Paul Rudolph’s 100th birthday inspired the creation of two exhibits devoted to him—and those shows’ catalogs have received good reviews.

Ernst Wagner: Fighting to Preserve the Legacy of Paul Rudolph

Brutalism - In Home Decoration ? (Yes.)

S.O.S. Update # 4 : Proposed Demo & Development at Rudolph's Boston Government Service Center

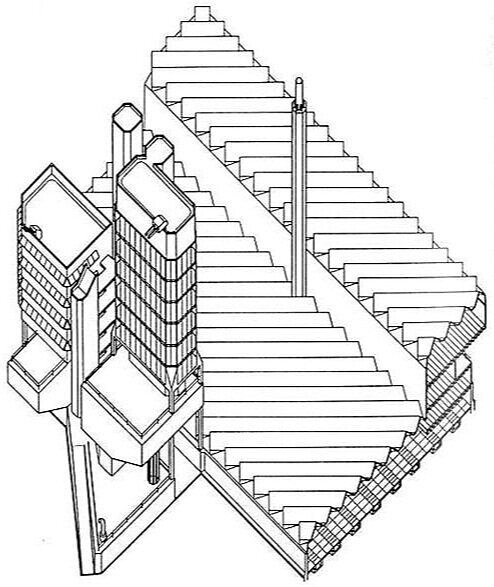

Paul Rudolph’s original, overall conception for the Boston Government Service Center included a tower (which, unfortunately, was not built). The proposed development of the site brings up a serious question: Would/could new construction be as harmonious (with the existing buildings) as the design Rudolph created? Rendering by Helmut Jacoby. The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

In this developing story, the state of Massachusetts’ Division of Capital Asset Management & Maintenance issued a power point presentation about their redevelopment proposal for the Boston Government Service Center—one of Paul Rudolph’s largest urban civic commissions. We’ve been looking at the various slides in their power point “deck” and examining the various assertions they make—and bringing forth our sincere and serious questions.

In previous posts we’ve looked at the ideas (as shown in their presentation) on the current building, development, how current occupants of the building would be handled, etc… —and offered our concerns about each.

Let’s look at the their next two slides:

WHAT WILL BE DEVELOPED THERE?

Following each of the slide’s points, we offer responses/questions:

The redevelopment partner that the state chooses will be responsible for planning, financing, and permitting the redevelopment.

The key word here is: planning—and we ask: How are they getting input during that process? And from what stakeholders? (and how is it weighted, and who has a veto?)

This process will be subject to Large Development Review by the Boston Planning and Development Agency under Article 80, and to review by MEPA.

It would be useful to all parties to lay this out in more detail, so that all can see what’s involved—and where (at what points) real input and interventions can be offered to improve all proposals.

The site is zoned for more intensive use than is currently realized. – Allowable Floor Area Ratio (FAR) is 8-10 (currently ~2.0).

Ideas about zoning (especially levels of density) change over time, as different planning theories and urban design schools-of-thought become popular and wane. Moreover, the question of desirable density is subject to political pressures. What makes a good building/public space/block/street is not always determined by zoning codes, equations, or the theories of the moment.

Generally, height is limited to 125’ towards the street edges, and up to 400’ on the interior.

Perhaps they’re saying that those are the current code’s height limits, which a developer must work within. It would be useful to know if that is the intent, or if there are other consequences.

Planned Development Areas (PDAs) are allowed on a portion of the site. The redevelopment partner may use the PDA process in order to allow the site to be more thoughtfully planned.

The consequences of this statement are not clear, and it would be useful to know more about PDA’s. The phrase “more thoughtfully planned” begs the question: more than what?

And let’s consider their next slide:

hISTORIC PRESERVATION APPROACH

Following each of this slide’s points, we offer our responses/questions:

DCAMM’s approach to redevelopment will acknowledge the architecturally significant elements of the Hurley-Lindemann site, while addressing its flaws.

The language begs the question about the building having flaws—-whose nature and quantity is unspecified. Any building can probably be renovated over time, and made more congruent with current needs—and we need clarity on what’s claimed and what’s proposed.

The Government Services Center complex was planned by prominent architect Paul Rudolph.

Yes, Paul Rudolph conceived of the overall plan and design: it is one of his major urban-civic buildings.

The complex was meant to include three buildings, but only two of the original buildings were built (Brooke courthouse was added later).

It is unfortunate that the scheme was not fully realized.

The Lindemann Mental Health Center was also designed by Rudolph, and is more architecturally significant than the Hurley building.

This project was designed as a set connected buildings that are strongly related—with a level of coordination in design that would create a feeling of wholeness to the block. That sense of wholeness is fundamental to good architecture—and is something to which Paul Rudolph was committed. Setting-up one building against the other is contrary to the way the complex was conceived and designed—and one can even see this from Rudolph’s earliest sketch.

DCAMM is required to file a Project Notification Form (PNF) with the Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC). DCAMM will then work with MHC to develop a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) regarding future development at the site.

It would be useful to know more about this process, how it functions, and how input is received from all interested parties—and, in this case, what ingredients go into creating a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA).

NEXT STEPS: LISTENING AND ACTING

We will continue to respectfully review the state’s proposals—and raise sincere questions when appropriate.

If you have information or insights to contribute, for preserving this important civic building by Paul Rudolph, please let us know at:

office@paulrudolphheritagefoundation.org

Paul Rudolph’s original sketch for the layout of the Boston Government Service Center. The drawing summarizes the overall concept of having the set of strongly related buildings wrapping around the triangular site—with a large, open plaza in the center.. A tower is indicated by the hatched pinwheel-shape toward the middle. © The estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

S.O.S. Update # 3 : Proposed Demo & Development at Rudolph's Boston Government Service Center

The publicly accessible courtyard at the center of of Paul Rudolph’s Boston Government Service Center. While one sometimes hears accusations against the building, it should be equally noted that it is also a public oasis of green and peace. Photo courtesy of UMASS

In this developing story, the state of Massachusetts’ Division of Capital Asset Management & Maintenance has issued a power point deck about their redevelopment proposal; We’ve been looking at the various assertions they put forth—and offering our sincere and serious questions and concerns.

We’ve looked at (and offered our questions about) the first set of their powerpoint slides, and then did so with a second set.

Let’s look at the next two:

PLANS FOR CURRENT BUILDING OCCUPANTS

Following each of the slide’s points, we offer responses/questions:

DCAMM will work with all occupants and relevant union leadership to find temporary and permanent relocation space that suits agency operational needs in a cost-effective way.

With any relocation of multiple departments and numerous staff, the question must be asked: How much disruption to services (and employee lives) will be caused by this? -and- For how long? We understand that promises based on projected timelines are offered in good faith—but often projects are delayed (sometimes for years) by unexpected factors (for example: construction delays, changing budgetary priorities, changes in administrative structure, changes in leadership….) So: however long the relocation/disruption/dislocation has been projected to last, in reality is could go on for much longer.

Current plans entail the majority of EOLWD employees who currently work at the Hurley Building returning to the redeveloped site.

Since the development plans are not even sketched out, on what basis can this promise be made?

No state employees will lose their jobs as a result of this redevelopment.

Same as above: plans are not even known—on what basis can promises be made?

Employees will remain in or near Boston, in transit accessible locations

What’s meant by near and transit accessible needs to be defined.

And let us consider the next slide:

US DEPARTMENT OF LABOR

Following each of this slide’s points, we offer our responses/questions:

The US Department of Labor funded the initial construction and site acquisition of the Hurley Building, and still has a significant amount of equity in the site.

It would be useful to know the extent of the equity, and the tangible consequences of this statement.

As required by federal rules, the Commonwealth is working with USDOL to ensure that federal equity is used to further the work of the Commonwealth’s Labor and Workforce Development agencies.

Here too, it would be useful to have things made more explicit: What rules are being invoked? What federal equity is being referred to? and overall: What are the consequences of this statement?

NEXT STEPS: LISTENING AND ACTING

We will continue to respectfully review the state’s proposals (and raise questions when items need review or clarification.)

If you have information / resources / insights to contribute, for preserving this important civic building by Paul Rudolph, please let us know at:

office@paulrudolphheritagefoundation.org

Even with a few signs of a coming Fall, the center plaza’s oasis is still very green! Photo © the estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

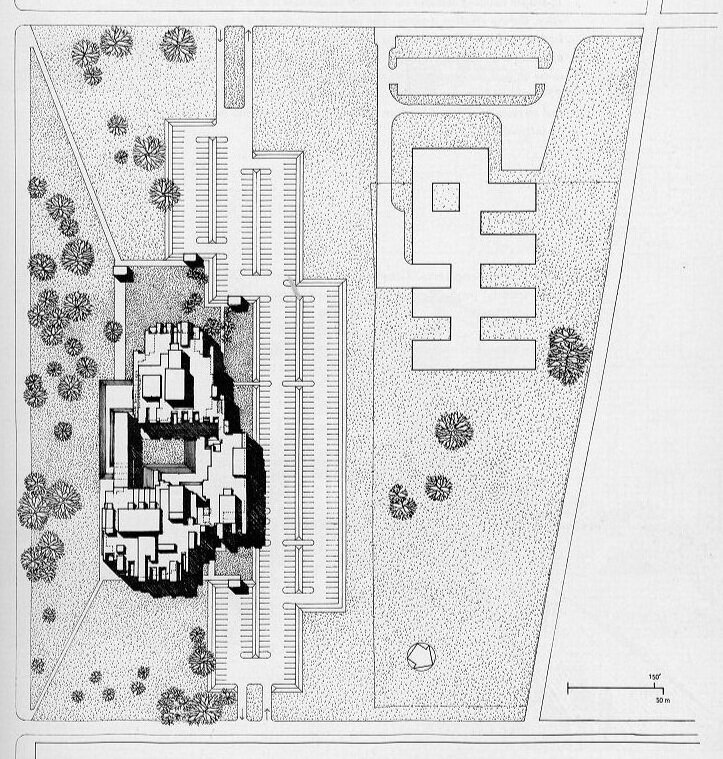

S.O.S. Update # 2 : Proposed Demo & Development at Rudolph's Boston Government Service Center

For context, it may be useful to look at the overall plan of Boston’s Government Center area, which was laid out by I.M. Pei. There are several prominent buildings in the area, which were all built as part of the development of this center. The large rectangular building (near the center of this drawing) is the Boston City Hall (by Kalllmann, McKinnell & Knowles). The large, gently curving building to its left is Center Plaza (built as offices and ground-floor retail) designed by Welton Becket. Rudolph’s Government Service Center follows the perimeter of the triangular site at the map’s upper-left. About equidistant between the City Hall and the Government Service Canter are the two towers (shown as offset rectangles) of the John F. Kennedy Federal Building by Walter Gropius and The Architects Collaborative. Quincy Market, the celebrated food marketplace, is the long, horizontal, dark rectangle at the far right. It was designed by Alexander Parris and built in the early 19th Century.

Here’s a satellite view of the same area as shown in the drawing at the top of this post (and shown at approximately the same scale.) If you look at the drawing above, the entire site for Government Service Center was to be utilized for its building (plus the outdoor plazas, also designed by Rudolph)—and there was to be a tower in the center. In the photo above, one can see that the tower was not built, and the right-hand side of the site is now occupied by a wedge-shaped structure which was constructed later: it’s a municipal courthouse building, designed by another firm. Image courtesy of Google: Imagery ©2019 Google, Imagery

As we mentioned in our last update on this developing story, the State of Massachusetts’ Division of Capital Asset Management & Maintenance has issued a power point deck about the redevelopment proposal. In our last posting, we looked at their first slide: “Hurley Building at a Crossroads” (which was about the current condition and challenges of the building)—and offered our sincere questions and concerns.

Now it’s time to go a bit deeper into the deck, and consider the state’s further assertions and proposals. Let’s look at the next two:

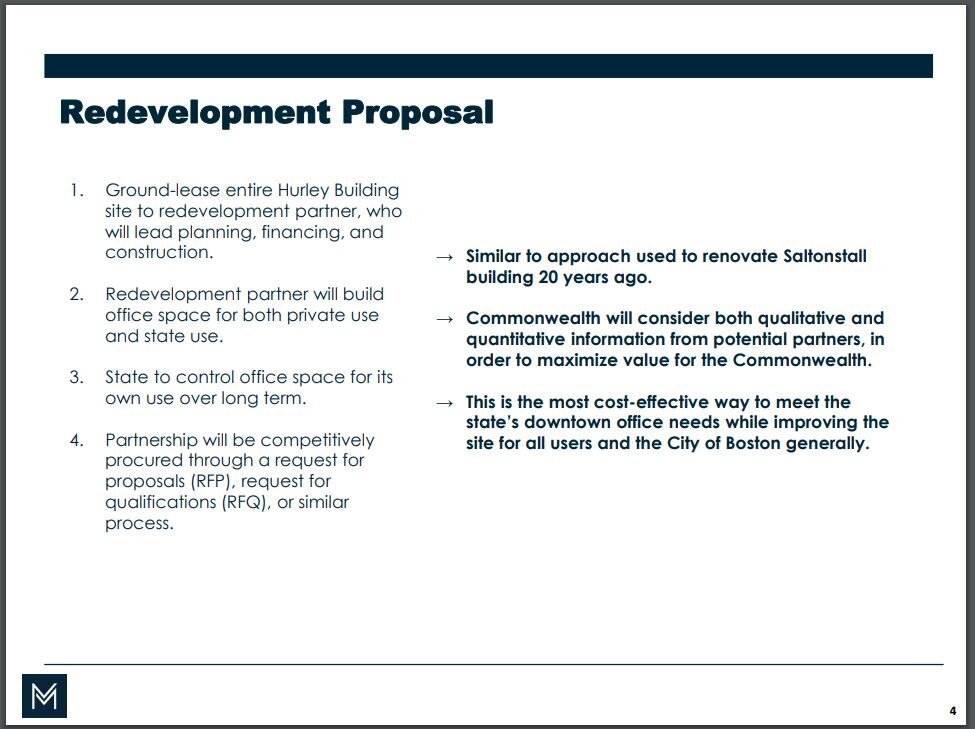

REDEVELOPMENT PROPOSAL

Following each of the slide’s points, we offer responses/questions:

Ground-lease entire Hurley Building site to redevelopment partner, who will lead planning, financing, and construction.

Shouldn’t there be a wider array of input from the beginning, to achieve good, public-spirited design? That would be lost if the development process is walled-off at its beginning—only soliciting public input later, (after the parameters seem to have been set). Without getting public input early it, it can lead to less-than-optimal results for the state and its citizens.

Redevelopment partner will build office space for both private use and state use.

It would be useful to know how the ratio determined?

State to control office space for its own use over long term.

It is important that the definition of “long term” be made explicit. If there’s a termination date to that agreement, then—at that end-date—how are disruptions to be avoided? Conversely: the state already owns the site—so, as long as they are their own tenant, there’s no need to worry about end-dates.

Partnership will be competitively procured through a request for proposals (RFP), request for qualifications (RFQ), or similar

It’s important to keep in mind that the overall proposal requires turning public space and buildings over to private use. Occasionally this can be done as a win-win situation, but it depends on many factors—and one of them is the quality and track-record of the development partner. So a key question is: Will the qualifications examine whether the developer has a real record of tangibly “giving back” (through the quality of what they build/plan)?

Similar to approach used to renovate Saltonstall building 20 years ago.

It would clarify things if we were told by what set of standards that success was judged—and how that was measured, and how far the project went to fulfill that.

Commonwealth will consider both qualitative and quantitative information from potential partners, in order to maximize value for the Commonwealth.

It would be useful to all parties if the above terms could be clarified—particularly the qualitative aspect.

This is the most cost-effective way to meet the state’s downtown office needs while improving the site for all users and the City of Boston generally.

Much is condensed into this one sentence. Implicit are assertions about: cost-effectiveness, state needs, the nature of the improvements, and who the users are. These would each need careful definition and review.

Lets consider the next slide:

EXPECTED BENEFITS

Following each of this slide’s points, we offer our responses/questions:

New, modern office space for state employees for same or less cost than comparable space elsewhere.

Renovation can usually yield modernization as comparable/less cost---if done efficiently. Moreover, renovation is almost always the greener alternative.

Long-term cost stability for both capital and operating budgets.

It would be good to know what this is this being compared to.

Improved public realm across 8-acre block. Increased site utilization and activation.

There’s abundant knowledge, from today’s public space designers, about making plazas and public spaces more alive and used—and many good case-studies of success. Don’t destroy what we have—but, instead, use that knowledge to make these unique spaces more alive to the public.

Economic benefits from large-scale development (jobs, tax revenue, etc.).

What’s often missing from balance-sheet are the costs of over-(“large scale”) development: especially overburdening the already under-pressure transit system and city services. Jobs will also be created through the modernization of the existing building.

NEXT STEPS

We’ll continue to respectfully review the state’s proposals—and raise questions when items need review an clarification.

If you have information or resources to contribute to preserving this important building by Paul Rudolph, please let us know at:

office@paulrudolphheritagefoundation.org

The overall design for the Boston Government Service Center. Although it is the work of a team of archiects, the design leader was Paul Rudolph-and it is truly his conception. This axonometric drawing shows his original full design for the complex—including public plazas in the center and at the three corners. In the middle was to be a tower with a “pinwheel”-shaped plan (in this drawing only the first few floors of it are shown.) © The Paul Rudolph estate, Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Rudolph and Radio

S.O.S. - Boston Government Center Update: Considering the Development Proposal's Assessment of Rudolph's Building

Our New Project Atlas puts Rudolph on the Map (literally)

S.O.S: - Save Rudolph's Boston Government Service Center

Good Old Books—and the Fight for Residential Modernism (including Rudolph)

Happy Birthday, Paul Rudolph — it's his 101st !

Rudolph in a happy mood, at the street level of one of his most compelling buildings: his about-to-be-completed Temple Street Garage in New Haven.

It’s October 23—and we celebrate Paul Rudolph’s Birth 101 years ago today (and invite you to do so too!)

This past year—Rudolph’s centenary—has been a year of “Rudolph-ian” accomplishment: in preservation, research, education, scholarship, and—perhaps most important—in creating a growing awareness and appreciation of the legacy of this great architect. But—

But rather than review the achievements of the last year (you can read of many examples in past articles on this blog) we thought it would be nice to just share some images of him—and different ones than you normally see.

Portraits of architects usually show them in a serious mode, with solemn expressions suitable for a person embarking on a great artistic or constructional task. Paul Rudolph was no exception: most pictures of him show a deeply thoughtful figure, or one engaged in disciplined, critical work.

But today we offer a couple of pictures of another, sunnier side of Rudolph—ones where the architect was clearly in a smiling, happy state.

Paul Rudolph in formal attire—with more than a hint of a smile. By-the-way: that’s not smoke in the background (as we had first thought—but Rudolph was never a smoker.) What’s [visually] suggesting smoke is light catching the curving edges of a topographic model., shown here tipped vertically to hang on a wall. Such models are part of the architectural design and presentation process—and this one might have been made, in Rudolph’s office, for one of his projects.

So Happy Birthday, Mr. Rudolph — and we look forward to your next century !

Not Just Perspectives (Rudolph Could Draw In Other Ways Too): The Axonometric FACTOR

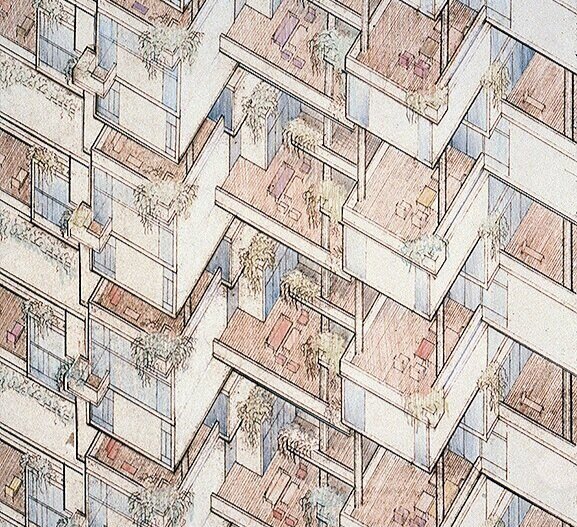

A detail from Paul Rudolph’s drawing for the Colonnade Condominiums in Singapore (a project built in the final phase of Rudolph’s career, when he was doing much work in Asia.) While Rudolph is famous for his perspective drawings, here he is using an “axononmetric” drawing technique—which was unusual for him, but is not unknown in his graphic oeuvre. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

MASTER OF PERSPECTIVE

Well of course Rudolph could draw—beautifully, masterfully, with stunning skill. His fame is intertwined with his brilliant perspective drawings (including, and especially, his perspective-sections). He made them starting right from the beginning of his career—indeed, while he was still a student, as the below example shows:

“Weekend House for an Architect”—a school project of the mid-1940’s, when Rudolph was finishing his Masters at Harvard—and an early example of the intense perspective rendering style which he’d use for the rest of his half-century career (and for which he became famous.) © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

While much has been written about Rudolph’s drawings, little-known is Rudolph’s own text on the topic, which speaks of his overall approach and attitude to drawing. The essay, “From Conception to Sketch to Rendering to Building" forms the introduction to the magnificent book, Paul Rudolph: Architectural Drawings. The book came out in the early 1970’s, and was published by the great Japanese architectural photographer, Yukio Futagawa. Futagawa had, in previous years, extensively photographed Rudolph’s work, and had also created a publishing firm (still extant) focused on architecture.

The best presentation of Paul Rudolph’s drawings is this large-format book, “Paul Rudolph: Architectural Drawings.” The cover features one of the perspective-sections for which the architect was so well-known—this one through the body of the Burroughs Wellcome headquarters building. The book was published by Yukio Futagawa (who had made superb photographs of Rudolph’s work—and whom Rudolph greatly admired.)

In that essay, Rudolph says:

“It should be noted that the drawings and renderings shown here were done over a period of almost thirty years, but the technique used for them has changed very little. During my school years and immediately thereafter I searched for a technique of drawing which would allow my personal vision to be suggested, and after a period of searching, arrived at the systems shown in this book.”

Rudolph’s drawings (and especially his use of perspective-section drawings) has been widely remarked upon—most extensively written about by the author of the comprehensive study of Rudolph, Timothy M. Rohan—particularly in an essay by him in a recent book devoted to Rudolphian studies. In an earlier post we addressed Rudolph’s focus on sections—and there you can find further information on that topic.

Perhaps Rudolph’s most famous drawing is this one, done near the height of his career: his perspective-section through the Yale Art & Architecture Building (now known as Rudolph Hall). Space, light, scale, and structure are conveyed simultaneously. There is a vivid sense of depth—and a strong effort is made to communicate spacial relationships among the various levels. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

BUT RUDOLPH DID USE OTHER TECHNIQUES…

A review of Rudolph’s drawings—which number in the hundreds-of-thousands—show that he used a variety of techniques:

Plans

Sections (including Site-Sections)

Elevations

1-Point Perspective

2-point Perspective (including—though rarely—where the 2nd perspective is a vertical one, with the vanishing-point below-ground)

Plan-Perspectives

Section-Perspectives

Diagrams

Quick Sketches (ranging from schematic doodles to more advanced studies—the sorts of visual overtures a designer makes, for themselves, when considering an idea)

Isometrics

Axonometrics

That’s the graphic tool-kit of any architect—the “armamentarium” of all designers. Such techniques are used to solve problems, to present proposed solutions to clients and government bodies, and ultimately to communicate instructions and intentions to builders [and when H.H. Richardson said that the first principle of architecture is “Get the job!”, he could well have added that drawings are a marketing tool.]

Rudolph is most well-known for his section-perspectives—but he wielded all of the above. It is the last type of drawing on that list, axonometric—one rarely discussed in Rudolphian studies—which deserves attention.

PERSPECTIVE IS NOT THE ONLY WAY

Perspective drawing—that great innovation of the Renaissance—uses lines which seem to converge, and spaces the lines so that objects which are further away are drawn smaller. This gives perspective drawings a similarity to the way we naturally see.

But there are other ways to draw, used by designers, which don’t act in the same way as perspective drawings. It may seem counter-intuitive to use anything but perspective drawings, as they create a simulation which is closest to the way we perceive things—but there are times when one can covey a great deal of complex information by using other-than-perspective approaches.

Isometric drawings and Axonometric drawings are the main alternatives—and they can be combined with other techniques (like sections). Auguste Choisy, an historian and teacher of the French Beaux-Arts era, was famous for his ability to combine plan, section, and elevation into a single drawing—and thus convey architectural information about a building in a coordinated and concise way. Here’s an example from one of Choisy’s books of architectural history:

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Auguste Choisy (1841-1909) published several architectural history books, in which he used his technique of combining the plan, section, and elevation of a building (or a representative part of a building) into a single drawing. This example shows how informationally potent such a combination could be: much is conveyed—particularly how each aspect of the building coordinates with the others. In this drawing, Choisy is showing the various planes (plan, section, and elevation) as isometric views. Thus areas that would be squares or rectangles are modified into diamond-like shapes—but that seeming “distortion” allows Choisy to fit all the planes together in a coordinated way. Choisy also used axonometric drawings in his books.

How would Rudolph have come to know about such other-than-perspective drawing techniques?

Rudolph’s disparaging remark about his first architecture school (in Alabama, before he went to Harvard) has been frequently quoted. He is reported to have said that their “faculty was best when they left you alone.” That’s been taken to mean that he got nothing out of the traditional, classically-based curriculum which the school offered. Yet in his extended conversation with Peter Blake, another side emerges. Rudolph declared:

“I have always felt lucky that I started studying architecture in a school that followed the Beaux-Arts system.”

Choisy’s architectural history books were well-known within Beaux-Arts educational culture. It is possible that, in such a traditional school as Rudolph attended, he would have been exposed to them—including their drawings with their use of isometric and axonometric techniques.

ISOMETRIC VS. AXONOMETRIC

There’s some controversy about the exact terminology for those two related-but-different drawing techniques—but one thing is clear: they’re both part of the same family: Paraline drawings. Without getting into a full tutorial on drawing methodologies, it’s useful to distinguish them:

In the family of Paraline drawings, sets of lines—for example: the lines that define all the vertical edges of the walls) are parallel to each other.

With Isometric drawings, one main plane (like the plan or the roof) is distorted—for example: if a part of the plan would in reality be a square, then on the drawing it would be shown as a diamond-like shape. Also, all the vertical edges of the walls are perpendicular to the bottom of the drawing.

With Axonometric drawings, the main plane (for example: the plan) would not be distorted: so a square would remain a square, and a rectangle would remain a rectangle. Also, the other sets of lines (like the vertical edges of the walls) are all parallel to each other.

Here’s a drawing that shows the difference between Isometric and Axonometric drawings.

Two approaches to drawing a rectilinear volume (which could be a brick, a building, a part of a building, or a room…):

The isometric Drawing, at the far-Left, distorts the top and bottom [plan] surface, and all the other planes too—making them into diamond-like shapes.

But the two examples of axonometric drawings shown here preserve the exact shape of the upper and bottom planes. Two variants are shown here: the Middle version, where the angle of the plan is tipped up equally on both sides (at 45 degrees); and the one at the Right, where the plan is tipped up un-equally (which leads to a more realistic look).

In both these versions of axonometric drawings, the vertical edges of the walls are perpendicular to the ground (the bottom edge of the drawing)—but sometimes, for clarity, other angles are used (like in the Edersheim Apartment example, below.)

AXONOMETRIC DRAWINGS BY ARCHITECTS

Axonometric drawings are beloved by generations of architecture students: they allow one to quickly create a convincing-looking drawing (one that has a sense of volume, but also maintains all the parts and proportions in proper relationship to each other). All one has to do is draw a plan, and then draw (“pull”) lines down from the corners to show the walls. Presto!—the drawing is ready to bring to class.

But professionals have also been using axonometric drawings for decades—and they’ve come in-an-out of popularity during the Modern movement in architecture. Some designers, like the ones associated with De Stijl, favored it (as it probably corresponded well with their overall rectilinear aesthetic.) Here’s an example from Theo Van Doesburg:

Study for “Design for Cité de Circulation,” a district with residential blocks by Theo van Doesburg: a pencil and ink drawing made circa 1929. It is a good example of an axonometric drawing: the planes of the buildings’ roofs and bases remain undistorted (in this case, a composition mainly of squares). The drawing shown, via Wikipedia, is in the public domain, as per PD-US or other provisions.

In the 1960’s-70’s, axonometric drawings came to prominence again, most notably in the work of James Stirling and Peter Eisenman (in the drawings for Eisenman’s early series of numbered houses).

Here’s a well-known example by Sterling:

James Stirling’s drawing for the Engineering Building at Leicester University—one of the most famous axonometric drawings of the post-World War II era. As with all axonometric drawings, the plan shapes (for example the rectilinear top surfaces the towers and terraces) are un-distorted: if they’re rectangles or squares in reality, then they’re shown as rectangles or squares in this axonometric drawing. As is frequently the case, the vertical lines of the walls are shown perpendicular to the ground.

RUDOLPH’S USE OF tHE AXONOMETRIC tECHNIQUE

Paul Rudolph did, from time-to-time, turn to axonometrics. But why, with his profound mastery of the perspective technique, did Rudolph sometimes use this alternative way of drawing?

To answer that, it would be good to look at some examples:

The Edersheim Apartment in New York

When we were creating 2018’s Paul Rudolph centenary exhibition, Paul Rudolph: The Personal Laboratory, one of the projects included was the apartment he had created for the Edersheim family: a complex of rooms occupying a full floor in a Manhattan apartment house. The program is complex, the rooms are plentiful, and each room is shaped to match its function (as was the custom furniture—built-in and freestanding—which Rudolph designed for those rooms.) Moreover, as is typical in New York City (even in luxury apartment houses like the one in which this apartment sits), there’s little room to spare. So all the above must be densely packed together—a challenge for any designer to work out. Then, once the design is solved, as it is a further of a challenge convey such a complex design to the client.

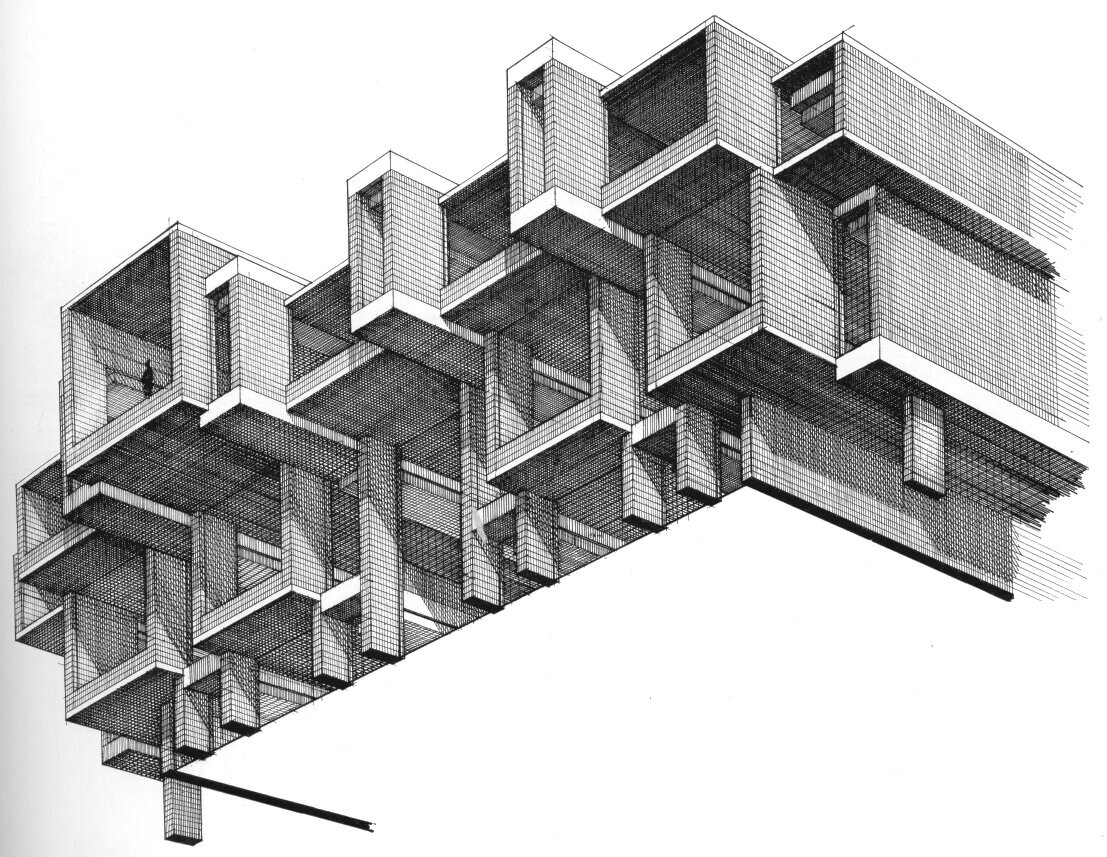

To make this whole assemblage of spaces understandable to the Edersheims, Rudolph created this drawing—an axonometric!

The Edersheim apartment, on New York’s Upper East Side—a Rudolph project from 1970. Rudolph used an axonometric view: and it looks as though the roof has been lifted-off and one is looking down into the apartment’s many multi-shaped spaces. Despite the complexity of the design, it is still understandable—and what helps create clarity is the fact that Rudolph here used the axonometric technique: the plan-shapes of the rooms are un-distorted, and also the building’s perimeter walls are drawn true to their actual shapes. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Below is an enlarged portion of the above drawing, showing one of the most complex parts of the apartment. It’s a fine example of how an axonometric drawing can be used to show, with clarity, even intricate arrangements of spaces and architectural elements.

An enlargement of a portion of the above axonometric drawing of the Edersheim Apartment. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

The Colonnade Condominiums in Singapore

The Colonnade is one of the most sought-after places to live in Singapore, with each high-rise apartment demanding luxury-level prices. In this 1970 project, Rudolph wove together a multitude of multi-level apartments into a rich composition, whose overall effect is a shimmering geometric dance.

Paul Rudolph’s Colonnade Condominium in Singapore—a project of the early 1970’s. In the subsequent decades, he would do numerous projects throughout Asia.

To communicate his intentions—which included a complex arrangement of interleaving balconies and windows—Rudolph used a variety of types of drawings: plans, perspectives—and the axonometric drawing seen at the top of this article.

The Orange County Government Center in Goshen, NY

In the middle-1960’s, Paul Rudolph started upon one of his most compositionally and spatially rich government buildings—a civic brother to his Yale Art & Architecture Building. The structure—or rather, compound of structures—that he built in Goshen embraced a complex program to answer the civic needs of the region’s citizens: one could do anything there from getting a marriage license to being tried for serious crimes.

Paul Rudolph’s Orange County Government Center in Goshen, NYC—as seen before it was demolished and/or altered to the point where Rudolph’s design has been all-but-erased.

For this project, Rudolph used a variety of drawings to explore the design and convey his intent.

Did he use perspectives? Certainly—and here’s his perspective drawing for the exterior:

Paul Rudolph’s perspective rendering of the Orange County Government Center. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Did he use any isometric drawings? Yes—and here’s his study of projecting and receding masses and window openings—a tour de force of levitating masonry.

An isometric drawing, by Rudolph, looking up at a portion of the Orange County Government Center building. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

But when it came to the roof—a complex landscape of rising, overlapping, and interpenetrating rectilinear masses (in a plenitude of sizes)—he used an axonometric view:

Paul Rudolph’s drawing of the roofscape and masses of Orange County Government Center. The three main masses of the building—left, top, and right right—surround a courtyard. Rendered as an axonometric, probably no other drawing technique would have as clearly conveyed the overall conception of the building’s massing, as well as the complexity of its composition. Rudolph, aware that dignity is as important as basic function (especially in civic buildings), created a modern version of a stately entry: there is an elongated plane, set high, spanning across the southern side of the courtyard (shown at the bottom-center of this drawing)—and that created a space-defining gateway to the complex. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Paul Rudolph’s site plan for the Orange County Government Center. Something of the richness of the design is communicated by his using an axonometric view (conveyed by the shadows) to render the variety of masses from which the building is composed. N.B.: in this drawing, the body of the building has been turned 90 degrees, clockwise, from the view above. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

AXONOMETRICS FOR RUDOLPH?—iT’S A mATTER OF PRACTICALITY

Rudolph is sometimes characterized as the very embodiment of the heroically individualist genius architect. There’s a lot of truth in that—with consequences, good and bad. One of the negatives is that one can then get tagged as being impractical or hard to work with.

Paul Rudolph shows that this is not necessarily the case: he had a 50-year career, with over 300 commissions—and some clients report on what a pleasure it was to work with him (and some became repeat clients—the ultimate accolade in client relations.) Moreover, Rudolph got things built—all over the country, internationally, doing numerous types and sizes of building, and at every budget level—so he had a track record of being practical.

Architectural drawings—though they are artistic creations—are equally tools: the means by which an architect conveys his ideas to clients and builders. Edwin Lutyens, speaking of construction drawings, likened them to writing a letter, telling the builder what to do. Drawings must communicate with clarity, whether it be the specifics of a construction detail, a building’s overall composition, or even the flavor of a design. Rudolph most often chose perspective drawings as the most effective way to communicate his intentions—but as a practical architect, he knew there were other techniques which could be more effective in specific situations. Rudolph mastered those techniques and used them too—and as a result we have some fascinating axonometric drawings from him.

Rudolph Writing: Quotations from an Architect

Paul Rudolph—at the writer’s task. It’s worth noting that the book which he’s leaning against is the the most complete monograph on the Yale Art & Architecture Building ever produced (other than the fine collection of photographs by Ezra Stoller). The book, published by Jaca in Italy, includes extensive analytical and measured drawings. © The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

When we were putting together the exhibits and catalogs for Paul Rudolph’s 2019 centenary, we infused them with quotations from the architect: ones which were pertinent to the various facets of the exhibits—and which allowed Rudolph to speak directly to the viewer.

In the course of that research for the centenary, and in subsequent work (answering questions from journalists, writing these blog posts…) we accumulated a trove of fascinating Rudolph quotations—on a great variety of subjects—and we thought it would be good to share them.

RUDOLPH’S FAVORITE

The first one we want to share is a passage that Rudolph seemed to value above all others: he used it (or variations of it) over the years, sometimes at the end of a speech. Reading it today—and experiencing its force it induces—one can see why:

"We must understand that after all the building committees, the conflicting interests, the budget considerations, and the limitations of his fellow man have been taken into consideration, the architect’s responsibility has just begun. He must understand that exhilarating, awesome moment.

When he takes pencil in hand, and holds it poised above a white sheet of paper, he has suspended there all that has gone before and all that will ever be."

Paul Rudolph’s Pencils and Pens. Image: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

RUDOLPH QUOTATIONS

Here’s a selection of quotations from Rudolph’s various writings, speeches, and conversations. They indicate the many topics on which he focused, and are sometimes revealing of his creative process—the thinking of an architect who was both a practitioner and a teacher.

“We desperately need to relearn the art of disposing our buildings to create different kinds of space: the quiet, enclosed, isolated, shaded space; the hustling, bustling space, pungent with vitality; the paved, dignified, vast, sumptuous, even awe-inspiring space; the mysterious space; the transition space which defines, separates, and yet joins juxtaposed spaces of contrasting character. We need sequences of space which arouse one’s curiosity, give a sense of anticipation, which beckon and impel us to rush forward to find that releasing space which dominates, which acts as a climax and magnet, and gives direction.”

“The essential element in architecture is the manipulation of space. It is this essence which separates it from all other arts.”

“Things are quite chaotic. We are faced with a vast change of scale, new building forms which have not really been investigated, and the compulsions of the automobile. When faced with the truly new, the serious architect must search for solutions equally dramatic.”

“Architecture is a personal effort, and the fewer people coming between you and your work the better. … This is a very real problem, and you can only stretch one man so far. The heart can fall right out of a building during the production of working drawings, and sometimes you would not even recognize your own building unless you followed it through.”

“…we tend to build boxes and call them buildings.”

“I think every curve and line has to have real meaning; it cannot be arbitrary.”

“I’m pleased that the building touches people, and part of that is that people’s opinions oscillate about it. That’s okay. The worst fate from my viewpoint would be indifference.”

“In terms of how one goes about designing anything, you don't really know, or at least I don't know, until after the fact. There are so many elements that come into play that if you wait to figure out what it is you truly want to do once you have a project to work on there won't be enough time. You have to, as I see it, have a reservoir of things that you feel should be done and then you draw on that reservoir and hopefully apply elements from that reservoir in an intelligent fashion. Sometimes it doesn't work that way. Sometimes one is hell- bent for whatever reason to do certain things no matter what. That forcing can lead to obvious problems. You can have one hundred reasons why you do things after the fact. I'm just saying that for me it's a matter of getting your fingers on what you can and cannot do from a legal viewpoint, what it is the owner truly wants to do— but he doesn't necessarily tell you, you have to read between the lines— and what should be done ideally. … You have to know what's possible. Architecture is not a question of the purely theoretical if you're interested in building buildings. It's the art of what is possible.”

“I can say that in spite of all the rationalizations that architects go through, including myself, you can pay no attention to what architects say, you can only pay attention to what they do. The reason for that is a very real one. I'm compelled: I have no choice about certain combinations of forms, material, space, or architectural considerations. They egg me on. I know what they are, by and large— but not all of them— and I can be very clear about what they are. Now I can't tell you why spiraling space or the movement of space is what is so compelling for me, but it is. I can't tell you why the cantilever, the juxtaposition of forces, and the light and the heavy in terms of structure, is compelling, but it is. I can't tell you why the purposeful placement of architectural elements so that they catch the light in certain ways is compelling, but it is. I can't tell you why certain combinations of handling scale, which is for me second only to space in its importance, is compelling, but it is. I can't tell you why asymmetry as a method of organizing things is so much more compelling than symmetry— I think I've worked on two symmetrical buildings— but it is. ... All I'm really saying is that the most rational architect in the world is not to be trusted at all because there is no such thing as true rationalism when you are speaking of architecture. I can only tell you that I am totally turned off by certain things: the whole of Postmodernism, to start with. I'm equally turned on by certain elements of architecture. I used to wonder about that myself, but now I no longer wonder. I think it's an absolute nature of architecture.”

“Always, always, always, everything, everything, everything at the beginning. I'm a great believer in the big bang. You cannot isolate parts, ever. That's the reason why it's so important to know as much detail as possible at the very beginning.”

“Every man wants to belong to a “place”; he wants to believe that he is in the most wonderful spot on earth and he takes pride in how and where he spends his time on this earth. Emotion is the most important determinant in architecture.”

“I think everybody should nourish every last personal idiosyncrasy.”

“Our domestic interiors are often dominated by storage of mechanical, electronic, entertaining, work-saving devices of all kinds. Since they must be continually replaced, the architectural accommodation influences and often dominates the interior space. Furniture and equipment become architecture.”

“Decoration can be thought of as a precious assemblage of selected parts which is poured over the structure in such a manner that the parts adhere to important junctions—the junction of building to base, base to support, support to supported, building to sky and most important, building to user—as manifest at entry and opening.”

“I'm very selective about who I'm interested in. I would go around the world to see a Corbu building or a Wright building. I wouldn't go across the street to see some things. It's really true. I know it sounds terrible, but it's absolutely true. Because I'm interested in feeling and understanding, I learn from traditional architecture; I don't learn from modern architecture by and large. That the reason why I feel really lucky that I've traveled as much as I have.”

"To me, the Barcelona Pavilion is Mies’ greatest building. It is one of the most human buildings I can think of—a rarity in the twentieth century. It is really fascinating to me to see the tentative nature of the Barcelona Pavilion. I am glad that Mies really wasn’t able to make up his mind about a lot of things—alignments in the marble panels, or the mullions, or the joints in the paving. Nothing quite lines up, all for very good reasons. It really humanizes the building.”

“Well, I am influenced by everything I see, hear, feel, smell, touch, and so on. The Barcelona Pavilion affected me emotionally. It is one of the great works of art of all time. I could not understand at first why it affected me as it did. I really never liked the outside of it. But the inside of the Pavilion transports you to another world, a more spiritual world.”

“You must understand that all my life I have been interested in architecture, but the puzzle for me, in many ways, is the relationship of Wright to the International Stylists. Now perhaps for you that seems beside the point, or very, very strange. It has a little bit to do with when you come into this world, and that is when I came to grow. Wright’s interest in structure was, to a degree. a psychological one. I am fascinated by his ability to juxtapose the very heavy, which is probably most clear, almost blatant, too blatant, in Taliesin West with the very, very light tent roof. It isn’t that his structures are so clear, because they are not. It is that he bent the structure to form an appropriate space. He would make piers three times the size that they needed to be in order to make it seem really secure. Or he would make the eave line two or three inches deep by all sorts of shenanigans, from a structural point. My God, what did to achieve that, because he thought it ought to light. I would agree with him in a moment, but the International stylists would not. Well. they did and they didn’t. It was the bad ones who did not. They didn’t know how, didn’t know why.”

RUDOLPH WRITINGS

Rudolph wrote & lectured throughout his career—and if you are interested in learning more about his thinking, the most concentrated collection of the architect’s words are in a book edited by Nina Rappaport:

WRITINGS ON ARCHITECTURE by Paul Rudolph

It is published by the Yale School of Architecture and distributed by Yale University Press (and also available through Amazon.) The book contains not only essays by Rudolph, but also the texts of some of his speeches, as well as interviews.

![Paul Rudolph in formal attire—with more than a hint of a smile. By-the-way: that’s not smoke in the background (as we had first thought—but Rudolph was never a smoker.) What’s [visually] suggesting smoke is light catching the curving edges of a topo…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1571777213382-QGDGH7LPXF8Z7BKOURQM/Rudolph+in+tux.jpg)

![Two approaches to drawing a rectilinear volume (which could be a brick, a building, a part of a building, or a room…):The isometric Drawing, at the far-Left, distorts the top and bottom [plan] surface, and all the other planes too—making them into d…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1569611468636-M4EYPT5S2Q16MOXPGFUD/axonomtric%2Bdiagram-two%2Bangles.jpg)