Frank Lloyd Wright (left) with Philip Johnson

FRANK AND PHILIP

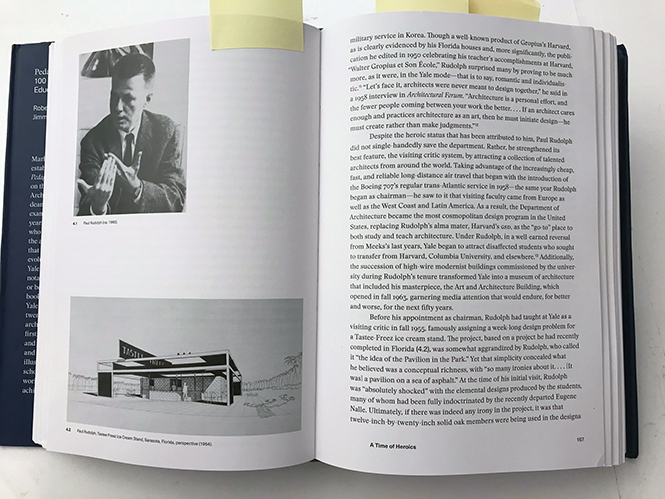

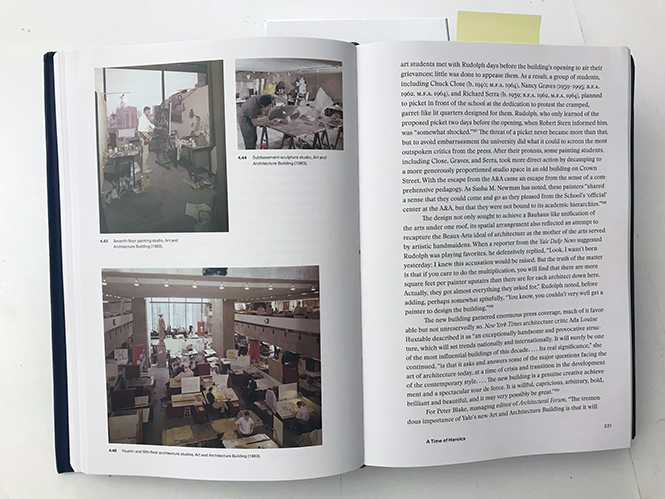

Wright and Johnson: given their contrasting personalizes, background, design orientations, and different generations—they were born nearly 40 years apart—they were not a likely pair.

Yet they had decades of interaction, and two main factors contributed to that ongoing phenomenon:

In some ways, architecture is a small world. If you’re in the field, chances are that you know (or know of) scores and even hundreds of colleagues though journal articles, exhibitions, lectures, teaching, organizations, juries, conferences - and now, on-line. And if you’re famous (or ambitious and working on it), it’s likely that you’ve personally met and engaged with each other at the kinds of venues mentioned above. That, in turn, begets even more such occasions and encounters: further exhibits, more meetings, additional panels & symposia, recommendations for fellowships, new conferences… as well as mutual acknowledgment on social media.

Charming, social, strategic, ambitious, energetic, mentally sharp - that set of characterizations can accurately be applied to both Wright and Johnson. Creatively, Wright was a force-of-nature - and he can be justly included as one of Modern architecture’s foundational trio (the other two, generally selected for that pantheon, are Mies and Corbusier) And Johnson - whatever you think of his design oeuvre (and we do like some parts of it) - can be well described as an architectural entrepreneur. Not just in the matter of obtaining clients, but rather in the broadest sense of his working to influence & explore culture through exhibits, writing, curation, making connections, public pronouncements, and pouring his personal resources into many projects (a.k.a.: various kinds of patronage.)

Wright did those things too, but with Johnson it was a bit different. It seems funny to say it, but in a way Johnson was the less selfish of the two. Wright was relentlessly focused on himself and his self-designed community/universe. But Johnson - while no slouch when it came to self-promotion, and in actively seeing out clients for his growing practice - was also sending energy outwards. So the exhibits, books, organizations, and other projects to which Johnson contributed or organized were not always just about him—and that’s a contrast with Wright.

There were a variety of occasions and reasons for them to interact - as recounted in a full-length study of the pairing by Hugh Howard.

Hugh Howard’s recent book on Wright and Johnson, “Architecture’s Odd Couple” Photo: Bloomsbury Press

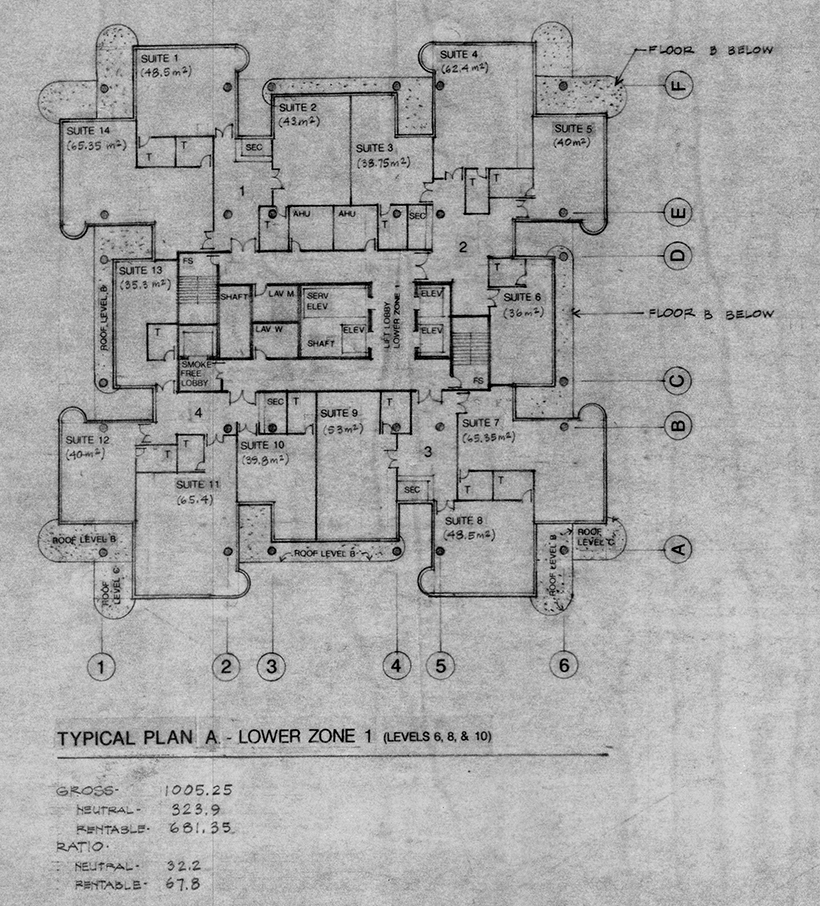

Some of Johnson’s projects brought them together, most notably MoMA’s “Modern Architecture: International Exposition” of 1932, for which Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock were the curators (which also resulted in an equally famous and influential book & phrase: “The International Style”). Wright, possibly annoyed at not being the show’s center of attention, was grouchy about the whole thing and seems to have played “hard-to-get” - but he did eventually decide to take part in this historically significant exhibition.

Wright’s work, as shown in MoMA’s architecture exhibition. Photo: The Museum of Modern Art, New York

PAUL AND PHILIP

A snapshot of Philip Johnson (with folder in hands), Paul Rudolph (in center, on stool), and Vincent Scully (to the right of Rudolph), at a Yale architecture school jury in 1960. Photo: Stanley Tigerman

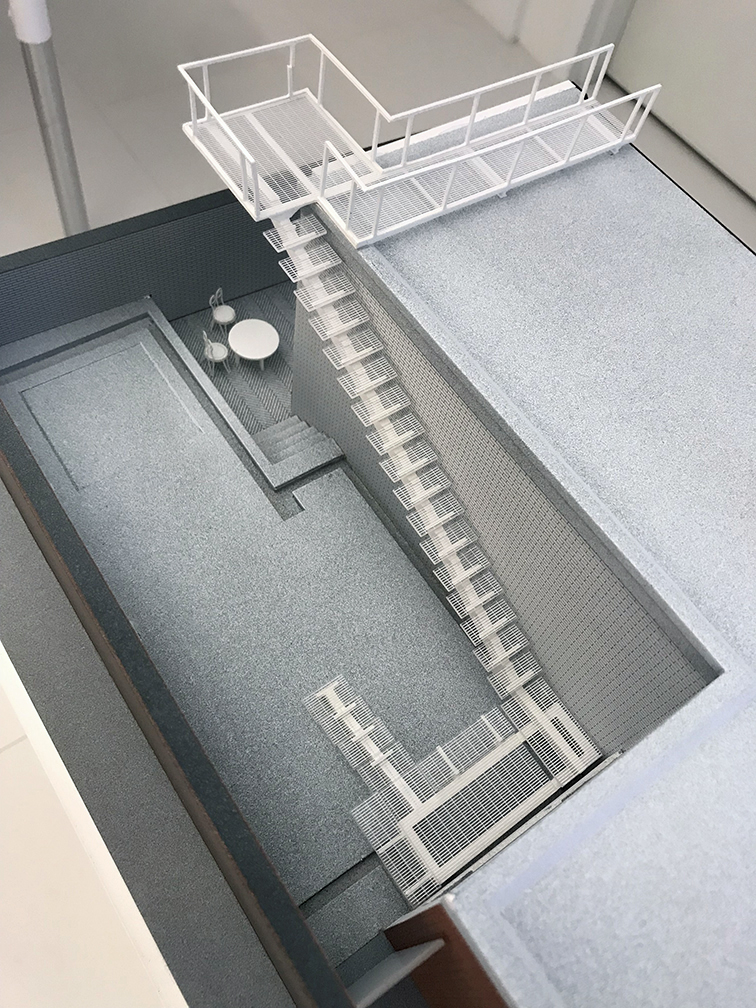

Paul Rudolph and Johnson were old friends, rivals, and sociable sparring partners. For example: Rudolph invited Johnson to teach at Yale; they’d dine together at a pub about midway between their Manhattan homes; they’d poke fun at each other’s work; and Rudolph was a welcome guest at Johnson’s famous Glass House estate in New Canaan.

Sunset at Philip Johnson’s Glass House. Photo: Arthurious.com

A WEEKEND IN THE COUNTRY

A special 1996 issue of ANY [Architecture New York] magazine was devoted to celebrating Philip Johnson’s 90th birthday. 33 essays, from luminaries ranging from Stanley Tigerman -to- Zaha Hadid -to- Hans Hollein -to- Kevin Roche (and 29 more!) offered their memories, thoughts, anecdotes, and tributes to Johnson - including one from Paul Rudolph, titled “A Sunday Afternoon.” As you’ll see, it records a unique occasion when the three of them - Wright, Johnson, and Rudolph - were together:

Now that’s what we’d call a perfect day.