The many faces of Mies van Der Rohe (1886-1969), the eminent (and eminently photographable) master of Modern architecture. This is a selection of portraits of Mies—just a few of many—as shown in this screen shot of a page of Google’s images.

We’re often asked:

Which architects, among Paul Rudolph’s contemporaries, did Rudolph admire?

and:

What architects influenced Rudolph?

The first question presents a bit of a problem. Rudolph, in his writings, speaks admiringly of the various “modern masters”—founders of the Modern Movement in architecture, like Wright and Le Corbusier—but he rarely refers to individual members of his own or later generations of architects. He sometimes decrys the inadequacies of contemporary practice, but would not indict—by name—the perpetrators. Nor can you find much explicit praise for his contemporaries. While not gregarious, Rudolph had the capacity to be gracious and friendly—but he was, by his own admission, highly opinionated (a “tough grader”). So perhaps it was out of some sense of tactical diplomacy that he didn’t often acknowledge individual contemporaries—good or bad, as he might have truly judged them.

The second question is is easier to answer. Rudolph attended Harvard’s architecture school in the 1940’s, and Walter Gropius—the head of the program—was a formative teacher there. While anybody looking at Rudolph’s work would say that he repudiated Gropius, Rudolph always spoke of him with respect. Rudolph’s admiration comes though for the other “Modern masters”, and he said:

“I would go around the world to see a Corbu building…”

Rudolph had met Le Corbusier (and, during the visit, received a gift: a carved sculpture of Corb’s “Open Hand” monument design).

A wall showing some of the “collections” within the Modulightor Building in New York. A painted wooden model of Le Corbusier’s “Open Hand” monument can be seen at the far-left. It was a gift from Corbuser to Rudolph. Detail of a photo © Annie Schlechter, Archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

One can see the influence of Le Corbusier on Paul Rudolph in numerous works. The exterior form of Corbusier’s Notre Dame is reprised in Rudolph’’s Tuskegee Chapel; and—in numerous other projects—Rudolph’s bold, sculptural use of concrete is aligned with the work which Corbusier was doing in that medium.

The young Rudolph (left), visiting a Frank Lloyd Wright building: the Annie Pfeiffer Chapel at Florida Southern University. Earlier, Rudolph had visited a home designed by Wright (the Rosenbaum House, in Alabama), and he repeatedly spoke about how influential were his experiences of Wright’s work. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

But for the fullest expression of admiration, one turn must turn to Rudolph’s remarks on Wright—of which this is an example:

"There are very few architects whose work I would go out of my way to see, but I would always go to see anything, even the worst, of Wright’s. . . . I regard him as the greatest American architect. I think he is, to a large degree. if not misunderstood, at least the implications of his work have not even begun to be explored . . .”

[For additional remarks by Rudolph on Wright, see our post which has an extensive collection of Rudolph quotes. And among our many post articles, you can also read a number that directly focus on Rudolph’s personal or architectural relationships with several of architecture’s “Modern Masters” and his contemporaries—including Wright, Mies, Gropius, Tigerman, the Metabolists, Benjamin Thompson, and Philip Johnson.]

A snapshot of Mies van der Rohe, when he visited Yale in the late 1950’s (at the invitation of Rudolph, when he was chair of the architecture school). We contend that’s Rudolph’s tweed-jacket enclosed arm (and sliver of forehead), emerging from the left edge of the image. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Previous posts have addressed the intersection of Rudolph and Mies van der Rohe—and it is to Mies that we return here.

This is prompted by our study of a conversation between Paul Rudolph and an old associate of his, which took place about a year before Rudolph passed away. His chat was with Peter Blake (1920-2006)—architect, writer, and editor of architectural magazines. Blake was on-staff at Architectural Forum starting from 1950, and was its editor-in-chief from 1965-to-1972—a period when Rudolph was at a productive peak and creating some of his most interesting works. He and Rudolph were almost the same age, and were long-time friends.

