We are grateful to the AIA Florida, and especially to their Chief Operating officer, Becky Magdaleno, for permission to reproduce the full text of this interview—which we present here.

[Note: we have maintained the spelling, grammar, and punctuation, as it originally appeared in the article.]

FLORIDA ARCHITECT Interviews: Paul Rudolph

"The built environment is too important to leave to architects.”

October 10, 1982

Florida Architect: It's been a long time since you've been back to Florida after working here for so long. Were you surprised by the way the State has changed?

Rudolph: Well, it shouldn't be a surprise, but, of course, you do remember things in certain ways. The sheer volume of building, not just high rise, but everything, is very different and one has to be surprised.

FA: I'd like to talk a little about building scale. One of the firms which won a design award this year was Arquitectonica. Their Overseas Tower was described by the jurors as a good piece of highway architecture. This highway network of ours is a relatively new growth area with a very different scale from that found in the city. It's a scale that many of us are not used to working with and think in some ways it is not as enjoyable a scale as the one you were working with in Sarasota.

Rudolph: I wonder, when you make that statement, if you're not hiding under a bush. My thesis is that the population explosion isn't over yet. No one is going to give up his car or the public transportation system. The number of people living in our cities just hasn't reached its peak. There is no way, of course, that architects can determine such a thing. But, it does take architects to find solutions to the problems created by expanding cities and highway systems. In that way, society determines what architects do. Architects often think it's the other way around, but it isn't. So, with regard to your comment about the scale of the work in Sarasota being a more enjoyable scale than say, highway architecture, I don't agree. I don't think that bigness is bad or that small is beautiful,

FA: When you left Florida, was it because you saw what was going on around the rest of the country and you wanted to contribute to a new scale that was being tried?

Rudolph: No. The reason why I left Florida was extremely complicated and had nothing to do with that. I did then, and still do, want to work on very large projects. I think it's wrong, as is frequently done here, to deplore the fact that Siesta Key has lots of highrise buildings. The real question is what kind of highrise buildings and how are they placed in relationship to one another,

FA: I certainly agree with that. And the reality of the fact, here in Florida at least, is that everyone wants to be on the beach. If we're going to put all those people on the beach, then our buildings have to go up higher and higher. Single-family bungalows just can't do it anymore. But I repeat my earlier question which is 'do I really have to accept that this is the way society should be going?

Rudolph: I am giving the Walter Gropius lecture at Harvard next week and I am going to talk about essentially this very thing. I’m going to talk about urbanism, and my thesis about it has to do with a lack of understanding of scale. I think this is one of the dreadful things that architects have fallen into … thinking that it's big and therefore it's bad. I really don't agree with that.

FA: I agree that a large building can be very human and urbanism very exciting and that together they create something that nothing else can. I am wondering though, if that is what's happening here in Tampa for example.

Rudolph: The problem, in any city, is not whether the buildings are large or small. When you posed that question to me, you alluded to "a large building". What I am concerned about is groups of buildings, not single isolated structures. We build too many isolated structures which, whether big or small, sit all unto themselves. They are unrelated to the next building in any way. Since there is no real theory about how to interconnect these buildings, each remains isolated, a law unto itself. When I look at the great architecture of the past, I find that it wasn't that way at all. There was every much a professional assembly of buildings and I think that's what we need to get back to.

FA: In a lot of ways what we're talking about is planning. Do you agree?

Rudolph: Yes, but you can’t throw it all off on the planners, either. Just establishing a planning code or a set of rules doesn’t make an environment. What it takes is ideas and sensitivity and the lack of coordination within our cities is not exclusively the fault of the planners.

FA: I don't think would try to blame it on the planners, but I think in any city you need a good planning basis.

Rudolph: I see it this way. Say that a throughway is needed through the middle of a city. The project is essentially executed by transportation engineers. Frequently the project becomes a political hot potato concerning where the road can or cannot be put based on so-called "feasibility studies." All of this sort of thing takes its own toll and eventually the road takes it's own form. It may be well done or not so well done. But, what's left is for the people to react to the project and patch up whatever can be patched up. It’s a natural follow through. One of Michelangelo}s greatest buildings, the Campidoglio in Rome, is really a patch up—a remodeling. There were a lot of helter skelter medieval buildings all around and Michelangelo remodeled the Campidoglio into one of the world's great works of architecture. There is nothing wrong with that.

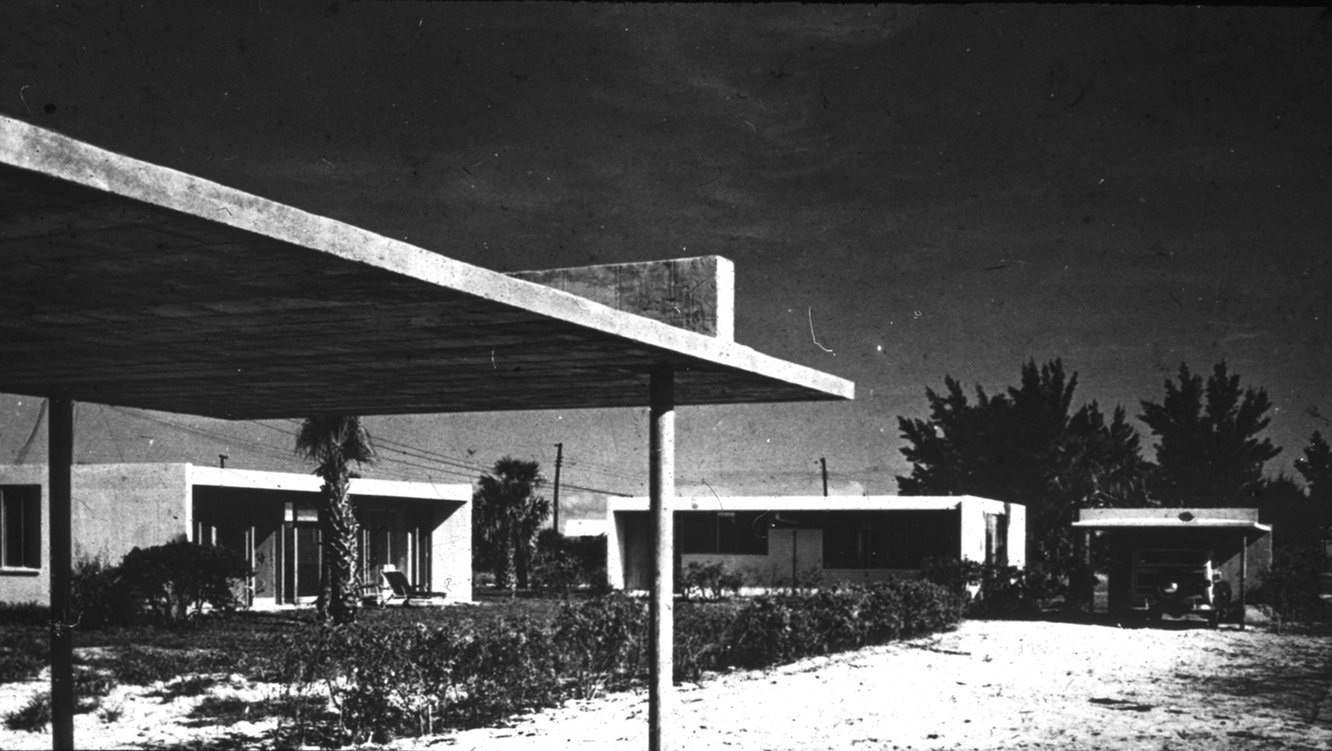

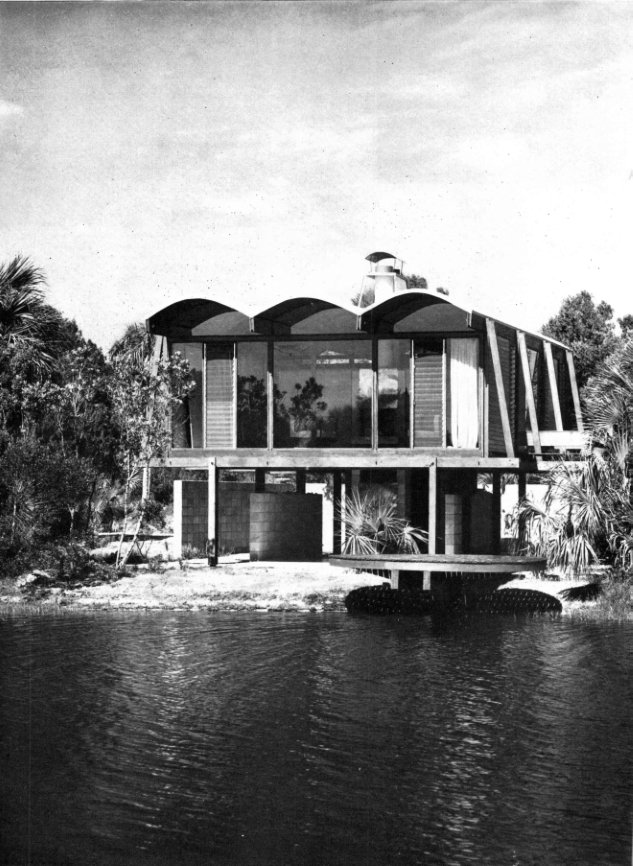

FA: There was a kind of purity of structure that is very obvious to me in the early work in Sarasota. Do you think that it is almost an exercise that architects have to go through where they are totally fascinated with structure, and then with space and then with scale?

Rudolph: The essence of architecture for me is the appropriate psychology of space. As a matter of fact, my definition of architecture is that it is used space modified to satisfy man's psychological needs. How you achieve that space can be done in a lot of different ways. And that, of course, has to do with structure. I don't want to say that structure isn't important, I am just saying that it is secondary to the impression the building creates. I do, however, agree with your statement to the extent that I think in the early days in Sarasota architects were more concerned with how to put things together, how to connect to a column and so forth.

FA: Recently a forum was held in Tampa on the status of the arts. A panel of a dozen people was assembled, not one of which was an architect. I think that sums up the way a lot of people feel about architecture, that it isn’t an art form at all, it's a function. Many people seem to feel that architecture is little more than frivolous space … expensive frivolous space. If architects are now being relegated to the position of being little more than builders, because of the economy or whatever, then what is the point of being an architect?

Rudolph: I don't agree with your assessment. Not at all. I think the built environment is too important to be left to the architects. History shows that vernacular buildings can rise to tremendous aesthetic heights. The medieval hill towns, the Ponte Vecchio, none of these had architects, and they were all great contributions to the environment. One problem is that architects don't understand their role in society and, admittedly, it’s complicated. I do have great faith in the people and I think that too many architects ignore what the people want and need from architecture. Architecture is a matter of imagination, intellect and will. I'm sad that we architects get confused by making great works of art rather than what the people need.

FA: My response to that is that I do believe that as a city develops, we architects have a wonderful opportunity to create great space and wonderful scale.

Rudolph: But, we have to find other ways of handling simple things like the space between the parked car and the entrance to the building. I feel very dismal that that sort of thing has been overlooked for too long and I sometimes feel that it would be better left to the engineers. The whole circulation system that is created in a city dictates the way people perceive their environment. If parking is a problem and it takes thirty minutes to get from the car to the building then that perception is not good. Kennedy Airport is a classic example. Here we have the gateway to this country and it is all out of scale and difficult to navigate. It's just unfortunate that for many people that is the first thing they see of this country.

FA: I'd like to ask you about building ornament. Do today’s architects know how to decorate their buildings?

Rudolph: There is something innate about people having a need to decorate. In my opinion, we really don't know how to decorate. And, again, that has to do with scale. Decoration, quite obviously, gives meaning to a building. All the great architects through history have used decoration, including Wright and Corbusier. I think that decoration is particularly important for public commemoration and that the people need to suggest what the ornament should be. Public ornament and public sculpture may be the solution to the very things that our cities need, i.e. a sense of scale and less isolation and loneliness of one building to another. Historically man has done much better with his cities and I don't know why we can't today.

Jan Abell is a principal in her own Architectural firm, Jan Abell Architects, Tampa, Florida and is currently involved in the organization of the Architecture Club of Tampa.

![An exterior side elevation of the terminal building. The capsule-like control tower [another saucer?—perhaps Rudolph saw Wright’s renderings?] is in the background at the right. The building’s columns appear to flare outward at their tops: a form re…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1563827539259-S0MVUHOMK3FBK8X4W0EP/Airport+side+elevation.jpg)