An ornamental panel, designed by Louis Sullivan for the Schiller Theater (later known as the Garrick Theater) in Chicago, which opened in 1901. Photograph courtesy of Modulightor.

Visitors to the Modulightor Building—and particularly to the Paul Rudolph-designed duplex which is the spatial gem within it—are always curious about one of the objects on display here: a large (nearly 2 feet x 2 feet) panel, with a creamy finish and a complex composition of organic and geometric forms. The panel was designed by Louis Sullivan, and we thought you’d like to hear its interesting story.

ORIGINS: THE WORK OF ANOTHER MASTER

Louis Sullivan (1856-1924) was a renowned American architect, often considered one of the creators of the modern concept the skyscraper. Frank Lloyd Wright, who worked for him, asserted Sullivan to have been his greatest mentor, referring to Sullivan as “Lieber Meister” (beloved master)—and for Wright, a towering ego, it says something that he so strongly acknowledged another architect. Sullivan was based in Chicago and worked mainly in the Midwest—although he also designed major buildings as far away as Buffalo and New York City.

Sullivan was famous for his exuberant, lively, and inventive ornament, creatively integrating both natural (generally plant-based) and geometric forms. The ornament was used on the exteriors and interiors of his buildings, and was made from a variety of materials: terracotta, carved stone, plaster, as well as cast and wrought metals such as bronze and iron.

Adler & Sullivan—the firm he formed with his architectural partner, Dankmar Adler—designed the Schiller Theater (later known at the Garrick Theater) in Chicago, opening in 1901 with 1,300 seats. It was demolished in 1961, amid protests by preservationists. Although the building was not saved, a large number of ornamental elements from the building were recovered—including our ornamental panel made from cast plaster.

The Schiller Theater Building (later known as the Garrick) was designed by Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler of the firm Adler & Sullivan. Our “Sullivan panel” was part of the ornament of the theater’s proscenium arch. Image: Historic American Buildings Survey copy of a photograph taken circa 1900, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Louis Sullivan is also considered to be America’s prime practitioner of Art Nouveau in architectural design. Though often grouped with other Art Nouveau practitioners, Sullivan’s personal “system of architectural ornament” really grew from his individual philosophy, as well as his investigations of patterns, systems of geometric and natural generation and growth, and by plant forms—and one can readily see that in his composition of this decorative panel.

This view, of the theater’s interior, shows that Sullivan used a variety of cast plaster ornament. The proscenium’s design (seen at the upper-right) is composed of a series of recessing, concentric arches, and one can see that those arches are lined by repeated castings of our “Sullivan panel.” Image: Historic American Buildings Survey copy of a photograph taken circa 1900, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

FROM CHICAGO -TO- YALE

When the Schiller/Garrick was demolished, at the beginning of the 1960’s, efforts were made to create a comprehensive record of the building (as well as to preserve as many examples of the ornament as possible.) Heroic in this work was Richard Nickel (1928-1972)—the Chicago-based photographer and preservationist. It is to him that we owe much of the documentation and artifacts which survive of Chicago’s lost architecture, as well as his helping to create the preservation movement.

Paul Rudolph took over as Chair of the architecture school at Yale in 1958—and he was to have a long run as head of the school, not leaving the post until 1965. While there, he achieved what is probably the dream of any chair or dean: to design his own school building. The design process began shortly after he started at Yale, and the building—now known as Rudolph Hall in his honor—was completed in 1963, almost instantly becoming one of the most famous Modern buildings in the world.

Although the building rapidly became an icon of the Modern Movement, Rudolph had placed examples of vintage architectural fragments, ornament, and sculpture throughout the building—including examples of Sullivan ornament. We don’t know the exact process whereby the Garrick panels got from Chicago to Yale, but the timing was right: the theater was demolished about the same time that Yale’s school building was being constructed and fitted-out. [Perhaps there was some intersection between Nickel and Rudolph?]

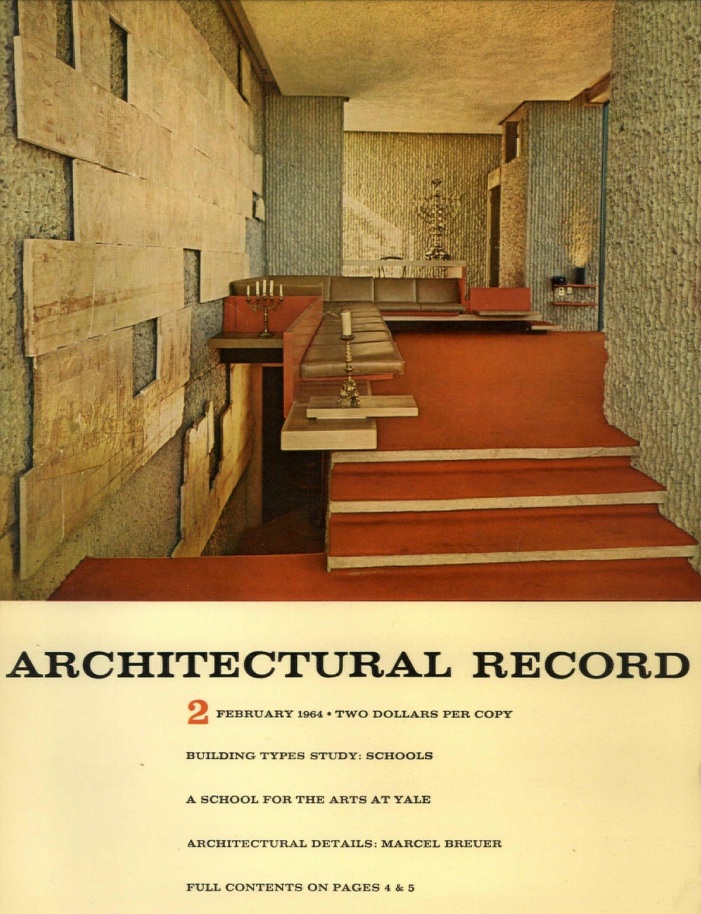

The Yale Art & Architecture Building—Paul Rudolph’s most famous design, and an icon of Modern architecture—was featured in Architectural Record’s February 1964 issue. The cover shows one of the interiors in which, as with many of the building’s other spaces, Rudolph had incorporated vintage ornament, fragments, and objects. Image: Courtesy of USModernist Library.

Placing these objects into such an educational setting aroused responses of a “How could you!” flavor (as some thought that their inclusion was a betrayal of Modern principles)—most pointedly from Yale teacher, artist (and Bauhaus alumnus) Josef Albers. [The controversy is covered in recent book from Princeton University Press, Plaster Monuments: Architecture and the Power of Reproduction by Dr. Mari Lending, a professor of architectural history and theory at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design.]

FROM YALE -TO- RUDOLPH

Ernst Wagner, founder of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, tells us that when Rudolph left Yale in 1965, he was told that he could take anything he wanted—and the Sullivan panel was among the things he brought with him to his new home, New York City. In his New York rental apartment, Rudolph used the panel in a unique way: to form the back plane of his living room sofa. Actually, the images we’ve seen of that room show several panels in-a-row, forming that sofa back—so we don’t know if Rudolph owned several original Sullivan panels -or- if he had multiple castings made.

An article in the May, 1967 issue of Progressive Architecture magazine focused on innovative interiors—including Paul Rudolph’s floor-through apartment in a townhouse near the UN. In this view of the living room, the sofa back---made of a series of Sullivan panels—can be seen on the far left. Image: Courtesy of USModernist Library

THE PANEL GOES UPSTAIRS

Later (in collaboration with Ernst Wagner) Rudolph purchased the townhouse in which he’d been renting: 23 Beekman Place—and he went on to create his famous “Quadruplex” penthouse apartment atop the building. The Sullivan panel, placed at the Eastern end of the living room, acted as a strong formal focus point.

Paul Rudolph’s section-perspective of his Beekman Place “Quadruplex” apartment. In this longitudinal section, looking South, one can see the Sullivan panel at the lower-left. Image: Paul Rudolph Archive, Library of Congress – Prints and Photographs Division

A view of the Living Room in Rudolph’s Quadruplex apartment, looking East. The Sullivan panel at the end of the room, in front of the main window which looks out over the East River. Photograph by Ed Chappell

FROM QUADRUPLEX -TO- DUPLEX

When Rudolph passed in 1997, Ernst Wagner was one of his heirs. A number of Rudolph’s possessions—including objets d’art from Rudolph’s Quadruplex apartment, passed to Wagner, and among them was the Sullivan Panel (with the mounting frame which Rudolph had designed for it).

The duplex residential spaces, within the Modulightor Building, were originally designed to be revenue-producing rental apartments, but Ernst Wagner (who’d become the sole owner of the building with Rudolph’s passing) began to occupy those spaces in 2000, opening up the doors between the north and south apartments so that it became one spacious, light-filled duplex. He furnished them with things he’d collected, as well as the legacy of objects and antiques he’d received from Rudolph—including the Sullivan panel—and that’s where the panel resides today.

The Sullivan panel, where it now resides in the living room of the Rudolph-designed duplex within the Modulightor Building. Photograph: courtesy of Annie Schlechter

SEE THE PANEL IN PERSON

The Modulightor Building—including the Rudolph-designed duplex (with the Sullivan panel) can be visited, either by attending our monthly Open House, or by scheduling a private tour. Find out about that through the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s Visit page on our website.

READ ALL ABOUT IT

This American Life’s Ira Glass, Chris Ware, and Tim Samuelson have produced a densely rich book-DVD set, “Lost Buildings,” which focuses on Sullivan’s work—including the efforts that Richard Nickel made to save that built heritage (and the Schiller/Garrick building receives a lot of the book’s attention).

“Lost Buildings” is a book-DVD set, which focuses on the lost work of Louis Sullivan in the Chicago area. The Schiller/Garrick building—and especially its ornament—is one of the buildings which the book delves into.

If you’d like to get a copy, you can obtain it directly through This American Life’s website. Copies are also often available through Abebooks or Amazon—and the quickest way to locate them on those sites is by putting these 4 words into those pages’ search box: lost buildings collaboration ware

AND GET THE PANEL!

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, in collaboration with Modulightor, is also making available full-size reproductions of the Sullivan panel. They are fabricated by an art-casting firm (who also applies a finish which matches the original with great fidelity), and a portion of each sale goes to support the work of the Foundation. [If you’d like to discuss obtaining one of them, please contact us at: office@paulrudolphheritagefoundation.org ]