A new video by DesignLAB architects features their work on the addition to the Paul Rudolph-designed Claire T. Carney Library at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth.

“GOD IS IN THE DETAILS” (AT LEAST IN RUDOPH’S DETAILS)

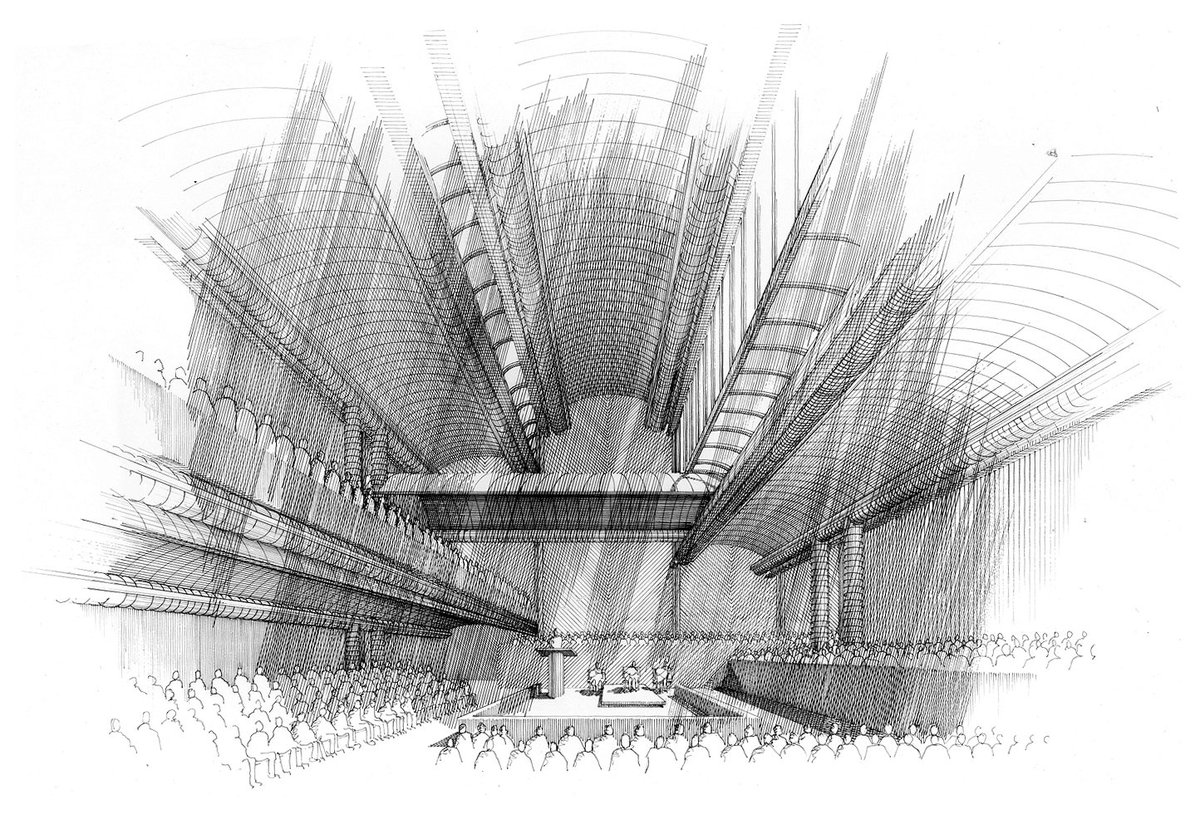

Spatial power: Paul Rudolph’s analytical drawing of his Tuskegee Chapel.

Image: Paul Rudolph Archive, Library of Congress – Prints and Photographs Division

Mies van der Rohe’s most famous saying is“God is in the details.” Of course, Mies was referring to the profound importance of carefully designed, well-considered, and fully-studied detailing in a building or object. Part of the criteria is not just whether a construction detail handles minimal practical needs (i.e.: “keep out the rain”)—but rather: the immense impact that even the smallest architectural details can have on the experience of a building (or an interior, or a piece of furniture.)

Does Mies’ exhortation about details actually have religious implications? And does it have such implications for Mies’ own architecture (and those practicing in a similar mode)? Those questions have been debated for a long time and are hard to answer, especially since Mies and other Modern architects have been relatively silent, or enigmatic, or maybe just un-committed about their spiritual inclinations.

When it comes to a spiritual interpretation of Mies’ famous saying, our best hypothesis is that Mies and his coterie believed that a superbly designed work-of-architecture (which, of course, would have very fine details) can bring forth experiences of transcendence: something akin to religious states. Well, that’s hardly to be wondered at, as such power is inherent in truly great works of art. Indeed, whether a work-of-art has that transcendence-inducing power (or not) is one of the ways we define its greatness (or lack thereof).Note well—and this is key—that we consider[some] architecture to be works-of-art, and hence open to this sort of assessment. We don’t know much about Paul Rudolph’s religious thoughts or feelings. He was the son of a minister, and Rudolph recounts that seeing his father engage with an architect (on a church that was to be built) was a key influence on his wanting to go into architecture. Some of Rudolph’s most interesting designs are for religious buildings—indeed, church, chapel, and synagogue projects punctuate his career. Here’s a drawing of a lesser-known project by him from 1956, a church for Siesta Key, Florida:

Rudolph’s perspective drawings of a design for the St. Boniface Episcopal Church, a 1956 project for Siesta Key, Florida. Image: Paul Rudolph Archive, Library of Congress – Prints and Photographs Division

And Rudolph’s Tuskegee Chapel truly helped anchor his fame:

The interior of Paul Rudolph’s Tuskegee Chapel, at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. It was constructed between 1967 and 1969, and is one of his half-dozen most well-known designs. Photo:G. E. Kidder Smith Image Collection, MIT Libraries

While Rudolph’s half-century career extended until his passing in 1997—and he was prolific to the end—his Cannon Chapel at Emory University, from 1975, was one of the last major non-residential works that he completed in the US:

Paul Rudolph’s Interior perspective-rendering of his Cannon Chapel, at Emory University. This commission may have been very meaningful to Rudolph: his father, Reverend Keener Rudolph, was in Emory theology school’s first graduating class. Image: This original pen & ink drawing is in the collection of Ernst Wagner, Founder of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Cannon Chapel features a prominent tower-like fin, whose major symbolic motif is a cross. But Rudolph’s approach is different: instead of the cross-as-object (which is typical of almost all church buildings), he renders that cross as cut-out of the fin’s stonework, creating a cross-shaped opening. So that cross, with the sun shining through, is an embodiment of light—a highly spiritual interpretation, in architectural form. Moreover, the light and shadow effect(on the building’s adjacent surfaces) is quite striking:

Part of the exterior of Emory’s Cannon Chapel. Image: Emory University

Even though the building’s primary symbolism is Christian, the building is used by a quite diverse range of the campus’ religious groups. Here’s a passage, describing that, from a 2001 issue of Emory Magazine: an article titled “Cannon Chapel: Twenty Years of Shared Sacred Space.”

Cannon Chapel is the center of religious observances on campus for a variety of denominations and religious groups. About fifteen hundred students attend official worship services each month. “Emory claims grounding in a faith tradition, and religious and spiritual life remains a foundational root of the University,” Henry-Crowe says. “And it is appreciated.” In any given week the chapel’s sanctuary, which seats 480, might be host to an ecumenical worship service, a Roman Catholic mass, an Emory Zen Buddhist group meditation, and a Jewish High Holy Days service. “We have diversity within diversity,” Henry-Crowe says of the thirty religious groups represented on Emory’s Interfaith Council. “The genius of the building is that it is built to be an interfaith space. No symbols are immovable.”

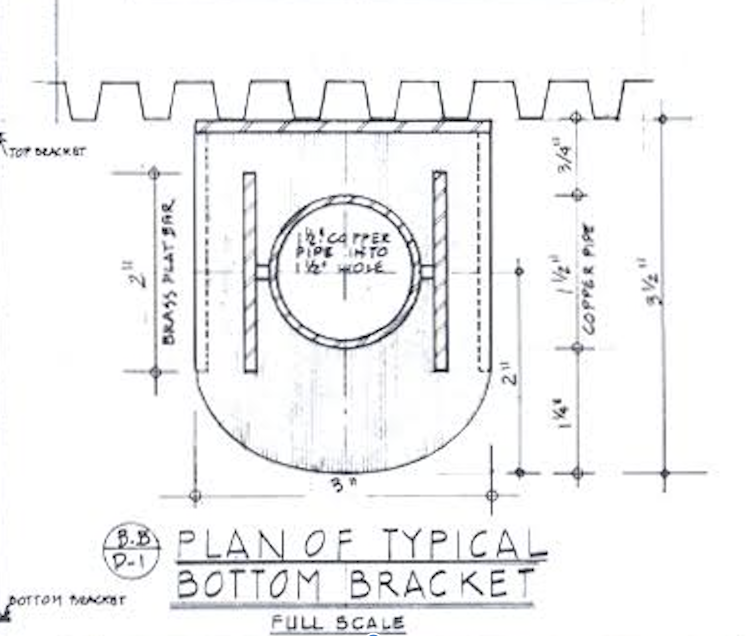

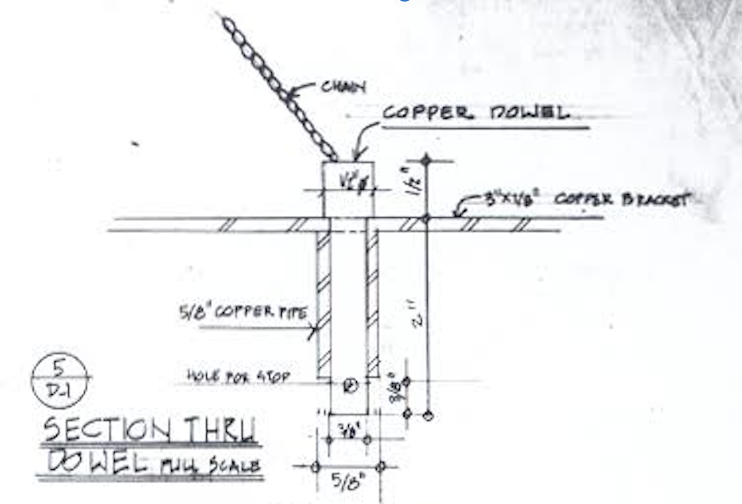

This is not the only case of one building being able to serve various religious groups—indeed, there is a study of how such religious space-sharing can work (and the accommodations that need to be made, to try to have that succeed). Apropos this, for Emory’s Cannon Chapel, it’s that article’s last line which intrigues us: “No symbols are immovable.” What’s that about? It turns out that the reference is quite literal. In the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, we came across an interesting construction detail [a godly detail?] This is a sheet from the construction drawings of Rudolph’s Cannon Chapel:

Construction detail drawing, from the set of drawings done by Paul Rudolph and his office for the Cannon Chapel at Emory University. This drawing, sheet number D-1, is dated 1981, and the title is: “Portable Cross & Portable Menorah Details.” [And below are some close-up views of portions of this drawing.]

Image: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

As you can see in the details shown above, flexibility was built into Emory’s Cannon Chapel, so that it could be used by various denominations.

While the ability to change key symbolic elements (in a shared sacred structure) is a good idea, it takes serious thinking to determine how that’s to be carried out: it’s not easy to design that kind of flexibility and have it be simultaneously buildable, fit within the budget, and ongoingly practical to use. Here, at Emory, it shows that Rudolph really cared about those details.