The photo and signature page from Paul Rudolph’s US passport, issued in 1954. Rudolph was 35 at the time, and the home address he’s written into the passport indicates that he was then a resident of Sarasota. From the collection of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

The extent to which an architect needs to travel, has rarely been focused upon. Yet if one is an active professional, then you’re constantly traveling:

to meet potential and current clients (and to keep meeting with them during the design and construction phases of a project)

to view (and sometimes help in the selection of) sites where construction is to take place

to be present at meetings with the area’s various boards, committees, and inspectors

reviewing the work of prospective contractors

to visit projects during construction

visiting sub-contractors—especially craftspeople and artists—at their studios or shops, to review the form, detail, process, and progress of custom-built items

and—finally and hopefully—to be there during the dedication ceremony!

Add to these the other kinds of activities which add to many architects’ travel schedules:

lecturing

teaching and/or serving on juries

attending conventions

professional continuing education classes

trying to visit, nationally and world-wide, the key monuments of architecture (another kind of self-education)

To some, all this travel is largely a pleasure. To others, it becomes a kind of trap: one finds oneself in an endless round of far-flung appointments, without a sense of ever arriving “home” (nor having the quiet time necessary to really think-through a project’s design challenges.) And it can be energy draining: when a young staff member expressed envy of his boss—a consultant with an international practice—about all the travel he got to do, we heard him respond: “You’ll feel that way—until you start doing it yourself!”

Rudolph, from what we can tell, embraced travel—or at least had to, in order to accomplish his career goals. Wilder Green, an early employee of Rudolph, worked in his Florida office for a year in the early 50’s—a time when Rudolph had already established himself as a residential architect, but was seeking to expand the kinds of commissions he was receiving (so as to explore other building types.) In a 1991 interview with Sharon Zane, Green recalls:

WG: . . . In June of '52 I went to Sarasota, Florida, and worked for Paul Rudolph for a year. I was the only person in the office. He had an office about two thirds of the size of this room, and he lived at the back of it. Almost the day I arrived, he left to teach somewhere and left the office in my hands, practically. So it was marvelous training, but it was kind of a baptism by fire. I learned a lot in that year--in the scale of what he was building, which wasn't that big.

SZ: What was he building at that time?

WG: He was building houses primarily, but not exclusively. He was building several houses but he was also gradually getting involved in small office buildings and he was also working on a kind of a marine mini Disneyland structure in Florida. He was very active in teaching at Pennsylvania and Yale.

SZ: That was a lot of traveling he had to do.

WG: All the time. He was trying to get out of Florida as much as he could.

SZ: What was he like to work for?

WG: Very high-strung, ambitious, brilliant, in many ways unsure of himself I think would be the best way to describe him. He had a very short fuse, and yet, if you did something right he definitely gave you credit, he was appreciative. He had a complex combination of human characteristics, but he was extremely talented, and I learned a lot from him.

So we see, from even early in Rudolph’s career, travel was involved both for work and teaching.

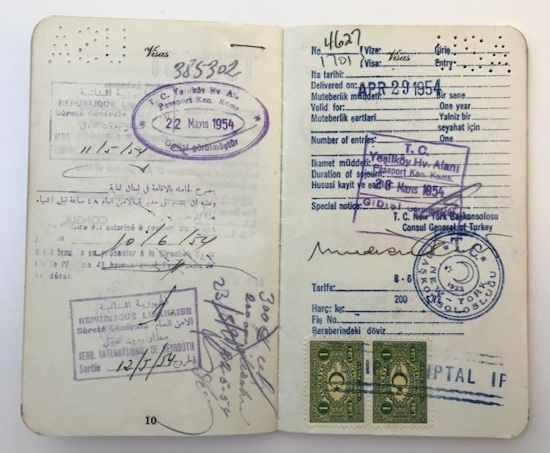

Not too long before, Rudolph had seen Europe for the first time, through receiving Harvard’s Wheelwright Prize for travel (he was there from mid-1948 -to- mid-1949)—a life-changing experience. And he continued to travel internationally. Here are some pages from his US passport (the one issued to him in 1954)—and one can see evidence of his international treks from the passport stamps:

Of course, in addition to work, there are all kinds of pleasures from travel. Rudolph was a great collector, and wherever he traveled picked-up objects—even occasionally real antiquities—that pleased his eye. Sometimes such acquisitions came about through serendipity, as in these washboards from Japan:

These wooden washboards, from Japan, all have slightly different forms. They are on display in the Paul Rudolph-designed duplex within the Modulightor Building. From the collection of Ernst Wagner.

As further evidence of Rudolph’s embrace of travel—unto the end of his life—is this item. In the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation is a small, red, hardcover ledger book:

It is labeled: “Travel Book 1990, 1991”

It records Rudolph’s travels and appointments from January 1, 1990 -to- December 6, 1991. While looking at it, the thing to remember is that Rudolph is well over 70 years old when this record was made—yet the book shows the great distances he’s still traveling, and frequently, mainly for work (and this is only the example what he’s doing in a single year):

Boston

Dallas-Fort Worth

Amarillo

San Francisco

Bangkok

Singapore

Hong Kong

London

Jakarta

Sydney

Perth

Istanbul

Rome

And, especially to meet his clients in Asia, he wasn’t going to to these locations just once: the record shows him going numerous times.

Interspersed with all this air-travel, to-and-from New York City, is shown his many appointments in the New York area—both professional and social—meetings, lunches, or dinners with people who are integral to his practice & life: Mrs. Bass, Emily Sherman, Ron Chin, Errol Barron, Bert Brosmith, Carl Black, George Ranalli, the Edersheims, George Beylerian, Ezra Stoller… and many others (plus giving lectures at Pratt and Harvard.)

Here are a few sample pages:

You can imagine what a travel and meeting schedule like this would do to anybody—and the wear-and-tear to any human body. But one thing we can say for certain about Rudolph: He was determined.

An example of Paul Rudolph’s luggage. The layers of airport inspection stickers testify to his endless travel. From the collection of Ernst Wagner.