The state wants to sell parts of Rudolph’s Boston Government Service Center to a developer—and all their “alternatives” include demolition to part of the site. You can attend a presentation in Boston—and show your support for preservation.

Update: Development "Alternatives" Report Released for Rudolph's BOSTON GOVERNMENT SERVICE CENTER

Kate Wagner and McMansion Hell: Deeper Into the question of Brutalism (and what it's NOT)

Concrete for the Holidays (a gift suggestion!)

Brutalism - In Home Decoration ? (Yes.)

S.O.S. Update # 4 : Proposed Demo & Development at Rudolph's Boston Government Service Center

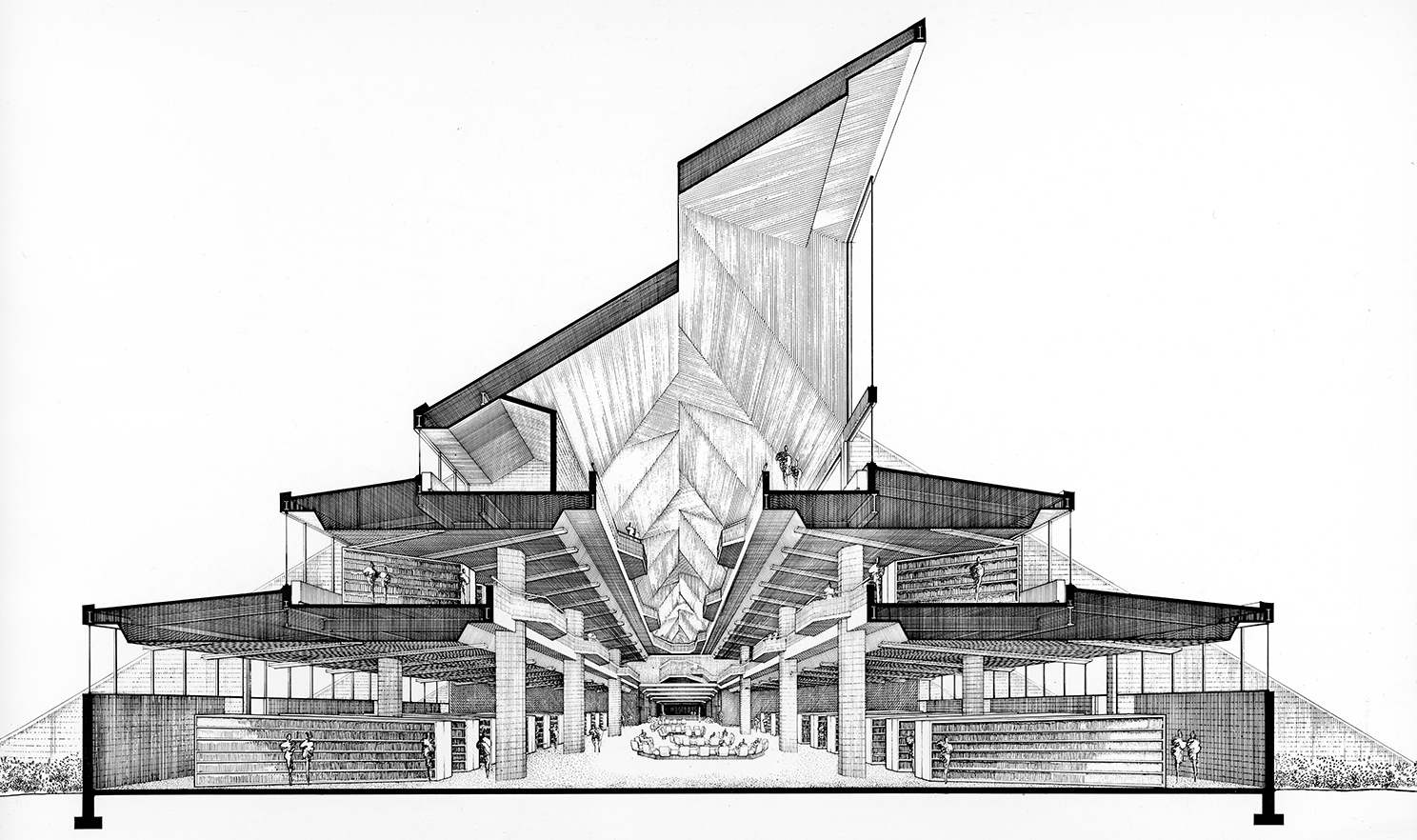

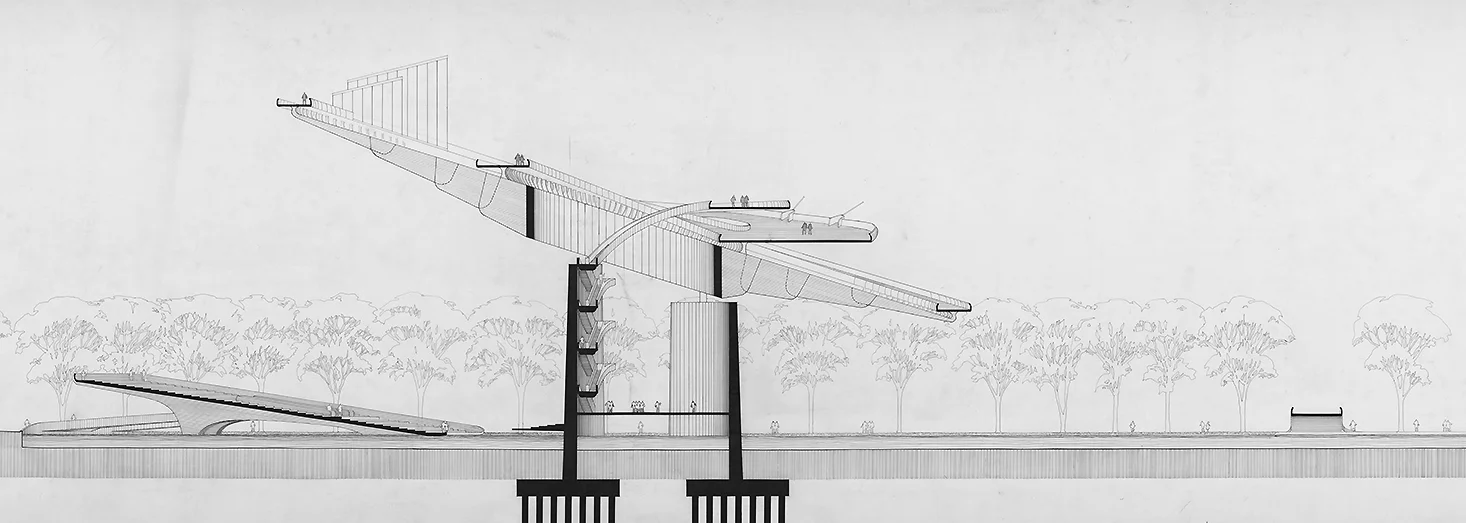

Paul Rudolph’s original, overall conception for the Boston Government Service Center included a tower (which, unfortunately, was not built). The proposed development of the site brings up a serious question: Would/could new construction be as harmonious (with the existing buildings) as the design Rudolph created? Rendering by Helmut Jacoby. The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

