Front view of a model of a drive-in: the Cantor “HIWAY” restaurant, designed by Mies Van der Rohe. Image: The Museum of Modern Art

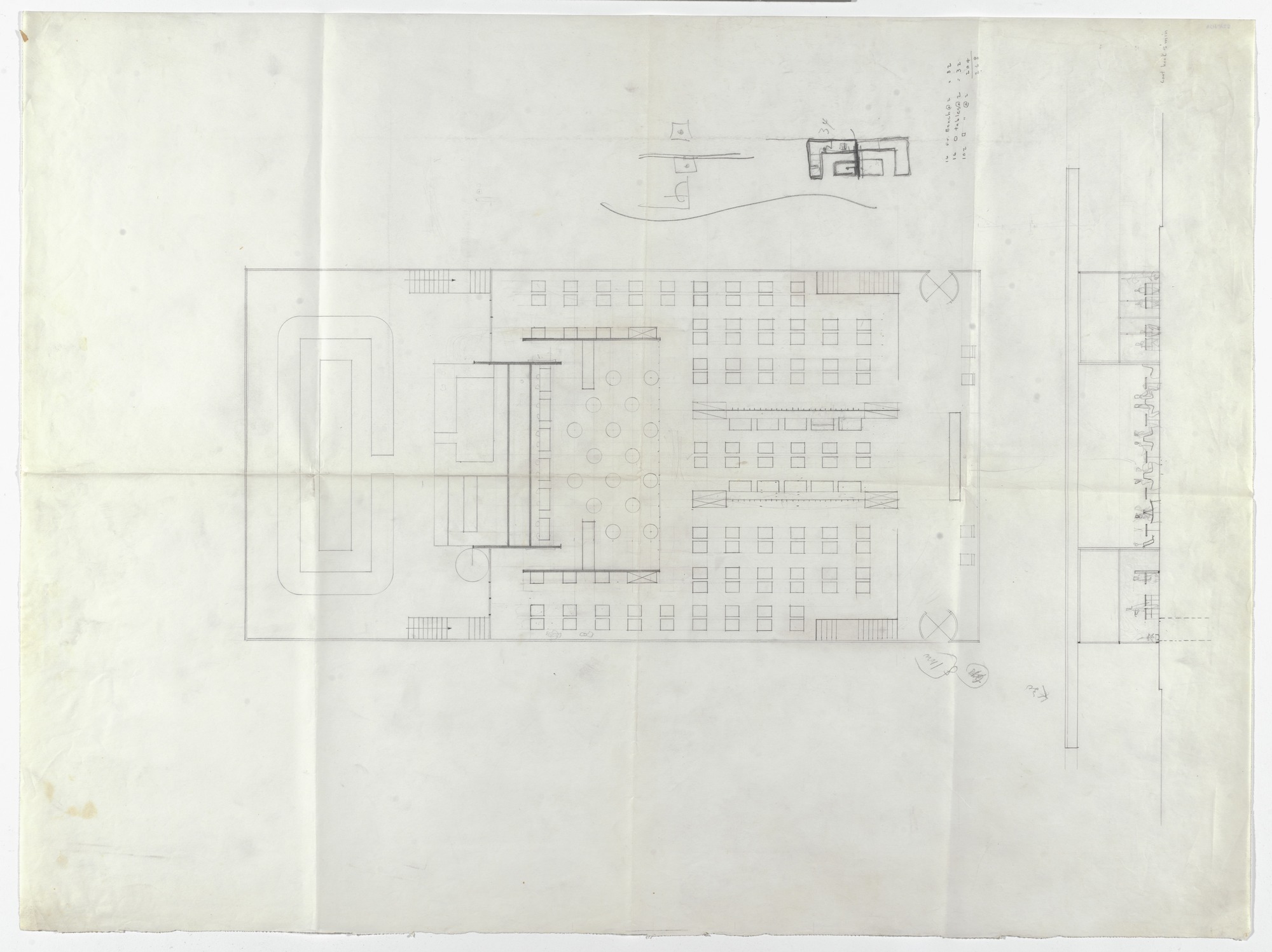

Floor plan and elevation of a drive-in: the Cantor “HIWAY” restaurant, designed by Mies Van der Rohe, pencil on tracing paper, circa 1945-1950. Image: The Museum of Modern Art

HIGH DESIGN FOR THE EVERYDAY

Famous architects—those operating at the very highest level of architecture-as-art - have designed for some surprising prosaic uses. Above is a model, plan, and elevation for Mies’ design for a highway drive-in. And did you know that he also - and we’re not kidding - did an ice-cream stand in Berlin? (Yes, it got built.)

Frank Lloyd Wright designed a gas station - which also was built:

Wright’s gas station, located in Cloquet, Minnesota. Image: McGhiever

Wright also designed a dog-house. And here’s a fascinating one designed by Philip Johnson, which is against a stone retaining wall near Johnson’s Glass House:

A Philip Johnson designed dog house—on the Glass House estate. Image: www.urbandognyc.com

By-the way, Rudolph said he’d be willing to design a dog house - if - he was allowed to design a very good and unique one. (We’re sure it would have been fascinating - but, as far as we know, he was never commissioned to do so.)

And, of course, famous architects have designed objects for everyday use - particularly furniture. We all know Mies’, Breuer’s, and Le Corbusier’s chairs, but what about Aalto’s tea cart - a very elegant design:

Alvar Aalto’s Tea Trolley 901, a design from 1936—and still manufactured and available. Image: www.Aalto.com

AND RUDOLPH DOES AS WELL

So it is no wonder that Paul Rudolph, when asked to design a donut stand, engaged in the project. Here is his perspective rendering, from 1956:

Paul Rudolph’s perspective rendering of a donut stand for Tampa, Florida. Image: Library of Congress

If one divided the arc of Rudolph’s career into geographically-based chapters (around the locations of his primary offices), one would say that he had three phases:

Florida (approx. just after WWII -to- 1958)

New Haven (approx. 1958-1965)

New York (approx.. 1965-his passing in 1997)

This project happened during the time his primary office was in Florida, and the preponderance of his clients in that state. It was there, centered in the Sarasota area (though extending outward to the rest of the state and beyond) that Rudolph started his career. Initially he was doing small houses, guest houses, beach houses… but his practice eventually grew to embrace all kinds of building types, from primary residences to schools, offices, and larger developments.

Rudolph’s designs for Florida are among his most creative and fascinating bodies of work. For a long time, one could only learn about them via delving into vintage professional journals—but an exceptionally fine book, covering that period, came out in 2002:

Image: Amazon.com

Paul Rudolph: The Florida Houses

by Christopher Domin and Joseph King, with photographs by Ezra Stoller. Published by Princeton Architectural Press

The book’s title undersells the book it bit, for (we’re happy to say) that the volume covers more than houses. For example: this donut stand. About it, they write:

"Rudolph, along with Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe, believed that even the most banal aspects of the American popular landscape such as fast-food restaurants and gas stations were worthy of an architect’s services. The Donut Stand, designed for a group of investors in Tampa, was commissioned as a prototype building to act as the marketing symbol for this roadside business. Rudolph hung a thin planar structure from four vertical steel supports, creating a veritable floating roof with a minimal, glass-enclosed interior space below. This project was designed in the Cambridge office at the same time as the Grand Rapids Homestyle Residence, with a similarly conceptualized open plan and restrained use of materials. A hastily rendered design drawing was presented to some of the investors, but was soon shelved after a payment dispute. By this time Rudolph opened his Cambridge, Massachusetts office to develop drawings for the Jewett Arts Center in Wellesley and later the Blue Cross Blue Shield Building in Boston, but many Florida projects from this period were also coordinated from this satellite studio."

Like dating a project - always a challenge in architectural history - the location where this project was done poses similar questions. As the authors point out above, when it comes to where this was designed, the story is a bit more complicated than the Florida-New Haven-New York triad.

At various times in his career, Rudolph had temporary satellite offices. (We tried to lay this out when we put together a timeline for the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s recent exhibit, Paul Rudolph: The Personal Laboratory - and found that it was challenging to figure-out the many locations where Rudolph and his team(s) worked.)

Even so, it is also hard to say that something was designed in one particular spot: architects are thinking/sketching/pondering design problems wherever they go. The documentary about Rudolph, “Spaces: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph” shows him sketching on the train. So even if the presentation materials for this donut stand were done in Cambridge, you can well guess that the place(s) where Rudolph was thinking about it was not geographically limited.

This was not Paul Rudolph’s first foray into roadside food facilities! The Library of Congress’ collection of Rudolph drawings also has a Tastee Freez stand, which he designed a few years before:

Paul Rudolph’s perspective rendering of a Tastee Freez stand, from 1954. Judging from the palm trees (in the background of the drawing), this too was for Florida. Image: Library of Congress

It’s interesting to contemplate what unites the two designs - and how they fit into Rudolph’s work and thinking. A few primary points might be mentioned:

The articulation of structure - as distinct from the planes of the roof/wall/enclosure/signage.

The play of opaque and transparent - which is strongly expressed in the graphic (solid black) contrast of the dark underside of the roof-planes.

The attention-getting nature of the design - even when done in a strictly High-Modern style, both buildings are well-planned to be noticeable from speedy passing traffic.

The inclusion of shade - especially important in a semi-tropical environment like Florida.

Never forgetting the human - both renderings include figures and seating which give a clear sense of scale (as well as conveying that these are not just abstract compositions, but rather for real use.)

Bauhaus-ian composition - which is hardly to be wondered-at, as Walter Gropius—founding director of the Bauhaus - was Paul Rudolph’s teacher when in Rudolph was in graduate school at Harvard.

High (end) or low; fast food or elegant settings; at intimate or gigantic scale - Rudolph, like any true design-master, could engage interestingly with any project.