly to be wondered-at, as Walter Gropius—founding director of the Bauhaus - was Paul Rudolph’s teacher when in Rudolph was in graduate school at Harvard.

High (end) or low; fast food or elegant settings; at intimate or gigantic scale - Rudolph, like any true design-master, could engage interestingly with any project.

The Seagram Building - by Rudolph?

The Seagram Building in New York City, under construction, designed by Mies van der Rohe. Photo: ReseachGate, Hunt, 1958

Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building is one of the loftiest of the high icons of Modernism. For decades, it was almost a sacred object. Indeed, several of his buildings - the Barcelona Pavilion and the Farnsworth House (as well as the Seagram) - were maintained in a bubble of architectural adoration.

Is reverence for Mies going too far? Actually, it’s architect Craig Ellwood at Mies van der Rohe’s National Gallery museum building in Berlin (caught while photographing a sculpture.) Photo: Architectural Forum, November 1968

SEEMS INEVITABLE

Mies is considered to be one of the triad of architects (with Wright and Corb) who were the makers of Modern architecture - a holy trinity! Given Mies’ fame - and the quietly assured, elegantly tailored, serenely-strong presence of Seagram (much like Mies himself) - it seems completely inevitable that he would be its architect. Like an inescapable manifestation of the Zeitgeist, it is hard to conceive that there might have been an alternative to Mies being Seagram’s architect.

Mies is watching! Photo: The Charnel House – www.charnelhouse.org

BUT WAS IT?

In retrospect, seeing the full arc of Mies’ career and reputation, it does seem inevitable. Whom else could deliver such a project? A bronze immensity, planned, detailed and constructed with the care of a jeweler.

But - as usual - the historical truth is more complex and messy (and more interesting).

GETTING ON THE LIST(S)

Several times, Phyllis Lambert has addressed the history of the Seagram Building and her key role in its formation. But the story is conveyed most articulately and fully in her book, Building Seagram—a richly-told & illustrated, first-person account of the making of the this icon, published by Yale University Press.

Phyllis Lambert’s fascinating book on the creation and construction of the Seagram Building. Image: Yale University Press

Part of the story is her search for who would be the right architect for the building. In one of the book’s most fascinating passages, she recounts the lists that were made of prospective architects:

“In the early days of my search, I met Eero Saarinen at Philip Johnson’s Glass House in Connecticut. In inveterate list-maker, he was most helpful in proposing what we draw up a list of architects according to three categories: those who could but shouldn’t, those who should but couldn’t, and those who could and should. Those who could but shouldn’t were on Bankers Trust Company list of February 1952, including the unimaginative Harrison & Abramovitz and the work of Skidmore , Owings & Merrill, which Johnson and Saarinen considered to be an uninspired reprise of the Bauhaus. Those who should but couldn’t were the younger architects, none of whom had worked on large buildings: Marcel Breuer, who had taught at the Bauhaus and then immigrated to the United States to teach with Gropius at Harvard, and, as already noted, had completed Sarah Lawrence College Art Center in Bronxville; Paul Rudolph, who had received the AIA Award of Merit in 1950 for his Healy Beach Cottage in Sarasota, Florida; Minoru Yamasaki, whose first major public building , the thin-shell vaulted-roof passenger terminal at Lambert-Saint Louis International Airport, was completed in 1956; and I. M. Pei, who had worked with Breuer and Gropius at Harvard and became developer William Zeckendorf’s captive architect. Pei’s intricate, plaid-patterned curtain wall for Denver’s first skyscraper at Mile High Center was then under construction.

The list of those who could and should was short: Le Corbusier and Mies were the only real contenders. Wright was there-but-not-there: he belonged to another world. By reputation, founder and architect of the Bauhaus Walter Gropius should have been on this list, but in design, he always relied on others, and his recent Harvard Graduate Center was less than convincing. Unnamed at that meeting were Saarinen and Johnson themselves, who essentially belonged to the “could but shouldn’t” category.”

WHAT IF’S

So Rudolph was on the list and considered, if briefly. Even that’s something—a real acknowledgment of his up-and-coming talent.

Moreover, Paul Rudolph did have towering aspirations. In Timothy Rohan’s magisterial study of Rudolph (also published by Yale University Press) he writes:

“Rudolph had great expectations when he resigned from Yale and moved to New York in 1965. He told friends and students that he was at last going to become a ‘skyscraper architect,’ a life-long dream.”

