Pantai Timur Surabaya: the design for a proposed new town for 250,000 people—a 1990 urban planning project by Paul Rudolph, to be located in Surabaya, the capital of the province of East Java in Indonesia. This city center drawing is one of several which Rudolph prepared for the project. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

WHAT WAS RUDOLPH? — HIS MULTIPLE ROLES

Rudolph is thought of in many ways—but urban designer is not often among the categories with which he’s linked. Yet he was intensely engaged—both intellectually and practically—in urban design. Here he’s shown, at far right, with key players in the development of the Boston Government Service Center, surrounding an architectural model of the complex—one of Rudolph’s strongest urban interventions.

Our ongoing research shows that Rudolph was many things. If you met him, he’d probably introduce himself as an architect (and in interviews he referred to himself as such)—but if one looks at his half-century career, what emerges are the multiple roles he played, both as a prolific professional, and in the lives of those with whom he interacted:

Architect— with well over 300 commissions, across the US and internationally, designing in a variety of building types and scales

Interior Designer— both as an aspect of his architectural projects, and as separate commissions

Furniture Designer— whether as built-ins or as freestanding units, Rudolph created numerous furniture designs for many of his buildings and interiors

Lighting Designer— virtually obsessed by light, Rudolph custom-designed light fixtures for individual projects; and later co-founded the Modulightor lighting company—for which he designed their line of lighting products and systems

Educator— at first, as guest lecturer or instructor at numerous schools; and later as the the Chair of Yale’s School of Architecture, where he revised and energized the school’s curriculum, staff, culture, and environment

Writer and Lecturer— although Rudolph worked on more-than-one book project, none were published in his lifetime—but he did speak in public, was interviewed, and published a number of illuminating articles in which he shared his thinking

Mentor— his former students and employees have testified to the power of Paul Rudolph’s example—as well as Rudolph’s ongoing, contributory relationships with them

Artist and Patron— creating murals for selected commissions, or working with artists whose artworks were integrated into his buildings

But where, in this broad list of his roles and engagements, is URBAN DESIGN?

Rudolph repeatedly focused his thinking, writing, and speeches on urban design—and judging from the way the topic keeps recurring in his public statements, it may well have been his most compelling concern. So it’s time that we consider Rudolph’s work as an urban designer.

PAUL RUDOLPH aND URBAN DESIGN: FOUR MODES

Rudolph’s’ engagement with urban design took several forms, scales and types—and it can be clarifying to categorize them into four modes:

1. URBAN DESIGN THINKING/PRIORITIES

2. URBAN INTERVENTIONS

3. COMMUNITY PLANNING

4. CAMPUS PLANNING

There are multiple manifestations of his work in each of these domains, and we offer some examples below (though this is not an exhaustive list of his ventures in each category).

1. URBAN DESIGN THINKING/PRIORITIES

Rudolph wrote & lectured throughout his career. This anthology, edited by Nina Rappaport, contains essays by him, interviews, and copies of his speeches. Numerous of those texts reveal his thinking on urban design.

Timothy Rohan’s monograph, on the life and career of Paul Rudolph, looked deeply into Rudolph’s urban design philosophy. In an important journal article, and in the book, he characterized Rudolph’s approach as “Scenographic Urbanism.”

Rudolph thought about what was wrong—and could be changed, improved, and fixed in our cities. Further, he was emphatic about what was missing in the Modern Movement’s approach urban design. He expressed his observations and thoughts in numerous speeches, writings, and interviews.

Key urban design issues for Rudolph, to which he kept returning, were:

The importance of the urban context, and seeing that even the most cleverly designed building is a part of larger whole. As Rudolph expressed it: “We think of buildings in and of themselves. That isn’t any good at all. That’s not the way it is, not the way it has ever been, not the way it will ever be. Buildings are absolutely and completely dependent on what’s around them.” -and- “Every building not matter how large or small, is part of the urban design.”

The existence (new to human history) of the automobile—and the need to work with that fact. But Rudolph was not speaking of just giving-in to the auto’s voracious demands for routes and resources (‘though he knew we’d have to deal with those practical matters). Rather: he was pointing to the new ways that we experience streets, architecture, and space when traveling in a car, and at speeds which citizens had never before known.

