FROM AN EXAMPLE OF CORPORATE PRIDE AND CUTTING EDGE RESEARCH—

—TO DEMOLITION BY NEGLECT AND MISINFORMATION.

The Burroughs Wellcome Building is no more.

One of America’s most forward-looking buildings, an icon of design, and -

the site of Nobel Prize-winning and life-saving research, and -

a research center designed for growth - a feature so appreciated by the client that they brought the architect back (three times!) to expand the building, and -

a building made, inside and out, to inspire and foster innovation, and -

a design so striking that it was used as sets for film and television, and -

a landmark of its region and state, and -

one of architect Paul Rudolph’s largest creations -

Modern architecture is part of America’s cultural legacy - and buildings designed by Paul Rudolph are among some of the best examples of the our architectural achievements: Rudolph’s architecture simultaneously displays practical innovation, creative exuberance, spatial richness, and symbolic depth.

Built as Burroughs Wellcome’s US headquarters and research center (and a prominent landmark within North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park), the building was praised by the company leadership which commissioned it:

“This building is an exciting and ingenious combination of forms [in which] one discovers new and different qualities of forms and spaces . . . a splendid climate for scientific scholarship and for the exchange of ideas.” — Fred A. Coe Jr., President of Burroughs Wellcome

and was hailed by:

and—most meaningfully, by the people who worked there:

“. . . .all of us who recall the vibrancy of this building . . . .I count myself very fortunate to have worked there. It was an amazing structure. We were young, and life was full of hope and promise. We were all witnesses, if not direct contributors, to amazing scientific discoveries and their promotion, during an exciting time for medical research.”

“I spent 32 years with [Burroughs Wellcome]. . . At that time, if any space was conceived to bring out the creative, inspirational, thoughts—this was it, in my opinion. I loved working there. We invented and developed more pharmaceutical products in those years. . . .We were “family” but more to the point we were colleagues who were allowed to trust the expertise of each other.”

United Therapeutics - the current owner of the site - had asserted that a significant portion of the building would be restored and reused, but - despite Burroughs Wellcome’s important history and innovative design - they decided to demolish the structure without discussion. So little discussion, that local preservation groups we reached out to about the demolition permit thought it must be for an anticipated asbestos abatement. Wholesale demolition was not considered a possibility.

When supporters learned of its impending demolition, there was enough people trying to see it that security had to push an existing fence farther from it to hide the destruction from the public. People we spoke to who tried to photograph the building were threatened by security guards with trespassing and had photos deleted from their cameras.

PROTECTING THE FUTURE OF THE PAST

Burroughs Wellcome, a significant work of architecture, is now permanently, irretrievably lost. This puts a spotlight on the need to protect America’s cultural heritage—and that includes this country’s great buildings.

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation and other organizations are engaged in that fight to preserve our past.

The destruction of Burroughs Wellcome led the United States chapter of the international preservation organization Docomomo to create The Advocacy Fund:

As part of our #ModernLove campaign, and in response to the recent demolition of Burroughs Wellcome, Docomomo US is announcing the creation of a new initiative: The Advocacy Fund. Gifts to this new initiative will go directly to critical advocacy efforts and will support local and national work.

Modern Love means many things to us: it means celebrating iconic sites like the Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice that received a 2020 Modernism in America Award of Excellence; it means fighting for significant sites like the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden; and it means avoiding the loss of significant buildings like Burroughs Wellcome designed by Paul Rudolph that was demolished earlier this year because it lacked appropriate preservation protections.

With your support, Docomomo US can provide assistance to local advocates and campaigns, participate in local and national preservation review meetings including the Section 106 process, and continue to speak out on the issues that concern you the most.

If the loss of the Burroughs Wellcome building makes you angry, please consider donating to the Advocacy Fund. All gifts up to $10,000 will be matched by the Docomomo US Board of Directors!

Buildings by Rudolph—among the world’s most significant works of Modern architecture—are continually threatened with demolition or abuse. Vigilance and advocacy is needed.

We are committed to urging, advising, and campaigning for the preservation (and proper care) of PAUL RUDOLPH’s architectural legacy.

Please give to the Advocacy Fund to preserve the richness of Paul Rudolph’s contributions—and to show:

Demolition is never the answer.

FROM AN ICON OF AMERICAN DESIGN —

— TO DEMOLITION DEBRIS.

And if you see something going on at a Rudolph site—that a building may be threatened, or is not maintained, or is about to be marred by an insensitive ‘update’ - please let us know (we’re easy to contact.)

IMAGE CREDITS:

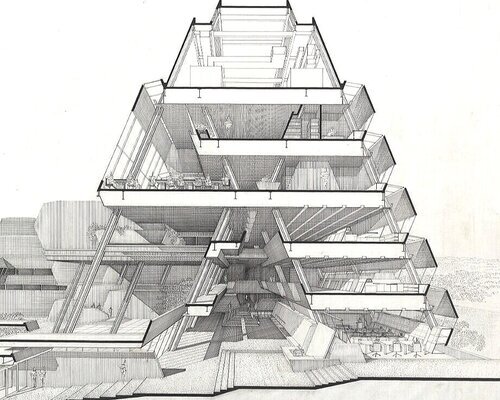

Top photograph of the Burroughs Wellcome Building: image courtesy of the Joseph W. Molitor architectural photographs collection, located in Columbia University, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Department of Drawings & Archives; Photographs of the Burroughs Wellcome building, in the process of demolition: photography by news photojournalist Robert Willett, as they appeared in a January 12, 2021 on-line article in the Raleigh, NC based newspaper The News & Observer; Perspective-section drawing, by Paul Rudolph, through the main body of the Burroughs Wellcome building: © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation