Paul Rudolph’s design for a Manhattan mega-structure makes an appearance in this new film…

Paul Rudolph's Futuristic Vision: The Galaxon

Rendering of Paul Rudolph’s ‘Galaxon’. Image: Shimahara Illustration

VISIONS OF THE FUTURE

There are not many phrases more evocative than “THE FUTURE”. Whether in joyous expectation or fear (of a mixture of both), imagining, predicting, envisioning, and forecasting The Future has been one of humanity’s longest obsessions - and indeed, many religious and social practices, going back to the most ancient of times, are concerned with prognostication.

New York World’s Fair Button from the General Motors Futurama Exhibit. Image: www.tedhake.com

But, beyond the products of imagination (literature, art, and film), where can one actually go to get a tangible touch, a taste of the future? Not a virtual reality version, but rather an experience where one can actually wander around samples of a futurific world? The answer is—or rather, was—world’s fairs.

WORLD’S FAIRS — THE GEOGRAPHY OF WONDER

Humans also have a taste for novelty, adventure, the exotic, and news from beyond our borders (and products, material and cultural.) One phenomenon brings such appetites together with our fascination with the future: World’s Fairs.

World’s fairs were international events, taking place in intervals varying from several years to several decades. A city—like Paris, London, Osaka, New York, Seville, Rome - would be selected, and countries, states, companies, and trade organizations (and even religions) would erect pavilions - each of which would show the sponsor’s self-image and aspirations to the fair’s visitors (coming, often from all-over-the-world, during the fair’s few months duration.)

For countries, their industrial, consumer, and agricultural products would be featured, along with something of the nation’s culture—and generally there would be a lauding of the leaders, government, and “way of life”.

Companies, too, would extol their accomplishments, productive might, and the quality of their products. Most interestingly, they would often present displays about the forefront - The Future - of technology in their field. Sometimes such demonstrations were startlingly dramatic, but sometimes amusingly humanizing—like the talking (and joking) robot, Elektro (with his robot dog, Sparko), who were featured in the Westinghouse pavilion of the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair.

The architecture of the pavilions in world’s fairs have been particularly powerful evokers of “tomorrow.” Examples range from the jaw-droppingly giant (for that time) open space (377 feet x 1378 feet, and open to a height of 13 storeys) of the Galerie des machines in the 1889 Paris fair to the gargantuan geodesic dome of the US pavilion in Montreal’s Expo 67. Each building competed for the visitor’s attention—and, through striking shapes, unusual construction systems, and the manipulation of light (natural and artificial), often created dream-like, fantasy, forward-looking/futuristic icons. Sometimes a whole landscape would be populated by these odd, wonderful, future-dreamy buildings—like this view from Expo 67:

Photo: Laurent Bélanger from wikipedia

One of the most famous pavilions of the 1939-1940 New Fair was the “Futurama” exhibit created by Norman Bel Geddes for General Motors: using architecture, and giant, detailed, moving, and carefully lit models, it showed kinetic, luminous visions of tomorrow, beguiling visitors with an image of a motorized utopia. Upon leaving, attendees were given a button that read “I Have Seen The Future”—and no they doubt felt they had.

Even at the distance of decades, the images created by Bel Geddes and his team—and the future-oriented displays and architecture of the fair’s other pavilions—continue to fascinate, and evoke that “If only…” feeling. The great author William Gibson wrote of the ongoing seductiveness of such visions in his short story, “The Gernsback Continuum.”

NEW YORK AND THE FUTURE—AGAIN!

The New York World’s Fair, spoken of above - considered to be one of the greatest fairs of all - took place in 1939 and 1940, just before World War Two. But well after that war - in the midst of the 60’s, one of the USA’s most economically & militarily strong (and socially vibrant) periods - a second world’s fair was held in New York City.

Photo: Anthony Conti; scanned and published by PLCjr

That fair—the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair—was planned on the same pattern as the previous one: countries, companies, and groups each showing themselves off—only this time, with updated images of the future. For better-or-worse, the world had moved from planes to jets, from vacuum tubes to transistors, and from hydro to atomic power. The Future had new horizons—and that future was: Outer Space.

EVERY FAIR NEEDS A SYMBOL

Almost all world’s fairs have had a central building or structure—that serves to symbolize the fair. It is used both to distill the message of the fair, as well as to create an icon around which communication and marketing can be done (as well as being suitable for souvenirs!)

For the 1939 New York World’s Fair, that symbol had been the Trylon and Perisphere: these were huge platonic forms - a gigantic sphere and a spiky, towering, elongated tetrahedron (designed by Harrison and Fouilhoux). They were large enough for visitors to enter, and there was an exhibit inside about the city of the future (designed by Henry Dreyfuss).

Trylon & Perisphere Monuments of 1939 World's Fair in Flushing Meadows Linen Postcard. Photo: Michael Perlman

But for New York’s 1964-1965 fair, a new symbol would be needed. Here’s what Robert Moses - the fair’s boss - said about the search for a symbolic structure:

“We looked high and low for a challenging symbol for the New York World's Fair of 1964 and 1965. It had to be of the space age; it had to reflect the interdependence of man on the planet Earth, and it had to emphasize man's achievements and aspirations. … and built to remain as a permanent feature of the park, reminding succeeding generations of a pageant of surpassing interest and significance.”

A LOFTY VISION - IN CONCRETE

Concrete may be hard and heavy—but it can be manipulated make soaring structures of deft grace and even visual nimbleness. Nor does the concrete industry want to be thought of as stodgy, as they are always showing that they are moving ahead with forward-looking research and engineering—indeed, the American Concrete Institute once produced a set of research findings and projections on the possibility of using their material in a non-terrestrial environment, a book called “Lunar Concrete”!

The Portland Cement Association is, since 1916 “ the premier policy, research, education, and market intelligence organization serving America’s cement manufacturers. … PCA promotes safety, sustainability, and innovation in all aspects of construction, fosters continuous improvement in cement manufacturing and distribution, and generally promotes economic growth and sound infrastructure investment.”

Like other trade associations and companies, the Portland Cement Association wanted to be represented at the fair—and in a very forward-looking way. So they put forward a design for the fair’s central, symbolic structure—one that would embody a feeling of future-oriented optimism (and, of course, use portland cement!)—and they hired Paul Rudolph to design it.

THE GALAXON

Paul Rudolph came up with one of his most daring designs—and, given that Rudolph was one of the world’s most adventurous architects, that’s saying a lot.

His design was christened “The Galaxon”, and Architectural Record magazine reported:

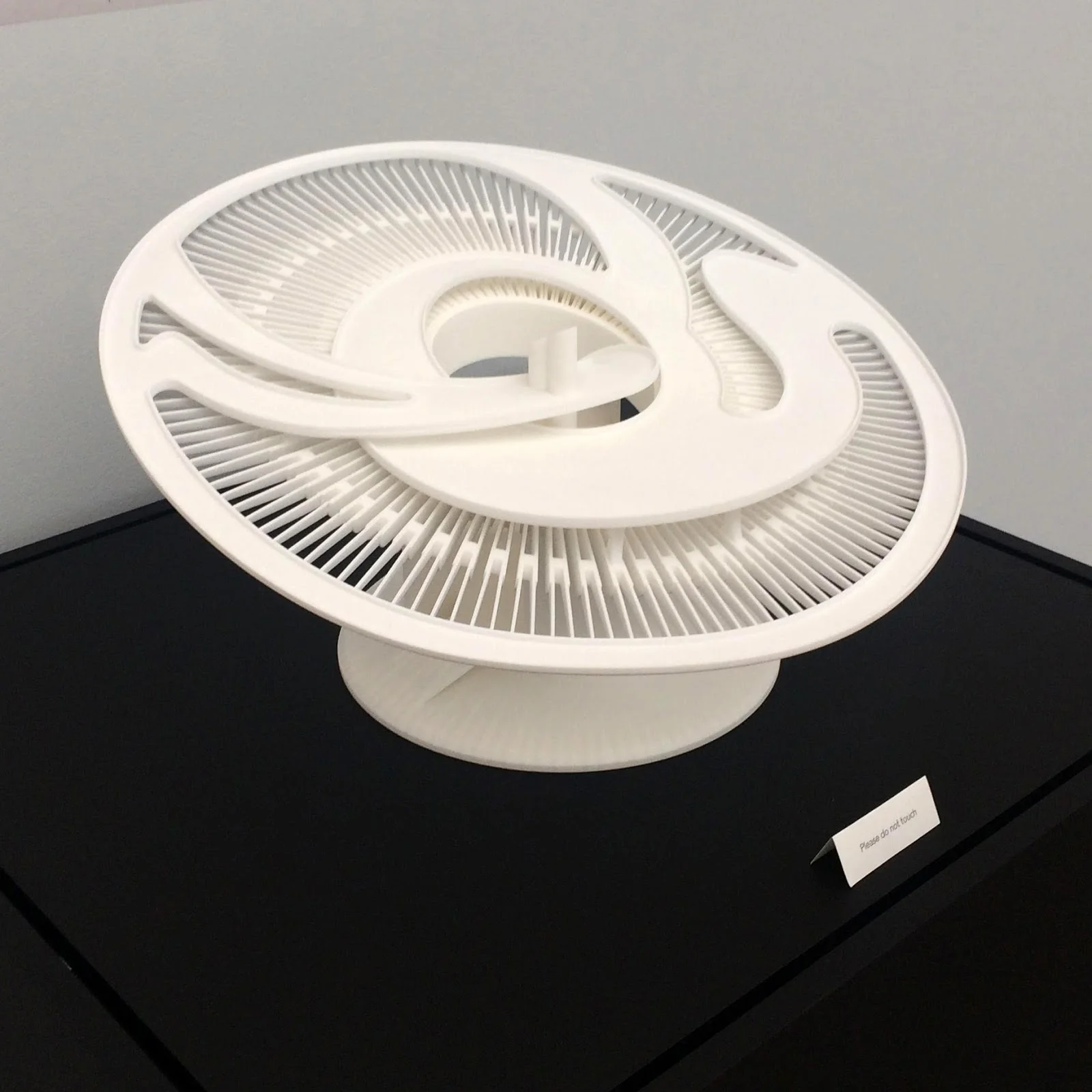

“The Galaxon, a concrete ‘space park’ designed by Paul Rudolph, head of the Department of Architecture at Yale University, has been announced by the Portland Cement Association as ‘a proposed project’ for the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Its cost is estimated at $4 million.

Commissioned by the P.C.A. as ‘a dramatic and imaginative design in concrete,’ the Galaxon consists of a giant, saucer-shaped platform tilted at an 18-degree angle to the earth and held high above it by two curved walls rising from a circular lagoon. The gleaming 300-foot diameter disc of reinforced concrete would hover in the air like some huge space ship. Visitors would be lifted to the center of the ‘saucer’ by escalators and elevators inside the curved supporting walls. From the central ring they would walk outward over curved ramps to a constantly moving sidewalk on the disc’s outside perimeter. The sidewalk would rise and fall from the 160-foot high apex of the inclined disc, to a low point approximately 70-feet above the ground.

A stage is projected from one of its two supporting walls and a restaurant, planetary viewing station and other educational or recreational features could be located at points along its top surface to make it an entertainment center. The Galaxon was among several designs displayed at an exhibition in New York of the use of concrete in so-called ‘visionary’ architecture.”

- Architectural Record, July 1961

Rudolph did not disappoint—and he created drawings and a model to convey his striking design. The drawings themselves are impressive, with the main one stretching to nearly 20 feet long.

Photo of Rudolph’s presentation model. Image: http://www.nywf64.com

Drawing of night view (with spotlights). Image: "Remembering the Future," "Something for Everyone: Robert Moses and the Fair" by Marc H. Miller, published to accompany the 1989 Queens Museum exhibition "Remembering the Future: The New York World's Fair from 1939 to 1964."

A VISION SPURNED

The real power (to select the central, symbolic structure) rested with Moses - the famous (or, to some, infamous) Robert Moses, who’d built so many bridges, roads, and other facilities, all over the tri-state area. Of searching for an iconic central structure for the fair, he said:

“We were deluged with theme symbols - mostly abstract, aspirational, spiral, uplifting, flashing, or burning with a hard and gemlike flame, whose resemblance to anything living or dead was purely coincidental.”

Among the several many designs that Moses rejected was the Galaxon.

And so another structure was chosen, the Unisphere (made from a rather different material: stainless steel - and sponsored by a major manufacturer: US Steel). The Unisphere—still in place after all these years—admittedly has some uplifting visual power, and does still speak to the goal of a unified world.

But it’s not the forward-looking, FUTURE-evoking, space-expansive, upward-aspiring GALAXON.

Fortunately, we have Rudolph’s beautifully drawn visions to sustain our dreams.

PUBLICATIONS, ARCHIVE, AND EXHIBITION

When the Galaxon was originally proposed, it got some press—and it has since also appeared or been mentioned in books on Rudolph, and been on-exhibit.

Paul Rudolph was known for his virtuoso presentation drawings (especially perspectives and sections), and Paul Rudolph: Drawings is a beautiful, large book of them. It was edited by Yukio Futagawa, and published by A.D.A Edita Tokyo Co., Ltd. In 1972. The book includes a well-reproduced perspective view and a section of the Galaxon.

The preponderance of Paul Rudolph’s architectural drawings (well over 300,000 documents!) are in the Library of Congress. The collection includes several fascinating drawings of the Galaxon, which have been scanned and can be seen on-line.

Paul Rudolph’s original rendering. Image: Library of Congress

From the Library of Congress, impressively large, full-size reproductions of Paul Rudolph’s Galaxon drawing were made, which were very prominently displayed in the exhibit, Never Built New York (which was on-view at the Queens Museum from 2017-2018.) While the Galaxon didn’t make it into the exhibit’s catalog (the curators discovered it after the book had gone to press), the catalog is still well worth obtaining, as it is an exceptionally rich collection of visionary proposals for New York City - and it does include other fascinating projects designed by Paul Rudolph.

Rudolph's LOMEX project featured in new Renderings

View from a terrace in the high-rises. Image: Lasse Lyhne-Hansen

Paul Rudolph’s Lower Manhattan Expressway project (LOMEX) has been digitally recreated by Danish designer Lasse Lyhne-Hansen. As featured on design websites Archdaily and Designboom, the work was created to celebrate Paul Rudolph’s 100th birthday.

Rudolph’s proposal for the Lower Manhattan Expressway. Image: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Robert Moses originally conceived of the Lower Manhattan Expressway project in 1941 and given the authorization to proceed in 1960. After numerous protests, including notable figures such as Jane Jacobs, the project which was to be an elevated highway was replaced by a sunken highway with adjacent parks and housing.

Then, writes Phil Patton in the Architects Newspaper:

In 1967 the Ford Foundation, whose new head was McGeorge Bundy (formerly National Security Advisor during escalation in Vietnam), asked Rudolph—known for large-scale projects—to imagine a development that ameliorated the impact of the highway. He proposed topping the sunken freeway with a series of residential structures, parking, and plazas, with people-mover pods and elevators to subways. The shapes of the buildings echoed the Williamsburg and Manhattan bridges, and also recalled Hugh Ferriss’ ideas of bridge/buildings from 1929. Rudolph’s idea was organizing a new city core around modes of movement.

“This plan, unlike most, does not propose to tear down everything in sight; it suggests that we tear down as little as possible,” Rudolph said about the project at the time.

Rather than challenging the need for a massive highway that would have destroyed most of SoHo and Tribecca, Rudolph believed architecture could make the most of the given situation.

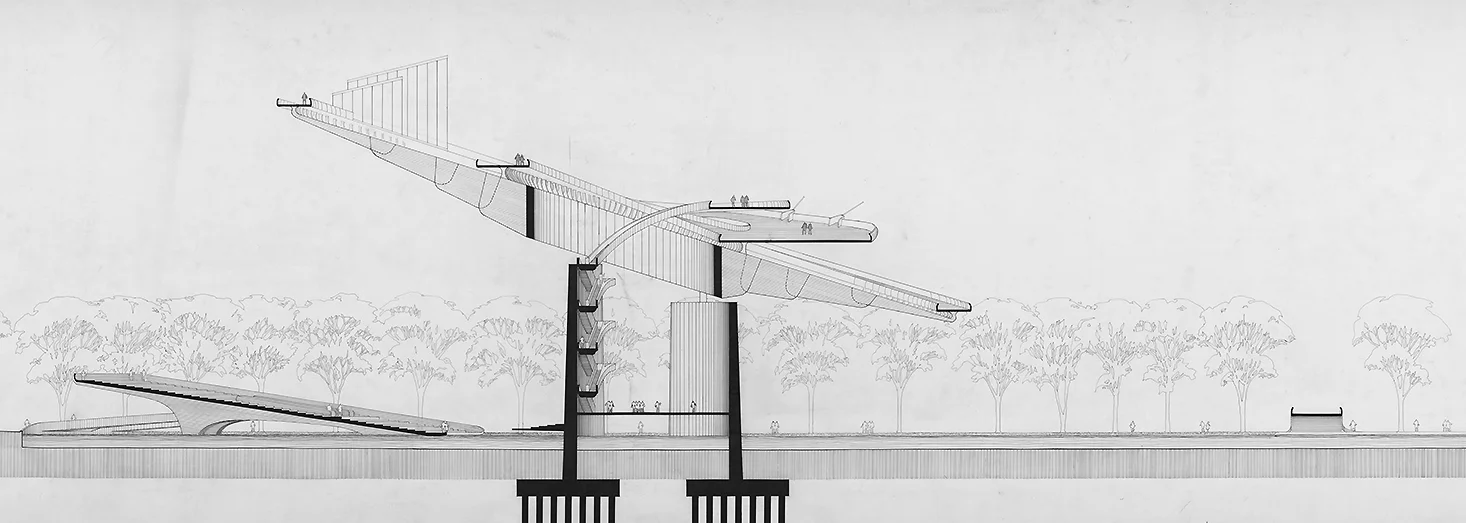

Rudolph’s original section perspective. Image: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

In 1971, the project was ended by Governor Nelson Rockefeller.

Decades later, a similar scale project - the 'Big Dig' in Boston - would install the 1.5 mile-long Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway series of parks and public spaces above its new underground highways.

To see more renderings of what might have become of New York, click the links below: