ABUNDANT COVERAGE

Paul Rudolph’s design for the Boston Government Service Center received attention from the architectural press, with articles about it appearing in Progressive Architecture (US), Architecture and Urbanism and Global Architecture (Japan), Architecture D’Aujourd’hui (France), Architectural Review (England), Architecttura and Casabella (Italy), and Deutsche Bauzeitung and Werk (Germany)—and some of these journals covered the project in multiple issues.

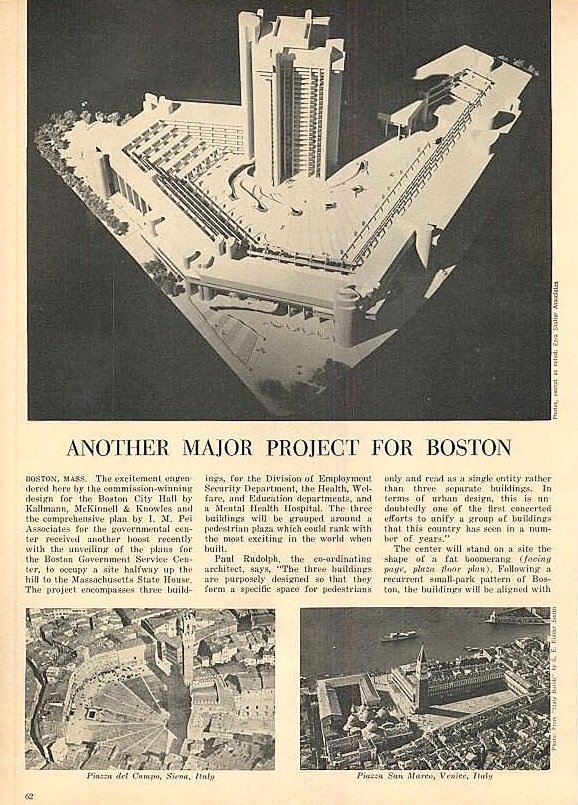

The February, 1964 issue of Progressive Architecture had several pages on the proposed design for the Boston Government Service Center. The main image on the first page (of the three devoted to the project) had a photo looking down into on a model of the complex, whose buildings enclose a pedestrian plaza—and on the same page are included intriguing comparison photos of plazas in Sienna and Venice. The subsequent pages show a large, detailed site/paving plan, side views of the model, and additional text. [Interestingly, this same issue’s main feature was Rudolph’s recently completed Yale Art & Architecture Building—to which they gave in-depth coverage.] Image courtesy USModernist Library.

In addition, the Boston Government Service Center appeared in numerous books around the time the building opened. Even later, it continued to attract attention—appearing in MoMA’s 1979 exhibit, Transformations in Modern Architecture (and being prominently shown in the catalog).

The Museum of Modern Art’s comprehensive exhibit, Transformations in Modern Architecture, was curated by Arthur Drexler (who also wrote the catalog), and opened in 1979. It displayed examples, from the previous two decades, of Modern architecture from around-the-world,—and sought assess architecture’s state and categorize its various pathways.

Several hundred buildings were shown in the exhibit and catalog, almost all with a single photo. But Paul Rudolph’s Boston Government Service Center was one of the few projects which was illustrated with multiple images (as shown in this scan of a page of the exhibit’s catalog.) A copy of the catalog is in the PRHF Library.

A DIFFERENT APPROACH TO THE BUILDING: “SPATIAL SYMBOLISM”

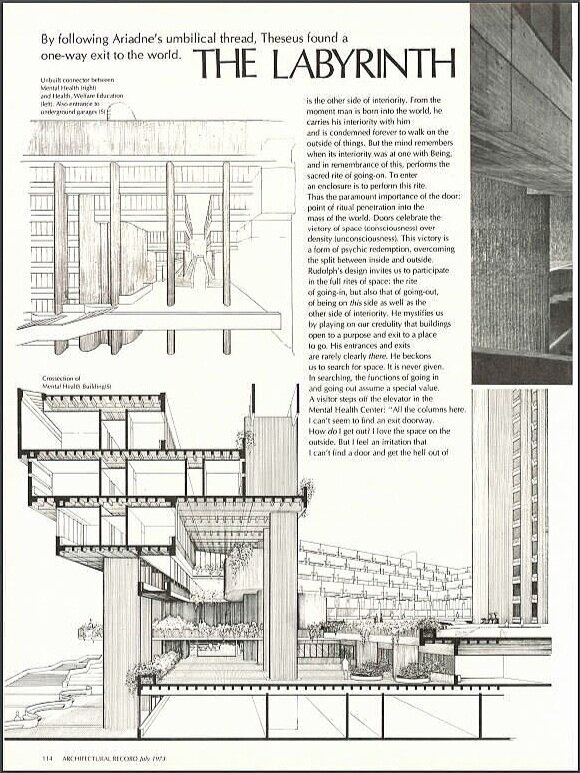

Architectural Record had several articles devoted to the complex—but none more interesting than when they made it the cover story for their July 1973 issue.

Their article was not the standard information package which architecture magazine readers usually expect in articles about new buildings—the typical collection of presentation renderings, plans and elevations, bookended by some descriptive text and credits. [In fact, the magazine had already done such an article about the complex in March, 1964.]

The new article was unique in several ways: it was 12 pages long, an unusually large amount of page space to devote to a single project; it was not by an architectural writer, but rather by a humanist scholar; and it did not have a primary focus on the standard functional requirements which a building is asked to fulfill, but rather attempted a deeper look into the building’s “spatial symbolism”.