That relocation, from New Haven to New York City, took place in the middle of the 1960’s—about a decade after Mies started work on Seagram. But, back about the time that Mies commenced his project, Rudolph also entered into his own skyscraper project: the Blue Cross / Blue Shield Building in Boston.

Paul Rudolph’s first large office building, a 12 storey tower he designed for Blue Cross/Blue Shield from 1957-1960. It is located at 133 Federal Street in Boston. Photo: Campaignoutsider.com

It takes a very different approach to skyscraper design, particularly with regard to the perimeter wall: Rudolph’s design is highly articulated, what Timothy Rohan calls a “challenge” to the curtain wall (of the type with which Mies is associated)—indeed, “muscular” would be an appropriate characterization. Moreover, Rudolph integrated mechanical systems into the wall system in an innovative way.

A closer view of the Blue Cross/Blue Shield’s highly articulated façade and corner, seen nearer to street-level. Photo: Courtesy of the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Library

And, Rudolph did end up fulfilling his post-Yale desire to become a “skyscraper architect”—at least in part. He ended up doing significantly large office buildings and apartment towers: in Fort Worth, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, and Jakarta. Each project showed him able to work with a variety of skyscraper wall-types, materials, and formal vocabularies. Rudolph, while maintaining the integrity of his architectural visions, also could be versatile.

And yet -

He was on that Seagram list, and we are left with some tantalizing “What if’s…

What if he had gotten the commission for Seagram—an what would he have done with it?

Paul Rudolph's Futuristic Vision: The Galaxon

Rendering of Paul Rudolph’s ‘Galaxon’. Image: Shimahara Illustration

VISIONS OF THE FUTURE

There are not many phrases more evocative than “THE FUTURE”. Whether in joyous expectation or fear (of a mixture of both), imagining, predicting, envisioning, and forecasting The Future has been one of humanity’s longest obsessions - and indeed, many religious and social practices, going back to the most ancient of times, are concerned with prognostication.

New York World’s Fair Button from the General Motors Futurama Exhibit. Image: www.tedhake.com

But, beyond the products of imagination (literature, art, and film), where can one actually go to get a tangible touch, a taste of the future? Not a virtual reality version, but rather an experience where one can actually wander around samples of a futurific world? The answer is—or rather, was—world’s fairs.

WORLD’S FAIRS — THE GEOGRAPHY OF WONDER

Humans also have a taste for novelty, adventure, the exotic, and news from beyond our borders (and products, material and cultural.) One phenomenon brings such appetites together with our fascination with the future: World’s Fairs.

World’s fairs were international events, taking place in intervals varying from several years to several decades. A city—like Paris, London, Osaka, New York, Seville, Rome - would be selected, and countries, states, companies, and trade organizations (and even religions) would erect pavilions - each of which would show the sponsor’s self-image and aspirations to the fair’s visitors (coming, often from all-over-the-world, during the fair’s few months duration.)

For countries, their industrial, consumer, and agricultural products would be featured, along with something of the nation’s culture—and generally there would be a lauding of the leaders, government, and “way of life”.

Companies, too, would extol their accomplishments, productive might, and the quality of their products. Most interestingly, they would often present displays about the forefront - The Future - of technology in their field. Sometimes such demonstrations were startlingly dramatic, but sometimes amusingly humanizing—like the talking (and joking) robot, Elektro (with his robot dog, Sparko), who were featured in the Westinghouse pavilion of the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair.

The architecture of the pavilions in world’s fairs have been particularly powerful evokers of “tomorrow.” Examples range from the jaw-droppingly giant (for that time) open space (377 feet x 1378 feet, and open to a height of 13 storeys) of the Galerie des machines in the 1889 Paris fair to the gargantuan geodesic dome of the US pavilion in Montreal’s Expo 67. Each building competed for the visitor’s attention—and, through striking shapes, unusual construction systems, and the manipulation of light (natural and artificial), often created dream-like, fantasy, forward-looking/futuristic icons. Sometimes a whole landscape would be populated by these odd, wonderful, future-dreamy buildings—like this view from Expo 67:

Photo: Laurent Bélanger from wikipedia

One of the most famous pavilions of the 1939-1940 New Fair was the “Futurama” exhibit created by Norman Bel Geddes for General Motors: using architecture, and giant, detailed, moving, and carefully lit models, it showed kinetic, luminous visions of tomorrow, beguiling visitors with an image of a motorized utopia. Upon leaving, attendees were given a button that read “I Have Seen The Future”—and no they doubt felt they had.

Even at the distance of decades, the images created by Bel Geddes and his team—and the future-oriented displays and architecture of the fair’s other pavilions—continue to fascinate, and evoke that “If only…” feeling. The great author William Gibson wrote of the ongoing seductiveness of such visions in his short story, “The Gernsback Continuum.”

NEW YORK AND THE FUTURE—AGAIN!

The New York World’s Fair, spoken of above - considered to be one of the greatest fairs of all - took place in 1939 and 1940, just before World War Two. But well after that war - in the midst of the 60’s, one of the USA’s most economically & militarily strong (and socially vibrant) periods - a second world’s fair was held in New York City.

Photo: Anthony Conti; scanned and published by PLCjr

That fair—the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair—was planned on the same pattern as the previous one: countries, companies, and groups each showing themselves off—only this time, with updated images of the future. For better-or-worse, the world had moved from planes to jets, from vacuum tubes to transistors, and from hydro to atomic power. The Future had new horizons—and that future was: Outer Space.

EVERY FAIR NEEDS A SYMBOL

Almost all world’s fairs have had a central building or structure—that serves to symbolize the fair. It is used both to distill the message of the fair, as well as to create an icon around which communication and marketing can be done (as well as being suitable for souvenirs!)

For the 1939 New York World’s Fair, that symbol had been the Trylon and Perisphere: these were huge platonic forms - a gigantic sphere and a spiky, towering, elongated tetrahedron (designed by Harrison and Fouilhoux). They were large enough for visitors to enter, and there was an exhibit inside about the city of the future (designed by Henry Dreyfuss).

Trylon & Perisphere Monuments of 1939 World's Fair in Flushing Meadows Linen Postcard. Photo: Michael Perlman

But for New York’s 1964-1965 fair, a new symbol would be needed. Here’s what Robert Moses - the fair’s boss - said about the search for a symbolic structure:

“We looked high and low for a challenging symbol for the New York World's Fair of 1964 and 1965. It had to be of the space age; it had to reflect the interdependence of man on the planet Earth, and it had to emphasize man's achievements and aspirations. … and built to remain as a permanent feature of the park, reminding succeeding generations of a pageant of surpassing interest and significance.”

A LOFTY VISION - IN CONCRETE

Concrete may be hard and heavy—but it can be manipulated make soaring structures of deft grace and even visual nimbleness. Nor does the concrete industry want to be thought of as stodgy, as they are always showing that they are moving ahead with forward-looking research and engineering—indeed, the American Concrete Institute once produced a set of research findings and projections on the possibility of using their material in a non-terrestrial environment, a book called “Lunar Concrete”!

The Portland Cement Association is, since 1916 “ the premier policy, research, education, and market intelligence organization serving America’s cement manufacturers. … PCA promotes safety, sustainability, and innovation in all aspects of construction, fosters continuous improvement in cement manufacturing and distribution, and generally promotes economic growth and sound infrastructure investment.”

Like other trade associations and companies, the Portland Cement Association wanted to be represented at the fair—and in a very forward-looking way. So they put forward a design for the fair’s central, symbolic structure—one that would embody a feeling of future-oriented optimism (and, of course, use portland cement!)—and they hired Paul Rudolph to design it.

THE GALAXON

Paul Rudolph came up with one of his most daring designs—and, given that Rudolph was one of the world’s most adventurous architects, that’s saying a lot.

His design was christened “The Galaxon”, and Architectural Record magazine reported:

“The Galaxon, a concrete ‘space park’ designed by Paul Rudolph, head of the Department of Architecture at Yale University, has been announced by the Portland Cement Association as ‘a proposed project’ for the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Its cost is estimated at $4 million.

Commissioned by the P.C.A. as ‘a dramatic and imaginative design in concrete,’ the Galaxon consists of a giant, saucer-shaped platform tilted at an 18-degree angle to the earth and held high above it by two curved walls rising from a circular lagoon. The gleaming 300-foot diameter disc of reinforced concrete would hover in the air like some huge space ship. Visitors would be lifted to the center of the ‘saucer’ by escalators and elevators inside the curved supporting walls. From the central ring they would walk outward over curved ramps to a constantly moving sidewalk on the disc’s outside perimeter. The sidewalk would rise and fall from the 160-foot high apex of the inclined disc, to a low point approximately 70-feet above the ground.

A stage is projected from one of its two supporting walls and a restaurant, planetary viewing station and other educational or recreational features could be located at points along its top surface to make it an entertainment center. The Galaxon was among several designs displayed at an exhibition in New York of the use of concrete in so-called ‘visionary’ architecture.”

- Architectural Record, July 1961

Rudolph did not disappoint—and he created drawings and a model to convey his striking design. The drawings themselves are impressive, with the main one stretching to nearly 20 feet long.

Photo of Rudolph’s presentation model. Image: http://www.nywf64.com

Drawing of night view (with spotlights). Image: "Remembering the Future," "Something for Everyone: Robert Moses and the Fair" by Marc H. Miller, published to accompany the 1989 Queens Museum exhibition "Remembering the Future: The New York World's Fair from 1939 to 1964."

A VISION SPURNED

The real power (to select the central, symbolic structure) rested with Moses - the famous (or, to some, infamous) Robert Moses, who’d built so many bridges, roads, and other facilities, all over the tri-state area. Of searching for an iconic central structure for the fair, he said:

“We were deluged with theme symbols - mostly abstract, aspirational, spiral, uplifting, flashing, or burning with a hard and gemlike flame, whose resemblance to anything living or dead was purely coincidental.”

Among the several many designs that Moses rejected was the Galaxon.

And so another structure was chosen, the Unisphere (made from a rather different material: stainless steel - and sponsored by a major manufacturer: US Steel). The Unisphere—still in place after all these years—admittedly has some uplifting visual power, and does still speak to the goal of a unified world.

But it’s not the forward-looking, FUTURE-evoking, space-expansive, upward-aspiring GALAXON.

Fortunately, we have Rudolph’s beautifully drawn visions to sustain our dreams.

PUBLICATIONS, ARCHIVE, AND EXHIBITION

When the Galaxon was originally proposed, it got some press—and it has since also appeared or been mentioned in books on Rudolph, and been on-exhibit.

Paul Rudolph was known for his virtuoso presentation drawings (especially perspectives and sections), and Paul Rudolph: Drawings is a beautiful, large book of them. It was edited by Yukio Futagawa, and published by A.D.A Edita Tokyo Co., Ltd. In 1972. The book includes a well-reproduced perspective view and a section of the Galaxon.

The preponderance of Paul Rudolph’s architectural drawings (well over 300,000 documents!) are in the Library of Congress. The collection includes several fascinating drawings of the Galaxon, which have been scanned and can be seen on-line.

Paul Rudolph’s original rendering. Image: Library of Congress

From the Library of Congress, impressively large, full-size reproductions of Paul Rudolph’s Galaxon drawing were made, which were very prominently displayed in the exhibit, Never Built New York (which was on-view at the Queens Museum from 2017-2018.) While the Galaxon didn’t make it into the exhibit’s catalog (the curators discovered it after the book had gone to press), the catalog is still well worth obtaining, as it is an exceptionally rich collection of visionary proposals for New York City - and it does include other fascinating projects designed by Paul Rudolph.

Paul Rudolph's Picasso

Photo: Seth Weine, Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation Archives

An Intriguing Object

Many visitors to the Modulightor Building are intrigued by the Picasso sculpture that’s on display within it—or rather, the several Picasso sculptures.

The origin of the artwork, and how they got here, is an interesting story…

A Very Public Artist

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) is widely considered to be the most famous artist of the 20th Century. He worked in a plenitude of mediums: painting, drawing, ceramics, printmaking, stage design, and sculpture.

But his art is not found only in museums and private collections—for his sculptural work includes several commissions of monumental scale, to be used in public settings. The “Chicago Picasso,” a 50 foot high sculpture in Chicago’s Daley Plaza, is probably the most well-known example:

New York City also proudly has one of Picasso’s large public works: the concrete “Bust of Sylvette”, situated in the plaza of “University Village” (a complex of three apartment towers designed by I. M. Pei):

NYC - Greenwich Village: Picasso's Bust of Sylvette. Photo: Wally Gobetz

A Commission for both Architecture and Art

In the late 1960’s-early 70’s the University of South Florida wanted to build a visitors & arts center for their Tampa-area campus. The building design was by Paul Rudolph, and Picasso was approached to provide a sculpture that would be the centerpiece of the center’s exterior plaza. It was to be over 100 feet high, and - had it been built - would have been the largest Picasso in the world.

Rendering of Paul Rudolph’s building with Picasso’s sculpture. Image: USF Special Collection Library.

An OK from Picasso

As a famous artist - indeed, a world-wide celebrity - one can imagine that Picasso was continually besieged about all kinds of projects. Carl Nesjar (a Norwegian sculptor—and also Picasso’s trusted collaborator, who fabricated his some of his large, public works) spoke to Picasso about the Florida project, and got an approval.

Nesjar said: “He liked the whole idea very much…. He liked the architectural part of it, and the layout, and so forth. That was not the only reason, but it was one of the reasons that he said yes. Because it happens, you come to him with a project, and he will say oui ou non … he reacts like a shotgun.” [Recently, a tape of Carl Nesjar speaking about the project has been found—a fascinating document of art history.]

Picasso’s Proposal

Picasso supplied a “maquette” of the sculpture—the term usually used for models of proposed sculptures. His title for this artwork was “Bust of a Woman.”

Picasso’s model. Photo: USF Special Collection Library.

The model was about 30” high, and made of wood with a white painted finish. Picasso gave the original to the University, and it is currently in the collection of the University of South Florida’s library.

“Bust of a Woman” sculpture with the audio reel of Carl Nesjar’s interview. Photo: Kamila Oles

The sculpture was to be towering—more than twice as high as his work in Chicago—and, at that time, would have been the biggest concrete sculpture in the world. Carl Nesjar made a photomontage of the intended sculpture, which gives an idea of its dramatic presence.

Carl Nesjar’s photomontage showing how “Bust of a Woman” would appear on the University of Southern Florida’s campus. Image: USF Special Collection Library

Not To Be

But, for a variety of reasons—cultural, political, and financial—the project never moved into construction: the university didn’t build the Picasso sculpture, nor Paul Rudolph’s building. That sad aspect of the story is covered in this fine article.

A Sculpture Greatly Admired by Rudolph

Although the project didn’t proceed, Paul Rudolph liked the sculpture so much that he requested (and received) official permission from Picasso to make copies of the maquette. Several faithful copies were made: the ones that are on view in the Modulightor Building.

Photo: Kelvin Dickinson, Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation Archives

A Virtual Life?

But this might not be quite the end for that Picasso sculpture, nor for Rudolph’s building design for that campus: they now have an existence - at least in the virtual world.

Kamila Oles (an art historian) & Lukasz Banaszek (a landscape archaeologist), working with the USF’s Center for Virtualization and Applied Spatial Technologies (CVAST) have created virtual models of what the building and sculpture would have looked like. You can also see a video of their process here.

Exciting visions - but ones that dramatically show an architectural & artistic lost opportunity.

NOTE: Several authorized copies were made - one of which will always be on permanent display in the Rudolph-designed residential duplex within his Modulightor Building. But the other authorized copies are available for sale to benefit the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation. Please contact the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation for further information.

Rudolph's LOMEX project featured in new Renderings

View from a terrace in the high-rises. Image: Lasse Lyhne-Hansen

Paul Rudolph’s Lower Manhattan Expressway project (LOMEX) has been digitally recreated by Danish designer Lasse Lyhne-Hansen. As featured on design websites Archdaily and Designboom, the work was created to celebrate Paul Rudolph’s 100th birthday.

Rudolph’s proposal for the Lower Manhattan Expressway. Image: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Robert Moses originally conceived of the Lower Manhattan Expressway project in 1941 and given the authorization to proceed in 1960. After numerous protests, including notable figures such as Jane Jacobs, the project which was to be an elevated highway was replaced by a sunken highway with adjacent parks and housing.

Then, writes Phil Patton in the Architects Newspaper:

In 1967 the Ford Foundation, whose new head was McGeorge Bundy (formerly National Security Advisor during escalation in Vietnam), asked Rudolph—known for large-scale projects—to imagine a development that ameliorated the impact of the highway. He proposed topping the sunken freeway with a series of residential structures, parking, and plazas, with people-mover pods and elevators to subways. The shapes of the buildings echoed the Williamsburg and Manhattan bridges, and also recalled Hugh Ferriss’ ideas of bridge/buildings from 1929. Rudolph’s idea was organizing a new city core around modes of movement.

“This plan, unlike most, does not propose to tear down everything in sight; it suggests that we tear down as little as possible,” Rudolph said about the project at the time.