A man of spirit and generosity, Ernst Wagner has been working to protect and educate the world about Paul Rudolph’s creative contributions.

Paul Rudolph the Artist? -or- When is a "Rudolph" not a Rudolph?

Definitely designed by Paul Rudolph: the General Daniel “Chappie” James Center for Aerospace Science and Health Education, at Tuskegee University—a architectural project from the early 1980’s—shown here being dedicated by President Reagan.

Although it has similarities to a number of Rudolph buildings (and the architect-of-record, Desmond & Lord, was a close associate of Rudolph on several projects), our assessment is that this college library is not a Paul Rudolph design.

IS IT A REALLY A RUDOLPH? - THE TASK OF ATTRIBUTION

From time-to-time, the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation is asked whether something is really a work of Paul Rudolph’s. That “something” might be from any facet of the great range of work to which Rudolph applied his creative energies: a building, a drawing, an object (i.e.: a light fixture), or—most intriguingly—an artwork.

In fact, we’ve recently been asked to comment on whether a painting is (or is not) by Rudolph. We’ll examine that possibility—but first: We’ll need to consider some of challenges of attribution, and also look at Paul Rudolph’s relationship to fine art.

There seems to be some cachet in having Rudolph’s name is attached to a house that’s for sale—and this even applies to houses that are not on-the-market, as some enthusiastic owners may want their home to be associated with the great architect. But not every such claim is true—and sometimes our assessment is that a building—to the best of our current knowledge—is not a Rudolph.

A CHALLENGING CASE

There are also cases where the relationship of Paul Rudolph to a project is not abundantly clear—and the matter needs investigation.

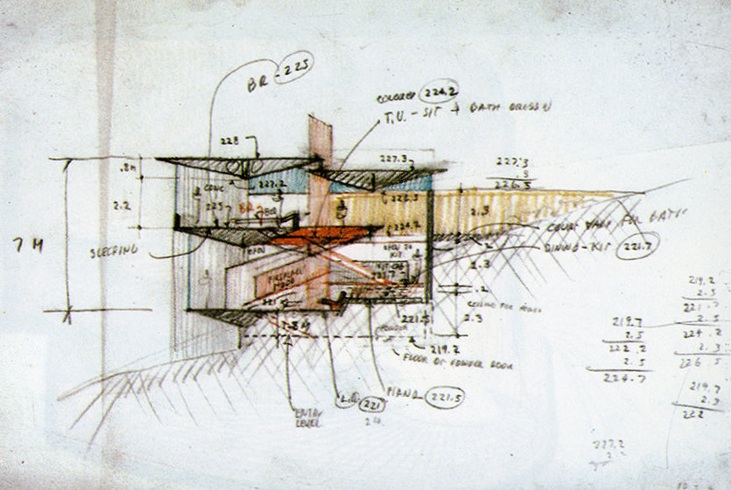

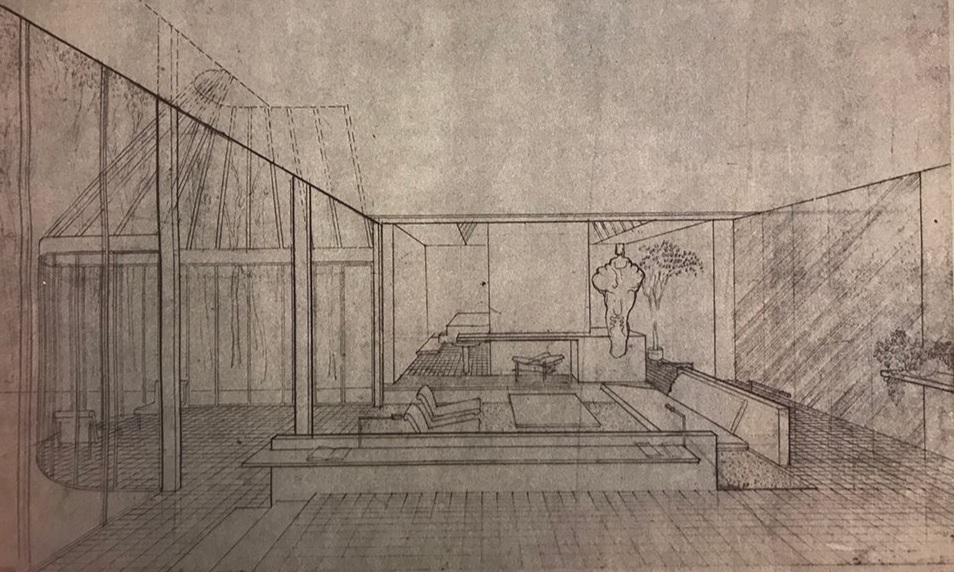

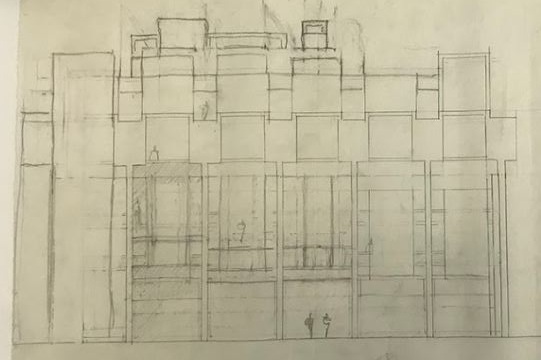

A drawing of a college library, done in Paul Rudolph’s perspective-section technique. Close inspection led us to assess that this is probably not actually a drawing by him—but rather: a drawing done in Rudolph’s spirit, possibly by someone that had worked closely with him.

For example: A staff member from a college library approached us. Their building was about to celebrate a half-century “birthday”—and they’d heard that it was designed by Paul Rudolph, and they asked us about it.

So was it? Well, it wasn’t on any of our lists of Paul Rudolph projects—but those lists were, over decades, edited and re-edited numerous times by Rudolph himself—and it’s possible that a project of his might have been left off those lists for any number of reasons. Another factor we considered was that the building’s architect-of-record had done other, important projects in close association with Rudolph. Moreover, the library building did exhibit some very Rudolph-like features. Also, the perspective-section drawing of the building was done in a manner resembling Rudolph’s graphic technique. But, after carefully looking at the building and the documents available to us, and also after consulting with some of Paul Rudolph’s past staff members, we concluded that the building was: “Rudolphian—but not a Rudolph.”

MULTIPLE RUDOLPHS?

There are other factors which, when working out an attribution, can lead one astray. One of them is when another person, with the same name, is also working in the same field and during the same era.

For example: For a long while, we were wondering about a rendering of a large, wholesale market facility for NYC: the Hunts Point Market. That’s a project which Rudolph had been asked to design—and we had documentation to prove that: the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation has an official press release from Mayor Lindsay’s office, explicitly announcing that Rudolph had received the commission.

The only image we’d ever seen of the proposed project looked nothing like a Rudolph design, nor was it done in his rendering style. Moreover, the rendering was done in tempera-gouache—a drawing medium which Paul Rudolph reputedly detested. Yet the drawing was signed “Rudolph”! Here was an architectural mystery.

ABOVE: A rendering found when researching Rudolph’s Hunts Point Market project. It is signed by “Rudolph”—but is nothing like a Paul Rudolph drawing. LEFT: A book celebrating winners of the Birch Burdette Long Memorial Prize for architectural rendering. The work of two different “Rudolphs”—the maker of the rendering above, and Paul Rudolph—are both in the book.

So was it? Only later did we come to understand that the Hunts Point Market rendering was by Rudolph, but a quite different one. The mysterious drawing was by George Cooper Rudolph (1912-1997)—an architect who was an almost exact contemporary of Paul Rudolph. George Cooper Rudolph’s main professional activity was as a renderer: he and his office were primarily engaged in making perspectives of proposed buildings for other architects and designers. He provided views for a large number of projects—and his prime medium was tempera-gouache, which was very popular at that time for such presentation drawings (although he did other things too.)

There’s another connection (beside the Hunts Point Market project) between the two Rudolphs. The Birch Burdette Long Memorial Prize was awarded annually for excellence in architectural rendering, and a book was published in 1966 showing drawings by 22 prominent winners. This work shown was by some of the best draftsmen/renderers of the 20th century. Here the two Rudolphs came together: included was a selection of work by George Cooper Rudolph—and on the book’s cover showed Paul Rudolph’s proposed design for the tower of the Boston Government Service Center [but, ironically, it was rendered someone else: Helmut Jacoby—yet another prize winner]

WHAT ABOUT FINE ART?

In the last few years, we’ve encountered several paintings which were attributed to Paul Rudolph. We believe these claims are made with total sincerity, and that the galleries offering these works have had some reason to assert that these are by the famous architect..

We’ll look at the three examples which we’ve come across—but before we do, we have to ask:

WAS RUDOLPH EVER KNOWN TO MAKE ART?

We come across little evidence that, as an adult, Paul Rudolph engaged in the making of fine art—and in the rare cases that he did so, it was only in connection with an architectural commission. It’s true that he appears, in his youth, to have loved to make art—and the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation has a vintage newspaper clipping showing a young Rudolph with a figurative sculpture that he’d made (for which he had won an award.) A memoir by his mother (also in our archives, and which you can read here) further testifies that he loved to make art when young. Doubtless, his higher education—including at architecture school—included one-or-more fine arts courses.

PAUL RUDOLPH BROUGHT ART INTO HIS BUILDINGS

An interior, circa 1963, within the recently completed Yale Art & Architecture Building—showing a large wall mural which Rudolph included in the building.

You can find Rudolph, several times, inserting art into his architectural renderings, showing where artworks might be located as part of a project’s overall design.

Not all such proposals were fulfilled, but some of his buildings did have art prominently incorporated into the architecture—like the two large murals by Constantino Nivola in his Boston Government Service Center. Artworks were also part of his interior design for his Yale Art & Architecture Building (wherein contemporary and ancient art were placed throughout the building) and in Endo Laboratories. Moreover, to the extent he could afford to do so, Rudolph included artwork in his own residences.

One further bit of data we’ve come across: there’s an interview with Rudolph—well into his career—during which he’s asked if he’d like to do fine art. He answers: Yes, he might like to do so—but doesn’t have the time.

RUDOLPH’S FIGURATIVE ART

The only times (post-youth) that we’ve found Rudolph making fine art are in two professional projects: one at the very start of his career, and the other during the decade of his greatest creative output:

ABOVE: Paul Rudolph’s Atkinson Residence, in which Rudolph’s mural was above the fireplace. BELOW: A longitudinal-section construction drawing of his Hirsch Townhouse. That house’s mural, also by Rudolph, was located in the large, open atrium space, shown in the left half of the drawing.

Rudolph’s very first professional project was the Atkinson Residence of 1940, built in Auburn, Alabama when he was 22 years old. The living room features a 6' high x 10' wide ornamental mural above the fireplace—most likely a consequence of Rudolph attending a required class on 'Mural Design' while in school. The mural’s linework is composed of V-shaped grooves, cut directly into the plaster.

The next time (and the last time that we know of) when we see Rudolph-as-artist is at least a quarter-century later: in his 1966 design for the Hirsch Townhouse in Manhattan (the residence that was later to become famous as the home of fashion designer Halston.) Rudolph covered a prominent wall in the living room with a large mural—about four times the area of the one done in Alabama—but also done in with the same technique: making lines by the cutting of grooves.

What the two artworks share in-common are:

both artworks are figurative,

viewers can readily discern several people and objects

they both have a dream-like (or story-book) quality

both have highly stylized imagery

The mural from Rudolph’s 1940 Atkinson Residence, in Auburn, AL, located above the Living Room’s fireplace.

The mural from Rudolph’s 1966 Hirsch Townhouse. Its scale can be judged by seeing the client standing in-front.

HIS PROFESSIONAL ARTISTRY

Paul Rudolph did engage in 2-dimensional artwork—but of an applied, professional nature.

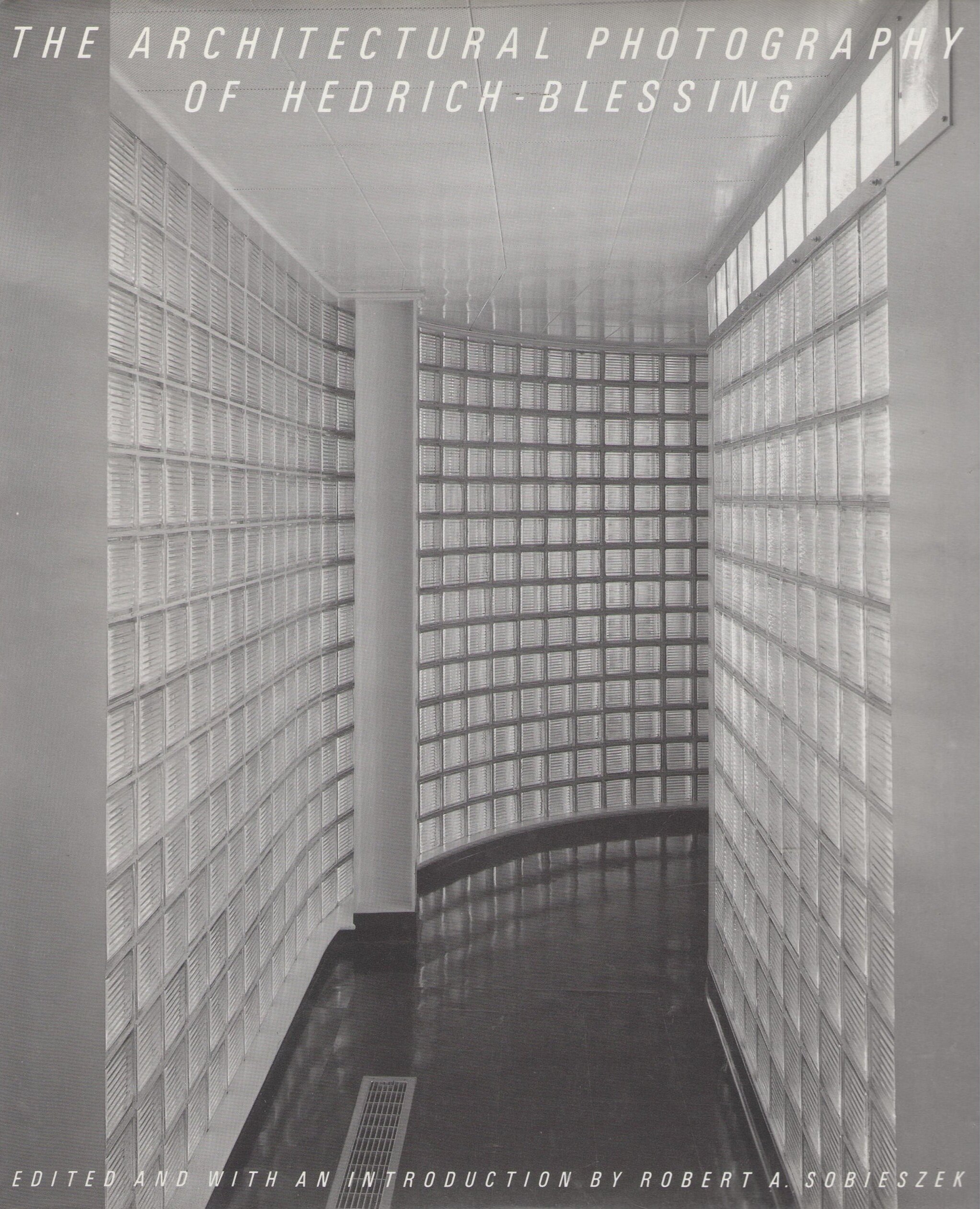

We’re referring to his famous perspective renderings (especially section-perspectives). An entire book was devoted to these drawings (see cover at right)—with his section-perspective drawing of the Burroughs Wellcome building being given the front cover.

In Paul Rudolph’s renderings after he left Florida, he generally eschewed the use of continuous tone (a position consistent with his dislike for gouache renderings.) His fine control of linework (often linear, but sometimes flowing) was what Rudolph utilized when he needed to generate tonality—and he achieved that through hatching and line density, to arrive at the effects he desired.

Interestingly, Rudolph’s line-oriented techniques, which he used for his architectural renderings, are not-so-different from the techniques utilized in his two murals.

PAUL RUDOLPH AND TOPOLOGY-AS-ART

The relationship of a topo map’s curved lines (bottom) with the layers of a 3D model version (top.)

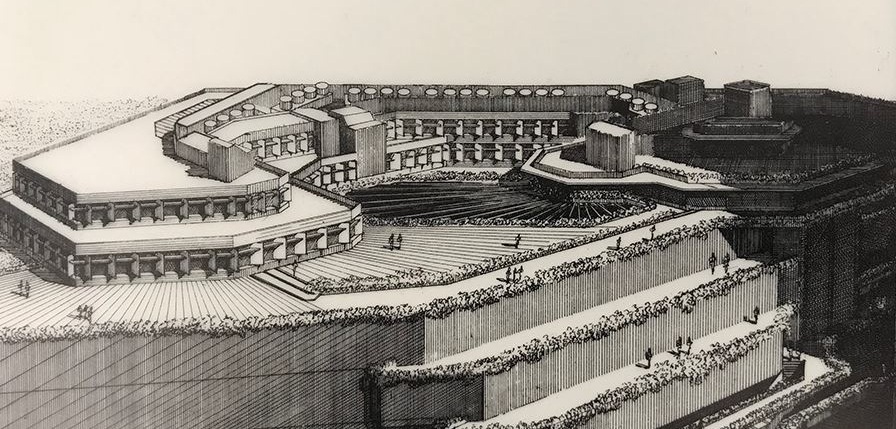

A portion of the Stafford Harbor model. The model’s topo layers, reflecting the hilly nature of the inland part of the development’s site, are most evident in the upper-right area of this photograph.

Before a more direct consideration of Paul Rudolph’s engagement with fine art, it’s worth noting the formal affinity between the sinuous sets of closely-spaced lines (that one finds in Rudolph’s two murals,) and the lines produced when making topo maps and topo models. Using a topo system, in drawings and models, was a standard practice in architectural offices—including Rudolph’s.

Most sites are not flat—so architects study such sites with “topo maps.” These maps have numerous lines, whose closeness-or-distance to each other graphically convey an area’s steepness-or-flatness. When this gets translated into 3-dimensions—to create a “topo model”—the model is made of a series of layers (of boards), the edges of which follow the curves of the map.

Rudolph’s office produced numerous models of his proposed designs—and when a site was hilly, the buildings were set upon such “topo model” bases. The flowing lines of these models (the result of showing the contours of the land in this way) was visually pleasing to Rudolph—so much so, that Rudolph “decorated” his work spaces with those models.

A prominent example of the use of the topo technique is his large model for Stafford Harbor, a project of the mid-1960’s. The Virginia project comprised a master plan, and the design for townhouses, apartment houses, a hotel, boatel, as well as commercial spaces. It embraced the site’s topography—and one can see in the model which Rudolph’s office produced for the project that each layer conveys a change in height.

The full model was gigantic—and Rudolph suspended it, vertically, in the entrance to his architectural office. He used the model’s aesthetic appeal (and surprising orientation) to create a wall-sized, art-like “hanging” that brought additional drama to his office’s multi-storey space.

Moreover, when Rudolph was Chair of the School of Architecture at Yale (in the Yale Art & Architecture Building that he designed, now rededicated as Rudolph Hall), he situated a topo-like mural by Sewell Sillman in the atrium of the main drafting space—both as inspiration and for its aesthetic appeal.

A topo-like mural by Sewell Sillman, placed above the main drafting room/atrium, in Paul Rudolph’s Yale Art & Architecture Building (now rededicated as Rudolph Hall.)

Rudolph “decorated” his work spaces with topo models—like this one of Stafford Harbor—placed dramatically at the entry of his Manhattan architectural office.

PAINTINGS BY RUDOLPH?

We’ve come across several works that have been attributed to Rudolph. Each have an aesthetic appeal—but are they really by Paul Rudolph-the-architect?

EXAMPLE ONE:

The painting at right has been claimed to be by Rudolph. The back is has two labels giving the attribution, and the front has a signature.

While we cannot discount all possibilities, we’d say this painting’s compositional strategy is one characterized by the fracturing of the image—an aesthetic that Paul Rudolph does not usually follow. Rocco Leonardis (an architect and artist who had worked for Rudolph) says “Architects make Wholes”—and that well characterizes Rudolph’s work. In contradistinction, this painting’s collage-like conception is closer to the approach taken by Robert Delaunay in his famous depiction the Eiffel Tower (see below-left): a breaking-up of the object.

Paul Rudolph, in his perspective renderings, was noted for his linework—and the painting certainly relies on a multitude of lines to convey the subject. But whereas one senses that Rudolph’s lines are well-controlled—in the service of creating precise images of a projected architectural design—the lines in the painting are explosively staccato.

The painting’s “line quality” has more of an affinity with the work of Bernard Buffet, whose drawing-like paintings (and even his signature) are filled with a shrapnel-like energy (see below-center).

Combining the painting’s fragmented forms and line quality, we can see them used simultaneously in a canonical work of 20th century Modernism: Lyonel Feininger’s 1919 cover design for the manifesto of the Bauhaus (see below-right.)

Of course we’re not suggesting that any of those artists had a hand in the making of the painting (except, possibly, as inspirations)—but only point out that their artwork is closer to the painting than any of Paul Rudolph’s work.

A painting by Robert Delaunay

A painting by Bernard Buffet

A print by Lyonel Feninger.

Signatures on an artwork count for a great deal, and here we can see a close-up of the one on the painting:

Paul Rudolph’s actual signature.

In the course of our work at the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, we’ve seen Paul Rudolph’s signature hundreds of times—and at right is a representative example.

As with any signature, one can find a bit of variation in Rudolph’s signatures—but our observation is that his signature is fairly consistent over his lifetime—and it does not seem to resemble the one in the painting. There’s also a label attached to the back, with a note on it, and it appears to be in another language (German). The name “Paul Rudolph” appears within the handwritten note—but it too does not match Rudolph’s signature.

Based on the discrepancies between the painting and Paul Rudolph’s work and signature, we do not believe the painting is by Paul Rudolph (at least not our Paul Rudolph)—but we are open to a reassessment if additional information is discovered.

EXAMPLES TWO AND THREE:

If you do a Google search for “ ‘Paul Rudolph’ painting ” only a couple of other artworks show up—and below is a screen grab of the results:

A screen capture of a portion of a page from Google Images, showing results when the search request is set for “ ‘Paul Rudolph’ painting”

Both are attractive works, and each is done in oil (the left is oil-on-canvas, and the right is oil-on-paper)—and both were attributed to Paul Rudolph. They were offered or sold through galleries/auction houses who are distinguished for the quality of the artworks they offer and the depth of their knowledge. So, as with the painting in Example One, we conclude that such attributions were made in good faith, and to the best of the seller’s knowledge.

So might these be by Paul Rudolph?

We have a date for the right-hand one: 1958. The 1950’s was the era in Rudolph’s work when he began to move from Bauhaus orthogonal rectilinearly (as exemplified by the Walker Guest House, 1951-1952) towards a more muscular (and even sculptural) manifestation of that aesthetic (the most powerful example is his Yale Art & Architecture Building, 1958) and he was also beginning to incorporate dramatic curvilinear forms (as in his Garage Manager’s Office project, 1961). These Rudolph works don’t have a formal vocabulary which resonates with those paintings.

FINE ART OF THAT ERA: THE DOMINANT MODE

ABOVE: Harry Bertoia’s altar screen within the MIT Chapel; BELOW: Jackson Pollock’s painting.

But, no matter how much Rudolph explored architectural forms, it must be acknowledged that he was still a child of the Modernist era—and that included being educated by the founding director of the Bauhaus itself—Walter Gropius.

When the paintings attributed to Rudolph were being made, abstraction and abstract expressionism were the popular style among painters and sculptors.

Two artists who manifested the sprit of that period were the sculptor Harry Bertoia (1915-1978) and the painter Jackson Pollock (1912-1956)—both born within about a half-decade of Paul Rudolph, and coming to prominence about the same time.

Consider two works by those artists: Bertoia’s altarpiece screen (reredos) for the MIT Chapel (the building was completed in 1956, and its architect was Eero Saarinen), and a 16 foot wide painting by Pollock from 1952.

Those two works share several characteristics—ones seen with some frequency in the artwork of the era:

energy/movement

fragmentation

linearity—but often without alignment

a discernable design—but one that embraces a mixture of chaos and order

generally they are non-non-figurative—or, if the figure (a building or body) is included, the imagery is pushed towards abstraction

a restricted palette (or limited range of tones/finishes/materials)

All of these are also shared by the paintings attributed to Paul Rudolph. You could say that those two works are consistent with the fine-arts style of the era in which they were created. In other words: they truly “make sense” for their time. But they don’t match Paul Rudolph’s form-vocabulary of that era.

THE QUESTION REMAINS: ARE THEY RUDOLPHS?

We can’t rule out that Paul Rudolph, some time mid-century, may have briefly tried his hand at painting. But, given all we know—

his practice was feverishly busy at the time

his work, at this time, does not have any formal resemblances to the artworks

linework—a significant part of all the artworks—is unlike the the type of linework which Rudolph used extensively in his work

he was simultaneously leading a major educational institution (as Chair of Yale’s School of Architecture from 1958 -to-1963), as well as engaged in the titanic work of designing its famous school building

his two known artworks (the murals) are figurative, and of an utterly different character

the signature we’ve seen (on the first painting shown above) doesn’t match the many signatures on Rudolph documents in our archive

no other Rudolph artworks of a similar style have come to light

So the “balance of probabilities” leads us to conclude that those paintings may be by a Paul Rudolph, but not likely by the architect Paul Rudolph.

BUT PAUL RUDOLPH DOES INSPIRES ARTISTS…

Rudolph himself might never have made two-dimensional artworks on paper or canvas—but he may have inspired the artwork of others, and below are two examples where that seems to be the case.

EMILY ARNOUX

Emily Arnoux is an artist from Normandy, and she has exhibited with the Fremin Gallery in New York City. Her recent show there featured vividly colored images of pool-side scenes, and her gallery says of her:

“From a young age, she became fascinated by the ocean and the laid back lifestyle surf-culture engenders. Her work captures the divine energy and the jubilation experienced when diving into cool water. . . . Arnoux’s [work feels]. . . .at once contemporary and modern, recalling beach-side postcards of the 1950s & 60s.”

What intrigued us is some of the architecture which is included in her works, and one of her wonderful paintings in particular—“Cubes Game”—seems quite resonant with Paul Rudolph’s Milam Residence of 1959, in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida. Above is a mosaic of images from Ms. Arnoux’s paintings—and, below, you can see her “Cubes Game” side-by-side with Rudolph’s Milam Residence.

Paul Rudolph’s celebrated Milam Residence in Florida

Emily Arnoux’s superb painting, “Cubes Game”

Emily Arnoux’s paintings are full of life and color—and if Rudolph’s work was of any inspiration to her, we are delighted.

SARAH MORRIS

Sarah Morris is a New York based artist whose works are in major museums throughout the world. Her paintings embrace color and geometry. Occasionally they utilize forms from typography, but most often they are abstract, relying on composed linear and circular elements and areas of color.

Morris’ 2018 exhibit at the Berggruen Gallery in San Francisco showed then-recent drawings and paintings (as well as a film by her.) Her gallery said of Morris (and of that exhibit) that she is:

“. . . .widely recognized for her large-scale, graphic paintings and drawings that respond to the social, political, and economic force of the urban landscape through a visual language grounded in bold and ambitious abstraction. Her probing of the contemporary city inspires a consideration of the architectural and artistic climate of modernity and humanity’s footprint—a subject that Morris energizes and invigorates through a distinct use of geometry, scale, and color. . . .Asymmetrical grids form futuristic compositions of sharply delineated shapes separated by rigid borders and acute transitions between colors. The grid-like quality of her work evokes city plans, architectural structures (including a staircase designed by Paul Rudolph), tectonic plates, or industrial machinery. . . .”

That text referred to a work by Sarah Morris titled “Paul Rudolph”. The painting’s medium is household gloss paint-on-canvas, and it is 84-1/4” square, and was created in 2017. In this work, too, we see Rudolph inspiring an artist’s creativity.

Sarah Morris’ fascinating painting from 2017, “Paul Rudolph”

RUDOLPH AND ART

Paul Rudolph engaged with art in various ways—his medium is architecture—but, to the best of our knowledge, we believe that the paintings that have been attributed to him are not by Paul Rudolph-the-architect.

But we are happy to see Paul Rudolph inspire others working in the fine arts!

IMAGE CREDITS

NOTES:

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation (a non-profit 501(c)3 organization) gratefully thanks all the individuals and organizations whose images are used in this non-profit scholarly and educational project.

The credits are shown when known to us, and are to the best of our knowledge, but the origin and connected rights of many images (especially vintage photos and other vintage materials) are often difficult determine. In all cases the materials are used in-good faith, and in fair use, in our non-profit scholarly and educational efforts. If any use, credits, or rights need to be amended or changed, please let us know.

When Wikimedia Commons links are provided, they are linked to the information page for that particular image. Information about the rights to use each of those images, as well as technical information on the images, can be found on those individual pages.

CREDITS, FROM TOP-TO-BOTTOM, AND LEFT-TO-RIGHT:

Tuskegee dedication by President Reagan: source unknown; Library building, for which Desmond & Lord was the architect: photo by Daderot, via Wikimedia Commons; Section-perspective drawing: screen grab from Framingham State University web page; Architectural Renderings book: a copy is in the collection of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation; Rendering of Hunts Point Market: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; Interior with mural of the Yale Art & Architecture Building: photo by Julius Shulman, © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles; Atkinson Residence: photograph by Andrew Berman, from the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation; Hirsch Townhouse longitudinal construction section drawing: © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation; Atkinson Residence mural: © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation; Hirsch Townhouse mural: © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation; Paul Rudolph drawing book: a copy is in the collection of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation; Topo map diagram: Romary, via Wikimedia Commons; Stafford Harbor model: photographer unknown; Main drafting room of the Yale Art & Architecture Building, 1963: photo by Julius Shulman, © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles; Paul Rudolph’s architectural office’s entry area: © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation; Tall painting attributed to Rudolph: supplied to us by owner; Robert Delaunay painting: via Wikimedia Commons; Bernard Buffet painting: AguttesNeuilly, via Wikimedia Commons; Lyonel Feninger print: Cathedral (Kathedrale) for Program of the State Bauhaus in Weimar (Programm des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar)1919; Close-up of painting with signature: supplied to us by owner; Paul Rudolph signature: from the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation; Paintings attributed to Paul Rudolph: screen grabs from Google Images; Walker Guest House: photo by Michael Berio. © 2015 Real Tours. Used with permission; Yale Art & Architecture Building: photo by Julius Shulman, © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles; Garage Manager’s Office: © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation; Bertoia altar screen within MIT chapel: Daderot, via Wikimedia Commons; Pollock painting: via Wikimedia Commons; Mosaic of Emily Arnoux paintings: screen grab from Fremin Gallery web page devoted to the artist; Milam Residence: Joseph W. Molitor architectural photographs collection. Located in Columbia University, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Department of Drawings & Archives; Arnoux painting, “Cubes Game”: from Emily Arnoux web page; Sarah Morris painting, “Paul Rudolph”, screen grab from Berggruen Gallery web page devoted to Sarah Morris’ 2018 exhibition.

How Architects See (LITERALLY)

HOW TO SEE (AND WHO’S NOT SEEING)

Though one of America’s most famed and sought-after designers, George Nelson (a contemporary of Paul Rudolph), who worked on industrial design and architecture commissions for well-known clients—was frustrated. He found that his clients—the leaders of major institutions and corporations—just couldn’t see.

The statue of Minerva presides over the drafting room in Paul Rudolph’s Yale Art & Architecture Building. Photo by Julius Shulman.© J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

Yes, they could see well enough to drive a car or hit a golf ball, but the visual distinctions which architects and designers make—the vibrancy with which they apprehend the world, which in-turn allows them to create objects and environments of vivid creativeness—were lost on almost everyone outside of the design community (including many of Nelson’s clients).

Visual awareness of the world (beyond the most basic needed to function) was virtually non-existent for most of the people for whom Nelson was working. Taking-on this challenge like a design-problem, he developed various tools: presentations, reports, and eventually a book—"How To See”—to try to introduce non-designers to a the way architects, designers, and artists see the world around them.

[There’s an interesting convergence between Rudolph and Nelson: the figure on the cover of Nelson’s book, How To See, bears a striking resemblance to the statue of Minerva, the goddess of wisdom—the sculpture which Paul Rudolph chose as the focus for the main interior of his Yale Art & Architecture Building.]

CONSEQUENCES

There are serious consequences to this mass un-seeing: decision-makers who own or determine the future of Rudolph-designed buildings—who may have little ability to see and discern those buildings’ true value—have sometimes opted for changes that are not sympathetic with Rudolph’s architecture, or they’ve even decided for wholesale demolition.

Those who seek to preserve great architecture—one of the central missions of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation—go up against this “unseeing” every day. So there is a continuous need for a “How to See” campaign, to open the vision of non-designers to the splendors and value of the visual-architectural world.

Wright was undeniably a man of great style, controlling his image though an ongoing program of self-generated publicity. He’s hardly ever shown in photographs wearing glasses—yet toward the end of his life he was captured with them, as shown in this article from a late 1950’s issue of Architectural Record. Courtesy of: US Modernist Library.

BUT WHAT HELPS ARCHITECTS TO SEE?

One could argue that architects have no problem with appreciating the visible world. Indeed, they embrace it with the perceptual equivalent of a craving appetite. But what happens when their own ability to see—their acuity of vision—begins to literally falter?

What happens is: Glasses—and, if you can count on anything, it’s this: architects (and their colleagues: designers and artists) will not be content with just any pair of glasses. What they seek is a personal style which fully expresses their overall design vision, including their self-image—and that extends to their choice of glasses.

And what’s more expressive of the Modern spirit than that purist, platonic, and machine-like design: the Circle.

[Note: We’ve had an article on Rudolph’s focus of the circle in his design work—Paul Rudolph and Circular Delight—which you can read HERE.]

THE LE CORBUSIER LINEAGE

The origin-point of the “lineage” of architects adopting the perfect circle for their eyeglasses seems to start with Le Corbusier. Like Wright, he was strategic about his self-presentation—from the layout of his many publications -to- the details of his attire. As the exponent of mechanization in the conception of buildings (“The house is a machine for living.”), and geometric Purism in art, it’s natural that he’d choose circular eyeglasses—and they became his personal signature.

Le Corbusier, wearing the circular eyeglasses which became his his personal signature. Left, his glasses have relatively thin frames outlining the lenses. Above, he’s shown with the thicker frames with which he is more frequently associated. Photos courtesy of Wikipedia

THEN JOHNSON…

The next step in the lineage seems to be Philip Johnson. In Mark Lamster’s fascinating biography of Johnson—The Man in the Glass House: Philip Johnson, Architect of the Modern Century—he speaks of Johnson’s adopting the Corbusian eyewear by the mid-1960’s:

“. . . .Philip Johnson was happily stepping into the role of ‘Philip Johnson,’ a public persona that he cultivated and refined, now augmented by the owlish glasses that he had begun to wear, another borrowed statement, this time from Le Corbusier. . . .”

Architect Philip Johnson (1906-2005), photographed late in his life—and still wearing the Corbusian circular glasses that he had adopted as part of his image, much earlier in his career. Photograph by B. Pietro Filardo, courtesy of Wikipedia.

A scan of the New York Review of Books web-page with the opening of Martin Filler’s review of Lamster’s biography of Philip Johnson. On that page was David Levine’s caricature of Johnson—featuring his Corbusian glasses—and a forehead evocative of the broken pediment of Johnson’s AT&T Building.

I. M. Pei—the famous architect also chose the circular glasses style. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

AND THEN PEI…

The next prominent architect who was widely noted for wearing the circular style of eyeglasses was I. M. Pei. Photographs of Pei, throughout his long and prolific career, show him wearing them, generally with black (or dark) frames. But in this late photograph, from 2006, he’s shown with medium-thickness, tortoise-shell frames (instead of the more Corbusian black ones.)