Coincident with that are the changes in the scale of the structures that were newly being constructed—works of a size unimagined by past ages. Of this he said: “Things are quite chaotic. We are faced with a vast change of scale, new building forms which have not really been investigated, and the compulsions of the automobile. When faced with the truly new, the serious architect must search for solutions equally dramatic.”

The need for variety with intensity, when shaping urban space. He expressed this point in this memorable passage: “We desperately need to relearn the art of disposing our buildings to create different kinds of space: the quiet, enclosed, isolated, shaded space; the hustling, bustling space, pungent with vitality; the paved, dignified, vast, sumptuous, even awe-inspiring space; the mysterious space; the transition space which defines, separates, and yet joins juxtaposed spaces of contrasting character. We need sequences of space which arouse one’s curiosity, give a sense of anticipation, which beckon and impel us to rush forward to find that releasing space which dominates, which acts as a climax and magnet, and gives direction.”

A deeper look into Rudolph’s thinking on urban design—and how he put those ideas into practice—can be found by reading his own words (in the book of his writings), and in the monographs on his career.

2. URBAN INTERVENTIONS—PROPOSED AND BUILT

Sometimes architects and planners get to work in “clean slate”, tabular rasa locations: sites where there is a relative lack of constraints about how a project is to be shaped, and what design decisions can be made. But that’s the minority of situations which architects urban designers find themselves in, and the preponderance of their work is within existing contexts which simultaneously pose multiple, convoluted, and intractable problems.

In such cases, some designers look at their work as “interventions”—a term more familiar from the cultures of medicine or therapy. But the concept has become a useful addition to the design discourse, as it can help designers to think—with clarity and responsibility—about the the limits of what should be done, the power(s) available to make change, and what is just and appropriate to propose or do.

Below are three examples of Rudolph’s urban design work, which could be characterized as “interventions":

Architectural Forum’s January 1963 issue Image courtesy of USModernist Library

RUDOLPH: A WASHINGTON INTERVENTION

John F. Kennedy, during his presidential inauguration auto ride in Washington, noticed the tawdry state of the capital’s most prominent streets and avenues—and asked/urged that action be taken to transform the city, so that it would live-up to its status as the capital city of the world’s most powerful free nation. This brought focus to the state of the city, and Architectural Forum devoted an entire issue to the design Washington, DC.

Architectural Forum, up until it ceased publication in 1974, was one of the US’ three major professional architectural journals, and was known for its “eye”: publishing some of the most interesting new buildings and interiors from around the world—and also for exploring the controversial issues of the day (and looking at their architectural and urban design implications). Thus it makes sense that they’d asked Paul Rudolph—the dynamic Chair of Yale’s School of Architecture, a prolific and creative designer, and a young star of the profession—to participate in looking at Washington, and proposing what might be done to fix it’s design problems while enhancing the city’s existing assets.

Paul Rudolph’s article, in that Washington-focused Architectural Forum issue, was titled “A View of Washington As A Capital—Or What Is Civic Design?” He reviewed the initial intentions of the city’s layout, as conceived by Pierre Charles L’Enfant (the original planner of the city, who’d received the assignment from George Washington)—and looked at the developing history of the city, the importance of density, the use of monuments, the state of official architecture, and the condition of major avenues and the Mall. He then offered suggestions on redeveloping a portion of Capitol Hill and the overall reorganization of that important central area.

Paul Rudolph’s article, in that Washington-focused issue of Architectural Forum, included this image: an aerial photograph of downtown DC, on which Rudolph drew his ideas for improving this part of the city. He focused here on the Capitol, the Mall, and surrounding buildings and key axes—and suggesting interventions that would increase the coherence of the ensemble. Image courtesy of USModernist Library

RUDOLPH: A NEW YORK INTERVENTION

Paul Rudolph’s LOMEX (Lower Manhattan Expressway) project was intended to address issues of cross-town traffic—but Rudolph took it to another level, with a visionary (if controversial) proposal: an intervention that would have transformed life in that southern section of the city. His design would have integrated transportation (of several kinds), housing, other building-function-types, and services—all within an innovatively shaped and planned infrastructure, and using a prefabricated modular construction system for the housing units. Of his proposal, Rudolph asserted:

“A conventional urban expressway might very well be more abusive to the city. On the other hand, building a new type of urban corridor designed in relation to the city districts through which it passes and engineered in such a way as to be capable of dissolving traffic and diminishing noise, exhaust, environmental and surface-street problems that have plagued the corridor area for decades might just be the most desirable approach.”