The conversation covers a variety of topics, and one gets a deeper insight into Rudolph’s thinking than from many other writings by or about him. In their conversation, Peter Blake asks Paul Rudolph about the several constituents of architecture, which Rudolph had listed in his writings and speeches (site, space, scale…) This ultimately brings them into speaking of Mies and a profound consideration of Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion.

An exterior photo and plan of Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion. It was the German pavilion at a world’s fair held in Spain in 1929, and was demolished at the end of the fair. This photo is part of the small set of well-known images of the building, as shown in the Museum of Modern Art’s 1932 exhibit and catalog, “The International Style” (curated, edited, and written by by Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson—both of whom Rudolph would come to know.) The Barcelona Pavilion became world-famous, and is listed among the top icons of Modernism—but, until it was re-built in the 1980’s, the only way to experience it was through the plan and a handful of black & white photos like the one above (which were endlessly reproduced).

The Barcelona Pavilion had been erected, to Mies van der Rohe’s design, as the German pavilion at a world’s fair held in in Spain in 1929—and was demolished shortly thereafter. Though it was short-lived, the building achieved world-wide status as one of the exemplars of Modern architecture (and the International Style.)

For decades, the idea of re-erecting it had been floated—and even Mies thought it wasn’t a bad idea. Mies passed away in 1969, and it wasn’t until the 1980’s that the Barcelona Pavilion was rebuilt.

A photo of the Barcelona Pavilion, as rebuilt in the 1980’s. Rudolph visited it—and it had a profound effect on him. Photo courtesy of Ashley Pomeroy at English Wikipedia

Paul Rudolph visited the rebuilt icon—and it affected him deeply, as shown in the following excerpt from his conversation with Peter Blake.

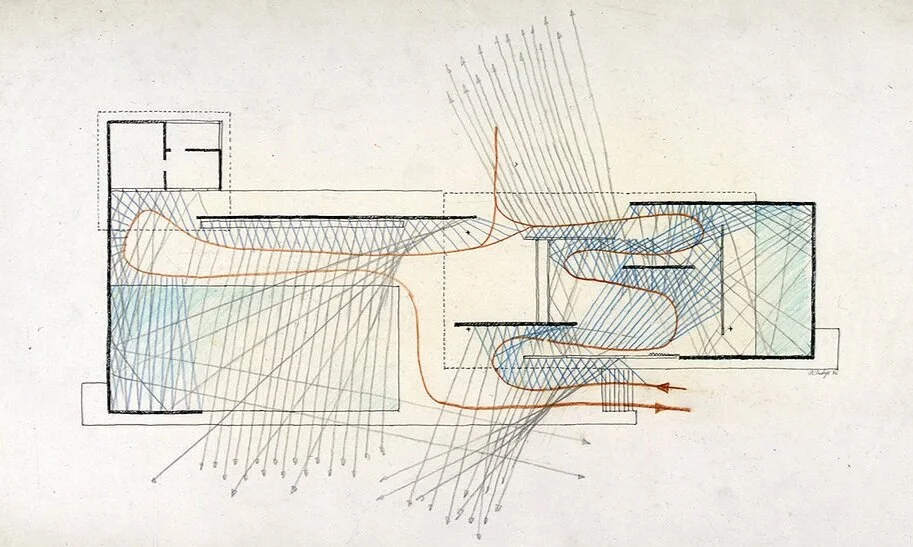

Note: Rudolph made a number of analytical drawings of the Barcelona Pavilion’s plan, to illustrate his points, and they’re inserted below.

Blake: So there we have it: site, space, scale, structure, function, and spirit. Have you noticed every time you talk about one of those things, you seem to touch upon or refer to Mies' Barcelona Pavilion in one way or another? Why is that?

Paul Rudolph: To me, the Barcelona Pavilion is Mies' greatest building. It is one of the most human buildings I can think of—a rarity in the twentieth century. It is really fascinating to me to see the tentative nature of the Barcelona Pavilion. I am glad that Mies really wasn't able to make up his mind about a lot of things—alignments in the marble panels, or the mullions, or the joints in the paving. Nothing quite lines up, all for very good reasons. It really humanizes the building.

Blake: My guess is if he had had a chance to redesign it about twenty years later, he might have messed it up—made it too regular, aligned everything....Paul Rudolph: Possibly. The courtyards and the interior space cast a spell on you which you will remember forever.

Blake: If you were to put your finger on it, what do you think you learned from the Barcelona Pavilion?

Paul Rudolph: I made a few sketches that are meant to illustrate the impact of the actual building [as rebuilt in 1992 on the same site as the original 1929 Pavilion], which is very different from drawings, photos, etc. The Barcelona Pavilion is religious in its nature and is primarily a spatial experience. We have no accepted way of indicating space, and therefore the sketches made are very inadequate. One is drawn by the sequence of space through it. Multiple reflections of the twentieth century modify the architecture of light and shadow in a manner that no other building can equal. Twentieth-century concepts have affected all of the past. Reflections are organized so that shadows are lit and become a spatial ornamentation for the whole. These shadows and reflections are most intense at crucial junctures, such as the principal entrances, or turning points in the circulation. For instance, a forest is created via reflections and refractions in the marble and glass surrounding you. This multiplicity of reflections unites the exterior and interior but also helps to explain the mystery of the whole. I think it is simply unprecedented in architecture and the greatest of all of Mies' buildings.

Blake: Your first drawing is a series of diagrams showing the circulation through the building. On the east is the more familiar entrance, used by the general public; on the west is the entrance for the King and Queen of Spain and used by other dignitaries at the time of the opening.

‘Density & Flowing Of Space’ - Paul Rudolph’s graphic analysis of Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Paul Rudolph: Yes. The circulation from the east leads you up a flight of steps that leads to the platform on which the Pavilion stands. This flight of stairs is spatially compressed, and when you reach the top of the platform, the pool causes you to turn 180 degrees. This turn prepares you for the compressed entry with a glass wall on the right and the green Tinian marble wall on the left, all modified by reflected trees. This squeezed space leads directly into the larger dominating space that contains the major function of the Pavilion. This flow of space continues all the way through the building in a highly disciplined way; nothing is left to chance. In my diagram the compressed space, the liberated space, the movement of space diagonally, vertically, and curved space modify the rectangular plan in a very clear and surprising fashion. The space is revealed but also hidden. The density of space is greater as it approaches the defining planes that form the Pavilion. This inward pull to the defining planes is offset by the reflective surfaces, so that most of the surfaces vibrate. I have tried to define the essential fluidity of these spaces and the interconnection of the inside and the outside. This highly disciplined flow of space is all-pervasive a natural constriction and release of space that leads you on, on, on; everything is in motion, and you are carried along almost by unseen but felt forces.

Blake: How does it work?

Paul Rudolph: The space becomes more dense the closer it comes to the walls and more fluid as it approaches the center. My second drawing is an attempt to illustrate this. The diagram indicates the way one follows the prescribed path in and out of the building. The angle of vision as it meets the wall surfaces is similar to the angle of reflection. Byzantine structures, with their curved and reflective surfaces, approached the same effect, but this is very different because the universe is also reflected. Reflections in the Barcelona Pavilion augment and embellish the spatial organization and never contradict the thrust of the whole, for it is integral to the whole.

‘Circulation & Reflection From Walls’ - Paul Rudolph’s graphic analysis of Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Blake: Your third drawing describes the circulation through the Pavilion in still another way.

‘Circulation & Cone Of Vision’ - Paul Rudolph’s graphic analysis of Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Paul Rudolph: The dots represent various natural places where you might pause, where you might stop, and turn, and look around. Everyone sees the world through a 22.5 degree cone of vision around a horizontal line about five feet four inches above the ground. I think Mies studied these angles of vision very carefully. Nothing has been left to chance, for at each turn the clarity of composition remains composed and its fluidity and its interrelationships remain intact. By the way, the importance of the 22.5 degree of the angle of vision as a method of organizing and moving through space is not really a twentieth-century discovery. The Acropolis, I believe, was organized much in the same way, for it utilized the universal angle of vision, lending coherence to the elaborate and unparalleled organization of its sequence of space. In fact, I think the organization of great European urban spaces show that this angle of vision must have been understood....

Blake: Did you ever talk to Mies about these things?

Paul Rudolph: No, but I believe that the reason the Barcelona Pavilion seems so serene, so logical, so peaceful, so spiritual is due to Mies' interest in movement, in space, in his interlocking spaces and his analysis of seeing.

Blake: In your fourth drawing you seem to have concentrated on the ends of walls, the sharp edges that are a characteristic of a freestanding wall panel of the sort employed by Mies in this Pavilion. What are you trying to say?

‘Architectural Space As Modified By Transparent Planes’ - Paul Rudolph’s graphic analysis of Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Paul Rudolph: The revealed ends of the walls, the edges, are a method of leading you in a very logical way to investigate what is behind and beyond this screen. It also celebrates the clarity of structure juxtaposed with a non-load-bearing wall or screen. The idea that is implied in all these spaces in the Barcelona Pavilion is one of the reasons for its power. The sketch suggests that curved space and diagonal space is implied in spite of the literal geometry. The seemingly haphazard arrangement of divisions of space in the building follows a very consistent pattern. Planes in space—as opposed to the traditional walls with holes for light and access cut into them—make clear the essential method of twentieth-century building. However, planes in space at the Pavilion are spatially much more important, because the mirror-like finish of the columns reflects what is near, and columns do not count for very much.

Blake: It seems to me that you are always conscious of another space and then another beyond those walls and that you are drawn from one to the next.

Paul Rudolph: I should say that all these things are related one to the other. The invisible, diagonal, radiating planes from the ends of the walls—planes that don't really exist at all but are implied everywhere—are a profound contribution to the spatial fluidity of the Pavilion.

Blake: Another aspect that seems to play a significant role is that you keep picking up reflections of that Kolbe sculpture—the image keeps being reflected in unexpected and surprising ways.

Paul Rudolph: I really wanted to make a drawing from the location of the sculpture, indicating the Pavilion as seen from that point—as if I were standing there. The whole notion of the placement and power of that sculpture is a pro-found mystery to me. Although the sculpture's placement is not the best, I think I know some of the reasons Mies placed it where he did; but I have never gotten it all down on paper.

Blake: What makes that sculpture so important in your eyes?

PR: It is the point where the whole Barcelona Pavilion becomes most clear. If you were the sculpture and you were looking south from that location and east, you would become aware of all the largest dimensions of space in the building and the terraces and beyond. You would be seeing the layers of transparency and translucency, reflections of the unseen and seen, and implied space presented in multiple ways. And the sculpture would be seen simultaneously, implying movement of a different order. If you stood where that sculpture stands, you would have that multiple view of things all around you—the view the cubists always talked about.

Blake: And conversely, of course, there is hardly a place on the platform that the Pavilion sits on that doesn't offer a glimpse of that sculpture. So it becomes an ever present reference point as you walk around in the Pavilion and on the terraces.

Paul Rudolph: Yes, the sculpture seems literally to move. And one reason is the placement, although the sculpture is often hidden in actuality and visible only in reflections. It is very much with you all the time, even though it stands in its own private space, where not even fools can tread. It is a kind of focal point, but not in the usual sense. It is given new life by the Pavilion itself. The dialogue between the sculpture and the building is unlike any other dialogue between a work of art and a building that I know of. It is one of the few times a sculpture has been used as an integral part of the whole, and this gives the sculpture added meaning.

Blake: When you saw the Barcelona Pavilion for the first time—in reality, not in photographs—was it at all as you expected it to be?

‘Circular Flow Of Space At Ends Of Panels’ - Paul Rudolph’s graphic analysis of Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion.Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Paul Rudolph: The reality of the Pavilion, to me, is totally unlike what I expected it to be after seeing all those photographs, models, and drawings, for it demonstrates the inadequacy of our studies. I expected it to be a composition of rectangles and minor and major axes, but it isn't that way at all. It is very fluid, and the space moves in ways that are difficult to imagine.... My diagrams suggest a circular motion around the ends of the walls. That may be one way of describing it. In my opinion, the columns, which all of us thought were so important, stand for almost nothing, for they reflect their environment. When I first saw the various drawings and photographs, I thought the columns were the organizing factor of the Pavilion because of the reflective nature of the chromium-plated steel .... But they are almost negligible. The lustrous power of those marble walls—they are almost like paintings in space, especially those onyx Tinian marble slabs. The walls of marble and glass and the imagined diagonal planes really shape the spaces in the building.

Blake: Your fifth drawing deals primarily with light and shade.

‘Space As Modified By Light’ - Paul Rudolph’s graphic analysis of Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Paul Rudolph: The relationship of light and shadow and reflections seems to change constantly. And there is no glare in the Barcelona Pavilion at all. The reflections of bright Spanish sunlight from the marble walls and from the Travertine floors onto the ceiling, all of that balances the light and eliminates glare.

Blake: Is the ceiling lit primarily by reflection from the pools?

PR: Not only from the pools. Most of the reflection is from the marble floors. Except, of course, there is that black rug in the main area of the Pavilion. I had never understood the importance of that black rug until I actually saw it.

Blake: What exactly is its importance?

Paul Rudolph: It is the center, the focus of the Pavilion. It is like the inglenook in a Frank Lloyd Wright house or in a medieval castle. It is the most intense and most emphatic center—and it is just created by a simple black rug! It is the antithesis of the reflective marble flooring. It is like a black hole; it picks up no light. The Barcelona Pavilion is a study in the handling of natural light. Really unparalleled, I think. Mies' understanding of light and shade and tonalities was really profound.

Blake: Are there no skylights in the Pavilion's first roof?

PR: I often wondered why there were no skylights. In a sense there are, of course—the space above the small pool, for example, and the space between the outer walls and the glass walls that form the actual enclosure. Mies did not want to make a window, needless to say. I once tried to find a way of improving the Pavilion by inserting skylights. It was totally wrong, of course. He was trying to emphasize the power of that black rug at the center and to reach for light as the space reaches out toward the perimeter of the Pavilion. If he had introduced light at the darkest point, in the center of the Pavilion, he would have deprived the space of that sense of protection in the one place where he wanted it passionately. So again, Mies was right.

Blake: Is there any one thing about the Barcelona Pavilion that you feel affected you most profoundly in your work?

‘Horizontal Space - Longitudinal And Transverse Flow’ - Paul Rudolph’s graphic analysis of Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Paul Rudolph: Well, I am influenced by everything I see, hear, feel, smell, touch, and so on. The Barcelona Pavilion affected me emotionally. It is one of the great works of art of all time. I could not understand at first why it affected me as it did. I never really liked the outside of it. But the inside of the Pavilion transports you to another world, a more spiritual world. By the way, you realize what you are doing, don't you? The two things you are getting out of me are the twentieth-century brick and the Barcelona Pavilion. People are going to think I am half mad!

Blake: I very much doubt it. Let's go out and have some lunch.

[A transcription of their entire conversation is in Paul Rudolph: The Late Work.]

The complete conversation between Paul Rudolph and Peter Blake—in which Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion is extensively discussed—is in this important volume on Rudolph’s oeuvre. Roberto de Alba’s book covers work from the final phases of Rudolph’s half-century career, and projects were selected with the architect’s input.

It is becoming a rare book—but, fortunately, copies are still available from the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation HERE.