AND RUDOLPH-IAN ROUNDNESS…

At this point, we have to bring in Paul Rudolph, He wore a number of different styles of glasses (mainly with strong-looking black frames)—but seems to have settled on the circular Corbusier style as his glasses-of-choice.

Indeed, Paul Rudolph appears to have become attached to using that style alone— We’ve heard an anecdote about this from a fellow who had a friend who worked for Rudolph: he encountered his friend on the street, carrying an armful of those circular glass frames. The friend explained: Paul Rudolph had heard that those round frames might go out of production—so Rudolph sent his employee to the glasses shop to buy-out the entire stock of that design!

The collections of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation includes several pairs of Rudolph’s eyeglasses—including the an example of the circular style (the right-most one in the above photograph). © The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation Archives

CIRCULAR CIRCULATION…

After the initiation of this lineage, and its first generations of adherents— Le Corbusier > Johnson > Pei > Rudolph—it’s not hard to find these geometric glasses spreading among architects. Nicholas Grimshaw is among the more famous wearers of the style—and, if one re-defines the net to a wider circle of the creative class, we’d be amiss to not mention the circular glasses which have become a trademark of artist David Hockney.

Before leaving the topic, we want to note three more truly historic figures—who, like Paul Rudolph, have altered the course of architecture—all of whom are adherents of the circular style in eyewear: Peter Cook, Denise Scott Brown, and Peter Eisenman.

Peter Cook. Photo by CRAB, courtesy of Wikipedia.

Peter Eisenman. Photo by Columbia GSAPP, courtesy of Wikipedia.

Denise Scott Brown. Photo by Columbia GSAPP, courtesy of Wikipedia.

P.S. WAS LE CORBUSIER REALLY THE FIRST?

Who really first initiated the circular eyeglasses style, among architects, might be—ultimately—an unsettleable question.

We do have these intriguing photos of the architect Julia Morgan (1872-1957), and her contemporary Hans Poelzig (1869-1936). Both of their lives overlapped Le Corbusier’s—but more relevant is that both their careers started well before Corbusier’s—and one might reasonably propose that Morgan’s and Poelzig’s sense of personal style (including eyewear?) coalesced before Corb’s.

Julia Morgan (1872-1957.). A skilled architect who worked on a variety of building types, is best remembered for her her design of the Hearst Castle complex. It’s hard to tell, in this vintage photo, if her glasses were perfectly circular—but if not, they were certainly close to that geometry. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.

The architect Hans Poelzig (1869-1936). In both images—him at work (above), or in a more formal portrait (at right)—he is pictured wearing eyeglasses which embrace the purist circular geometry. Here he is photographed circa 1927 by Alexander Binder Both photos of Poelzig (above and right) are courtesy of Wikipedia.

Poelzig’s design work could be dreamlike and fanciful, or severely functionalist—but he always showed an appreciation of the power of geometry. That concern extends even to his his personal appearance. Photograph by M.E.

Moreover, circular forms for eyeglasses go back to the beginnings of corrective eyewear—-the circular form of lenses being easier to shape (grind). Finally, one should always recall the eternal power and fascination of that perfect form, the circle—something that has has eternally fascinated philosophers and designers!

ROLLING FORWARD WITH THE THE CIRCULAR STYLE…

If you want to join with Le Corbusier, Paul Rudolph, and Denise Scott Brown in wearing the circular style, then fear not: there are abundant examples on the the market. In fact, just putting “architect’s circular eyeglasses” into an internet search box will yield results like this, or this below—

CIRCULAR CINEMA

And, if you want to revel in the way that the circular eyeglasses mode has been integrated—with humorous thoroughness—into the conventions of architectural attire, you’ll enjoy “MISTER GLASSES”—a series of short films created by Mitch Magee.

Magee is a writer, director, producer, and actor—and he adroitly applied all those talents (in collaboration with a talented ensemble) in creating this series. Mitch Magee also plays the eponymous Mister Glasses—a character whose authentic concern for others is mixed (in a wonderfully strange way) with a lack of visible emotional affect.

Each of the brief-but-sharp episodes brings the main character and his team into a series of architecturally-related preachments. But the humor—and perhaps the point—of the series emerges not so much from the plots, but rather in the way that Magee shows (and caricatures) the ways that Modern architects think and respond to the world.

One of the joys of the series is the way that Mister Glasses is portrayed as the quintessential Modern architect—“Modern” in the particular sense of adamantly adhering to the classic palette of the International Style. But he also continually manifests that strand of Modernism in a highly personal way: he conveys, in his manner, speech, and self-presentation, a sense that he’s living in a Platonic world—or at least aspires to. Thus Mister Glasses’ speech verges on clipped, his suits are consummately tailored and maximally restrained in style (much like Mies van der Rohe’s), and—of course!—he wears platonically circular glasses.

AND IN RETROSPECT…

Eyeglasses (circular and otherwise) have been an everlasting motif in art—and this is delightfully studied in LENS ON AMERICN ART: The Depiction and Role of Eyeglasses. Richly illustrated, and beautifully published by Rizzoli/Electra, art historian John Wilmerding delves into the many occurrences, uses of, and varied possible meanings of eyeglasses, as they show up in American art. Enthusiasts of the circular mode in eyeglasses will be glad to know that a notable number of examples of their favorite style are shown in his delightful book.

John Wilmerding’s book, LENS ON AMERICAN ART: The Depiction and Role of Eyeglasses, includes numerous examples of the circular eyeglasses style in artworks made throughout American history. The author, shown above, has given an interview about the book, which was published by Rizzoli/Electra on the occasion of an exhibition at the Shelburne Museum. This insightful book can be ordered directly through the publisher.

Rudolph And His Architectural Photographers — PART TWO

P. J. McDonnell’s photograph of the Burroughs Wellcome building, in its current state, shows how great architecture has the power to always maintain its dignity. Photograph courtesy of © PJ McDonnell, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation Archives

In the first part of this study, Paul Rudolph And His Architectural Photographers—PART ONE, we looked at some of the most important architectural photographers of the 20th Century—Stoller, Kidder Smith, Molitor…—ones whose work had included a focus on the architecture and interiors of Paul Rudolph.

PART TWO—this article—will look at architecture & interiors photographers of the current era (almost all of whom are now very active!) whose work has also focused upon Rudolph. While this is not an exhaustive review of every photographer who has taken on that fascinating subject, it does show that an impressive range of talents have turned their attentions to Rudolph.

Above: Paul Rudolph’s bedroom, within his penthouse apartment. Below: an interior of the Modulightor Building. Photographs © Peter Aaron / OTTO, Archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

PETER AARON

Peter Aaron writes of his work: “I have been shooting architecture and interiors for thirty-five years. I started my career as a cinematographer, but consistently found myself more attracted to still photography. After working for designers Ward Bennett and Joseph d’Urso as they developed their High Tech style, I began a transformational apprenticeship with the great architectural photographer Ezra Stoller. After two years I began working on my own, adopting Ezra’s strong compositional approach while developing an individual style through the use of dramatic camera angles, theatrical lighting, and cinematic techniques. Since that time I have photographed structures by many of the most influential and groundbreaking architects of the last thirty years, including Robert A.M. Stern, Rem Koolhaas, Charles Gwathmey, Michael Graves, Peter Eisenman, Robert Venturi, Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, and Raphael Vinoly. I have been a contributing photographer for Architectural Digest and my images frequently appear in other magazines and books.” You can see an extensive selection of his work here, and learn about his recent book here.

AARON AND PAUL RUDOLPH: In 2018, the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation created two exhibits to celebrate Rudolph’s centenary, and also published corresponding catalogs for each. In preparation for these exhibits, while researching within our archives, we came across a beautiful image of Rudolph’s own bedroom within his Beekman Place Quadruplex penthouse—and that photograph was by Peter Aaron. We contacted Mr. Aaron and he graciously gave us permission to use the photograph. This opened up a dialogue with him, the result of which is that he has gone on to make light-filled photographs of the interiors of Paul Rudolph’s Modulightor Building (which you can see on that building’s project page.) Mr. Aaron has written of his goals: “As a photographer, my mission is to provide an image that’s a sort of ‘Platonic ideal’ of each structure, to show the building as the architect originally envisioned it…” —and we believe that his photographs of the work of Paul Rudolph are superb examples of the achievement of that aim.

One of the spectacular interiors of Paul Rudolph’s Deane Residence. Photograph © John Dessarzin

JOHN DESSARZIN

Mr. Dessarzin is a professional photographer of many decades experience, whose work has hardly been restricted to architectural subjects. As his impressive portfolio shows, his photography has focused on the human form, nature, news events, the famous and the anonymous, the foreign and the domestic—as well as architecture. Of that subject, he says: “At times [he pictures] the ineffable splendor in modern architecture as a haunting, commercial phantom among the iconic, storied skyscrapers of profit. In other instances, he presents ancient stone singularities as a charismatic existence that amply forges, but also devours human character in shades of ambivalence suggesting confused or decadent aspects of civilization.” Clearly, this is a photographer who is using his visual work to reach beyond the tangible to the ineffable—a commendable goal for any artist. You can learn more about him, and see his artistry in light and color, here.

DESSARZIN AND PAUL RUDOLPH: Paul Rudolph’s Deane Residence—a design he commenced at the end of the 1960’s—is known for its empathic use of structure, with geometrically composed framework expressed on both the exterior and interior. We came across a suite of photos of this dramatic design—images of spectacular color and drama—and it was the work of John Dessazin. He has graciously allowed us to include them on the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s project page for this house.

ED CHAPPELL

Ed Chappell, based in Florida, is a photographer with a special eye for the splendor of color in shooting architecture, fashion, landscape, and other subjects. He says of his work “I capture images. Make visions visible. Bring concepts to light. . . .I’m faced with challenges of every description—each of which calls for a unique solution, and all of which present the same demand: make it work. . . .You have to know the rules to break the rules, which may be exactly what is required. Experimentation and thinking ahead always pays off.” His website, here, displays a great range of his work.

CHAPPELL AND PAUL RUDOLPH: Paul Rudolph’s home in New York City, his “Quadruplex” penthouse, has been photographed a number of times. Perhaps the best article (with the most complete set of pictures) that has ever been published on it—as it looked the way that Rudolph had occupied and furnished it—was in a 2007 issue of Florida Design Review (and it was the cover story.) Richard Geary, a great admirer of Rudolph, wrote the text; and Ed Chappell did the photographs. The article conveys the sensual-layered composition of the spaces which Paul Rudolph created and in which he lived. Unfortunately, the Florida Design Review is no longer published, but you can still get a copy of that issue here.

A view of the opening spread of an article in an issue of Architectural Digest, in which Rudolph’s Deane Residence is profiled—with photographs by Cervin Robinson.

CERVIN ROBINSON

(1928-) One of the most celebrated of the second generation of great architectural photographers, Mr. Robinson was born in Boston, and started photographing at the age of 12. He attended Harvard University and in the 1950’s worked as an assistant to one of America’s most distinguished photographers, Walker Evans. He has said that “pictures of buildings seem to me as satisfying as pictures of people were frustrating”—and architectural photography became the focus of his long, creative, and prolific career. He traveled widely and has worked in a freelance capacity as a photographer for architects and design magazines since 1958—as well as himself being the author and illustrator of several books. Robinson’s work has been shown in many gallery and museums, including the Brooklyn Museum, the Ammon Carter, and the Philadelphia Museum. His website can be found here.

ROBINSON AND PAUL RUDOLPH: In a career that created some of the most dramatic formal solutions in Modern architecture, Paul Rudolph’s Deane Residence is among the most striking that he designed—famous for its rhythm of polygonal structural frames. Cervin Robinson photographed it for an article in Architectural Digest (with text by the late architect, Frank Israel). This master photographer was able to capture the variety of experiences inherent in this the house’s multi-level organization of overlapping spaces, and complex exterior geometries.

ANNIE SCHLECHTER

Ms. Schlechter says of herself and her work that she is “. . . .a native New Yorker who has been working as a photographer since 2000. Her clients include House Beautiful, New York Magazine, Better Homes & Gardens, Veranda, CN Traveler, The World of Interiors. Her commercial work ranges from hotel groups such as The Bowery Hotel and The Greenwich Hotel Group to designers and architects such as Marianna Kennedy, Chiarastella Cattana, Joe Serrins Studio, Inc Architecture & Design among others.” You can see Annie Schlechter’s splendid work here.

SCHLECHTER AND PAUL RUDOLPH: Ms. Schlechter collaborated with well-known writer Polly Devlin to create a book on amazing interiors in New York City—but, being largely private, these were spaces which the public had rarely or never known about or seen. The result was a book rich in story and color, “New York: Behind Closed Doors". They approached Ernst Wagner, the owner of the Paul Rudolph-designed Modulightor Building, about including it in the book—to which he not only agreed, but he also worked with them to provide the full background story, including Paul Rudolph’s intent for building, as well as Wagner’s reflections on it. Ms. Schlechter has graciously allowed the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation to include her photographs of the building and its interiors on their project page for the Modulightor Building.

The Modulightor Building—as seen in the evening, within its urban context. Photograph © Joe Polowczuk, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation Archives

JOE POLOWCZUK

Among the younger generation of design-focused photographers, those who have a sensibility that makes for great architectural images, is Joe Polowczuk. We may say “younger,”, but to look at his portfolio—which is full of variation in subject and varieties of visual delight—is to see someone with great experience and an exceptional eye for the possibilities of light. You can learn more about Joe, and see a beautiful selection of his work here—and you can read our article about him here (in which you can also see some of the photos he took of the exterior and interiors of Rudolph’s Modulightor Building).

POLOWCZUK AND PAUL RUDOLPH: In 2019, in cooperation with the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, Joe made some luminous photographs of Paul Rudolph’s Modulightor Building, as well as the Rolling Chair that was also designed by Rudolph for use in his own penthouse home.

Ms. Broder captured the sense of deep space and spreading light, within one of the upper floors of the Modulightor Building. Photograph © Anne Broder, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation Archives

ANN BRODER

Anne Broder is a photographer who works both in the professional world, making photographs of interiors with an unerring eye for composition and color, and also uses photography to create moving artistic images of architecture, sculpture, and abstract forms. Of her work, she says “Today, I freelance as a real estate photographer and work the camera for architects, interior designers, retail shops, portraiture and for my own joy of photography.” You can see her beautiful work here.

BRODER AND PAUL RUDOLPH: Ann. Broder had become aware of the light-filled and varied spaces of Paul Rudolph’s Modulightor Building in New York City—a project that Rudolph had commenced in 1988. She approached us about photographing the building, and we were delighted to have Ms. Broder bring her eye and skills for recording this amazing building (especially, but not limited to, the recently finished uppermost floors of the building.)

An interior of Paul Rudolph’s penthouse apartment, in its current state. Photograph © Francis Dzikowski / OTTO, Archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

FRANCIS DZIKOWSKI

Mr. Dzikowski writes of his himself and his work that he “. . . .attended Virginia Polytechnic Institute’s foundation program in architecture and studied photography at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia Pennsylvania. He spent a decade living and traveling abroad photographing historical restoration projects and archaeological excavations. While photographing in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings for the Theban Mapping Project, Francis also taught photography at the American University in Cairo. He currently lives in Brooklyn, New York working as an architectural and interiors photographer. In 2009 he completed publication of a book titled, Public Art New York. . . .” You can see his work here, and learn more abut his book here.

DZIKOWSKI AND PAUL RUDOLPH: Paul Rudolph’s own home in New York City, his “Quadruplex”, has been photographed at various times over the decades. But it has been relatively inaccessible in recent years—so it was a great delight when the building’s current owners allowed the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation to visit it at the beginning of 2020. Francis Dzikowkski was present during that visit, creating a vivid portfolio of images to document the current state of that fascinating set of spaces.

A middle-distant view of a side elevation of the Burroughs Wellcome building, stately sitting within North Carolina’s landscape. Photograph © PJ McDonnell, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation Archives

P. J. McDONNELL

Mr. McDonnell, who is based in North Carolina, says of himself: “I am a photographer, originally from New Jersey. I came across the Burroughs Wellcome building while browsing maps of the Research Triangle. Learning about the building is what sparked my interest and appreciation for Paul Rudolph's work.” You can see more of his photography—which certainly displays his strong interest in architecture, but which also embraces other visually fascinating subjects—on his Instagram page, here.

McDONNELL AND PAUL RUDOLPH: We came to really appreciate the work of P. J. McDonnell during our current campaign to save the Burroughs Wellcome building in North Carolina. The building had been the US headquarters and research center of the pharmaceutical giant, but it is now under threat of demolition. While the most familiar and frequently published published images of the building show it pristine and new, P. J. McDonnell’s photographs—made much more recently—show it in its current state. These powerful images share with us a building which, while needing work, also shows that great architecture can always maintain its power and dignity. McDonnell states “Like all of his work, the Burroughs Wellcome building is otherworldly, awe inspiring, and a one-of-a-kind building that could never be replaced.”

Rudolph And His Architectural Photographers — PART ONE

A compelling photo by G. E. Kidder Smith of Paul Rudolph’s Burroughs Wellcome US headquarters and research center, shown near the time of the building’s completion. Here, the photographer gives us an image which simultaneously captures the architecture’s play of volumes, structural and geometric adventurousness, aspects of its siting, and scale. Photo courtesy of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

PHOTOGRAPHIC POWER

What’s more important: a great building -or- a great photograph of it?

It’s an impossible question to answer—not because of its difficulty, but rather: because the question itself attempts to compare such different entities. The “actuality” of architecture—the way one would come to know a building, in-person, by entering and moving through it and experiencing the spaces sequentially (truly a four-dimensional phenomenon), and also through other senses (sound and touch)—is wholly different from the way that one takes-in the information embodied in a two-dimensional photograph.

Then how are architectural photographs important?

The answer: in their potential for influence.

ENDURING AND WIDESPREAD INFLUENCE

No matter how many people see a building in-person, an uncalculable greater number can see it in photographs—-and those viewings continue onward, even if the building ceases to exist.

Probably the most famous case is Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion. It was built for a 1929 international exposition, and—from the time of its inauguration-to- its demolition—it only existed for less than a year. Since then, it has been known from a handful of photographs and its plan.

Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion, was built in 1929 and demolished within the following year. Of the handful of photographs recording what it looked like when extant, this is probably the most famous image.

Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion of 1929 was built for an international exposition. It is preponderantly known only through a handful of photographs and two drawings (the plan, above, and a detail of a typical column.) Yet on the strength of this small group of images, it gained—and retains!—world-class status as one of the ultimate icons of architectural Modernism.

Of that small group of photographs, the most famous image is probably the one shown above. Those photos, combined with the plan drawing, have been included in countless books, articles, lectures, curricula—-and, even more important: they’ve become integrated into the thinking of every Modern architect. [We’ve written here about Rudolph’s own interest in the Barcelona Pavilion, and also here about his relationship to Mies’ work.] Now, coming-up on a century since it’s demolition, this iconic building continues to resonate through architectural education, scholarship, and practice— mainly because of photographs.

Further: try as we may to visit the great, iconic examples of architecture, they are just too dispersed. So even a devoted architectural traveler could spend decades just trying to see most of them. So, practically speaking, we have to experience and learn about most of of the world’s architecture from photographs.

THE GREAT PHOTOGRAPHERS OF MODERN ARCHIECTURE—CREATING THE ICONS WE REMEMBER

The 20th and early 21st centuries have been graced with architectural photographers that can be considered “artists-in-their-own-right”. That’s because they’ve not only been able to capture the formal essence of architectural works, but—like visual alchemists—they have also created images which (through their choices of point-of-view, lighting, focus, and composition) have virtually created the vital identities of those buildings.

Prime examples would be the powerful photo that Ezra Stoller took of Paul Rudolph’s Yale Art & Architecture Building—it’s the image we “have in our head” when we think of the building; Yukio Futagawa’s chroma-rich capturing of the interior of Rudolph’s Tuskegee Chapel; and Balthazar Korab’s photos of the soaring wings of Saarinen’s TWA “Flight Center” terminal at Kennedy Airport. To many of us, those images are the building.

Ezra Stoller’s photograph of the exterior of Paul Rudolph’s Yale Art & Architecture Building became the iconic image of it—and it’s included on the cover of his book on that famous building.

Each issue of Futagawa’s journal, GA (Global Architecture) focused on one or two buildings. This one is on Rudolph’s Tuskegee Chapel and Boston Govt. Service Center—and Tuskegee is on the cover.

Balthazar Korab photographed a number of designs by Eero Saarinen, including the TWA terminal for Kennedy airport. His photographic work on that project ranged from recording the Saarinen office’s working models, to construction photos (like the one above), to the finished building. Even in its construction stage, when it was only raw concrete, Korab was able to capture the drama of the building. Photo courtesy of the Balthazar Korab Photographic Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

RUDOLPH AND HIS PHOTOGRAPHERS

Paul Rudolph worked with some of the century’s greatest architectural photographers—the ones who are celebrated for working with the leading figures in the world of architectural Modernism. While Rudolph might have been directly involved with some photographers—commissioning them, or requesting that they focus on certain aspects of a building—in other cases, even without Rudolph’s involvement, great photographers have been engaged (by others) to shoot his work; or have done so just out of their own interest in his oeuvre.

While not exhaustive, we’ll review a round-up of many of the photographers who have been focused on the work of Paul Rudolph—and we’ll do this in two parts:

PART ONE (this article) looks at the great architectural photographers of the early-to-late 20th Century, who have worked on Rudolph’s oeuvre.

PART TWO will look at photographers—most still very active—who have more recently focused on Rudolph’s work.

EZRA STOLLER

(1915-2004) When one thinks of architectural photography in America, the name—or rather: the images—of Ezra Stoller are what probably first come to mind. For decades, he photographed many of the 20th Century’s most significant new buildings in the US (by the country’s premier architects), thereby creating an archive of the achievements of Modern American Architecture. More than that, Stoller’s views are some of the most iconic images of that era.

STOLLER AND PAUL RUDOLPH: Of the several photographers that Rudolph worked with, Ezra Stoller is probably the one with which he had the most involvement and lasting relationship. Stoller photographed much of his residential work in Florida—including some of Rudolph’s greatest and most innovative houses like the Milam Residence (as seen on the over of Domin and King’s book on the Florida phase of Rudolph’s career—see image at right), the Walker Guest House, the Umbrella House, and the Healy “Cocoon” House—the Yale Art & Architecture Building in New Haven, Sarasota Senior High School, the Temple Street Parking Garage in New Haven, Endo Labs, the UMass Dartmouth campus, Tuskegee Chapel in Alabama, the Hirsch (later: “Halston”) townhouse in New York City , the Wallace House, Riverview High School in Florida, the Sanderling Beach Club in Florida, and numerous others—including the Burroughs Wellcome US headquarters and research center in North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park. One can access the extensive and fascinating archive of Ezra Stoller’s work (including the Rudolph projects that he photographed) here—and an extensive selection from throughout Stoller’s career (including numerous images of Rudolph’s work) can be viewed in the book “Ezra Stoller, Photographer” (see cover at right).

The first monograph on Rudolph which featured extensive color photography, all of which was done by Futagawa.

YUKIO FUTAGAWA

(1932-2015) The dean of architectural photography in Japan, and with a world-wide reputation, for over six decades Futagawa made magnificent and memorable photos of important buildings (new and traditional) around the world. Interestingly, he created his own “platform” to publish his work: he founded GA (“Global Architecture”), GH (“Global Houses”), and published other series and individual books. Those contained not only of photography, but also architectural drawings and full project documentation of distinguished works of architecture.

FUTAGAWA AND PAUL RUDOLPH: Futagawa traveled the US to make the photographs for the monograph, “Paul Rudolph” (part of the Library of Contemporary Architects series published by Simon and Schuster)—and the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation posseses a note by Rudolph, testifying to his appreciation of Futagawa’s work. In the GA series, he published one on the Tuskegee Chapel and the Boston Government Service Center. Futagawa extensively photographed the work of Frank Lloyd Wright and, as part of the GA series, he asked Rudolph to contribute the introductory essay to the issue on Wright’s Fallingwater. He also published the large monograph on Rudolph’s graphic works (copiously including his famous perspective drawings): Paul Rudolph: Architectural Drawings.

Kidder Smith’s two-volume “A Pictorial History of Architecture in America,” published in 1976, includes Rudolph’s work. Below: one of his photographs of the Niagara Falls Central Library, taken near the time of its completion. Photo courtesy of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

G. E. KIDDER SMITH

(1913-1997) Along with the other ultra-prominent names we’ve been mentioning, in the world of architectural photography, we must include G. E. (George Everard) Kidder Smith. Trained as an architect, Kidder Smith was not only a photographer of architecture, but also an historian-writer, exhibit designer, and preservationist (helping to save/preserve the Robie House and the Villa Savoye.) His numerous books are still important resources for anyone doing research on the architecture of America and Europe His series of “Build” books (“Brazil Builds” “Italy Builds” “Switzerland Builds” “Sweden Builds”) provide abundant images and information about the rise of Modern architecture in each of those countries.

KIDDER SMITH AND PAUL RUDOLPH: Kidder Smith’s “A Pictorial History of Architecture in America” is a 2-volume work that was published in 1976, and—utilizing the photographs that Kidder Smith had made—it covers all eras of American architectural history, region-by-region. Kidder Smith must have admired Paul Rudolph’s work, for it shows up throughout this major, encyclopedic work, and includes: Rudolph’s Boston Government Service Center, Tuskegee Chapel, Niagara Falls Central Library, UMass Dartmouth, the Orange County Government Center—and Burroughs Wellcome (whose double-page spread image is the photographic climax at the end of Volume One.). This set of buildings are of particular poignance and and meaning to us, as they include a major Rudolph building that has been altered/disfigured (Orange County); and three which are currently threatened (Boston, Niagara Falls, and Burroughs Wellcome.)—and we are using Kidder Smith’s images to help fight for their preservation.

This monograph from 1984 shows work from the several generations of photographers who have worked for Hedrich-Blessing, and the book includes an image of Paul Rudolph’s Christian Science Student Center. An even larger monograph of Hedrich-Blessing’s work was published in 2000, which also included that photo of Rudolph’s building.

HEDRICH-BLESSING

(1929-Present) The other photographers of Rudolph’s work, mentioned in this article, were primarily based on or towards the US’ East Coast. But for the middle of the country, the kings of architectural photography were Hedrich-Blessing. The firm was founded in 1929 by Ken Hedrich and Henry Blessing and—though based in Chicago and famous for photographs of buildings in that region—they have done work all over. Among the distinguished architects, whose work they photographed, were: Wright, Mies, Raymond Hood, Keck and Keck, Albert Kahn, Adler & Sullivan, SOM, Harry Weese, Breuer, Saarinen, Gunnar Birkets, Yamasaki, and Alden Dow. Since its founding, the firm has employed several generations of photographers, and is still very much active today.

HEDRICH-BLESSING AND PAUL RUDOLPH: To our present knowledge, Hedrich-Blessing did not photograph many of Paul Rudolph’s buildings. [Perhaps because Rudolph did not build much in their part of the country. That may have been different had Rudolph become dean of IIT’s School of Architecture in Chicago—an offer he briefly considered.] We do know of at least one superb photo Hedrich-Blessing took of his Christian Science Student Center. This building, which Rudolph designed in 1962 near the University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana, was unfortunately demolished in the mid-1980’s. So it is important that we have Hedrich-Blessing’s photograph, which was taken by their staff photographer Bill Engdahl in 1966: it shows the building at night: dramatically shadowed on the outside, but enticingly glowing from within.

Above: Shulman’s extensive oeuvre is documented in a three-volume monograph published by Taschen. Below: One of Shulman’s photographs of Rudolph’s Temple Street Parking Garage. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10)

JULIUS SHULMAN

(1910-2009) Shulman was an almost exact contemporary of some of the other legendary architectural photographers on this list (i.e.: Stoller and Kidder Smith), and his professional career extended over 7 decades—from the 1930’s into the 2000’s. The body of work for which he is most well known is the large set of photographs he took of Modern architecture in California—centered in Los Angeles, but extending to cover buildings in other parts of the state. His clients included some of the most famous makers of Modern architecture: Pierre Koenig (for whom he took a night time photo of the Stalh House which became the iconic emblem of modern living in Southern California,) Neutra, Wright, Soriano, the Eames, and John Lautner. Christopher Hawthorne, of the Los Angeles Times, said of his work: “His famous black-and-white photographs. . . .were not just, as [Thomas] Hines noted, marked by clarity and high contrast. They were also carried aloft by a certain airiness of spirit, a lively confidence that announced that Los Angeles was the place where architecture was being sharpened and throwing off sparks from its daily contact with the cutting edge.” Shulman also had commissions in other parts of the country, as in: his photographs of Lever House in New York, a house by Paolo Soleri in Arizona, and work by Mies in Chicago—and he worked internationally, for example: photographing a residence by Lautner in Mexico. He authored 7 books, participated in 10 others, and his extensive archive is in the Getty Research Institute.

SHULMAN AND PAUL RUDOLPH: While Julius Shulman is identified with the photography of key examples of architectural Modernism in California, he also took assignments for other locations, and his images of Paul Rudolph’s works in New Haven are strong examples of Shulman’s image making. Several can be seen on the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s project pages for the Temple Street Parking Garage, and the Yale Married Students Housing. The photographs of the garage are intense with visual drama, highlighting its scale and sculptural qualities.

Above: Molitor’s photo of UMass Dartmouth. Below: Niagara Falls Central Library. Images courtesy of Columbia University, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Joseph W. Molitor Photograph Collection

JOSEPH W. MOLITOR

(1907-1996) We are fortunate that the the Joseph W. Molitor Photograph Collection is now part of the Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, where it is made available to scholars, researchers, writers, and students. The Avery Library describes Molitor and his career: “Joseph Molitor, recognized as a peer of such leading 20th-century American architectural photographers as Hedrich-Blessing, Balthazar Korab, Julius Shulman, and Ezra Stoller, documented the work of regional and national architects for fifty years. Trained as an architect, he practiced for twelve years before briefly working in advertising. Molitor turned exclusively to architectural photography in the late 1940s, maintaining his studio in suburban Westchester County, New York. Working primarily in black and white, Molitor's images appeared in Architectural Record, The New York Times, House & Home, and other national and international publications.”

MOLITOR AND PAUL RUDOLPH: Avery’s text also mentions “His iconic photograph of a walkway at architect Paul Rudolph’s high school in Sarasota, Florida, won first place in the black and white section of the American Institute of Architects’ architectural photography awards in 1960.” You can find Joseph Molitor’s photographs on several of the project pages within the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s website, including the pages devoted to the Milam Residence in Florida, and the Niagara Falls Central Library—and his book, Architectural Photography, published in 1976, features an abundance of images of Rudolph’s work. Recently, the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation has been focused upon Molitor’s work because of the endlessly intriguing set of photographs he made of the Burroughs Wellcome building—showing them with a crispness and sense of drama that few other photographers have approached.

Above and Below: two of Henry L. Kamphoefner’s photographs of interiors within the Burroughs Wellcome building in North Carolina—both images displaying the striking geometries which Rudolph used in the design.

HENRY L. KAMPHOEFNER

(1907-1990) Unlike the above figures, Henry Leveke Kamphoefner is not primarily known as an architectural photographer—but he was well-known in the South as a champion of Modern architecture, especially in North Carolina. Graduating from the Univ. of Illinois with a BS degree in architecture in 1930, in the following years he received a MS in architecture from Columbia and a Certificate of Architecture from the Beaux Arts Institute of Design in New York. From 1932 until 1936, he practiced architecture privately, and one of his most well-known works is a municipal bandshell Sioux City (which was selected by the Royal Institute of British Architects as one of "America's Outstanding Buildings of the Post-War Period.") In 1936 and 1937, he worked as an associate architect for the Rural Resettlement Administration, and during summers after that he was was employed as an architect for the US Navy. He had an ongoing and significant involvement with architectural education: in 1937 he became a professor at the Univ. of Oklahoma and during 1947 was also a visiting professor at the Univ. of Michigan. In 1948 Kamphoefner became the first dean of the North Carolina State College School of Design, creating strict admissions policies and instituting a distinguished visitors program which brought in architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright. He remained dean until 1973, but continued teaching until 1979. From 1979 to 1981 he served as a distinguished visiting professor at Meredith College. Kamphoefner’s importance has been highlighted in a new book, Triangle Modern Architecture, by Victoria Ballard Bell.

KAMPHOEFNER AND PAUL RUDOLPH: The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation has included several of Kamphoefner’s photographs of the Burroughs Wellcome US headquarters and research center on its project page for that building. It is natural that, as a resident of North Carolina, and as an advocate for Modern architecture, that he would be focused on that building. His photographs of the interiors highlight the striking diagonal geometries that Paul Rudolph incorporated into the project. We have included his images of Burroughs Wellcome in several of our blog articles, as part of our fight to preserve this great work of architecture.

COMING SOON: PART TWO

Be sure to look for PART TWO of this study of Paul Rudolph And His Architectural Photographers. It which will look the more recently active photographers, each of whom have focused on the work of Paul Rudolph.

Ernst Wagner: Fighting to Preserve the Legacy of Paul Rudolph

Paul Rudolph's "Pyramid of Power" (Texas Style)

A night-time rendering of Paul Rudolph’s Channel 7 TV station headquarters building, designed for Amarillo, Texas.

The most well-known builders of pyramids were the Egyptians and several Mesoamerican civilizations—and even the Romans had one!

Pyramidal structures can be found in other parts of the world—from Indonesia to China to Greece (and now Las Vegas).

But Texas too?

Yes—via Paul Rudolph’s design for the headquarters of a TV station in Amarillo, Texas—a project of his from 1980. For a long time, the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation had very little information on this building: we knew it was commissioned by Stanley Marsh—one of Amarillo’s lively characters and a patron of the arts—and we had an address for the building, and Rudolph’s intriguing rendering (which shows it at night, with an array of lights blazing upwards from the center.) We still don’t know much about the commission—it will bear further research—but we do have some fresh images to share.

The building—its formal name and address being “1 Broadcast Center”—is still the home of KIIV, Channel 7—the ABC/CW+ station in Amarillo. KIIV has a long history in Amarillo, having first signed on-the-air in 1957.

The context for the building:

A satellite view of the neighborhood where the pyramidal TV station is located in Amarillo, Texas. North is towards the top, and the building’s roof is marked by the red arrow. Amarillo’s Elwood Park is at the far left, and railroad lines are at the right edge of the photo. The several forking roads, which merge towards at the bottom of the picture, converge to form US Highway 287. Image courtesy of Google: Imagery ©2019 Google, Imagery ©2019 Maxar Technologies.

A closer-in satellite view, looking down on the TV station’s pyramidal roof:

To get a sense of the building’s scale, one can compare it with the cars which are parked to the North, East, and South. At the bottom of the picture (at the South, just below the line of parked cars) is an array of the numerous types of antennas used by the station. Image courtesy of Google: Imagery ©2019 Google, Imagery ©2019 Maxar Technologies.

Ben Koush, AIA, is a registered architect, interior designer, and writer, based in Houston, Texas. He has a strong interest in history, and—fortunately for us—is also a photographer. You can see numerous examples of the images he’s captured on his Instagram page—and he’s given us permission to share the ones he’s taken of Rudolph’s TV station:

Front view of the Eastern side of the TV station building: KVII, ABC’s Channel 7 in Amarillo Texas, designed by Paul Rudolph. Photo © Ben Koush, used with permission.

A diagonal view. As in Rudolph’s rendering, the Channel 7 logo (and name of the staton) is prominent at the pyramid’s apex. Photo © Ben Koush, used with permission.

A view of the South side, with the station’s many antennae in the foreground. Photo © Ben Koush, used with permission.

A view from below the pyramid’s roof. The steel structures appears to support an open mesh sheathing, and the enclosed body of the building seems to be composed of a metal & glass curtain wall system. Photo © Ben Koush, used with permission.

Scott Fybush, based in Rochester NY, has also allowed us to show his photo of the building. Mr. Fybush has professional experience across all facets of broadcasting, and, under the Fybush Media banner, provides consulting services including signal expansion strategy, allocations, FCC filings and station brokerage. Here’s an image he shared with us—with Texas’ “big sky” clouds forming a dramatic background:

The station, as seen from the North. Image courtesy of Scott Fybush.