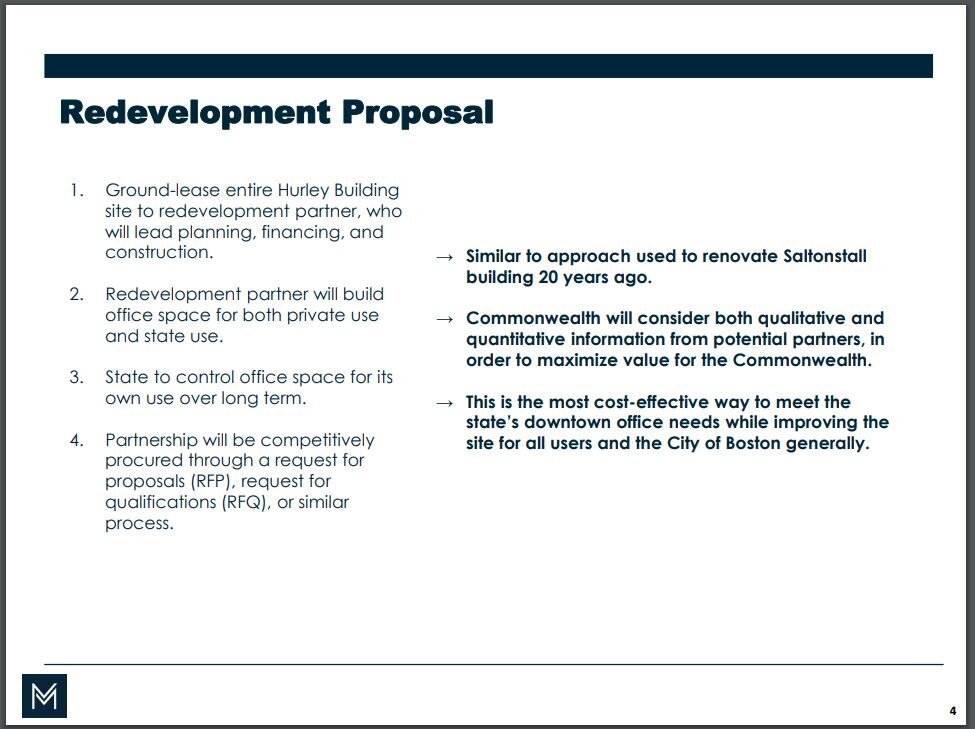

In this developing story, the state of Massachusetts’ Division of Capital Asset Management & Maintenance issued a power point presentation about their redevelopment proposal for the Boston Government Service Center—one of Paul Rudolph’s largest urban civic commissions. We’ve been looking at the various slides in their power point “deck” and examining the various assertions they make—and bringing forth our sincere and serious questions.

In previous posts we’ve looked at the ideas (as shown in their presentation) on the current building, development, how current occupants of the building would be handled, etc… —and offered our concerns about each.

Let’s look at the their next two slides:

WHAT WILL BE DEVELOPED THERE?

Following each of the slide’s points, we offer responses/questions:

The redevelopment partner that the state chooses will be responsible for planning, financing, and permitting the redevelopment.

The key word here is: planning—and we ask: How are they getting input during that process? And from what stakeholders? (and how is it weighted, and who has a veto?)

This process will be subject to Large Development Review by the Boston Planning and Development Agency under Article 80, and to review by MEPA.

It would be useful to all parties to lay this out in more detail, so that all can see what’s involved—and where (at what points) real input and interventions can be offered to improve all proposals.

The site is zoned for more intensive use than is currently realized. – Allowable Floor Area Ratio (FAR) is 8-10 (currently ~2.0).

Ideas about zoning (especially levels of density) change over time, as different planning theories and urban design schools-of-thought become popular and wane. Moreover, the question of desirable density is subject to political pressures. What makes a good building/public space/block/street is not always determined by zoning codes, equations, or the theories of the moment.

Generally, height is limited to 125’ towards the street edges, and up to 400’ on the interior.

Perhaps they’re saying that those are the current code’s height limits, which a developer must work within. It would be useful to know if that is the intent, or if there are other consequences.

Planned Development Areas (PDAs) are allowed on a portion of the site. The redevelopment partner may use the PDA process in order to allow the site to be more thoughtfully planned.

The consequences of this statement are not clear, and it would be useful to know more about PDA’s. The phrase “more thoughtfully planned” begs the question: more than what?

And let’s consider their next slide:

hISTORIC PRESERVATION APPROACH

Following each of this slide’s points, we offer our responses/questions:

DCAMM’s approach to redevelopment will acknowledge the architecturally significant elements of the Hurley-Lindemann site, while addressing its flaws.

The language begs the question about the building having flaws—-whose nature and quantity is unspecified. Any building can probably be renovated over time, and made more congruent with current needs—and we need clarity on what’s claimed and what’s proposed.

The Government Services Center complex was planned by prominent architect Paul Rudolph.

Yes, Paul Rudolph conceived of the overall plan and design: it is one of his major urban-civic buildings.

The complex was meant to include three buildings, but only two of the original buildings were built (Brooke courthouse was added later).

It is unfortunate that the scheme was not fully realized.

The Lindemann Mental Health Center was also designed by Rudolph, and is more architecturally significant than the Hurley building.

This project was designed as a set connected buildings that are strongly related—with a level of coordination in design that would create a feeling of wholeness to the block. That sense of wholeness is fundamental to good architecture—and is something to which Paul Rudolph was committed. Setting-up one building against the other is contrary to the way the complex was conceived and designed—and one can even see this from Rudolph’s earliest sketch.

DCAMM is required to file a Project Notification Form (PNF) with the Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC). DCAMM will then work with MHC to develop a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) regarding future development at the site.

It would be useful to know more about this process, how it functions, and how input is received from all interested parties—and, in this case, what ingredients go into creating a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA).

NEXT STEPS: LISTENING AND ACTING

We will continue to respectfully review the state’s proposals—and raise sincere questions when appropriate.

If you have information or insights to contribute, for preserving this important civic building by Paul Rudolph, please let us know at:

office@paulrudolphheritagefoundation.org

Paul Rudolph’s original sketch for the layout of the Boston Government Service Center. The drawing summarizes the overall concept of having the set of strongly related buildings wrapping around the triangular site—with a large, open plaza in the center.. A tower is indicated by the hatched pinwheel-shape toward the middle. © The estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

S.O.S. Update # 3 : Proposed Demo & Development at Rudolph's Boston Government Service Center

The publicly accessible courtyard at the center of of Paul Rudolph’s Boston Government Service Center. While one sometimes hears accusations against the building, it should be equally noted that it is also a public oasis of green and peace. Photo courtesy of UMASS

In this developing story, the state of Massachusetts’ Division of Capital Asset Management & Maintenance has issued a power point deck about their redevelopment proposal; We’ve been looking at the various assertions they put forth—and offering our sincere and serious questions and concerns.

We’ve looked at (and offered our questions about) the first set of their powerpoint slides, and then did so with a second set.

Let’s look at the next two:

PLANS FOR CURRENT BUILDING OCCUPANTS

Following each of the slide’s points, we offer responses/questions:

DCAMM will work with all occupants and relevant union leadership to find temporary and permanent relocation space that suits agency operational needs in a cost-effective way.

With any relocation of multiple departments and numerous staff, the question must be asked: How much disruption to services (and employee lives) will be caused by this? -and- For how long? We understand that promises based on projected timelines are offered in good faith—but often projects are delayed (sometimes for years) by unexpected factors (for example: construction delays, changing budgetary priorities, changes in administrative structure, changes in leadership….) So: however long the relocation/disruption/dislocation has been projected to last, in reality is could go on for much longer.

Current plans entail the majority of EOLWD employees who currently work at the Hurley Building returning to the redeveloped site.

Since the development plans are not even sketched out, on what basis can this promise be made?

No state employees will lose their jobs as a result of this redevelopment.

Same as above: plans are not even known—on what basis can promises be made?

Employees will remain in or near Boston, in transit accessible locations

What’s meant by near and transit accessible needs to be defined.

And let us consider the next slide:

US DEPARTMENT OF LABOR

Following each of this slide’s points, we offer our responses/questions:

The US Department of Labor funded the initial construction and site acquisition of the Hurley Building, and still has a significant amount of equity in the site.

It would be useful to know the extent of the equity, and the tangible consequences of this statement.

As required by federal rules, the Commonwealth is working with USDOL to ensure that federal equity is used to further the work of the Commonwealth’s Labor and Workforce Development agencies.

Here too, it would be useful to have things made more explicit: What rules are being invoked? What federal equity is being referred to? and overall: What are the consequences of this statement?

NEXT STEPS: LISTENING AND ACTING

We will continue to respectfully review the state’s proposals (and raise questions when items need review or clarification.)

If you have information / resources / insights to contribute, for preserving this important civic building by Paul Rudolph, please let us know at:

office@paulrudolphheritagefoundation.org

Even with a few signs of a coming Fall, the center plaza’s oasis is still very green! Photo © the estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

S.O.S. Update # 2 : Proposed Demo & Development at Rudolph's Boston Government Service Center

For context, it may be useful to look at the overall plan of Boston’s Government Center area, which was laid out by I.M. Pei. There are several prominent buildings in the area, which were all built as part of the development of this center. The large rectangular building (near the center of this drawing) is the Boston City Hall (by Kalllmann, McKinnell & Knowles). The large, gently curving building to its left is Center Plaza (built as offices and ground-floor retail) designed by Welton Becket. Rudolph’s Government Service Center follows the perimeter of the triangular site at the map’s upper-left. About equidistant between the City Hall and the Government Service Canter are the two towers (shown as offset rectangles) of the John F. Kennedy Federal Building by Walter Gropius and The Architects Collaborative. Quincy Market, the celebrated food marketplace, is the long, horizontal, dark rectangle at the far right. It was designed by Alexander Parris and built in the early 19th Century.

