“Upward Bound” by Charles Fayette Taylor—the other artwork which is part of the Boston Government Service Center. It is suspended within a colonnade of the Hurley Building and can be seen from the complex’s courtyard. Photo by Kelvin Dickinson © The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Architecture and Art (especially large-scale sculpture) have always been natural partners: one completes other— architecture creates a noble, well-scaled setting for artworks; and artworks are creative gifts of the highest human spirit, which can lift the entire composition.

Great archiects—including masters of the Modern movement like Wright, Mies and Corb—have always been cognizant of this, and have created or included artwork in their architectural designs (or at least have indicated intended locations in their renderings.)

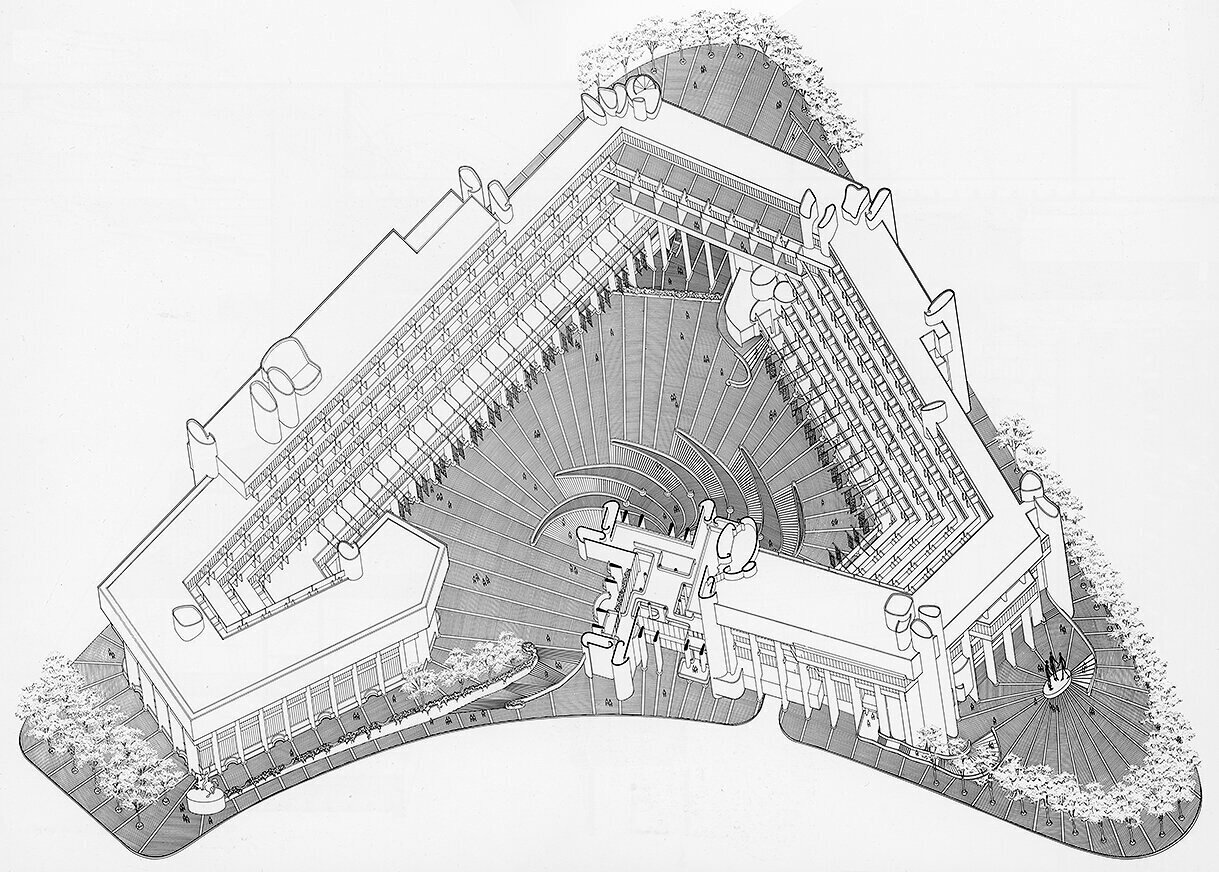

When Paul Rudolph was designing the Boston Government Service Center, his axonometric drawing of the complex showed two sculptures—and he placed them in the most public of locations: at prominent corners of the site. Rudolph said of the overall complex (and those locations):

“. . . .it is integrated into the surrounding fabric (at the street intersections there are small piazzas, one of Boston’s traditions).”

Paul Rudolph’s axonometric drawing of the overall Boston Government Service Center complex—including his concepts of how the exterior plazas would be handled. At the lower-left (Southern) and lower-right (Eastern) corners, Rudolph has placed sculptures in prominent locations. Enlargements of his drawings of those “placeholder” artworks are revealing (see below.) © The estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Though the artworks Rudolph included in his isometric drawing of the complex can be regarded as “placeholders,” they are still revealing of Rudolph’s awareness of the power of public sculpture—and they also showed his knowledge of art history (from which he could choose appropriate imagery.)

At the site’s Southern corner: Rudolph’s rendering of the complex shows a statue of a rearing horse and rider, situated on a high base. This is a type of sculpture (and pedestal) often seen in public spaces, and examples can be cited from the ancient Roman era to the the 20th century. © The estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

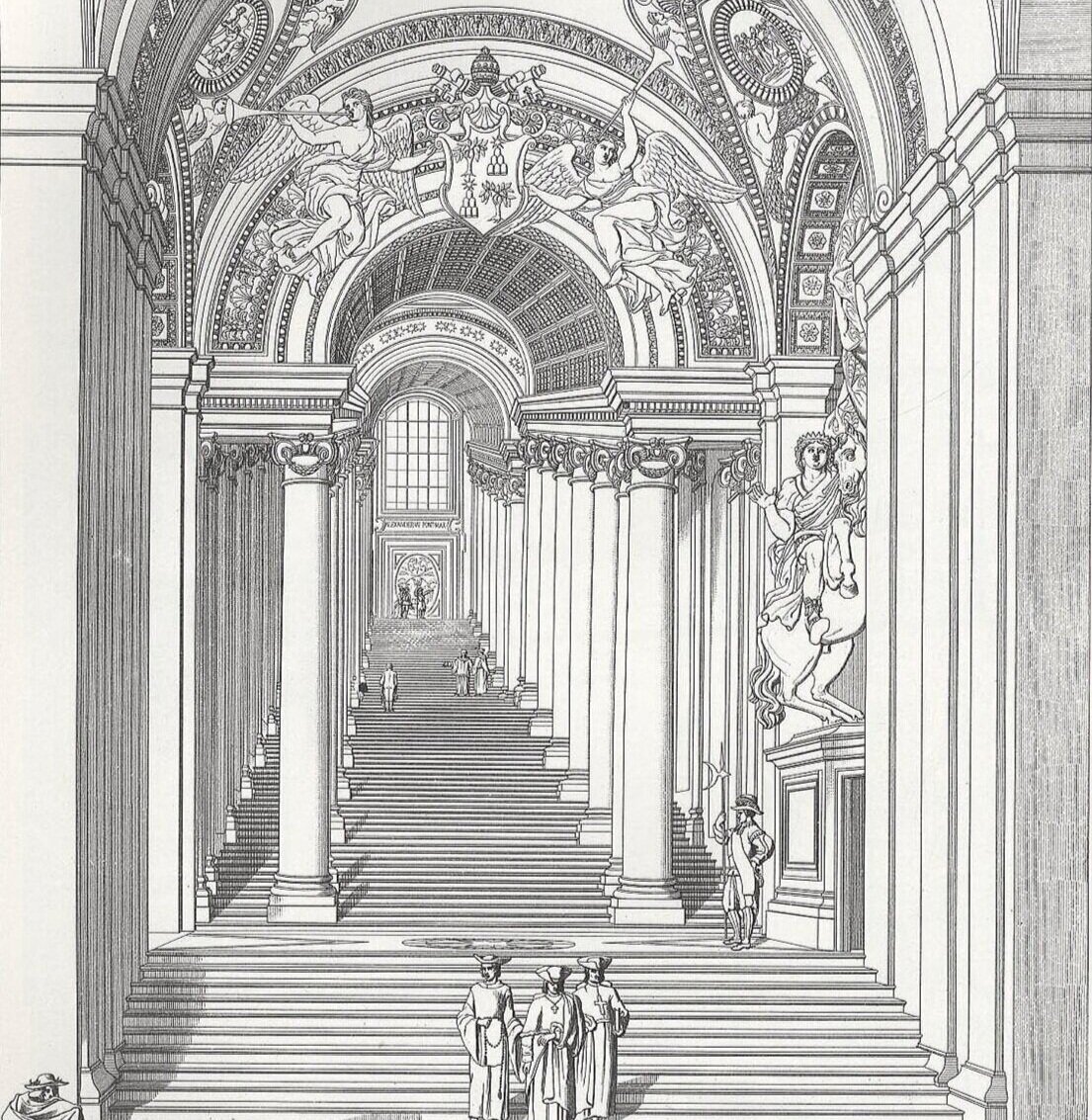

Rudolph’s possible artistic precedent: Paul Rudolph had seen Europe, for the first time, through receiving Harvard’s Wheelwright Prize (he traveled there from mid-1948 -to- mid-1949)—a trip that was, by his own account, a life-changing experience. A prime stop on any such “Grand Tour” would be St. Peter’s in Rome—and he would have been interested in one of that building’s most dramatic architectural features: the Scala Regia staircase. At a key intersection of the axes of the stairs and the main portico, Bernini’s rearing equestrian statue of Charlemagne dramatically terminates the cross-axis.

At the Eastern corner: Rudolph drew a sculpture of three elongated, stylized figures. They can be interpreted as isolated, yet simultaneously reaching out to each other—and are perhaps symbolic of some of the building’s clients, and the role the Boston Government Service Center could play in helping them. © The estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Rudolph’s possible artistic precedent: Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966) was one of the “Modern Masters” of 20th century art, and Paul Rudolph would have been well aware of his sculptural work. One of Giacometti’s recurrent motifs was an elongated human figure, sometimes shown alone, but also composed into loosely associated groups (as in in the example above.) These depictions of the human form are often interpreted as manifesting the loneliness or alienation of humanity in its present predicament. Photo by Paolo Monti, courtesy of Fondo Paolo Monti and the BEIC Foundation.

One of the two, large, site-specific murals by Constantino Nivola—which face each other in the main lobby of Hurley Building. Photograph © Peter Cachola Schmal, and used with permission.

Previous posts have focused on the work Constantino Nivola (1911-1988), an internationally respected artist who is well known for his sculptures and murals in public spaces. A pair of Nivola’s impressively-scaled, site-specific murals are in the lobby of the Hurley Building—a part of Paul Rudolph’s Boston Government Service Center. The state is proposing to sell the Hurley Building to a developer, which would result in the full-or-partial demolition of the building—and the possible loss of the Nivola murals.

There is another significant public artwork which is part of the Hurley Building. It too might be lost if the march to the demolition is not stopped…

“Upward Bound” is a sculpture by Charles Fayette Taylor, suspended within the Hurley Building’s colonnade. An ensemble of elongated metallic forms, they are each composed of tubular-shaped parallel elements. These large forms interpenetrate in a dramatic fashion—creating a vivid presence within the space. Photo by Kelvin Dickinson © The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

A portion of a press release, from MIT, celebrating the life and work of Charles Fayette Taylor. Part of it reads: “Professor Fay Taylor lived to be 102. The photograph below, taken at the occasion of the unveiling of one of his sculptures in the Sloan Automotive Laboratory at MIT in March 1987, shows Fay Taylor on the right. . . .”

“Upward Bound” is a sculpture which is dramatically suspended within the colonnade on the north face of the Hurley Building It can be seen when visiting the Boston Government Center’s courtyard and looking southward.

The forms that make up this artwork—indeed, it’s title—may reveal the artist’s lifelong fascination with flight.

The sculptor, Charles Fayette Taylor (1894-1996)—over a lifespan that exceeded a century in length—had a prolific and varied career. Key points include:

He was most well-known as an innovative scientist-engineer, particularly in the fields of aeronautical and automotive engineering, with a focus on those vehicles’ engines.

He helped to design the engine for the plane that carried Charles Lindbergh on his solo flight across the Atlantic, and which was also used in Byrd’s first flight to the North Pole.

In the early 1920’s, Taylor was the engineer in charge of the U.S. Army's Air Service Laboratory, and it was there that he met Orville Wright—and in the mid-1920’s he was put in charge of airplane engine design and development at the Wright Aeronautical Corporation.

He was on the faculty at MIT, and was the director of the Sloan Laboratory for aircraft and automotive engineering from 1929 until his retirement in 1960.

His engineering books remain a primary reference for automotive engineers.

After retirement, he turned his attention to art, and his work is represented in several museums and public buildings throughout the United States.

Taylor’s sculpture, “Upward Bound” is 30 feet wide, and is suspended 17 feet above the ground. It is supported by steel cables and struts, and was fabricated from cylinders of brass which were welded together to create its larger forms.

According to a booklet published on the art in the Hurley Building, the upward-seeming movement of the sculpture is meant to symbolize the work of the building’s employees, who assist people in growing through economic and work opportunities.

The Hurley Building, as seen from the Boston Government Service Center’s courtyard. “Upward Bound”, a sculpture by Charles Fayette Taylor, can be partially seen at the right, within the building’s colonnade—and one can get an idea of the sculpture’s scale with respect to the complex’s overall design. © Image courtesy of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, photograph by G. E. Kidder Smith