The Biggs Residence—a Rudolph design of 1955-1956, in Delray Beach, Florida—has just now been demolished. It is pictured here from the time it received a Merit Award in the 1959 Homes for Better Living Awards sponsored by the AIA.

AN ACCELERATING RATE OF DESTRUCTION

The Burroughs Wellcome headquarters building and research center, in Durham, North Carolina—one of Paul Rudolph’s most iconic designs, and a structure of historic importance—has been turned into demolition debris.

In the last several years, it seems like we’ve experienced an acceleration in the destruction and threats to our architectural heritage—and this has hit the works of Paul Rudolph especially hard. Several important Rudolph buildings are now threatened, or have been outright destroyed or removed—and they are some of Paul Rudolph’s profoundest, key works:

Burroughs Wellcome: DEMOLISHED

Walker Guest House: REMOVED—taken apart, and moved to an unknown location

Orange County Government Center: DEMOLISHED—partially, with the balance changed beyond recognition

Niagara Falls Main Library: THREATENED

Boston Government Service Center: THREATENED

Milam and Rudolph Residences: SOLD -or- ON THE MARKET—with no assurances that new owners won’t demolish or change them beyond recognition

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation advocates for the preservation and proper maintenance of buildings designed by Rudolph—and is available to consult with owners about sensitive adaptive reuse, renovation, and redevelopment of Rudolph buildings (especially as an alternative to demolition!)

But, vigilant as we are, sometimes we’re taken aback by news of a precipitous demolition or marring of one of Rudolph’s great designs.

THE LATEST DESTRUCTION OF A RUDOLPH BUILDING

The opening of Mike Diamond’s article about the demolition of the Biggs Residence, which appeared in the March 12, 2021 issue of the Palm Beach Post.

We’re shocked that yet another of Paul Rudolph’s fine works of architecture has been demolished—and, if the news report is accurate, it’s been allegedly done without even a permit.

The Biggs Residence is a Rudolph-designed residence in Delray Beach, Florida, from 1955-1956. Over the years, the subsequent owner or owners have not been kind to it: there have been numerous and highly conspicuous changes and additions which cannot be called sympathetic to Paul Rudolph’s original design. New owners have, in the last few years, been planning to remove the offending changes and accumulated construction—and have been lauded for their good intentions. Repairs and restorations were to be done, as well as alterations and additions that were to be sympathetic to the building (and be resonant with Paul Rudolph’s approach to planning and construction.) Plans were filed, and the owner’s architect—an award winning firm—produced a well-composed “justification statement” which offers some interesting and convincing thinking about how they intended to proceed with the project, their design strategies and solutions, and how they were to have the property “rehabilitated.”

But—

But, according to March 12th article in the Palm Beach Post, much more has actually happened at the site. Their reporter, Mike Diamond, reports that the current owners “. . . .were found to have violated the city’s building code by demolishing the house without a permit from the city’s Historic Preservation Board.”

This site photo shows that, as of the moment it was taken, some of the Biggs Residence’s structural steel was still in place—but most of the rest of the house (exterior and interior walls, windows, ceilings, finishes, cabinetry, fittings…) has been demolished and removed.

The article further says that the owners “. . . .must obtain an after-the-fact demolition permit. . . . They also face steep fines for committing and ‘irreversible’ violation of the city’s building code.” The owners are disagreeing, and claiming that the city misinterpreted their documents and, in the article’s words, their lawyer claims that “. . . .the city should have realized that the approvals for renovation could have resulted in the house being demolished based on its deteriorating condition….”

That is a claim which an attorney for the city and a city planner both dispute.

SERIOUS QUESTIONS

Perhaps there were good reasons for the owners to proceed this way—but there are serious questions:

What were their compelling reasons?

What were the building’s actual conditions, which led them to decide for demolition?

What alternatives were considered?

Could there have been other approaches?

What did the architect think of this decision to demolish?

No doubt, there will be further developments in this case, and we will be following it.

PAUL RUDOLPH’S DESIGN AT tHE BIGGS RESIDENCE: PURITY OF CONCEPT

The Biggs Residence was—and now, unfortunately, we’ll have to speak of it in the past tense—an important part of Paul Rudolph’s oeuvre. There he continued exploring several design themes he’d been working on, ever since he’d returned from service in World War II and restarted practice in Florida—and at Biggs, perhaps, he brought one of those themes to its most perfect realization.

Rudolph’s perspective rendering for the Biggs Residence—a drawing which shows his original platonic intent: a pure “rectangular prism” floating above the ground.

Illustrations from Le Corbusier’s manifesto, “Vers une Architecture” (“Towards An Architecture”), in which he speaks of the compelling beauty of pure forms.

As you can see from Rudolph’s perspective rendering (above-left), his conception was quite “platonic”: he was intent on creating a pure form, “floating” above the earth, and tethered to it as lightly as possible—in this case, by an open staircase and a few slender uprights. Even the service block (presumably to contain or screen the boiler, and maybe an auto,) sheltering below, was fully detached from the prime living volume. Such a conception (and goal) comes out of one of the root obsessions of the Modern movement in architecture: a kind of purism which is animated by a love of geometric forms, and which eschews all that might obscure that purity. Le Corbusier, in his foundational book, “Vers une Architecture” (“Towards An Architecture”) puts it boldly:

“Architecture is the masterly, correct and magnificent play of masses brought together in light. Our eyes are made to see forms in light; light and shade reveal these forms; cubes, cones, spheres, cylinders or pyramids are the great primary forms which light reveals to advantage; the image of these is distinct and tangible within us without ambiguity. It is for this reason that these are beautiful forms, the most beautiful forms. Everybody is agreed to that, the child, the savage and the metaphysician.”

Of course, interest in (and obsession with) such “pure” geometric forms goes back to the ancients (i.e.: the term “platonic”), and even in the 18th century—a time when classical architecture was dominant, including its full ornamental armamentarium—architects like Claude-Nicolas Ledoux and Étienne-Louis Boullée produced visionary drawings of architectural projects that embraced such purity (with perhaps the most famous being Ledoux’s design for a spherical villa.)

Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s view of a spherical country house. He fully developed the design, including plans and sections.

Paul Rudolph, born during Modernism’s heroic years. was educated by the founder of the Bauhaus himself, Walter Gropius (who was head of the architecture program at Harvard while Rudolph was a student there). He could not have helped being immersed, taught, and saturated in such aesthetic ideals—and he brought them into his work.

Looking at Rudolph’s oeuvre, we can see that he tried this platonic approach to residential design prior to Biggs: with the Walker Residence project of 1951—but that remained unbuilt; and the Leavengood Residence of 1950—but that building had a more complex program, and thus many more appurtenances outside of the house’s main body (and it also had visually firmer connections to the ground.) So Leavengood did not approach the platonic ideal anywhere as closely as Biggs.

THE AESTHETICS (AND DRAMATICS) OF STRUCTURE

An view of the interior of the Galerie des Machines, one of the exhibition buildings erected for the 1889 world’s fair in Paris. The architects (headed by Ferdinand Dutert) and the engineers (headed by Victor Contamin) dramatically showed the potentials of steel and iron—both as spanning structure and as an expressive medium. The size of the building can be judged from the figures in the distance.

In the initial decades of Rudolph’s career—given the simplicity of the programs for which he was asked to design, and the often limited budgets—structure was one of the few ways that he could explore the potentials of architectural design, and he fully used it as an expressive tool. Whether by doubling vertical members (as he did at the 1951 Maehlman Guest House and the 1952 Walker Guest House), or by using a dramatic suspended catenary roof system (as at the 1950 Healy (“Cocoon”) Guest House), or anticipating the utilization of curved plywood for structural roof arches (as at the 1951 Knott Residence project), Rudolph was always looking at ways to transcend structure’s function, and raise it to the poetics of design.

Certainly, this expressive use of structure has always been a concern of architects, from Gothic cathedral builders to the creators of the titanic structures of iron and steel which emerged during the 19th Century (especially in France, England, and the US).

The “masters” of modernism—having abandoned expressive styles, modes, and motifs available to previous generations—often turned to using structural systems as an important part of their architectural palette, and they did so in inventive ways. Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House ((1945-1951) is an icon of Modern architecture and residential design—and one of the most notable aspects of his design is the relationship he set-up between the planes of the floor and roof, and the building’s vertical steel columns. The columns are, or course, supporting elements—yet Mies plays with their role, having them visually slide past the floor and roof’s perimeter steel members. This confers a partially floating quality to those planes—possibly one of Mies’ prime goals. [It’s also notable that Philip Johnson, at his Glass House (1947-1949), took yet another direction with these relationships. He placed the vertical steel structural members inside the house’s volume, and integrating them with the frames which held the walls of glass—and thus absorbed the structure into the design of the building’s envelope.]

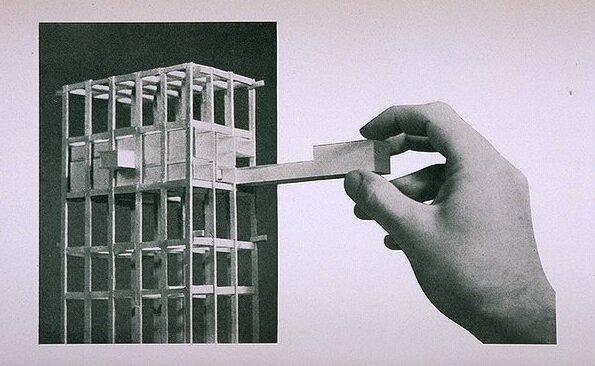

The eyes of the architectural world were on Mies’ design (and Johnsons!)—and Rudolph would have known them well. At Biggs, in contrast to Mies or Johnson, Rudolph chose to pull the perimeter structural frame noticeably inward from the outer edge house’s main floor volume above. Thus, instead of experiencing the building as a pair of planes (as with Mies), Biggs main living area is perceived as a separate volume (reinforcing its “platonic-ness”), only resting upon the structure. Moreover, instead of placing the beams in an overlapping relationship (as Mies did), he intersects them boldly—and they appear to be penetrating through each other.

LEFT: The Farnsworth House (1945-1951) by Mies van der Rohe. Its vertical steel columns visually “pass by” the floor’s and roof’s horizontal structural steel “C” members. ABOVE: In contrast to the Farnsworth House, the Biggs' steel columns and beams appear to pass through each other.

Not only can this be seen on Biggs’ exterior, but it is experienced on the inside as well: the large ceiling beams, which dramatically span the living room, also have the same interpenetrating relationship to the interior’s steel columns.

Those column-beam relationships did not exhaust Rudolph’s exploration of structure at Biggs. He had one more occasion in which he used exterior steel elements in an intriguing way: When the perimeter beams met at the outside corners, instead of butting them (as would be done in standard steel construction), he mitered them at the corners. [You can see this in an exterior photo below.] In this way, the upper and lower flanges of the steel beams were not just there for their structural role, but—via this mitering connection—their visual power as a pair of parallel planes was revealed.

THE PRACTICALITIES OF COMFORT AND CONVENIENCE

Even with such geometric ideals, structural intrigues, and the other fascinations in which creative architects like Rudolph engage, he was also a very practical designer—and sensitive to his client’s needs. At the point when he received the Biggs commission, he had nearly three dozen constructed projects “under his belt.” So, whatever his interest in building pure forms, his planning of the Biggs Residence included features which the owners would find gracious and practical.

The main (upper) floor contained:

two bedrooms (well separated, providing for excellent spatial and acoustic privacy, and each with a significant amount of closets and its own bath)

a central living/dining area (with large amounts of windows for good cross-ventilation—and the ability to catch breezes from the house’s raised design)

a kitchen adjacent to the dining area (with a wise balance of openness and enclosure)

a broad “storage wall” in the central area—a feature of American post-World War II residential design, pioneered by George Nelson

Paul Rudolph’s floor plan of the upper (main volume) level of the Biggs Residence, exhibiting his practical and gracious sense of planning.