In Rudolph’s LOMEX drawing above, the routes between bridges at the edges of New York City’s Manhattan island are shown, surmounted by a titanic building project of housing and other building types. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

An important part of Rudolph’s concept for LOMEX was the housing system. Individual apartments, which he called “the brick of the future”: were to be manufactured and trucked to the site, and lifted into place onto structural towers. One can see several such tower assemblies in this model of a portion of LOMEX. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

LOMEX would have integrated housing with pedestrian, train, and automotive movement, and a full range of services needed to allow them to all function. All this was to be accommodated within a megastructure that was to span the width of Manhattan, as shown here in Rudolph’s perspective-section drawing. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

RUDOLPH: A BOSTON INTERVENTION

The BOSTON GOVERNMENT SERVICE CENTER is situated on a large triangular site, and was envisioned as a part of Boston’s downtown “Government Center” (whose other prominent Modern structure is the Boston City Hall.) About 2/3 of the complex was built in the way that Rudolph envisioned it. Within a set of muscular and sculptural concrete buildings are housed state offices offering varied services. The buildings enclose a quiet plaza, which was meant to be a peaceful respite in the city as well as part of the building’s entry sequence.

The size, location, and complexity of such a large complex was bound to have an effect on the adjacent parts of the city—and Rudolph thought carefully about its urban design aspects, and shaped and scaled the buildings based on his observations of Boston.

Here is some of his thinking about the design, taken from various public statements and interviews:

“The three buildings are purposely designed so that they form a specific space for pedestrians only and read as a single entity rather than three separate buildings. In terms of urban design, this is undoubtedly one of the first concerted efforts to unify a group of buildings that this country has seen in a number of years.”

“The irregular and complex form [of the plaza] is derived primarily from the irregular street pattern of Boston.”

“The generating ideas of most traditional cities are pedestrian and vehicular circulation, streets, squares, terminuses, with their space clearly defined by buildings. This means linked buildings united to form comprehensible exterior spaces. The Boston Government Service Center is the opposite of Le Corbusier’s dictum “down with the street.” It started with three separate buildings, their clients, architects and methods of financing. We didn’t build three separate buildings, as others had proposed, but one continuous building which defined the street, formed a pedestrian plaza. . . .The scale of the lower buildings was heightened at the exterior perimeter (street) so that it read in conjunction with automobile traffic (columns 60-70 feet high plus toilet and stair cores at the corners were used). The scale at the plaza was much more intimate using stepped floors which revealed each floor level, making a bowl of space. As one approaches the stepped six-story-high building it reduces itself to only one story. . . .”

Progressive Architecture published a 1964 article on the design for the Boston Government Service Center. LEFT: the opening page, featuring a photo looking down into a model of the full-block complex, which encloses a pedestrian plaza—and, below, the editors included intriguing comparison images of urban plazas in Sienna and Venice. Image courtesy USModernist Library. ABOVE: a site plan of the complex (circled in Red) and adjacent streets in Boston. For a comparison of scale, the Boston City Hall—itself a building of significant size—is shown at the lower-right (the rectangle circled in Blue.)

3. COMMUNITY DESIGN

There are several examples of Rudolph taking-on the design of whole communities, whether it be a new town, a new neighborhood, or a development so large that it could legitimately be considered a work that engages urban design challenges.

