Meet Martine Rothblatt, CEO of United Therapeutics. She owns Rudolph’s Kerr Residence in Florida & should be a fan. After promising to preserve it, her company tore down the only Rudolph in NC – the Burroughs Wellcome building in RTP. Now she’s going to lecture on Green Construction…

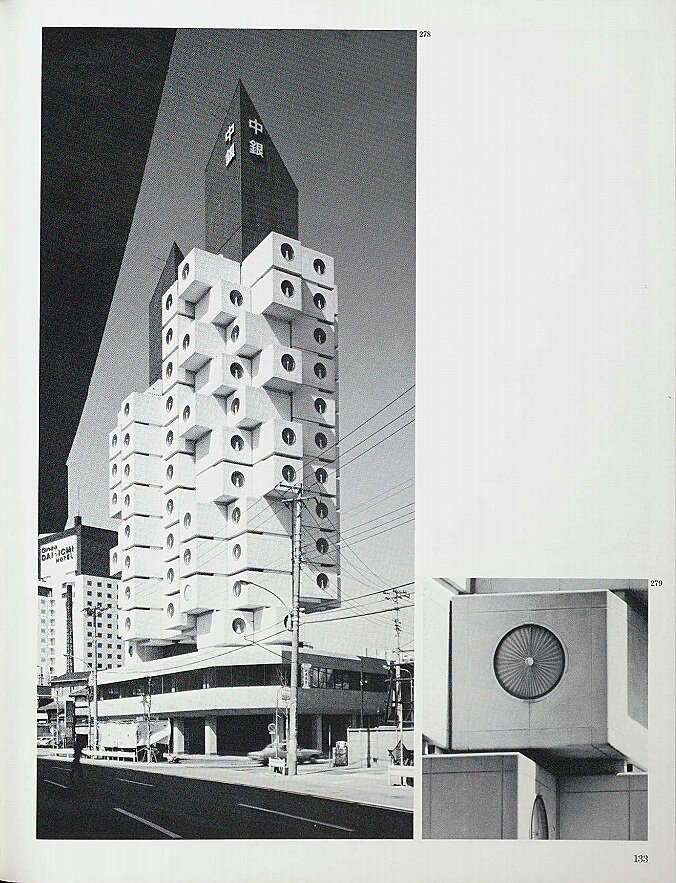

Burroughs Wellcome was recognized as landmark-worthy in a HABS report by the National Park Service. We fought, along with other organizations, to save the building & thousands of you signed a petition to stop the demolition. But what did Martine do? She sent her PR team to ask us to take down parts of our website that referred to the petition and demolition…

She cares about ‘green construction, including the world’s largest zero carbon building & laboratories, office buildings & residences.’ Zero carbon is not ‘green’ when you send 546,335 cubic feet of construction & 3,100 tons of steel to the dump to make way for your new project…

#Greenbuild invited her to give a keynote at tomorrow’s Global Health & Wellness Summit on Sept 9, 2021. According to https://informaconnect.com/greenbuild/summits/ the summit will ‘discuss how spaces are being redefined amid the ongoing climate crisis’ but does Martine’s solution make the problem worse in order to ‘fix’ it? The greenest building is the one that already exists…

PLEASE SHARE & IF YOU’RE GOING TO ATTEND ask WHY she tore down a Paul Rudolph landmark. Ask if the millions of $$ a year she makes as CEO of the company is the GREEN they mean in ‘Green Construction.’ More about the building is on our website (which Martine’s PR team doesn’t want you to see) at www.bit.ly/rudolphdemo

#PaulRudolph #greenbuild #greenbuilding #greenconstruction #RTP #architecture #brutalism #climate #wellbeing #UnitedTherapeutics @WELLcertified @USGBC @rickfedrizzi @docomomous @WorldGBC @ArchitectsJrnal @AIANational @archpaper @ArchRecord @usmodernist @preservationaction @bwfund @presnc @preservationdurham @c20society @brutalism_appreciation_society @sosbrutalism @ncarchitecture @savingplaces @modarchitecture

IMAGE CREDITS

NOTES:

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation gratefully thanks all the individuals and organizations whose images are used in this non-profit scholarly and educational project.

The credits are shown when known to us, and are to the best of our knowledge, but the origin and connected rights of many images (especially vintage photos and other vintage materials) are often difficult determine. In all cases the materials are used in-good faith, and in fair use, in our non-profit, scholarly, and educational efforts. If any use, credits, or rights need to be amended or changed, please let us know.

When/If Wikimedia Commons links are provided, they are linked to the information page for that particular image. Information about the rights for the use of each of those images, as well as technical information on the images, can be found on those individual pages.

CREDITS:

Photograph of Martine Rothblatt: Andre Chung, via Wikimedia Commons; Photograph of the Burroughs Wellcome building, in the process of demolition: detail of a photograph by news photojournalist Robert Willett, as they appeared in a January 12, 2021 on-line article in the Raleigh, NC based newspaper The News & Observer; Logo of the Global Health & Wellness Summit: from the web page devoted to the event.