COMPARING ARCHITECTS: DIFFICULT AND DANGEROUS

Trying to compare architects (or more precisely: comparing their bodies of work) is a dangerous game—for the challenge immediately brings up a number of thorny, imponderable questions:

Balancing the factors to be judged, as listed at left, is part of the challenge.

Where would one begin?

What exactly is one comparing? [Technical mastery? Efficient planning? Aesthetic delight? Spatial variation? Contextual sensitivity? How much they changed the direction of architectural history? Diversity of building types? Energy efficiency? The satisfaction of their clients?. . . ]

If one is looking for an assessment of overall excellence, judging on a multi-factorial basis (including the above items), how does one balance and weight the factors?

For each factor, hat would one measure?

On what scale would one measure?

Is the notion of “measurement” meaningful in this domain?

Who are to be the judges?'

What values do the judges (the ones doing the comparing) bring to their decision-making?

All of these questions become ever more fraught in the context of our present culture, one whose behavior vibrates between two modes: pluralist, permissive non-judgementalism -vs- abrupt severity when making judgements. In architectural matters, we often feel sure of the rightness of our assessments (even the ones offered off-the-cuff) —yet we can crumble if ever asked to seriously and patiently address the questions of Who are we to judge? and Where do our standards originally derive from?

THE UNAVOIDABLITY OF JUDGEMENT

Philip Johnson: “We cannot Not know history” —a point which Johnson and Rudolph could both agree upon (but these long-time friends each used that lesson in very different ways.)

Paul Rudolph’s friend, Philip Johnson once scandalized the Modern architecture community by asserting:

“WE CANNOT NOT KNOW HISTORY.”

When offered, at mid-century, it seemed an outrageous claim. At that time many architects believed that (with the advent of Modernism) architecture had left history behind as something irrelevant to current practice.

[By-the-way: Johnson’s claim is one which we believe Rudolph would have agreed with—though with his own, very different ideas about what to do with such historical knowledge.]

Just as Johnson is reminding us that history is something that an honest and cultured architect cannot pretend to ever transcend, we also cannot pretend that we are exempt from making judgements—however difficult it is to try to make them.

Not only is it in our nature to offer judgement, but we are constantly called upon to do so in numerous domains and occasions, as when we are selecting collaborators, teaching, assessing what’s worth preserving, participating in juries, and prioritizing what to focus upon when working on a design (including where to allocate the budget). Most consequent of all judgements is when a client, about to enter upon a building project, makes the judgement about which architect to select for the commission. So we can make a parallel assertion to Johnson’s:

WE CANNNOT NOT MAKE JUDGEMENTS

—and, since in our education, work, and personal development, we model ourselves after the designers we admire, that inevitability of judgement applies to architects: we’ll never stop comparing them.

MAKING THE TASK A LITTLE LESS IMPOSSIBLE

Even though we’ll never stop trying to compare architects (judging their relative worth), we’ll never arrive at a broadly agreed-upon method for making “final and ultimate” assessments—and that’s owing to the fact that the scales-of-value shift in each era, as does the culture’s changing mood about what it finds interesting or crucial.

So the task is impossible—and even if it wasn’t impossible, it would be overwhelming because there are too many factors to consider. The good news is that the path is sometimes made a bit smoother for us by researchers who focus-in on a single aspect of architecture. By doing so—by showing how various architects have dealt with a specific issue—-these writers bring some clarity to the discussion. The seeming narrowness of their investigations calms the storm of mental overwhelm, and opens-up space for clearer thinking.

An excellent example is the work done by Kevin Bone and his associates, shown in the book “Lessons from Modernism,” which looked at the various ways that Modern architects—Wright, Aalto, Bo Bardi, Niemeyer, , Rudolph, and others—dealt with environmental issues, especially how they handled solar loads.

Lessons from Modernism, edited by architect and educator Kevin Bone, focused on strategies several prominent architects used when dealing with environmental concerns—especially solar loading. Two of Rudolph’s houses are analyzed in the book, and his Walker House is shown above.