Mildred Schmertz, a senior editor at Architectural Record, introduced it this way:

“Most of today's architectural critics write about space as total abstraction. They have little to say about its symbolic values, about space as a felt experience. When architectural writers talk about form and space, they speak in term s of solids and voids, vertical thrusts, intersecting planes, juxtapositions of scale, symmetry and other formal concern s. Interpretation for human meaning is ignored . . . Carl John Black, a young humanist, critic and teacher, formerly faculty member in the School for Humanities and Social Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and in the Division of Languages and Literature at Bard College, has never had formal training in architecture or the history of architecture. Nevertheless, he sees Rudolph's work as especially rich in symbolic content and feels that the conceptual drawings provide a key to the architect's spatial symbolism. Black has collected and assembled Rudolph 's drawings over the last several years for his forthcoming book Human Space: Conceptions and Constructions of Paul Rudolph . . .”

And so, as Mildred Schmertz explained,

“Because Black's insights deepen one's comprehension of Rudolph's work and his interpretations seem so very fresh to us, we have decided to publish an excerpt. . .”

A VISION OF HUMAN SPACE

This was not the typical article one would find in professional journals—but perhaps it did resonate with cultural concerns that were being discussed in the late-60’s/early-70’s: ones that embraced “alternative ways of knowing”. That’s an approach which might have appealed to Paul Rudolph, who rejected the unrelenting mechanistic/functionalist approach of his Modernist teachers.

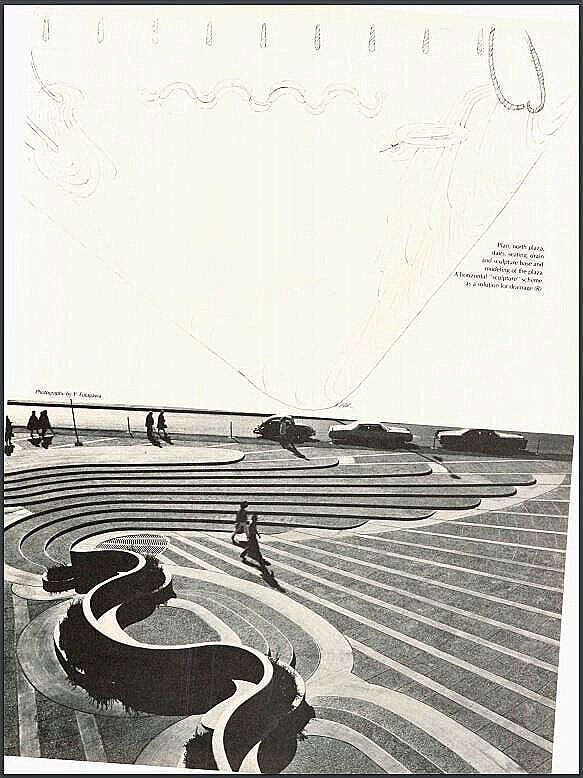

The article was illustrated with sketches by Rudolph, along with as-built photographs and perspective renderings, and was divided into:

SPATIAL ARCHETYPES

THE CONCH

SEA AND SHELLS

EBB AND FLOW

THE SPIRAL

THE LABYRINTH

THE CAVE

Below are scans of the full article. Access to a larger-scale version can be found here.

Mimi Lobell’s book, Spatial Archetypes, explores a similar approach to analyzing patterns of human settlement and architecture.

MEANING IN BUILDINGS: PRECEDENTS AND SUCCESSORS

Carl Black was not the only one exploring this path of examining architecture—one which looks at a building more deeply than just its surface functions. This approach has both precedents and successors—and it’s worth knowing about others doing this kind of analysis. Two distinguished architectural analysts, working in this direction, were:

William Jordy (1917–1997), an architectural historian (who was an almost exact contemporary of Rudolph), wrote American Buildings and Their Architects: Progressive and Academic Ideals at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Published in the early 1970’s, it examined key buildings for both their functional, technical, stylistic, and and symbolic importance.

Mimi Lobell (1942-2001), an architect and cultural historian, wrote a landmark study of the patterns of design, as applied to cities, land use, and architecture: Spatial Archetypes.

A TANTALIZING MYSTERY

Timothy M. Rohan, in his comprehensive monograph on Rudolph, tells us that Carl Black’s article (and the book of which it was to be a part) was part of an effort, by Rudolph, to share his ideas:

“…Rudolph clearly recognized theory's importance for the 1970s. He attempted to catch up with his younger colleagues by summarizing his ideas in what he intended to be a theoretical book, with a text by his friend Carl Black. Though the text was completed, the book was never published…”

This is a mystery worth pursuing. Was Carl Black’s book indeed finished?—and if so: where is the complete manuscript? Thus far, we have not heard of a copy of it in any archive. If you have any information on this, please let us know at: office@paulrudolphheritagefoundation.org

ACCESSING THE FULL ARTICLE

Here’s a direct link for the issue of Architectural Record which has the article on Rudolph and the Boston Government Service Center.

That issue of Architectural Record (July, 1973, Volume 154, No. 1) was one of the richest they ever published—“richest” with regard to the diversity and quality of the projects it showed. Not only did it feature the Boston Government Service Center, it also included: a portfolio of work by an architect who was on his way to becoming rather famous (Richard Meier); the home of Warren Platner (the designer of Windows on the World); a selection of church designs (one of which, by Russell Gibson von Dohlen, had a geometry of severe elegance); and a full article on SOM’s One Liberty Plaza (one of their most muscular skyscrapers.