Here’s a satellite view of the same area as shown in the drawing at the top of this post (and shown at approximately the same scale.) If you look at the drawing above, the entire site for Government Service Center was to be utilized for its building (plus the outdoor plazas, also designed by Rudolph)—and there was to be a tower in the center. In the photo above, one can see that the tower was not built, and the right-hand side of the site is now occupied by a wedge-shaped structure which was constructed later: it’s a municipal courthouse building, designed by another firm. Image courtesy of Google: Imagery ©2019 Google, Imagery

As we mentioned in our last update on this developing story, the State of Massachusetts’ Division of Capital Asset Management & Maintenance has issued a power point deck about the redevelopment proposal. In our last posting, we looked at their first slide: “Hurley Building at a Crossroads” (which was about the current condition and challenges of the building)—and offered our sincere questions and concerns.

Now it’s time to go a bit deeper into the deck, and consider the state’s further assertions and proposals. Let’s look at the next two:

REDEVELOPMENT PROPOSAL

Following each of the slide’s points, we offer responses/questions:

Ground-lease entire Hurley Building site to redevelopment partner, who will lead planning, financing, and construction.

Shouldn’t there be a wider array of input from the beginning, to achieve good, public-spirited design? That would be lost if the development process is walled-off at its beginning—only soliciting public input later, (after the parameters seem to have been set). Without getting public input early it, it can lead to less-than-optimal results for the state and its citizens.

Redevelopment partner will build office space for both private use and state use.

It would be useful to know how the ratio determined?

State to control office space for its own use over long term.

It is important that the definition of “long term” be made explicit. If there’s a termination date to that agreement, then—at that end-date—how are disruptions to be avoided? Conversely: the state already owns the site—so, as long as they are their own tenant, there’s no need to worry about end-dates.

Partnership will be competitively procured through a request for proposals (RFP), request for qualifications (RFQ), or similar

It’s important to keep in mind that the overall proposal requires turning public space and buildings over to private use. Occasionally this can be done as a win-win situation, but it depends on many factors—and one of them is the quality and track-record of the development partner. So a key question is: Will the qualifications examine whether the developer has a real record of tangibly “giving back” (through the quality of what they build/plan)?

Similar to approach used to renovate Saltonstall building 20 years ago.

It would clarify things if we were told by what set of standards that success was judged—and how that was measured, and how far the project went to fulfill that.

Commonwealth will consider both qualitative and quantitative information from potential partners, in order to maximize value for the Commonwealth.

It would be useful to all parties if the above terms could be clarified—particularly the qualitative aspect.

This is the most cost-effective way to meet the state’s downtown office needs while improving the site for all users and the City of Boston generally.

Much is condensed into this one sentence. Implicit are assertions about: cost-effectiveness, state needs, the nature of the improvements, and who the users are. These would each need careful definition and review.

Lets consider the next slide:

EXPECTED BENEFITS

Following each of this slide’s points, we offer our responses/questions:

New, modern office space for state employees for same or less cost than comparable space elsewhere.

Renovation can usually yield modernization as comparable/less cost---if done efficiently. Moreover, renovation is almost always the greener alternative.

Long-term cost stability for both capital and operating budgets.

It would be good to know what this is this being compared to.

Improved public realm across 8-acre block. Increased site utilization and activation.

There’s abundant knowledge, from today’s public space designers, about making plazas and public spaces more alive and used—and many good case-studies of success. Don’t destroy what we have—but, instead, use that knowledge to make these unique spaces more alive to the public.

Economic benefits from large-scale development (jobs, tax revenue, etc.).

What’s often missing from balance-sheet are the costs of over-(“large scale”) development: especially overburdening the already under-pressure transit system and city services. Jobs will also be created through the modernization of the existing building.

NEXT STEPS

We’ll continue to respectfully review the state’s proposals—and raise questions when items need review an clarification.

If you have information or resources to contribute to preserving this important building by Paul Rudolph, please let us know at:

office@paulrudolphheritagefoundation.org

The overall design for the Boston Government Service Center. Although it is the work of a team of archiects, the design leader was Paul Rudolph-and it is truly his conception. This axonometric drawing shows his original full design for the complex—including public plazas in the center and at the three corners. In the middle was to be a tower with a “pinwheel”-shaped plan (in this drawing only the first few floors of it are shown.) © The Paul Rudolph estate, Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

S.O.S: - Save Rudolph's Boston Government Service Center

Niagara Falls' Rudolph Masterpiece—but are we going to lose it?

The Earl. W. Brydges Library, designed by Paul Rudolph—Niagara Falls’ main library, the city’s center of knowledge! The project commenced in Rudolph’s office in 1969, and this view of a portion of it’s lively roofscape was photographed in the mid-1970’s. Image courtesy of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, photograph by G. E. Kidder Smith

CIVIC STANDING

Among the many types of buildings to which Paul Rudolph applied his creative & practical talents—houses (and housing), churches, schools, university buildings, campus planning, exhibit design, office buildings, medical facilities, and laboratories—there’s also the type about which architects feel proudest: their ”civic works.“ Part of that pride emerges from the City Beautiful movement—a philosophy and practice, starting in the late 19th Century, which contended that beautifully-designed cities (and well-designed public buildings within them) could bring forth a better society and promote civic virtue. That movement helped energize city (and state and federal) governments to focus more (and spend more) on their streets, buildings, public facilities (and the civil engineering that undergirded those structures.) It’s worth noting that a building type which played a role in such planning were public libraries.

RUDOLPH IN THE PUBLIC REALM

Rudolph made a strong showing in the civic domain, being given commissions for government and public-use buildings in Boston, New Haven, Goshen, NY, Syracuse, Rockford, IL, Buffalo, Siesta Key, FL, Manhattan, and Bridgeport—as well as for international locations, like Jordan and Saudi Arabia. These projects ranged from city halls, to courts, a stadium, and an embassy. [We’ve even seen a 1995 listing, in the tabulation of projects which Rudolph’s office produced for its own use, for a design of an “office for special counsel”.]

PROMINENT ON THE STREETSCAPE

Not all those projects were built (as with the career of most architects, that’s par for the course)—but enough were constructed that we can see that Rudolph’s skills “scaled” well for significant public undertakings. Among those, the main library he did for the city of Niagara Falls—the Earl W. Brydges Public Library— is remarkable. Here, he literally created a “landmark”: a prominent and sizable structure of unforgettable form—an icon within the cityscape.

The library in 2004, as seen down from within the city of Niagara Falls, NY. The tall, glazed, staggered portions of the roof (which bring light into the reading spaces within the building) are prominent parts of the building—and these strong shapes make the library a landmark within the city. Photograph by Kelvin Dickinson, © The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

LUMINOUS INTERIORS

Equally memorable are the interiors, filled with light from the clerestory windows above (whose staggered emergence from the roof helps give the building its mountain-strength character). The 3-storey space within is exciting—yet serene enough for reading, research, and study.

“It’s so bright and open without being glaring.”

—Jennifer Potter, the library’s director

Rudolph’s section-perspective of the library, looking down its main axis. A series of tall clerestory windows, rising prominently from the roof, bring in natural light. The building rises in three stages, with each floor getting smaller than the one below—reflecting the library’s functional space needs. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

“I think my favorite thing about the building is looking up in the main atrium, where the adult collection is. So stunning. It feels strangely modern despite its age.”

—Library Patron

The library’s atrium-interior, as photographed in 1972. This view allows one to see all three levels, as well as the ceiling openings to the clerestory windows (in the angled roof) which bring natural light into the space. Joseph W. Molitor architectural photographs. Located in Columbia University, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Department of Drawings & Archives

A LANDMARK THREATENED?

The building’s birth had, admittedly, construction problems—ones that caused its architect and builder seeming endless grief. This history is well-told in an article by Mark Byrnes, published by CityLab a few years ago (from which the above quotes.were excerpted.) Ongoing issues continue to concern its users—to the point where the building’s future as the city’s main library is now being threatened.

Is this a case similar to another amazing civic work by Rudolph: his now-disfigured Orange County Government Center? There, a greater recognition of the building’s architectural value and excellence might have—whatever the problems—brought forth the commitment and resources to fix them. We hope that such understanding and support will come forth for the library in Niagara Falls—that it “gets some love”.

INTO THE FUTURE?

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation will be following the fate of Niagara Falls’ Brydges Library (and working to preserve it.) We’ll be bringing you ongoing news of this in the coming months—and if you hear anything about the future of the building, please do let us know!

