The Edersheim Residence in Larchmont, New York in 2020. Photograph by Filip Michalowski of CT Plans, courtesy Houlihan Lawrence

Paul Rudolph’s Edersheim Residence at 862 Fenimore Road in Larchmont, New York is for sale.

The original house was constructed in 1958 and owners Maurits and Claire Edersheim hired Rudolph to design alterations to the property in 1982, following his interior renovation of their New York City Apartment on Fifth Avenue in 1970.

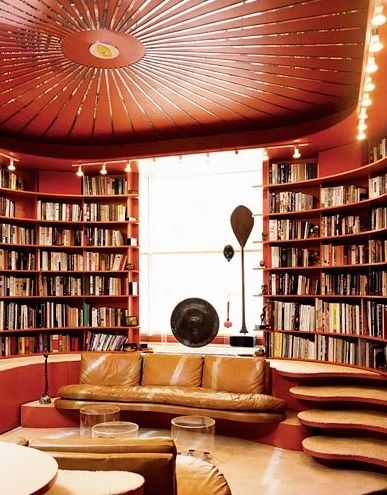

The Edersheim apartment in New York City in 2019. Photos by Ethan Shapiro © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

The Edersheims requested Rudolph design alterations and additions to the property again in 1989 and 1991. Original Rudolph designs include a pool/guest house, main residence entry, covered porch, expansive built-ins, skylights, interior lighting and a complete renovation of the main structure.

The Covered Porch under construction. Photo by R.D. Chin from the Archives of The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

The Pool/Guest House under construction. Photo by R.D. Chin from the Archives of The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

The Pool/Guest House under construction. Photo by R.D. Chin from the Archives of The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

The Edersheims would become some of Rudolph’s most faithful clients, choosing him to design several projects including an office suite for Mr. Edersheim at the Salomon Smith Barney office in New York’s World Trade Center Complex in 1994.

The compound (renovated in 2020) includes the Main Residence, a separate Apartment/Office and a Pool/Guest House. This is a rare opportunity that is perfect for sheltering in place.

Located in Larchmont, NY - just north of New Rochelle and New York City - the home is sited on a 2.49 acre landscaped lot and is listed for $6.4 million USD.

The property includes indoor & outdoor swimming pools, wet/dry sauna, media room, gym, and multiple work spaces. The open flow floor plan features several additions designed by Paul Rudolph. The Master Suite includes a 21 jet tub, steam shower, rain/body showers, dual water closets, towel warmers, vanity/ dressing area and attached closets.

About 10,000 sq feet of outdoor living space includes a 1,000 sq ft screened-in outdoor covered porch with an outdoor kitchen for entertaining.

The residence is located on a unique 2.49 acre private landscaped property in Larchmont and is an easy NYC commute with access to golf, country clubs & the water.

You can learn more about the Edersheim Residence (including more images) at the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s page for the property’s sale here.

You can also reach out to us at office@paulrudolphheritagefoundation.org for more information.