The Earl. W. Brydges Library, designed by Paul Rudolph—Niagara Falls’ main library, the city’s center of knowledge! The project commenced in Rudolph’s office in 1969, and this view of a portion of it’s lively roofscape was photographed in the mid-1970’s. Image courtesy of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, photograph by G. E. Kidder Smith

CIVIC STANDING

Among the many types of buildings to which Paul Rudolph applied his creative & practical talents—houses (and housing), churches, schools, university buildings, campus planning, exhibit design, office buildings, medical facilities, and laboratories—there’s also the type about which architects feel proudest: their ”civic works.“ Part of that pride emerges from the City Beautiful movement—a philosophy and practice, starting in the late 19th Century, which contended that beautifully-designed cities (and well-designed public buildings within them) could bring forth a better society and promote civic virtue. That movement helped energize city (and state and federal) governments to focus more (and spend more) on their streets, buildings, public facilities (and the civil engineering that undergirded those structures.) It’s worth noting that a building type which played a role in such planning were public libraries.

RUDOLPH IN THE PUBLIC REALM

Rudolph made a strong showing in the civic domain, being given commissions for government and public-use buildings in Boston, New Haven, Goshen, NY, Syracuse, Rockford, IL, Buffalo, Siesta Key, FL, Manhattan, and Bridgeport—as well as for international locations, like Jordan and Saudi Arabia. These projects ranged from city halls, to courts, a stadium, and an embassy. [We’ve even seen a 1995 listing, in the tabulation of projects which Rudolph’s office produced for its own use, for a design of an “office for special counsel”.]

PROMINENT ON THE STREETSCAPE

Not all those projects were built (as with the career of most architects, that’s par for the course)—but enough were constructed that we can see that Rudolph’s skills “scaled” well for significant public undertakings. Among those, the main library he did for the city of Niagara Falls—the Earl W. Brydges Public Library— is remarkable. Here, he literally created a “landmark”: a prominent and sizable structure of unforgettable form—an icon within the cityscape.

The library in 2004, as seen down from within the city of Niagara Falls, NY. The tall, glazed, staggered portions of the roof (which bring light into the reading spaces within the building) are prominent parts of the building—and these strong shapes make the library a landmark within the city. Photograph by Kelvin Dickinson, © The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

LUMINOUS INTERIORS

Equally memorable are the interiors, filled with light from the clerestory windows above (whose staggered emergence from the roof helps give the building its mountain-strength character). The 3-storey space within is exciting—yet serene enough for reading, research, and study.

“It’s so bright and open without being glaring.”

—Jennifer Potter, the library’s director

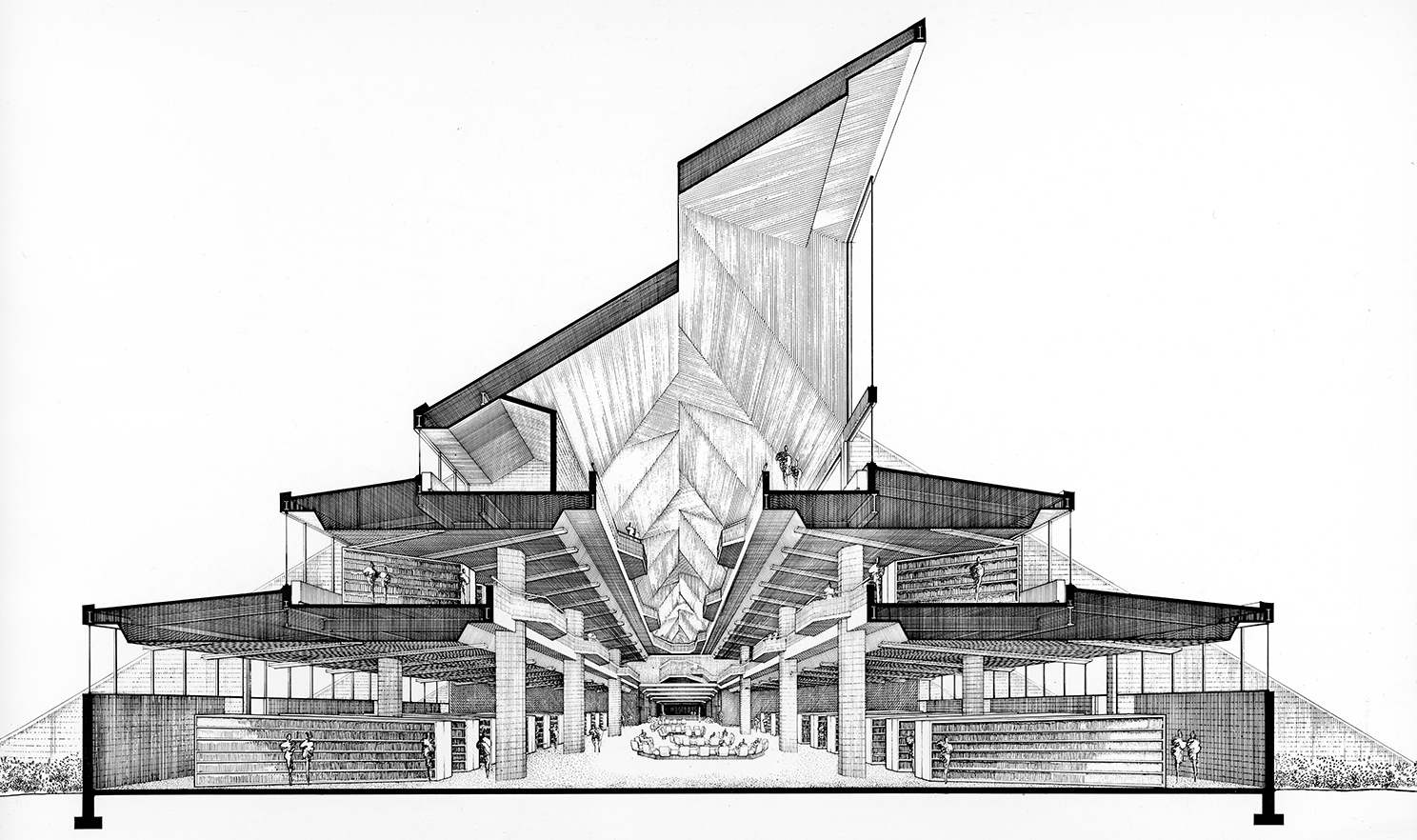

Rudolph’s section-perspective of the library, looking down its main axis. A series of tall clerestory windows, rising prominently from the roof, bring in natural light. The building rises in three stages, with each floor getting smaller than the one below—reflecting the library’s functional space needs. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

“I think my favorite thing about the building is looking up in the main atrium, where the adult collection is. So stunning. It feels strangely modern despite its age.”

—Library Patron

The library’s atrium-interior, as photographed in 1972. This view allows one to see all three levels, as well as the ceiling openings to the clerestory windows (in the angled roof) which bring natural light into the space. Joseph W. Molitor architectural photographs. Located in Columbia University, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Department of Drawings & Archives

A LANDMARK THREATENED?

The building’s birth had, admittedly, construction problems—ones that caused its architect and builder seeming endless grief. This history is well-told in an article by Mark Byrnes, published by CityLab a few years ago (from which the above quotes.were excerpted.) Ongoing issues continue to concern its users—to the point where the building’s future as the city’s main library is now being threatened.

Is this a case similar to another amazing civic work by Rudolph: his now-disfigured Orange County Government Center? There, a greater recognition of the building’s architectural value and excellence might have—whatever the problems—brought forth the commitment and resources to fix them. We hope that such understanding and support will come forth for the library in Niagara Falls—that it “gets some love”.

INTO THE FUTURE?

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation will be following the fate of Niagara Falls’ Brydges Library (and working to preserve it.) We’ll be bringing you ongoing news of this in the coming months—and if you hear anything about the future of the building, please do let us know!

The entry side of Niagara Falls’Earl. W. Brydges Library, designed by Paul Rudolph. Image courtesy of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, photograph by G. E. Kidder Smith