The entry side of Niagara Falls’Earl. W. Brydges Library, designed by Paul Rudolph. Image courtesy of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, photograph by G. E. Kidder Smith

A SERIOUS THINKER TAKES ON "BRUTALISM"

The exterior of the main hall of the Kyoto International Conference Center in Japan, designed by Sachio Otani. Kate Wagner uses a photo of this building in the introduction to her new series of articles, in which she considers Brutalism and other key issues in architecture. A detail of a photograph by Daderot; photo courtesy of Wikipedia.

Who Doesn’t Just Love McMansion Hell ?

You know it— McMansion Hell, Kate Wagner’s smart, funny, pointed, and insightful blog-website about what’s wrong (and occasionally right) with architecture, urbanism, and the environment. It’s most well-known for her “comedy-oriented takedowns of individual houses”, in which she shows, in her clear-eyed opinion, some of the most egregious “McMansions” and hilariously points out what’s false, ostentatious-without-taste or sense, or just dumb about them.

An sample, from a recent entry on the McMansion Hell blog, of Kate Wagner’s sharp analysis of a “McMansion”. This one is from June 13, 2019, which you can read in-full here.

Hmmmm. Maybe the only people who don’t like McMansion Hell are those who market such pretentious flab. If you aren’t a regular visitor to McMansion Hell, we recommend you do so—it is a constant eye-opener—and if you want a rich education, also explore the site’s archive.

More Than Satirical

Yes, via her sharpshooter aim at flatulent architecture (and its boosters), she does evoke hilarity (tho’ one that has an authentically public-spirited purpose). But it’s really worth underlining that she’s a penetrating and careful (and caring) thinker—one of the most articulate on the scene today. Her writings take on vital issues, and she readily and clearly (with delightful power) points out what’s full of pretension, hypocrisy, obscuring and inflated language, or just muddy thinking.

An Approach to Brutalism—One That’s Needed, NOW

Here at the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, it got our attention when Kate Wagner announced that she was commending a 5-part blog series on Brutalism. That term— “Brutalism”—has been used against Paul Rudolph like a demolition battering ram—and, less frequently, as a term of praise (tho’ sometimes bafflingly, to those outside intricacies of the debate.)

The opening page, image, and paragraph of McMansion Hell’s 5 part series on Brutalism. We’re delighted that she starts off with a image of one of Paul Rudolph’s most fascinating projects: his campus design at UMass Dartmouth.

She explains the need for a thoughtful approach to the phenomenon (and built works) of Brutalism, explaining:

I’ve been a spectator to this debate since I first lurked in the Skyscraper City forums as a high school freshman, ten years ago, when Brutalism itself sparked the interest in architecture that brings me here today. I have, as they say, heard both sides, and when asked to pick one, my response is unsatisfying. Though my personal aesthetic tastes fall on the side of “Brutalism is good,” I think the actual answer is it’s deeply, deeply complicated.

And insightfully adds (and questions):

Brutalism has a special way of inspiring us to ask big and difficult questions about architecture. “Is Brutalism good?” is really a question of “is any kind of architecture good?” - is architecture itself good? And what do we mean by good? Are we talking about mere aesthetic merits? Or is it more whether or not a given work of architecture satisfies the purpose for which it was built? Can architecture be morally good? Is there a right or wrong way to make, or interpret, a building?

She declares the need to approach this topic with the subtlety it deserves—and the urgency it demands::

I have bad news for you: the answers to all of these questions are complicated, nuanced, and unsatisfying. In today’s polemical and deeply divided world of woke and cancelled, nuance has gotten a bad rap, having been frequently misused by those acting in bad faith to create blurred lines in situations where answers to questions of morality are, in reality, crystal clear. This is not my intention here.

Existential questions aside, there are other reasons to write about Brutalism. First, while we’ve been hemming and hawing about it online, we’ve lost priceless examples of the style to either demolition or cannibalistic renovation, including Paul Rudolph’s elegant Orange County Government Center, Bertrand Goldberg’s dynamic Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago, and the iconic Trinity Square, Gateshead complex, famous for the role it played in the movie Get Carter. My hope is that by bringing up the nuances of Brutalism before a broad and diverse audience, other buildings on the chopping block might be spared.

And promises:

This is a series on Brutalism, but Brutalism itself demands a level of inquiry that goes beyond defining a style. Really, this is a series about architecture, and its relationship to the world in which it exists. Architects, as workers, artists, and ideologues, may dream up a building on paper and, with the help of laborers, erect it in the material world, but this is only the first part of the story. The rest is written by us, the people who interact with architecture as shelter; as monetary, cultural, and political capital; as labor; as an art; and, most broadly, as that which makes up the backdrop of our beautiful, complicated human lives.

Yes, this series is going to be an absorbing adventure. Kate Wagner is not only examining Brutalism, but also taking-on some of the most vital questions around architecture—and we look forward to future installments!

The Duel Over Modernism

Paul Rudolph’s Orange County Government Center, prior to its partial demolition. Was it yet another victim of profound misunderstandings about architecture and beauty?

Photo by Daniel Case

THE DEBATE

SETTING UP THE DUEL

Prospect is a monthly British magazine which covers a variety of topics and issues, from national & international news to the arts—and their authors (and the points-of-views expressed) are from across the spectrum. They recently sponsored a debate about the value and effect of Modern architecture—and Brutalist architecture in particular. The article is titled:

The Duel: Has Modern Architecture Ruined Britain?

And subtitled:

Our two contributors go head-to-head on the brutality—or not—of brutalism

And you can read the full article about the debate here.

The “duelists” are intelligent, well-informed, and articulate—and, at the on-line article’s end, there was even an opportunity for readers to vote on who “won.” We thought it would be good to bring this debate to your attention. It’s not long, and is well worth reading—and we do have a few comments on it (which we’ll address at the end).

THE DUELISTS

Barnabas Calder:

Dr. Calder is an architectural historian at the University of Liverpool School of Architecture. He has written books about the history of architecture and about the work of Modern architect Denys Lasdun, as well as many papers, chapters, and reports on architecture, design, and urbanism. In 2016 he published his Modernist manifesto, “Raw Concrete: A Field Guide to British Brutalism.” In a recent article in Garage magazine, he remarks “People used to laugh out loud when I told them I was studying 1960s concrete buildings. Part of the change is no doubt just passing time. As with haircuts, clothes, and glasses, tastes change and the previous fashion goes violently out of style for a while, then gets gleefully rediscovered by younger people a bit later.” And in an article in Wallpaper, he goes on to says of Brutalism, “It’s still both misunderstood and wildly underestimated”… “the period produced masterpieces equal to anything else produced in architecture.”

James Stevens Curl:

Dr. Curl is an architectural historian, architect, and prolific author. He is Professor at Ulster University’s School of Architecture and Design, and Professor Emeritus at de Montfort University, and was a visiting fellow at Peterhouse, Cambridge. He was awarded the President’s Medal of the British Academy, and is a member of the distinguished Art Workers’ Guild. Among his many books are: “English Architecture: An Illustrated Glossary”; “Classical Architecture: An Introduction to Its Vocabulary and Essentials”; and the “Oxford Dictionary of Architecture”. Most recently, Oxford University Press published his in-depth study of Modernism: “Making Dystopia: “The Strange Rise and Survival of Architectural Barbarism”.

Book cover images: Amazon

POINTS (AND COUNTERPOINTS) FROM THE DEBATE

The debate was frank, and the speakers expressed themselves forcefully. Here are excerpts from some points each made—direct quotations from the two “duelists”:

Points that Modern architecture is ruining Britain

(Quotes from Dr. Curl):

Visitors to these islands who have eyes to see will observe that there is hardly a town or city that has not had its streets—and skyline—wrecked by insensitive, crude, post-1945 additions which ignore established geometries, urban grain, scale, materials, and emphases.

Such structures were designed by persons indoctrinated in schools of architecture… Harmony with what already exists has never been a consideration for them … [They have] done everything possible to create buildings incompatible with anything that came before. It seems that the ability to destroy a townscape or a skyline was the only way they have been able to make their marks. Can anyone point to a town in Britain that has been improved aesthetically by modern buildings?

How has this catastrophe been allowed to happen? A series of totalitarian doctrinaires reduced the infinitely adaptable languages of real architecture to an impoverished vocabulary of monosyllabic grunts. Those individuals rejected the past so that everyone had to start from scratch, reinventing the wheel and confining their design clichés to a few banalities. Today … modern architecture is dominated by so-called “stars,” and becomes more bizarre, egotistical, unsettling, and expensive, ignoring contexts and proving stratospherically remote from the aspirations and needs of ordinary humanity.

You use the old chestnut that because some new buildings were initially perceived as “shocking,” but accepted later, this applies equally to modernist ones. Studies refute this. Modernist buildings seriously degrade the environment by generating hostile responses in humans and damaging their health. I suggest you peep at Robert Gifford’s “The Consequences of Living in High-Rise Buildings” in Architectural Science Review….

Much modernist design denies gravity and sets out to create unease. You love concrete, with its black, weeping stains, its tendency to crack, its ability only to deteriorate and never age gracefully. Your bizarre judgments ignore obvious signs that reinforced concrete is not the answer to everything.

You cannot see (or admit) that the harmoniousness of our townscapes has suffered dreadfully since the universal embrace of modernism so there is nothing I can do to help you or other Brutalist enthusiasts. Your myopia explains why you fail to notice that members of the “British Brutalist Appreciation Society” are less numerous than are paying members of the Victorian Society.

You employ a cheap debating-point: you assume that anyone who criticizes inhuman non-architecture wants a return to Greco-Roman Classicism, which is untrue. … I argue for environments fit for ordinary human beings, which embrace elements that are an integral part of what remains of our once-rich cultural heritage. I am also fully aware of the massive propaganda and bullying in architectural “schools” that brainwash our young architects to embrace what is inhuman, repellent, and ugly.

Points that Modern architecture isn’t ruining Britain

(Quotes from Dr. Calder):

You make sweeping criticisms against the architecture of recent decades—a lot of styles and ideas have come and gone since 1945. The term “modern” covers a lot of ground. But the truth is that all of your allegations were [once] levelled with equal justice at Victorian buildings.

Today’s skyscrapers also change the skyline, as you say. But so did medieval castles and churches, or Victorian town halls and stations. Like the high buildings of earlier centuries, tall office blocks map where the money and power lie. The City of London is aggressively commercial—as it always has been. The developers of the 20th and 21st centuries are no more ruthless than those of the 17th to 19th centuries. The great post-1945 regenerations, by contrast, aimed to improve the housing of ordinary people.

Appreciating any style requires an open mind; any language sounds like “grunts” until you listen. Architects trained since 1945 have received better history teaching than any earlier generation; the Barbican is the proud descendant of the great Victorian projects. It recasts London’s Georgian crescents and squares into exhilarating and livable new forms using the unparalleled structural capabilities of concrete. Had Vanbrugh, Soane or Scott worked in the 1960s, they would have been proud to produce anything as heart-liftingly sublime.

By what definition has Britain been “ruined” since 1945? The high tide of modernism in post-war Britain coincided with a steep and sustained rise in the population’s health, education and prosperity.

However, much though I admire the best buildings of the period, I would not ascribe this improvement to architectural aesthetics. I do not share your peculiar faith in the power of architectural style to ruin lives.

Can anyone truly believe that crime and suffering in Britain’s poorest areas is caused by an absence of classical columns, rather than working-class unemployment from de-industrialization? Does anyone really think that if the Barbican had been brick, not concrete, it would not have been caught up in the industrial action of the 1970s? Anyone who finds concrete “black” with dirt should compare it with the coal-black sandstones of Glasgow under Victorian soot.

As to whether modernism has the potential to pass into a period of new public appreciation, as Victorian architecture did in the 1960s-70s, its stock has been rising fast for at least the past decade.

Your angry dismissal of several decades of world architecture as an evil conspiracy is implausible. Your “overwhelming evidence” of the psychological damage done by the architecture you happen to dislike largely consists of methodologically problematic, politicized writings.

Personally, I like architecture best when it’s as sublimely overwhelming as Michelangelo, Hawksmoor or Ernö Goldfinger. However, modernism can also be pretty and harmonious, …. It can be courteously contextual street architecture....

Modern architecture can be symmetrically dignified like Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute, or thrillingly asymmetrical like Lasdun’s Royal College of Physicians. Recent architecture can be as curvaceous and hallucinatory as the Italian baroque (Paul Rudolph in Boston, MA, or Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim exterior) or as tightly-controlled and rhythmical as the German classicist Schinkel (anything by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe). Interiors can be cozy like Alvar Aalto’s houses, or grandly formal like Kahn’s Dhaka parliament. Perhaps the thing modernist buildings’ detractors find hardest to see is that they can be beautifully crafted, like the meticulous concrete-work of the National Theatre, carefully poured into hand-made wooden moulds.

I urge readers to enjoy what is good about any architecture. Frothing with fury at the sight of newer buildings is an unproductive use of emotional energy and serves only to impoverish the rich experience of our varied cityscapes.

WHAT’S FAIR IS FAIR

We’ve tried, in the excerpts above, to give representative and approximately equal space to each speaker (as well as their biographies).

And now—offered in that same spirit of fairness—we have some comments:

If you’re iffy on the architectural value and long-term worth of concrete/Brutalist architecture, Dr. Calder’s book is “a way in” to understanding and—just as important—appreciating such designs as being true works of architectural merit (and art), as well as places that can nourish the human spirit. In his debate points, he exhorts us to stay open—and his book is the sort of design-meditation which helps us to look for poetry and humanity where we might not think it can be found.

On-the-other-hand, Dr. Curl’s recent book is a shocker. If you are on his “side” (and we would do well to remember Alex Comfort’s wisdom about sides: “… the flags are phony anyhow.”) then in Curl’s book will find confirmation of your inclinations, backed by in-depth research about the points he makes above. But even if you are opposed, you will find eye-opening historical information on the origins and sub-texts of Modernism.

It does no one any good to deny the faults and problems of Modern architecture—and this is particularly true when it comes to city planning (as distinct from individual buildings). While it can create some marvelous perspective drawings, the more than half-a-century of the “tower in the park” model of Le Corbusier shows how preponderantly unsuccessful it is—and sometimes a disaster. This is usually and especially so when the tenants (the “demographics”) of a project are not of a high-enough income level supply sufficent funds to building management, to allow the staff to maintain & manicure their buildings and districts.

But it is really unfair to impugn the motives of Modern designer and planners. Many were utterly sincere—sincerely idealistic!—that new approaches could yield better lives.

People today have no idea of the devastatingly inhuman conditions of pre-WWII cities, particularly in the working-class sections (and a reading of Jacob Riis’ book is illuminating on what citizens really had to live in and with.) So consider the case of Ludwig Hilberseimer: a teacher at the Bauhaus (who, after emigrating to the US, ended up working for Mies and teaching at IIT). Visions of rebuilt cities and mass-habitations, like those offered by Hilberseimer, may look weirdly dystopian—But: they were sincerely-offered proposals, trying to give ground-down citizens places that were clean, with light and air; and access to electricity, plumbing, and heating (services which we’d consider “basic” today, but which most city dwellers back then could only dream of). Hilberseimer’s vision, tho’ repugnantly reductive to our eyes today, was part of a sincere program to replace existing urban hells.

One of Ludwig Hilberseimer’s visions for the a reformed, rebuilt, efficient city. Image: Drawing by Hilberseimer, from 1924.

It’s foolish to deny the beauty of some Modern works. We’re a particular fan of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye:

The Villa Savoye, in Poissy, on he outskirts of Paris. Design work was begun by Le Corbusier in 1928, and the building was completed in 1931. Source: Wikipedia

But, admittedly, that iconic house is an “object” in the landscape—and, yes, almost anything can look good in such an isolated sculpture-ish context. It’s much harder to do a successful building in the city, and even harder to create good urban spaces. Rudolph was aware of this, and called for urban vitality and variety, saying:

“We desperately need to relearn the art of disposing our buildings to create different kinds of space: the quiet, enclosed, isolated, shaded space; the hustling, bustling space, pungent with vitality; the paved, dignified, vast, sumptuous, even awe-inspiring space; the mysterious space; the transition space which defines, separates, and yet joins juxtaposed spaces of contrasting character. We need sequences of space which arouse one’s curiosity, give a sense of anticipation, which beckon and impel us to rush forward to find that releasing space which dominates, which acts as a climax and magnet, and gives direction. Most important of all, we need those outer spaces which encourage social interaction.”

We also have to be honest about acknowledging the problems of concrete construction—particularly exposed concrete. Curl and company are not “seeing things” when they report streaking, grayness, and an overall depressingly dingy look. But that is not true of all concrete construction—as many works of Rudolph and others show over-and-over. Moreover, the techniques to care for and repair concrete buildings are getting better-and-better.

The challenge is, when concrete is used, to use it with the mastery of those who make it luminous. There are ways to do that—but it takes knowledge (both in the drafting room and on the construction site), and it’s hard to transcend rock-bottom budgets.

When concrete is done well—and Rudolph’s Temple Street Garage in Boston comes to mind as a superb example—it is sculptural, moving, captures the light in wonderful ways, and is even sensuously textured:

Paul Rudolph’s Temple Street Garage, Boston. Photo: NCSU Library – Design Library Image Collection

Or it can be mindfully serene, as in much of Ando’s work:

Ando’s Benesse House, Japan. Photo: courtesy of Tadao Ando

Finally, we’ll quote from one of Rudolph’s former students, Robert A. M. Stern. When considering such seeming oppositions (as in this “duel”), he said:

“It is not a matter of Modern Architecture or Classical Architecture—but rather of Good Architecture and Bad Architecture!”

Do we have to condemn a whole architectural style or approach? The world, including its architectural history, is complex, messy, big—and terribly hard to classify or comprehensively judge. Who could?

Better that we should develop and sharpen our ability to practice and make caring decisions—that’s the way to better architecture.

Paul Rudolph’s Pencils and Pens. Image: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

CONCRETE HEROES: SAVING THE MONUMENTS OF MODERN ARCHITECTURE

A review of:

CONCRETE: CASE STUDIES IN CONSERVATION PRACTICE

Edited by Catherine Croft and Susan Macdonald with Gail Ostergren

Conserving Modern Heritage series of the The Getty Conservation Institute

www.getty.edu/publications

These images, from “Concrete: Case Studies in Conservation Practice,” are from the chapter about concrete restoration at Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation in Marseille.

Buildings are like human bodies: over time, things happen to them—generally not good things….Even when Modern architects had the best intentions, and relied on what they thought was forward-looking and scientifically derived construction methods, the “bodies” of Modern buildings are showing their age. Some repairs are easier than others: one can re-plaster or re-apply stucco without too much trouble. But some are head-scratchers, as when, during renovation, one finds that the original architect used a product that is no longer available. That happened when renovating a famous mid-century Modern house: a plastic corrugated panel (of a type popular in that era) was not made any more—leading to an expensive custom order. But among all the materials that present themselves for repair, concrete—especially exposed concrete as used in some of Modernism’s most iconic works—is among the most difficult to work with.

We’re all familiar with classic views of Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation at Marseille—truly an icon of Modern architecture—but what of the reality when moisture has seeped below the surface and corroded the reinforcing, and parts of the surface have flaked off? Can it be repaired? [And by “repair”, we don’t just mean excising and replacing broken or decayed areas, but rather making the repair blend-in as much as possible, so that it does not look like a carelessly done patch. ]

Moreover, concrete buildings have their own special issues. When moisture reaches reinforcing, it not only leads to spalling (as the rusting steel expands), but also possibly undermines the structure itself—with serious consequences for the building’s integrity. Dirt from the atmosphere and streaks from flowing water adhere to concrete’s subtly fissured surfaces… Well, there’s no need to go on, as the indictments against aging concrete are already part of the pro-and-anti Modern architecture discourse—and particularly when discussing works that have been characterized as “Brutalist” [A term, by-the-way, which we dispute—but that’s another discussion.] Since a significant portion of Paul Rudolph’s oeuvre used exposed concrete—beautifully and artistically, we contend—we are naturally concerned about repair issues and techniques.

“Concrete: Case Studies in Conservation Practice” is a fascinating new book that offers hope and tangibly useful information on the repair of concrete architecture. They do it via case studies—and oh what “cases” they show: some of the most famous buildings of the Modern era!

Among their 14 case studies are:

Unité d’habitation by Le Corbusier

Brion Cemetery by Carlo Scarpa

New York Hall of Science by Harrison and Abramovitz

Morse and Ezra Stiles Colleges, Yale, by Eero Saarinen

Church of Saint Francis of Assisi, Pampulha by Oscar Niemeyer

“Untitled,” an artwork by Donald Judd

Each had its own problems, and the many authors (34 contributors in all) show the unique issues of the buildings, the solutions proposed and executed—and, finally, the superb, fresh results of their ministrations.

Did we say that the book is beautiful? One doesn’t usually expect technically-oriented studies to be visually attractive but this volume shows it can be done. The writers and editors (with Getty’s book designer for this project, Jeffrey Cohen) have assembled a wealth of good photographs (many in color), intriguing drawings (some vintage, and may newly created), and vivid diagrams—and put them together in a way that is inviting. Each case/chapter’s text clearly describes the various teams’ approaches to their building, their careful investigations, their considerations in choosing which techniques were to be used, and the consequences. Yet, while fully informative, the amount of detail is not overloaded, and can be readily digested by the interested reader. We wish more architecture/construction-science books were so appealingly and richly communicative.

There is nothing as convincing as “before and after.” This book shows a multiplicity of projects—differing in their problems, sizes, scales, locations, and building types. It makes abundantly clear that, however grim and despair-inducing concrete repair problems can be, there are effective, creative, rigorous techniques for resolving them. Bravo to the authors and editors of this fine book—and to the Getty Conservation Institute for bringing it forth. We look forward to future volumes in their Conserving Modern Heritage series.

Rudolph's Shoreline Apartments in Buffalo - an Artist Responds - Artistically!

“Disposable: Shoreline Apartment Complex Unit” Plastic canvas, acrylic yarn, tissue box, 8 X 16.5 X 21 inches, 2016.

An artwork by Buffalo-born & based, fiber artist Kurt Treeby. This is his depiction of Paul Rudolph’s Shoreline Apartments in Buffalo. It is part of a set of works by Treeby, the “Disposable” series, involving—in the artists recounting—“thousands of precise stitches, all sewn by hand…”

Photo: www.kurttreeby.com

SHORELINE APARTMENTS IN BUFFALO

Shoreline Apartments is a fascinating complex of residences on Niagara Street in Buffalo, NY, completed in 1974 to the designs of Paul Rudolph. To say that it “is” is a bit problematic, because the entire set of residences is slated for demolition - and, as of this writing, about half of the complex still exists (but how long that extant portion will remain is unknown.)

“Rudolph’s original scheme, composed of monumental, terraced, prefabricated housing structures, provided an ambitious alternative to high-rise dwelling that was meant to recall the complexity and intimacy of old European settlements.” – Nick Miller, in The Architect’s Newspaper

Here’s a good, concise background on the project, as reported by Nick Miller in The Architect’s Newspaper (November 5, 2013):

[Arthur] Drexler exhibited Rudolph’s original, much more dramatic scheme for Buffalo’s Shoreline Apartments alongside pending projects by Philip Johnson and Kevin Roche in an exhibition entitled Work in Progress. The projects on display were compiled to represent a commitment “to the idea that architecture, besides being technology, sociology and moral philosophy, must finally produce works of art.”

Completed in 1972, the 142-unit low-income housing development was featured in both the September 1972 issue of Architectural Record as well as the 1970 exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Like many of their contemporaries, the inventive, complex forms and admirable social aspirations of the development have been overshadowed by disrepair, crime, and startling vacancy rates (30 percent in 2006 according to Buffalo Rising).

The Shoreline Apartments that stand today represent a scaled down version of the original plan. Featuring shed roofs, ribbed concrete exteriors, projecting balconies and enclosed gardens, the project combined Rudolph’s spatial radicalism with experiments in human-scaled, low-rise, high-density housing developments. The project’s weaving, snake-like site plan was meant to create active communal green spaces, but, like those of most if its contemporaries, the spaces went unused, fracturing the fabric of Buffalo.

Here’s an image of a portion of the Shoreline complex, as built:

The Shorelines Apartments in 1975, shortly after opening. The large Art Deco skyscraper, at the rear-right, is Buffalo’s City Hall.

Image: Courtesy of EPA/Library of Congress

THE ARTIST: KURT TREEBY

Mr. Treeby, a fiber artist that’s a native of Buffalo (and who is based here), does fascinating work, and—on his website—you can find his own text on his career, from which we quote:

Kurt Treeby first studied art at the College of Art and Design at Alfred University. While at Alfred he studied painting, drawing, and art history. After receiving his MFA from Syracuse University Treeby develped a conceptual-based approach to art making that continues to develop as he works with a wide range of fiber and textile processes. His work comments of the production and reception of art, as well as the role art plays in our collective memories. He focuses on iconic imagery and the connection between so-called "high" and "low" art forms. Treeby has exhibited his work on a national and international level. He teaches studio art and art appreciation at the College at Brockport, State University of New York, and Erie Community College.

KURT TREEBY’S “DISPOSABLE” SERIES

The artist has done a series of artworks, each of which is a significant building (or complex of buildings) that has been demolished—or, like Shoreline, is on the way to being demolished. Among the building’s he’s focused on are: The Larkin Building (by Frank Lloyd Wright), BEST Products Showrooms (by SITE), the Niagara Falls Wintergarden (by Cesar Pelli), and various other structures. The one he did, of a portion of the Shoreline, captures the Paul Rudolph’s design very nicely!

Here are some excerpts from Mr. Treeby’s beautiful and sensitive artistic statement on his work—and this series in particular:

Every city includes a variety of structures including historical landmarks, industrial factories, and utilitarian homes. My work examines the architectural ecosystem of production, consumption, and destruction embedded into the social, economic, and physical landscape of cities, reimagining a future apart from their industrial or commercial past.

Focusing on iconic structures, I faithfully replicate architectural and structural details from an alchemy of historical records and collective memory. I recreate these buildings in plastic canvas and craft-store yarn, amplifying the tension between fine art and craft. The final sculptures function as the visual embodiment of the restoration process, as historical records, and as personal memories; all imperfect and incomplete.

I use the medium of plastic canvas because it is rooted in domestic crafts. Traditionally, the medium is used to construct decorative covers resembling quaint cottages or holiday-themed houses for disposable items like tissues and paper napkins. Unlike the fantastical commercial patterns, my sculptures are often larger, replicating complex buildings that have been demolished or significantly altered over time. Because I cannot always experience the original structures, I combine archival records and satellite imagery to help me understand the building’s original site.

The hours spent on each piece are a meditation and a reflection on loss. Engaging in this meticulous process is my way of paying tribute to the original architects. My imperfect buildings act a stand in for the original, and as monuments to memory itself.

We urge you to visit Kurt Treeby’s website, and explore his movingly intriguing work for yourself: http://kurttreeby.com

Paul Rudolph's Futuristic Vision: The Galaxon

Rendering of Paul Rudolph’s ‘Galaxon’. Image: Shimahara Illustration

VISIONS OF THE FUTURE

There are not many phrases more evocative than “THE FUTURE”. Whether in joyous expectation or fear (of a mixture of both), imagining, predicting, envisioning, and forecasting The Future has been one of humanity’s longest obsessions - and indeed, many religious and social practices, going back to the most ancient of times, are concerned with prognostication.

New York World’s Fair Button from the General Motors Futurama Exhibit. Image: www.tedhake.com

But, beyond the products of imagination (literature, art, and film), where can one actually go to get a tangible touch, a taste of the future? Not a virtual reality version, but rather an experience where one can actually wander around samples of a futurific world? The answer is—or rather, was—world’s fairs.

WORLD’S FAIRS — THE GEOGRAPHY OF WONDER

Humans also have a taste for novelty, adventure, the exotic, and news from beyond our borders (and products, material and cultural.) One phenomenon brings such appetites together with our fascination with the future: World’s Fairs.

World’s fairs were international events, taking place in intervals varying from several years to several decades. A city—like Paris, London, Osaka, New York, Seville, Rome - would be selected, and countries, states, companies, and trade organizations (and even religions) would erect pavilions - each of which would show the sponsor’s self-image and aspirations to the fair’s visitors (coming, often from all-over-the-world, during the fair’s few months duration.)

For countries, their industrial, consumer, and agricultural products would be featured, along with something of the nation’s culture—and generally there would be a lauding of the leaders, government, and “way of life”.

Companies, too, would extol their accomplishments, productive might, and the quality of their products. Most interestingly, they would often present displays about the forefront - The Future - of technology in their field. Sometimes such demonstrations were startlingly dramatic, but sometimes amusingly humanizing—like the talking (and joking) robot, Elektro (with his robot dog, Sparko), who were featured in the Westinghouse pavilion of the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair.

The architecture of the pavilions in world’s fairs have been particularly powerful evokers of “tomorrow.” Examples range from the jaw-droppingly giant (for that time) open space (377 feet x 1378 feet, and open to a height of 13 storeys) of the Galerie des machines in the 1889 Paris fair to the gargantuan geodesic dome of the US pavilion in Montreal’s Expo 67. Each building competed for the visitor’s attention—and, through striking shapes, unusual construction systems, and the manipulation of light (natural and artificial), often created dream-like, fantasy, forward-looking/futuristic icons. Sometimes a whole landscape would be populated by these odd, wonderful, future-dreamy buildings—like this view from Expo 67:

Photo: Laurent Bélanger from wikipedia

One of the most famous pavilions of the 1939-1940 New Fair was the “Futurama” exhibit created by Norman Bel Geddes for General Motors: using architecture, and giant, detailed, moving, and carefully lit models, it showed kinetic, luminous visions of tomorrow, beguiling visitors with an image of a motorized utopia. Upon leaving, attendees were given a button that read “I Have Seen The Future”—and no they doubt felt they had.

Even at the distance of decades, the images created by Bel Geddes and his team—and the future-oriented displays and architecture of the fair’s other pavilions—continue to fascinate, and evoke that “If only…” feeling. The great author William Gibson wrote of the ongoing seductiveness of such visions in his short story, “The Gernsback Continuum.”

NEW YORK AND THE FUTURE—AGAIN!

The New York World’s Fair, spoken of above - considered to be one of the greatest fairs of all - took place in 1939 and 1940, just before World War Two. But well after that war - in the midst of the 60’s, one of the USA’s most economically & militarily strong (and socially vibrant) periods - a second world’s fair was held in New York City.

Photo: Anthony Conti; scanned and published by PLCjr

That fair—the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair—was planned on the same pattern as the previous one: countries, companies, and groups each showing themselves off—only this time, with updated images of the future. For better-or-worse, the world had moved from planes to jets, from vacuum tubes to transistors, and from hydro to atomic power. The Future had new horizons—and that future was: Outer Space.

EVERY FAIR NEEDS A SYMBOL

Almost all world’s fairs have had a central building or structure—that serves to symbolize the fair. It is used both to distill the message of the fair, as well as to create an icon around which communication and marketing can be done (as well as being suitable for souvenirs!)

For the 1939 New York World’s Fair, that symbol had been the Trylon and Perisphere: these were huge platonic forms - a gigantic sphere and a spiky, towering, elongated tetrahedron (designed by Harrison and Fouilhoux). They were large enough for visitors to enter, and there was an exhibit inside about the city of the future (designed by Henry Dreyfuss).

Trylon & Perisphere Monuments of 1939 World's Fair in Flushing Meadows Linen Postcard. Photo: Michael Perlman

But for New York’s 1964-1965 fair, a new symbol would be needed. Here’s what Robert Moses - the fair’s boss - said about the search for a symbolic structure:

“We looked high and low for a challenging symbol for the New York World's Fair of 1964 and 1965. It had to be of the space age; it had to reflect the interdependence of man on the planet Earth, and it had to emphasize man's achievements and aspirations. … and built to remain as a permanent feature of the park, reminding succeeding generations of a pageant of surpassing interest and significance.”

A LOFTY VISION - IN CONCRETE

Concrete may be hard and heavy—but it can be manipulated make soaring structures of deft grace and even visual nimbleness. Nor does the concrete industry want to be thought of as stodgy, as they are always showing that they are moving ahead with forward-looking research and engineering—indeed, the American Concrete Institute once produced a set of research findings and projections on the possibility of using their material in a non-terrestrial environment, a book called “Lunar Concrete”!

The Portland Cement Association is, since 1916 “ the premier policy, research, education, and market intelligence organization serving America’s cement manufacturers. … PCA promotes safety, sustainability, and innovation in all aspects of construction, fosters continuous improvement in cement manufacturing and distribution, and generally promotes economic growth and sound infrastructure investment.”

Like other trade associations and companies, the Portland Cement Association wanted to be represented at the fair—and in a very forward-looking way. So they put forward a design for the fair’s central, symbolic structure—one that would embody a feeling of future-oriented optimism (and, of course, use portland cement!)—and they hired Paul Rudolph to design it.

THE GALAXON

Paul Rudolph came up with one of his most daring designs—and, given that Rudolph was one of the world’s most adventurous architects, that’s saying a lot.

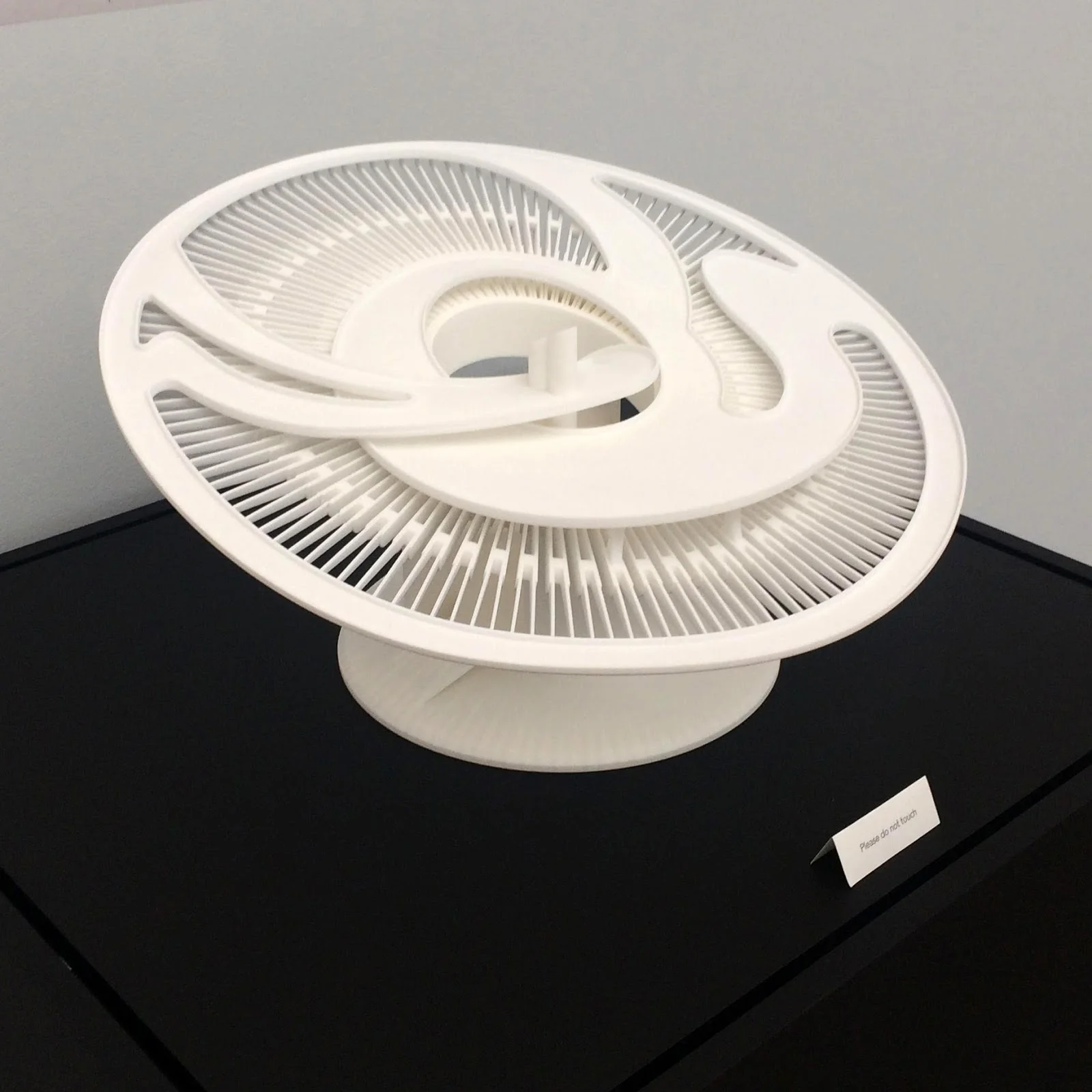

His design was christened “The Galaxon”, and Architectural Record magazine reported:

“The Galaxon, a concrete ‘space park’ designed by Paul Rudolph, head of the Department of Architecture at Yale University, has been announced by the Portland Cement Association as ‘a proposed project’ for the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Its cost is estimated at $4 million.

Commissioned by the P.C.A. as ‘a dramatic and imaginative design in concrete,’ the Galaxon consists of a giant, saucer-shaped platform tilted at an 18-degree angle to the earth and held high above it by two curved walls rising from a circular lagoon. The gleaming 300-foot diameter disc of reinforced concrete would hover in the air like some huge space ship. Visitors would be lifted to the center of the ‘saucer’ by escalators and elevators inside the curved supporting walls. From the central ring they would walk outward over curved ramps to a constantly moving sidewalk on the disc’s outside perimeter. The sidewalk would rise and fall from the 160-foot high apex of the inclined disc, to a low point approximately 70-feet above the ground.

A stage is projected from one of its two supporting walls and a restaurant, planetary viewing station and other educational or recreational features could be located at points along its top surface to make it an entertainment center. The Galaxon was among several designs displayed at an exhibition in New York of the use of concrete in so-called ‘visionary’ architecture.”

- Architectural Record, July 1961

Rudolph did not disappoint—and he created drawings and a model to convey his striking design. The drawings themselves are impressive, with the main one stretching to nearly 20 feet long.

Photo of Rudolph’s presentation model. Image: http://www.nywf64.com

Drawing of night view (with spotlights). Image: "Remembering the Future," "Something for Everyone: Robert Moses and the Fair" by Marc H. Miller, published to accompany the 1989 Queens Museum exhibition "Remembering the Future: The New York World's Fair from 1939 to 1964."

A VISION SPURNED

The real power (to select the central, symbolic structure) rested with Moses - the famous (or, to some, infamous) Robert Moses, who’d built so many bridges, roads, and other facilities, all over the tri-state area. Of searching for an iconic central structure for the fair, he said:

“We were deluged with theme symbols - mostly abstract, aspirational, spiral, uplifting, flashing, or burning with a hard and gemlike flame, whose resemblance to anything living or dead was purely coincidental.”

Among the several many designs that Moses rejected was the Galaxon.

And so another structure was chosen, the Unisphere (made from a rather different material: stainless steel - and sponsored by a major manufacturer: US Steel). The Unisphere—still in place after all these years—admittedly has some uplifting visual power, and does still speak to the goal of a unified world.

But it’s not the forward-looking, FUTURE-evoking, space-expansive, upward-aspiring GALAXON.

Fortunately, we have Rudolph’s beautifully drawn visions to sustain our dreams.

PUBLICATIONS, ARCHIVE, AND EXHIBITION

When the Galaxon was originally proposed, it got some press—and it has since also appeared or been mentioned in books on Rudolph, and been on-exhibit.

Paul Rudolph was known for his virtuoso presentation drawings (especially perspectives and sections), and Paul Rudolph: Drawings is a beautiful, large book of them. It was edited by Yukio Futagawa, and published by A.D.A Edita Tokyo Co., Ltd. In 1972. The book includes a well-reproduced perspective view and a section of the Galaxon.

The preponderance of Paul Rudolph’s architectural drawings (well over 300,000 documents!) are in the Library of Congress. The collection includes several fascinating drawings of the Galaxon, which have been scanned and can be seen on-line.

Paul Rudolph’s original rendering. Image: Library of Congress

From the Library of Congress, impressively large, full-size reproductions of Paul Rudolph’s Galaxon drawing were made, which were very prominently displayed in the exhibit, Never Built New York (which was on-view at the Queens Museum from 2017-2018.) While the Galaxon didn’t make it into the exhibit’s catalog (the curators discovered it after the book had gone to press), the catalog is still well worth obtaining, as it is an exceptionally rich collection of visionary proposals for New York City - and it does include other fascinating projects designed by Paul Rudolph.

BRUTMOBILE!

Wolf Vostell, Concrete Traffic, 1970. Campus Art Collection, The University of Chicago. Photo by Michael Tropea. Art © The Wolf Vostell Estate.

Wolf Vostell (1932-1998) might not be a readily-recognized name today, but - primarily from the 60’s -to- the 80’s - he was known as one of the world’s most creatively provocative artists. He often made stimulating & challenging visual statements by incorporating the products of industrial civilization - cars, motorcycles, planes, and [especially] televisions - into his work, and he’s reputedly the first artist in history to integrate a television set into a work of art.

Even if less known today, Vostell might be familiar to the generation of architects educated in the 1970’s, as he was co-author of the 1971 book Fantastic Architecture - a wonder-filled little compendium of artist-generated projects with architectonic flavor.

The simple-minded think that Brutalism is just about concrete - but we know that’s not even close to accurate. Even so, it is often-enough identified with concrete - and that’s where the intersection with Vostell comes in. The man had an intense relationship with both cars and concrete—and in a number of his works, he encased whole automobiles in the material.

One such example is his 1970 artwork, “Concrete Traffic”, now located in a garage in Chicago: it is a 1957 Cadillac, to be precise, which is entombed in 15 cubic yards of gray loveliness!

It’s an extraordinary sight - Brutalism that looks like it’s about to speed off! - and additional views (and more) can be seen here.

A rear view of Vostell’s concrete car. Photo by Michael Tropea.