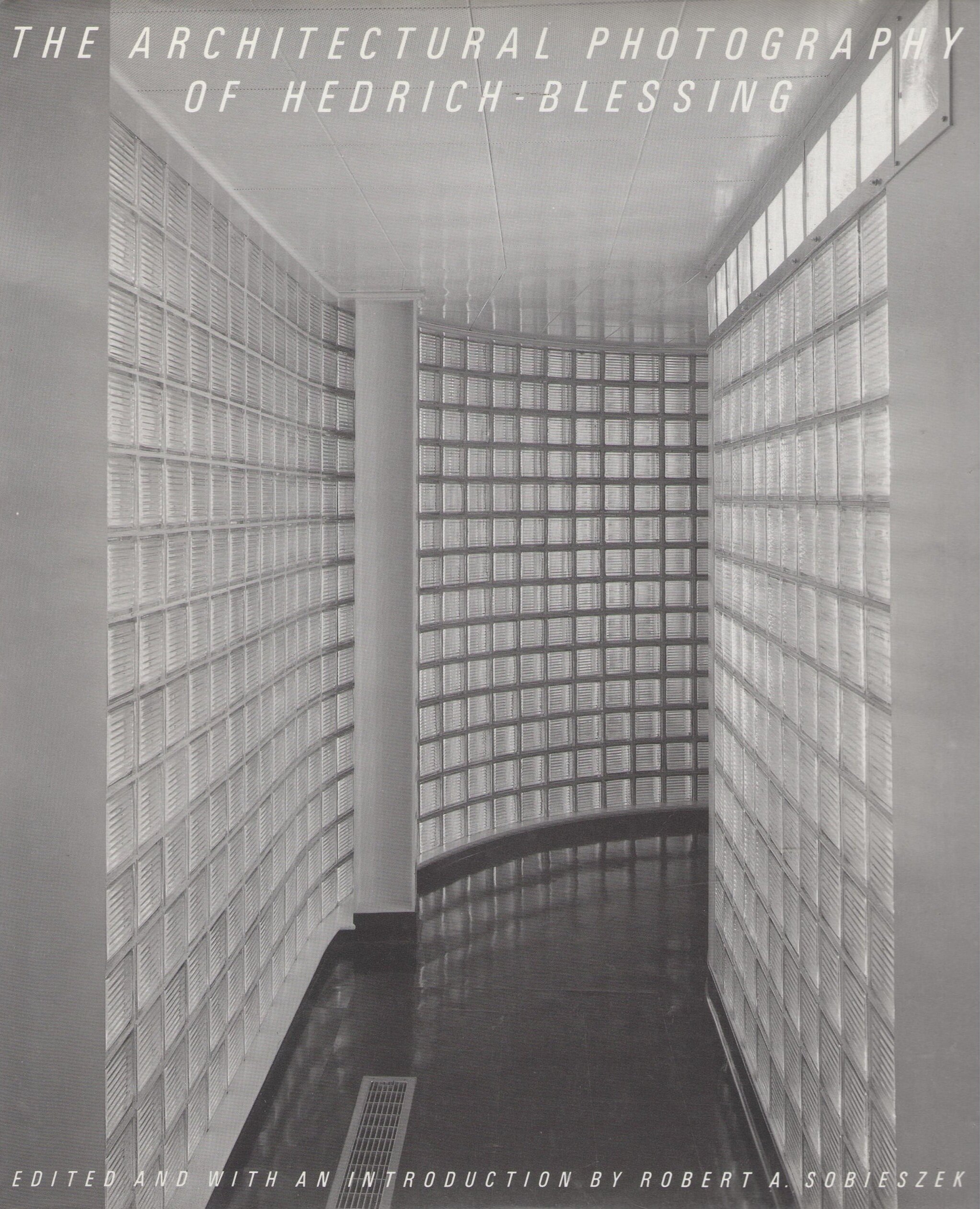

Another example of this type of highly focused study are books which highlight the use of a particular architectural material (i.e.: glass, concrete, ceramics, metalwork…) and show a banquet of photos and drawings of how various architects used and detailed them. “Design With Glass” and the two-volume “Aluminum in Modern Architecture” (see image at right), both by architectural writer John Peter, are classic examples of such books from the “mid-century Modern” period—and the one he wrote about glass included Paul Rudolph’s Jewett Arts Center at Wellesley College.

COMPARING ARCHITECT’S PLANS

Hideaki Haraguchi’s book— A COMPARITIVE ANALYISIS OF 20TH-CENTURY HOUSES — is in this tradition of studies which concentrate on one aspect of architectural creation. The author focuses-in on floor plans designed by the most prominent and creative architects of the Modern period—and he shares his research and conclusions in three illuminating ways:

Chapter essays (“Tripartite Composition”, “The English Tradition”, “Towards Universal Space”…) about the various families of approaches used in the the design of house plans—richly illustrated with many examples from each era

An extensive timeline, from the 1400’s to the 1980’s, showing transformations in the design of residential plans—with examples of representative plans inserted within the chart

Numerous illustrations of the houses, based of the plans: over 100 axonometric drawings

Paul Rudolph’s work is cited in the chapter in which the author analyzes how Mid-century designers began to depart from the use of the “Universal Space” concept for residential planning (an approach which had previously been favored among Modern architects.)

The book includes a fold-out timeline to show the evolution in Modern architects’ approaches to residential planning. Rather than just name the architects (or the houses), the author places small images of the each of the plans on the chart—a graphically helpful method.

GRAPHIC AND SPATIAL ANALYSIS

The author’s depiction of two levels of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robie House—one of the numerous drawings in the book which use the axonometric drawing technique to convey spatial quality as well as the plan layout.

The author, via those 3 ways of telling the story of the changes in house design, offers rich insights into master architects’ planning philosophies, techniques, and styles—and the historical context in which they operated.

But the real glory of this study are the abundance of drawings which the Haraguchi created for the book. These drawings show the plans, but also convey a sense of the each house’s spaces by also showing the walls, columns, and window & door openings—and the author does this in through axonometric drawings.

That’s a type of drawing where it looks like the walls are being extruded upward from the plan—so it an axonometric drawing not only shows the layout of the rooms, but also tangibly suggests the type of spaces which the layout gives rise to. [Although Paul Rudolph was known as a master of perspective drawing, he sometimes also utilized the axonometric drawing technique—and we posted an article about that here.]

In addition to using this explanatory drawing technique, Haraguchi’s drawings are reproduced as white images on a black background. This not only evokes the authority of traditional architectural blueprints, but this graphic approach also adds a sense of visual drama which focuses the reader’s attention.

RUDOLPH, IN WHITE ON BLACK

Those drawings are the real treasures of this book. Using that technique, Haraguchi drew over 100 axonometric plans of house designs, by forty-five 20th Century architectural masters, including:

Wright, Hoffmann, Lutyens, Niemeyer, Taut, Sharoun, Le Corbusier, Rietveld, van Doesburg, Chareau, Mies, Breuer, Neutra, Kahn, Venturi, Eisenman, Tigerman, Botta, Rossi—and Rudolph!

Paul Rudolph is represented by houses designed across a quarter-century of his prolific career—from the 1948 Siegrist Residence -to- the 1972 Micheels Residence. The author gives emphasis to one of Rudolph’s finest designs: the Milam Residence of 1959, showing both levels of the house.

The two-page spread wherein Haraguchi explores—via axonometric drawings—three of Rudolph’s house designs. LEFT-HAND PAGE: the 1959 Milam Residence (showing both levels.) RIGHT-HAND PAGE: the 1972 Micheels Residence (shown lower-left), and the 1948 Siegrist Residence (shown upper-right.)

A closer view of the page with the Haraguchi’s drawings of Rudolph’s Milam Residence in Ponte Verda Beach, Florida. It shows the house’s two levels, and the use of axonometric drawings convey information not only abut the layout of the rooms, but also about how the walls, windows balconies (and double-height planning) shape the interior spaces.

THE POWER OF COMPARISONS

Brian Sewell was one of Britain’s most perceptive art critics (and one of the most controversial.) In this powerful video segment, about developing one’s aesthetic sense, he cites the effective use of comparison.

Comparison can be a powerful tool—especially when a scholar provides opens up the question by providing materials which allow us to intensely focus-in on an aspect of architectural design.

Brian Sewell (1931-2015), the British art critic known for his fiery opinions, as well as the depth and sensitivity of his knowledge, spoke inspiringly about the importance of comparison—what he called “a repeat experience”—for developing a deeper sense of what’s significant and beautiful. He was speaking of painting and sculpture—and the same approach can be applied to the art of architecture.

For gaining an in-depth knowledge of the approaches that were used in designing the Modern masterworks of residential architecture—how such strategies evolved, varied, an reflected larger issues and philosophies in the architecture of that century—Hideaki Haraguchi’s A Comparative Analysis of 20th-Century Houses is an indispensable resource, guide and well of insight. That he included several examples of Paul Rudolph’s work is additional evidence of the author’s wisdom.

Returning to our original theme—the difficulty of comparing architects—and the multiple obstacles entailed in such a task: this book’s concentrated examination of a single aspect of architects’ work is the sort of study that can aid—via its focus and profound clarity—in making such challenging assessments.

BOOK INFORMATION AND AVAILABILITY:

TITLE: A Comparative Analysis of 20th-Century Houses

AUTHOR: Hideaki Haraguchi

PUBLISHER: In Great Britain: Academy Editions; In the US: Rizzoli International

FORMAT: Paperback, 11-1/2” x 11-1/2”, 92 pages, hundreds of illustrations

YEAR OF PUBLICATION: Great Britain: 1988; US: 1989

ISBN: 0-8478-1023-2

AMAZON PAGE: here

ABEBOOKS PAGE: here

A broader view of the timeline in Haraguchi’s book, in which the author traces the evolution of architects’ residential planning over the course of the several centuries. Plans, representative of changing philosophies of design, are inserted into the chart—aiding the clarity of the presentation.

IMAGE CREDITS:

Balance scale: photo by Poussin jean, via Wikimedia Commons; Photo portrait of Philip Johnson: photograph by Carl Van Vechten, from the Van Vechten Collection at the Library of Congress