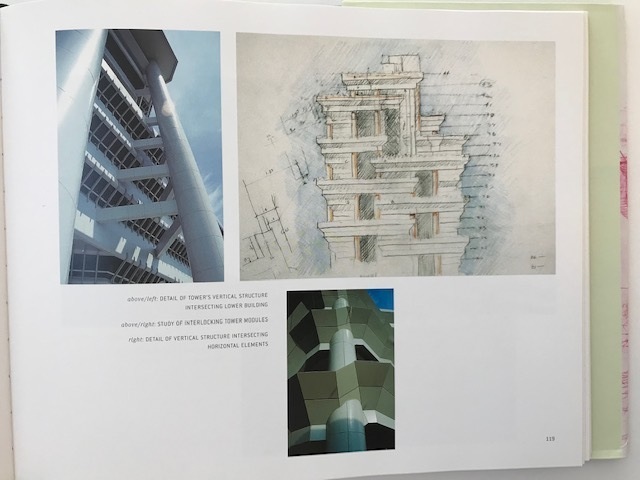

Probably the largest such assignment that he worked on was the design of new town in Indonesia for 250,000, people. Had it been built, it would have been a sizable new settlement—and below are drawings for that project.

Below that are several other projects where Rudolph is working at a large, urban scale—both with respect to the populations that would have been housed, and/or the geographical area that was to be covered.

Paul Rudolph’s Phase One study for the city center of Pantai Timur Surabaya—a proposed town for a quarter-million people in Indonesia. While this project never proceeded into construction, the urban ideas which it embodied are well worth studying. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Above is a further drawing by Rudolph—a site plan sketch—from his town planning project for the Pantai Timur Surabaya in Indonesia. Note: Larger versions of these drawings (this one, and the drawing at left) can be seen on the project page, here. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Buffalo’s Shoreline Apartments was a housing complex designed in 1969, a portion of which was completed in 1974. The full scheme (partially shown in the above model) included terraced high-rises around a marina, school and community center facilities, and low and mid-rise apartment buildings and townhouses, with green spaces woven through the site. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

A federally aided project in the late 60’s, designed to solve housing shortages in New Haven, Oriental Masonic Gardens offered 148 units of housing, ranging from 2-to-5 bedrooms. An attempt at bringing prefabrication to the housing crisis, the homes were made from 333 modules, placed in configurations that provided a separate outside space for each family. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

To be situated in the North-West portion of Washington, DC, the Fort Lincoln Housing project from 1968 was designed to be woven into the existing urban context, providing abundant (and much needed) housing, and offering a variety of apartment types. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

In 1974 Rudolph received a commission for an immense Apartment Hotel (a.k.a. the JERUSALEM HOTEL), which would have encompassed over 300 units, plus the many facilities to support them—all under a multitude of stone-clad, concrete barrel-vaults. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Comprising a master plan, and the design for townhouses, apartment houses, a hotel and boatel, and commercial spaces, Rudolph’s mid-60’s Stafford Harbor resort project in Virginia was the first time he’d ever worked on the planning of an entire town. Designed to take full advantage of its waterside location, it embraced the site’s existing topography. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Rudolph’s 1967 Graphic Arts Center project would have included 4,000 prefabricated apartment units, as well as spaces for a multiplicity of other functions. Stretching into the Hudson River, its vast scale can be perceived by comparing it with the World Trade Center complex, whose site plan (including the WTC’s two square towers) is shown at the right edge of the drawing. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

4. CAMPUS PLANNING: DISTILLED URBAN DESIGN

A large portion of Paul Rudolph’s oeuvre were educational buildings, done at all levels—from an elementary school to designing spaces for advanced research. Many were stand-alone buildings, but Rudolph was always aware (and respectful of) context. Even his most famous work, the Yale Art & Architecture Building (which has been cited as the paradigmatic example of individualism in design) is an example of Rudolph’s careful consideration of the setting—and one can see this in his drawings for the building, which purposefully showed the proposed design as it was to be situated within New Haven’s urban context.

More directly pertinent are his designs for whole campuses. The campus of a university, college, or educational institute has to simultaneously fulfill multiple functions: housing classrooms, laboratories, arts and athletic facilities, administrative space, a library, and—literally—housing for students (and sometimes faculty as well). Moreover, efficient and pleasant connections and travel between the buildings which house these activities—via interior and exterior routes—must be integrated into the plan. Finally, an oft-stated client goal is that the ensemble has a look of unity, so as to promote a sense of shared campus identity.

Accommodating such planning complexity, within a distinct area, is a concentrated version of an urban design problem—a distillation of trying to design a small city. Rudolph was commissioned to take on this challenge by several institutions, both across the US and internationally—with interesting results and in highly varying forms. Below are examples of his work in this domain.

The Tuskegee Chapel, of 1960, was one of the works for which Rudolph is most famed. But, over the decades, he was engaged by Tuskegee Institute for other buildings and purposes—for example: in 1958 they asked him to do the above Master Plan for the campus. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

If having “repeat customers” is the sign client happiness, then Tuskegee must have found Paul Rudolph quite satisfying to work with—a manifestation of which would be this 1978 commission to him for a Tuskegee Master Plan and College Entrance. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

The planning of the new campus for Southeastern Massachusetts Technological Institute—now UMass Dartmouth—commenced in 1963, and design work and construction continued over many years (and is ongoing). A pedestrian campus with an encircling parking system, it was conceived as a series of extended buildings based on a single structural-mechanical system, to be constructed of one material. A spiraling mall, created by the buildings, organizes the heart of the complex. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

The East Pakistan Agricultural University, south of the district town of Mymensingh (now Bangladesh Agricultural University) was a project from the middle 1960’s. It included a master plan to expand the existing campus, and the design of buildings for a full range of functions: auditorium, dormitories, laboratories, instructional spaces, and recreation facilities. A portion of Rudolph’s designs were constructed. Part of the model, for the overall design, is shown above. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

THE CONTEXT OF PAST AND CURRENT URBAN DESIGN THINKING, PLANNING, AND BUILDING

Paul Rudolph placed immense importance on urban design, and that necessitates being an astute and careful observer—as he Rudolph was—of the life and shaping of cities.

Cites are pivotal: the rise of civilization and cities go together, so a deep consideration of their forms is essential—and even pre (or non) urban settlements can have formal structures and layout rules of great civil sophistication.

This history—of the evolution and multiplicity of the forms cities have taken, and the forces which guided their shaping—is of enormous complexity, as is the literature which has been focused on these greatest of human artifacts. Influential books have been published (and continue to be) on urban design—often with implicit or outright declarations on how city-making should move forward. Among the most prominent have been Edmund Bacon’s Design of Cities, Kevin Lynch’s Image of the City, Rudofsky’s Streets for People, and works by Le Corbusier, Jacobs, Buras, Koolhaas, Howard, Rossi, and Mumford.

These authors/researchers/designers make profound contributions to our understanding of urban design—both as history and as lessons for today’s practice. But few offer the comprehensive, encyclopedic view of urban design history and form as to be found in a newly issued book: Urban Grids: Handbook for Regular City Design.

The result of a titanic 8-year study, and the work of an army-sized team of researchers and designers, this single volume is a deep review of urban design history, theory and practice—but the real value of the book is in its “case study” approach: comparing dozens of cities, world-wide, on the basis of their geometry, density, block configuration, street width and street-wall height, relation to topography, mix of uses, integration of various transport modes, growth patterns, and other factors. Over hundreds of pages, utilizing thousands of illustrations, this one volume makes available and synthesizes a body of information daunting in its richness and complexity—and will become an indispensable tool for all concerned with urban design.

Two adjacent pages from the book, on which the case studies of two cities—Algiers and Alexandria—are compared utilizing numerous diagrams and data.

A further spread from the book, from a section in which the history and evolution of urban design—including grid layouts—is explored.

BOOK INFORMATION AND AVAILABILITY:

TITLE: Urban Grids: Handbook for Regular City Design

AUTHORS: Joan Busquets, Dingliang Yang, and Michael Keller

PUBLISHER: ORO Editions

PRINT FORMAT: Hardcover, 8-1/2” x 12'“

PAGE COUNT & ILLUSTRATIIONS: 680 pgs., thousands of black & white and color illustrations

ISBN: 978-1-940743-95-0

ALTERNATE EDITION: A Spanish language version (“Ciudad Regular”) is also available:

PUBISHER’S WEB PAGE FOR THE BOOK: here

AMAZON PAGE: here

BARNES & NOBLE PAGE: here