The ground floor was also well thought out, and included:

An exterior sitting area (well shaded from the Florida sun)

A covered parking area (also shielding the car from solar overheating, as well as Florida’s occasional heavy rains)

The entry and stairs (up to the main level)

Additional storage or mechanical space (always useful)

The Biggs living room, in which some segments of the house’s structural steel can be seen—especially the pair of long beams which span the living space.

Another view of the living area—this time, towards the dining table at the end of the room, which sits near the storage wall. At the far right is the entry passage to the kitchen. In this photograph, one of room’s pair of large steel ceiling beams is strongly emphasized.

Raising the body of the building liberates space at the ground level, which is left open for shaded outdoor seating and parking. Structural steel—for the columns, and the inset perimeter and intermediary beams—is exposed, and the connections are composed and detailed with care.

FURTHER DEVELOPMENTS (AND WHAT YOU CAN DO)

We’ll keep looking into the Biggs case, and let you know how this develops.

If you have any information on this situation—or know of any other Paul Rudolph buildings that might be threatened—please contact us at: office@paulrudolphheritagefoundation.org

We can keep you up-to-date with bulletins about the latest developments—and to get them, please join our foundation’s mailing list. You’ll get all the updates, (as well as other Rudolph news.)—and you can sign-up at the bottom of this page.

IMAGE CREDITS

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation gratefully thanks all the individuals and organizations whose images are used in this scholarly and educational project.

The credits are shown when known, and are to the best of our knowledge. If any use, credits, or rights need to be amended or changed, please let us know.

Note: When Wikimedia Commons links are provided, they are linked to the information page for that particular image. Information about the rights to use each of those images, as well as technical information on the images, can be found on those individual pages.

Credits, from top-to-bottom, and left-to-right:

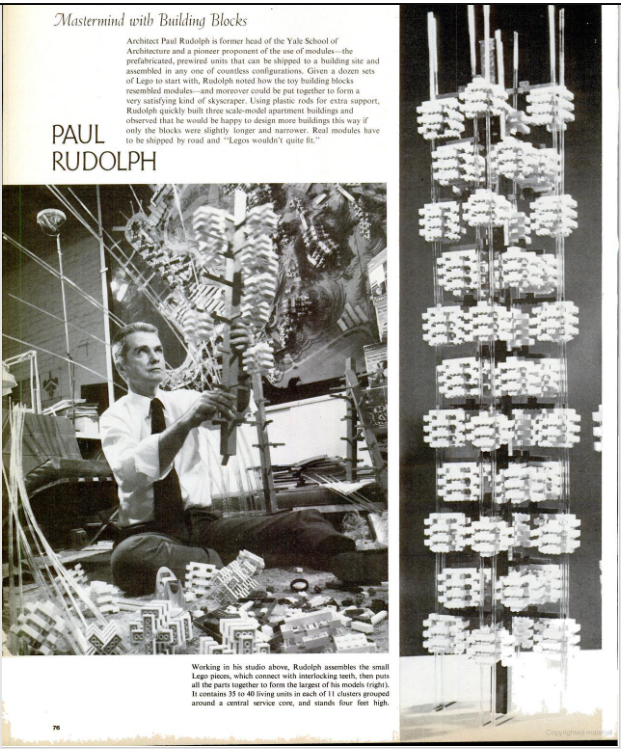

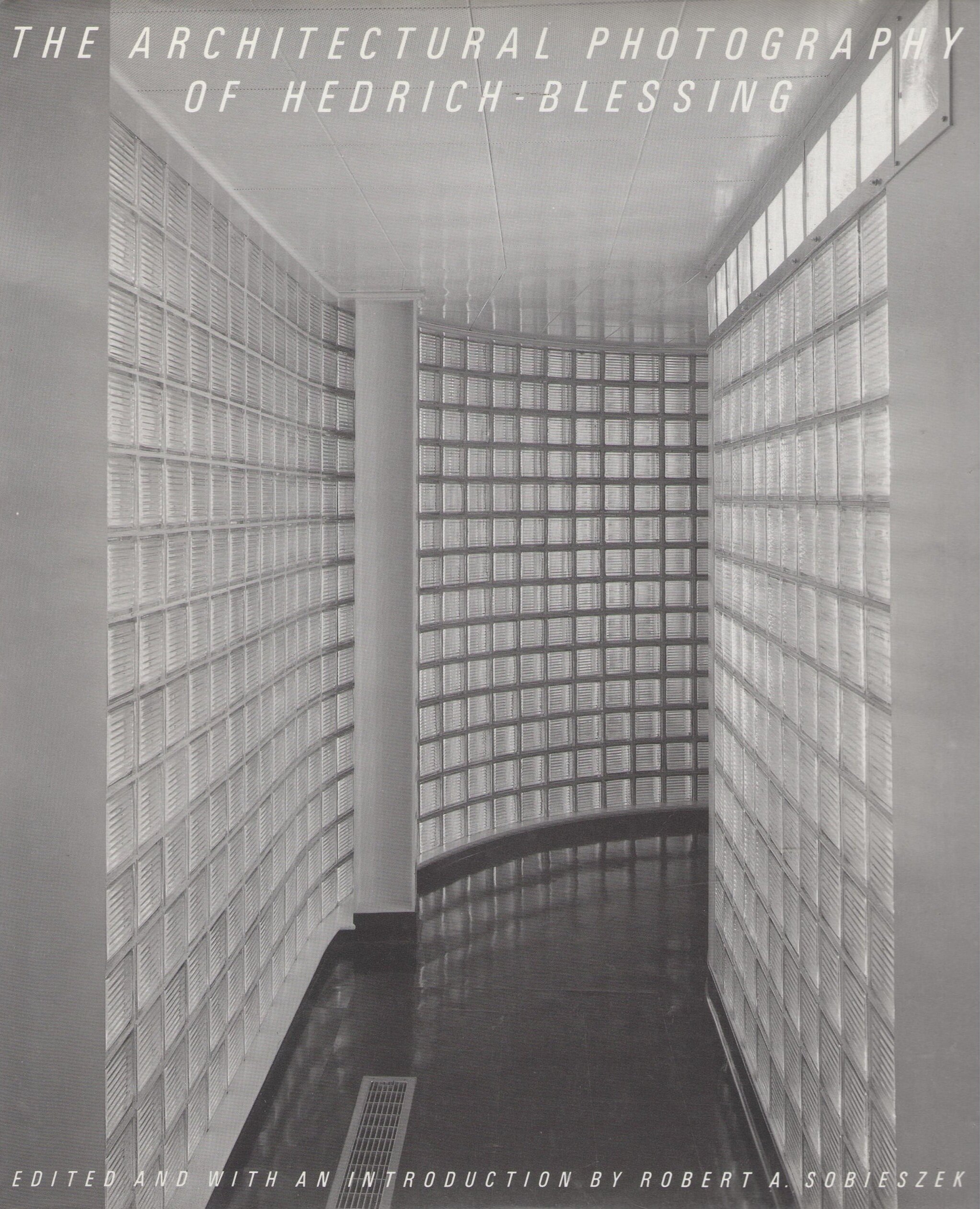

Biggs exterior view: photo by Ernest Graham, from a vintage issue of House & Home magazine, June 1959, courtesy of US Modernist Library; Section-perspective drawing of Burroughs Wellcome building: by Paul Rudolph, © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation; Demolition photo of Burroughs Wellcome building: photography by news photojournalist Robert Willett, as they appeared in a January 12, 2021 on-line article in the Raleigh, NC based newspaper The News & Observer; Perspective rendering of Biggs Residence: drawing by Paul Rudolph, © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation; Mies’ Farnsworth House column-beam relationship: photo by Benjamin Lipsman, via Wikimedia Commons; Plan of Biggs Residence: © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation; Photographs of interiors and exterior of Biggs Residence: photo by Ernest Graham, from a vintage issue of House & Home magazine, June 1959, courtesy of US Modernist Library; Photograph of Paul Rudolph: © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation