Dr. Walker, his children, and his children’s children, have lived in and loved the Walker Guest House—designed by Paul Rudolph.

Beloved Rudolph Design, The Walker Guest House, To Be Auctioned

Paul Rudolph and Circular Delight

Image: cargocollective.com

FAMILIAR FORMS

When one thinks of an architect, naturally one visualizes their most famous buildings - but, as much a part of that imaging process are the forms & shapes which you primarily associate with their work.

Thus, entrained with any thought of Wright, are the forms of his thrusting/cantilevered horizontal planes, counterpointed by solid masonry masses, his rhythmic verticals, and rigorous-but-playful use of circles. For Mies, it might be his floating, shifting planes (as in the Barcelona Pavilion), his cruciform column (from the same project), and his glazed grids. Corb is associated with a big vocabulary of forms—and strongly with his more sculptural shapes (like at Notre Dame du Haut) or, conversely, his platonically geometric “purism” (as in his Villa Stein or Villa Savoye).

A photo and plan-detail drawing of Mies van der Rohe’s “cruciform column”, as used in his 1929 Barcelona Pavilion. Image: www.eng-tips.com

CURVILINEAR CONCEPTIONS

When it comes to forms, there’s something inherently pleasurable in curves and circles—one wonders if we, unconsciously, relate it to the pleasures and vitality of human bodies - or life itself. And it’s useful to recall that the education of all artists (and architects) - at least ‘till recently - included figure drawing.

With Rudolph, one doesn’t often think of circles, but he was hardly allergic to using curves in his work. They show up, sometimes most effusively, several times in his oeuvre. An example would be one of his most famous designs: the Healy Guest House:

Paul Rudolph’s perspective rendering of the Healy Guest House (also known at the “Cocoon House”), with its suspended, catenary curve roof. It was built in Siesta Key, Florida. Image: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Or in this baroquely sensuous set of stairs:

A staircase in Paul Rudolph’s Government Service Center in Boston. Photo: NCSU Libraries

Or his intriguing proposal for the Inter-American Center:

Rudolph’s design for the bazaar-market building, part of the Inter-American Center (also known as the Interama) project, which was envisioned for the Miami area of Florida. Image: Library of Congress

There are other projects of his where flowing curves show up, but we’ll end with Rudolph’s own NYC apartment: its modest-size living room was enhanced by the floating curves of hanging bookshelves which surrounded the space:

Sinuously curved suspended shelving provided space for book storage and display, in Rudolph’s own NYC apartment. Photo: Tom Yee for House and Garden

CIRCLING BACK TO WRIGHT

But what about circles in Rudolph’s work?

For that, we need to return to Wright. The two great influences which are often cited for Rudolph are Wright and Le Corbusier. Wright - for his richly layered, deep-perspective spaces; and Corbusier - for the bold, sculptural plasticity of (especially) his later works. With Wright, we know the connection is not spurious, for we have a photograph of the youthful Rudolph visiting a Wright-designed home:

Rudolph (at left) and family members, visiting Wright’s Rosenbaum House in Alabama.

Photo: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

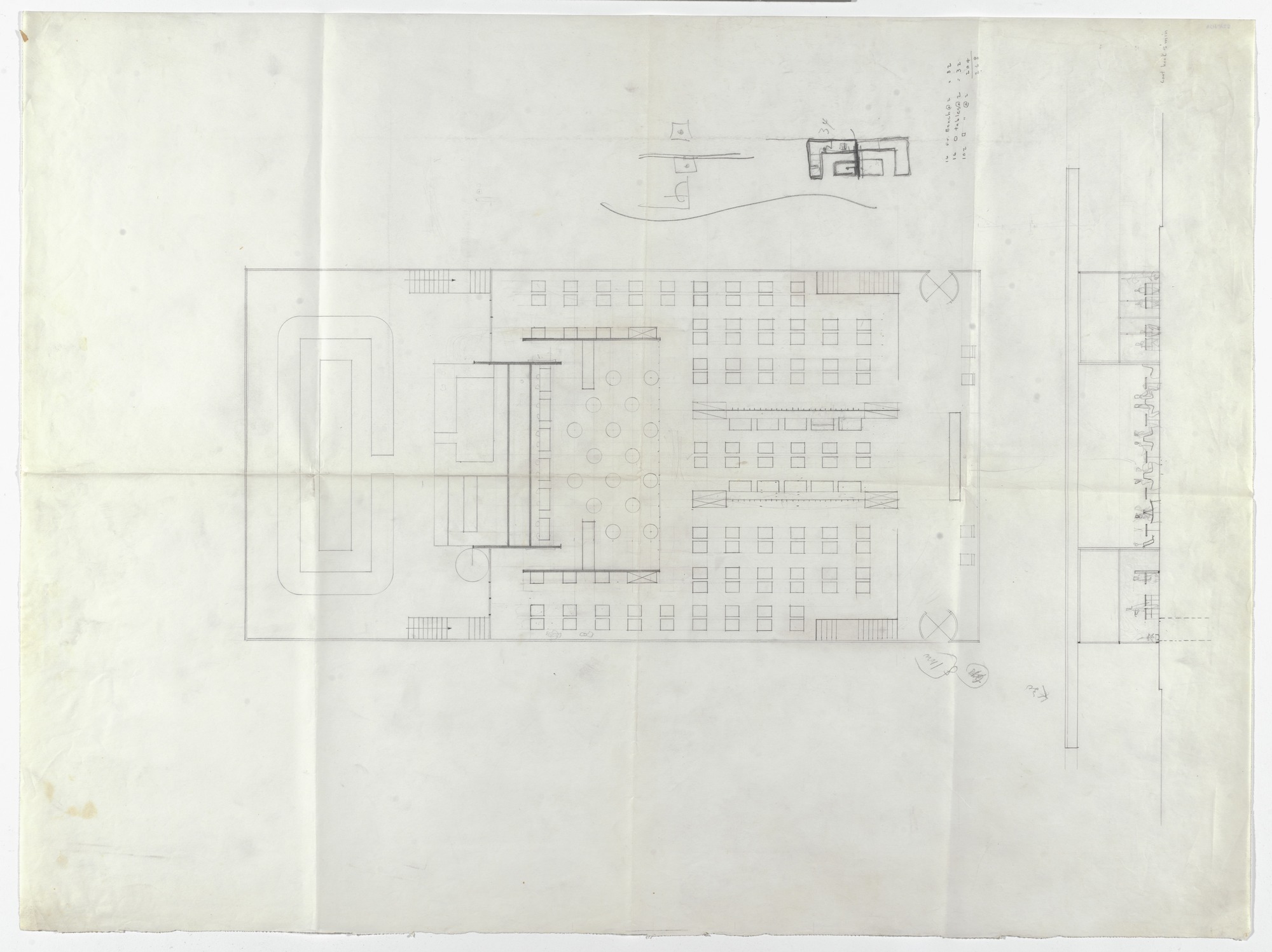

Now here’s where it gets really interesting. This is the overall plan for Rudolph’s “Floating Islands” project of 1952-1953:

Rudolph’s drawing for the Floating Islands project, for Leesburg, Florida. Image: Library of Congress

This is Interiors magazine’s description of the project:

"Architect Paul Rudolph intends to enliven one 180-mile stretch in the interior - between two of Florida’s most popular sights, Silver Springs and the Bok Tower - with an amusement center and tourist attraction where the main feature is Florida flora growing from earth materials supported by masses of floating roots commonly called ‘floating islands.’ The site has a 1000-foot frontage on two U.S. highways and easy access to a fresh water lake where fishing is excellent. Aimed primarily for sight-seers who want to stop for a couple of hours for food and rest to learn something fast about Florida flora, the center would provide a restaurant near the road for passing motorists as wells as those who stop to see the gardens. For entertainment and recreation there will be a variety of exotic floral displays, grandstand shows of swimming and diving, and boating and water skiing on the lagoon which leads to the large lake and then a string of lakes and canals for boat excursions."

From: "Baroque Formality in a Florida Tourist Attraction" Interiors magazine, January, 1954

When contemplating this composition, what immediately to mind are Wright’s designs that utilize circles, especially decorative designs, like this:

Frieze over the fireplace in the living room of the Wright-designed Hollyhock House, in Los Angeles, California. Image: Architectural Digest

Or this Wright design of a rug at the David and Gladys Wright house (incidentally, this house is one of our favorites) -

Image: Los Angeles Modern Auctions

And here is Wright himself, contemplating one of his most famous graphics, “March Balloons”:

Frank Lloyd Wright (photographed circa the 1950’s) looking at a design he’d submitted for Liberty Magazine in the 1920’s. Image: www.franklloydwright.org

Now, looking at these Wright designs, and looking at Rudolph’s plan for the “Floating Islands” project, do you see some formal resonance? Maybe a lot? We do. Hmmmmm!

But -

Isn’t history fascinatingly - for we learn that Wright had, earlier, worked on this project! Here’s what Christopher Domin and Joseph King tell us, in their wonderful book on Rudolph’s early work:

“Frank Lloyd Wright designed a sprawling scheme for this project in early 1952, which contained a central pavilion with a distinctive vaulted plywood tower, a series of cottages, and two pier-like motels with access from each room. After this project came in substantially over budget, Rudolph was brought in to reconceptualize the program and master plan for this combination highway rest stop, and tourist attraction near Leesburg in central Florida.”

Practical, budgetary, and programmatic challenges aside, one wonders what Rudolph thought (and felt!), knowing that he was supplanting the great Master himself. These fine historians go on to venture that Rudolph, in his design, might have been referencing Wright’s work (and mention several formally pertinent projects of Wright’s.) Or perhaps Wright’s original plan for this development was so strong, that Rudolph felt it provided a good and relevant parti for his own design? These are questions for which it is interesting to speculate - though they too have a circular quality.

PLATONIC PLEASURE

We were prompted to these rotund reflections by coming across this project, by the ever-fascinating MZ Architects:

Image: MZ Architects

It is their “Ring House”, a residential design for Riyadh. MZ describes it as:

“The proposed building consists of a cylindrical volume embracing a rectangular one. The cylinder acts as a protective closed wall with a single narrow opening serving as the entrance, while the inside rectangle accommodates fluidly all the house functions necessary for the everyday life of the artist: a bedroom, a bathroom, a living room, a kitchen and an atelier. The interior space interacts smoothly with the serene outdoor atrium, a large terrace garden with one symbolic tree and a circular water feature. By means of this composition, the ring-shaped structure figuratively resembles a cocoon ensuring a sense of intimacy and calmness for the house, that closes itself completely from the surroundings.”

The renderings make it look like the house, the courtyards, and the perimeter wall are made of concrete—and, if that’s the intention, this is certainly one of the most serenely elegant uses of concrete we’ve ever come across. MZ has other renderings for this superbly composed project—and we suggest you visit their website to see them (as well as explore the rest of their interesting oeuvre).

And that about rounds-out things for today…

Paul Rudolph: Designs for Feed and Speed

Front view of a model of a drive-in: the Cantor “HIWAY” restaurant, designed by Mies Van der Rohe. Image: The Museum of Modern Art

Floor plan and elevation of a drive-in: the Cantor “HIWAY” restaurant, designed by Mies Van der Rohe, pencil on tracing paper, circa 1945-1950. Image: The Museum of Modern Art

HIGH DESIGN FOR THE EVERYDAY

Famous architects—those operating at the very highest level of architecture-as-art - have designed for some surprising prosaic uses. Above is a model, plan, and elevation for Mies’ design for a highway drive-in. And did you know that he also - and we’re not kidding - did an ice-cream stand in Berlin? (Yes, it got built.)

Frank Lloyd Wright designed a gas station - which also was built:

Wright’s gas station, located in Cloquet, Minnesota. Image: McGhiever

Wright also designed a dog-house. And here’s a fascinating one designed by Philip Johnson, which is against a stone retaining wall near Johnson’s Glass House:

A Philip Johnson designed dog house—on the Glass House estate. Image: www.urbandognyc.com

By-the way, Rudolph said he’d be willing to design a dog house - if - he was allowed to design a very good and unique one. (We’re sure it would have been fascinating - but, as far as we know, he was never commissioned to do so.)

And, of course, famous architects have designed objects for everyday use - particularly furniture. We all know Mies’, Breuer’s, and Le Corbusier’s chairs, but what about Aalto’s tea cart - a very elegant design:

Alvar Aalto’s Tea Trolley 901, a design from 1936—and still manufactured and available. Image: www.Aalto.com

AND RUDOLPH DOES AS WELL

So it is no wonder that Paul Rudolph, when asked to design a donut stand, engaged in the project. Here is his perspective rendering, from 1956:

Paul Rudolph’s perspective rendering of a donut stand for Tampa, Florida. Image: Library of Congress

If one divided the arc of Rudolph’s career into geographically-based chapters (around the locations of his primary offices), one would say that he had three phases:

Florida (approx. just after WWII -to- 1958)

New Haven (approx. 1958-1965)

New York (approx.. 1965-his passing in 1997)

This project happened during the time his primary office was in Florida, and the preponderance of his clients in that state. It was there, centered in the Sarasota area (though extending outward to the rest of the state and beyond) that Rudolph started his career. Initially he was doing small houses, guest houses, beach houses… but his practice eventually grew to embrace all kinds of building types, from primary residences to schools, offices, and larger developments.

Rudolph’s designs for Florida are among his most creative and fascinating bodies of work. For a long time, one could only learn about them via delving into vintage professional journals—but an exceptionally fine book, covering that period, came out in 2002:

Image: Amazon.com

Paul Rudolph: The Florida Houses

by Christopher Domin and Joseph King, with photographs by Ezra Stoller. Published by Princeton Architectural Press

The book’s title undersells the book it bit, for (we’re happy to say) that the volume covers more than houses. For example: this donut stand. About it, they write:

"Rudolph, along with Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe, believed that even the most banal aspects of the American popular landscape such as fast-food restaurants and gas stations were worthy of an architect’s services. The Donut Stand, designed for a group of investors in Tampa, was commissioned as a prototype building to act as the marketing symbol for this roadside business. Rudolph hung a thin planar structure from four vertical steel supports, creating a veritable floating roof with a minimal, glass-enclosed interior space below. This project was designed in the Cambridge office at the same time as the Grand Rapids Homestyle Residence, with a similarly conceptualized open plan and restrained use of materials. A hastily rendered design drawing was presented to some of the investors, but was soon shelved after a payment dispute. By this time Rudolph opened his Cambridge, Massachusetts office to develop drawings for the Jewett Arts Center in Wellesley and later the Blue Cross Blue Shield Building in Boston, but many Florida projects from this period were also coordinated from this satellite studio."

Like dating a project - always a challenge in architectural history - the location where this project was done poses similar questions. As the authors point out above, when it comes to where this was designed, the story is a bit more complicated than the Florida-New Haven-New York triad.

At various times in his career, Rudolph had temporary satellite offices. (We tried to lay this out when we put together a timeline for the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s recent exhibit, Paul Rudolph: The Personal Laboratory - and found that it was challenging to figure-out the many locations where Rudolph and his team(s) worked.)

Even so, it is also hard to say that something was designed in one particular spot: architects are thinking/sketching/pondering design problems wherever they go. The documentary about Rudolph, “Spaces: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph” shows him sketching on the train. So even if the presentation materials for this donut stand were done in Cambridge, you can well guess that the place(s) where Rudolph was thinking about it was not geographically limited.

This was not Paul Rudolph’s first foray into roadside food facilities! The Library of Congress’ collection of Rudolph drawings also has a Tastee Freez stand, which he designed a few years before:

Paul Rudolph’s perspective rendering of a Tastee Freez stand, from 1954. Judging from the palm trees (in the background of the drawing), this too was for Florida. Image: Library of Congress

It’s interesting to contemplate what unites the two designs - and how they fit into Rudolph’s work and thinking. A few primary points might be mentioned:

The articulation of structure - as distinct from the planes of the roof/wall/enclosure/signage.

The play of opaque and transparent - which is strongly expressed in the graphic (solid black) contrast of the dark underside of the roof-planes.

The attention-getting nature of the design - even when done in a strictly High-Modern style, both buildings are well-planned to be noticeable from speedy passing traffic.

The inclusion of shade - especially important in a semi-tropical environment like Florida.

Never forgetting the human - both renderings include figures and seating which give a clear sense of scale (as well as conveying that these are not just abstract compositions, but rather for real use.)

Bauhaus-ian composition - which is hardly to be wondered-at, as Walter Gropius—founding director of the Bauhaus - was Paul Rudolph’s teacher when in Rudolph was in graduate school at Harvard.

High (end) or low; fast food or elegant settings; at intimate or gigantic scale - Rudolph, like any true design-master, could engage interestingly with any project.