Roberto de Alba’s book on the work of Paul Rudolph.. It covers projects from the final phases of Rudolph’s half-century career—and was done with the architect’s input. Fortunately, copies are still available from the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

A KEY WORK

The above book is important. It is one of the keys to understanding Paul Rudolph’s oeuvre, and well worth obtaining [which is not easy—but we can help you with that.]

But to unfold why it is so important needs a little background…

THE TRAJECTORY

Paul Rudolph said that his career would parallel Frank Lloyd Wright’s: early and growing fame (in both cases reaching international dimensions), then a lull, then a late flourishing—and finally a rising appreciation as historical assessments are made of 20th Century architects. It appears that Rudolph’s projection was right about the waves & troughs of both Wright’s and his own success. We should be clear that the rises and falls, that Rudolph was referring to, were in the domain of professional and public acclaim (with its real consequences for the number of commissions that came in—or the lack thereof). But he was not speaking of his or Wright’s creative powers: those remained undiminished (no matter the state of their success).

THE 3 PHASES

Rudolph’s half-century career is generally seen to be in 3 phases (related to where, geographically, he was situated):

Starting in Florida, right after World War II (centered in Sarasota—but extending throughout the state and beyond). In those years, he grew from being unknown-to-national stature.

Respect for his work increased to the point where he was selected to be the Chair of Yale’s school of architecture. It was at a relatively young age for that position—40—and he held that office from 1958 -to-1965. In that time his professional practice became extremely active. So he wound-up his Florida office and re-opened his firm in New Haven, near Yale.

Upon leaving the Chairmanship at Yale in 1965, he moved to New York. New York City remained his personal and professional home until his passing in 1997—though, for his work, he traveled nationwide and internationally.

Rudolph experienced his greatest success in the period that bridges from his time at Yale/New Haven -to- his initial five years in NYC: he had a chance to work on every kind of building type, do large-scale and prestigious commissions (including civic projects), and achieved world-encircling fame.

FAME, SUCCESS—AND THEN…

The archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation have clippings and reprints of articles on Rudolph, primarily from that 1950’s-to-1960’s era when it seemed that editors and writers couldn’t get enough of him. His multiple commissions, intense work ethic (which produced an incredible number of designs,) and legendary drawing skills resulted in widespread coverage in the press.

Paul Rudolph, and his Yale Art & Architecture Building, on the cover of Progressive Architecture in 1964—at the height of his fame.

But, after that, the lull which Rudolph spoke of became very much the case: he was virtually ignored by the same media that had helped give him fame. He always had some work, but by the 1970’s the river of large commissions began to evaporate. Yet his career extended for yet another quarter-century, to the time of his passing in 1997—and indeed there was a final flourishing, with large and significant commissions coming in during Rudolph’s final decade-and-a-half (mainly from overseas.).

AND NOW: A RUDOLPH REVIVAL

We seem to be in the midst of a Paul Rudolph revival. Rudolph would have been 100 in 2018, and his centenary featured two exhibitions (and the publication of corresponding catalogs) and a series of exhibit-related events (all sponsored by the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation); and an all-day symposium at the Library of Congress; and the latest issue of the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians features Rudolph’s Tuskegee Chapel on its cover (and contains a significant article on Rudolph by scholars Karla Cavarra Britton and Daniel Ledford,) In the previous year, a new anthology of Rudolph-focused papers had been published by Yale (“Reassessing Rudolph”.) All of this was preceded by Timothy M. Rohan’s comprehensive monograph on Rudolph, which had been published a few years before. And a new book on Rudolph, with an introduction by John Morris Dixon, has been announced for Fall 2019.

Two views of one of the exhibits occasioned by Rudolph’s 100th birthday: “Paul Rudolph: The Personal Laboratory.” The show was on display within the Rudolph-designed Modulightor Building in New York City, and featured original drawings and documents from the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, loans from friends, prints from the Library of Congress, and models commissioned especially for the exhibit.

THE BIG GAP

While Rudolph was extensively written and talked about during his most successful, mid-century period (with numerous articles and several books focused on him), there was not much available about that last period of his work, from about 1970 until his passing in 1997. Yet Rudolph was endlessly creative and still energetic when engaging with the projects of those final years—including ones of increasing scale and urban complexity. They show a designer who was able to make buildings and spaces of elegance, structural boldness, visual and spatial richness—and to work on an international scale.

FILLING THE GAP: DE ALBA AND RUDOLPH

Filling that informational gap is “Paul Rudolph: The Late Work,” by Roberto de Alba—a book which deals with a period of Rudolph’s work that had been unjustly under-covered and under-documented.

Roberto had met Rudolph when he was a student at Yale, through working on a 1987 exhibit, which he and a team of Yale architecture students had created about Rudolph’s iconic Yale Art & Architecture Building. Later, he spoke to the architect about doing a book on the later part of his oeuvre, and Rudolph agreed. Rudolph helped select the projects to be included, and when Roberto delved into the office’s files he found a treasure of creativity.

Roberto’s describes his approach to the book:

“In 1994 I approached Mr. Rudolph with an idea for a book that would document his work from 1970 onward. He seemed intrigued by my initiative, and we began working on an outline for the book. During the next three years, I visited Mr. Rudolph regularly, fist at his new office on 58th Street and later at his residence on Beekman Place, where he stored a huge number of drawing. We began by identifying a number of projects that would well represent the breath of his practice during those three decades Once the list was finalized, I searched the archives and office records systematically for every bit of information I could find relating to those projects. Rudolph was surprised by my interest in selecting “design process” drawings to represent the project but granted me the freedom to do so.”

He further explains:

“I saw the drawings, particularly the pencil sketches, and still see them today as evidence of his enormous talent and love for the art of building.”

In addition to the projects shown—the body of the book—there are further treasures in this volume: Mildred Schmertz’s insightful Forward, the penetrating Introduction by Robert Bruegmann, and the transcript of a fascinating Conversation between Rudolph and Peter Blake.

A BOOK THAT’S HARD TO GET—BUT IS OBTAINABLE THROUGH US

Yes, copies of Paul Rudolph: The Late Work are purchasable through the usual on-line booksellers: but only at high prices—often hundreds of dollars.

But there’s some Good News about that:

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation has copies available (and for a low price)—and you can order them on our website through this “shop” page.

Roberto de Alba’s book is a source for the study of Paul Rudolph—to see the level of creativity that Rudolph offered—even until his last days.

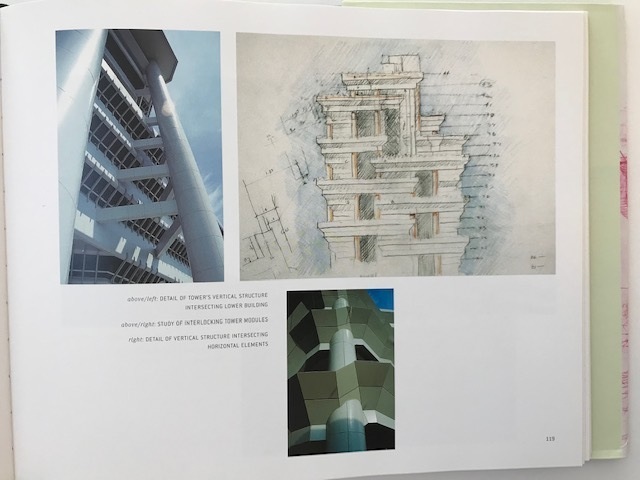

To give you a sense of the visual richness of the book, below are several selections: pages showing drawings and photos of some of Rudolph’s projects. On view here are: the Modulightor Building in New York; the Concourse Building in Singapore; and Rudolph’s own home: his “Quadruplex” townhouse & apartment on Beekman Place in NY (including a section drawing which shows the intensity with which he studied the possibilities for those spaces.)