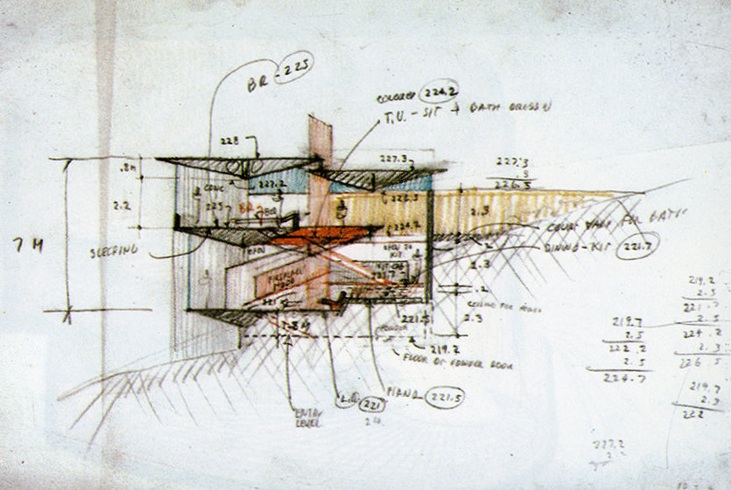

A night-time rendering of Paul Rudolph’s Channel 7 TV station headquarters building, designed for Amarillo, Texas.

The most well-known builders of pyramids were the Egyptians and several Mesoamerican civilizations—and even the Romans had one!

Pyramidal structures can be found in other parts of the world—from Indonesia to China to Greece (and now Las Vegas).

But Texas too?

Yes—via Paul Rudolph’s design for the headquarters of a TV station in Amarillo, Texas—a project of his from 1980. For a long time, the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation had very little information on this building: we knew it was commissioned by Stanley Marsh—one of Amarillo’s lively characters and a patron of the arts—and we had an address for the building, and Rudolph’s intriguing rendering (which shows it at night, with an array of lights blazing upwards from the center.) We still don’t know much about the commission—it will bear further research—but we do have some fresh images to share.

The building—its formal name and address being “1 Broadcast Center”—is still the home of KIIV, Channel 7—the ABC/CW+ station in Amarillo. KIIV has a long history in Amarillo, having first signed on-the-air in 1957.

The context for the building:

A satellite view of the neighborhood where the pyramidal TV station is located in Amarillo, Texas. North is towards the top, and the building’s roof is marked by the red arrow. Amarillo’s Elwood Park is at the far left, and railroad lines are at the right edge of the photo. The several forking roads, which merge towards at the bottom of the picture, converge to form US Highway 287. Image courtesy of Google: Imagery ©2019 Google, Imagery ©2019 Maxar Technologies.

A closer-in satellite view, looking down on the TV station’s pyramidal roof:

To get a sense of the building’s scale, one can compare it with the cars which are parked to the North, East, and South. At the bottom of the picture (at the South, just below the line of parked cars) is an array of the numerous types of antennas used by the station. Image courtesy of Google: Imagery ©2019 Google, Imagery ©2019 Maxar Technologies.

Ben Koush, AIA, is a registered architect, interior designer, and writer, based in Houston, Texas. He has a strong interest in history, and—fortunately for us—is also a photographer. You can see numerous examples of the images he’s captured on his Instagram page—and he’s given us permission to share the ones he’s taken of Rudolph’s TV station:

Front view of the Eastern side of the TV station building: KVII, ABC’s Channel 7 in Amarillo Texas, designed by Paul Rudolph. Photo © Ben Koush, used with permission.

A diagonal view. As in Rudolph’s rendering, the Channel 7 logo (and name of the staton) is prominent at the pyramid’s apex. Photo © Ben Koush, used with permission.

A view of the South side, with the station’s many antennae in the foreground. Photo © Ben Koush, used with permission.

A view from below the pyramid’s roof. The steel structures appears to support an open mesh sheathing, and the enclosed body of the building seems to be composed of a metal & glass curtain wall system. Photo © Ben Koush, used with permission.

Scott Fybush, based in Rochester NY, has also allowed us to show his photo of the building. Mr. Fybush has professional experience across all facets of broadcasting, and, under the Fybush Media banner, provides consulting services including signal expansion strategy, allocations, FCC filings and station brokerage. Here’s an image he shared with us—with Texas’ “big sky” clouds forming a dramatic background:

The station, as seen from the North. Image courtesy of Scott Fybush.

We are grateful to both Mr. Koush and Mr. Fybush for permission to use their photos—which allow us to convey some of the power of this Rudolph design.