Leveraging the Landmarks

Development Whitepaper

Margery Perlmutter - Spring, 2025

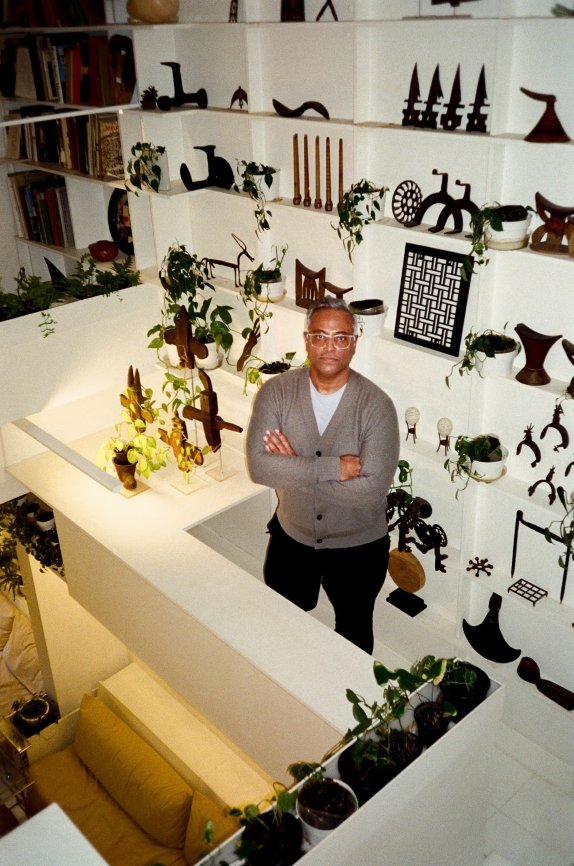

Photo by Joe Polowczuk

One small but very important new provision in the City of Yes zoning text amendment, approved last December by the New York City Council, will finally enable owners of New York City’s individual landmark buildings to realize more of the site’s economic potential by tapping into new income opportunities to facilitate essential building maintenance and restoration.

Historic preservation aims to protect the historic character of the built environment, ensuring the architectural and cultural history of the city is not destroyed in the wake of modern development. The New York City Landmarks Law (NYC Admin Code. Title 25, ch. 3), which created the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, sets the parameters for designation of historic properties. The Commission has the power to designate for protection individual historically significant buildings, historic districts, scenic landmarks and interior landmarks. According to LPC’s website, «there are more than 38,000 landmark properties in New York City, most of which are located in 157 historic districts and historic district extensions in all five boroughs. The total number of protected sites also includes 1,464 individual landmarks, 123 interior landmarks, and 12 scenic landmarks.» Typically, scenic sites are public parks, including Central Park and Prospect Park, while interior landmarks are spaces that are accessible to the general public, such as lobbies and public buildings.

Once a property has been designated, the extent to which a building, a building’s interior or a scenic site may be modified is governed by the Landmarks Law and the Landmarks Rules (RCNY Title 63) and will require at minimum permission from LPC staff to make such modifications. More significant modifications require approvals from a majority of the LPC’s eleven commissioners after presentation of the proposal to the local community board and at LPC public hearings and meetings. Typically, existing buildings within historic districts are allowed more latitude to make visible changes, such as rooftop enlargements or facade modifications, than are individual landmarks. Individual landmarks are subject to strict review and few visible exterior modifications are permitted to them because generally the designation of the property as an individual landmark is based on its individual and special, often unique, historical, cultural or architectural contributions as compared to collections of buildings found within historic districts. Such individual landmarks may be the grandest examples we have of a particular style, period, architect, cultural phenomena or owner. The Beaux Arts 42nd Street public library designed by Carrère & Hastings, or the mid-Century modernist TWA terminal at JFK by Eero Saarinen are two great examples of individual landmarks that include designated interior landmarks.

However, of the 1,464 individual landmarks, there are many buildings that are held or operated by not-for-profit organizations that depend on donations and endowments to support their missions and maintain their facilities. Caring for a landmark building can be more costly than caring for a non-landmark, since the integrity of the landmark’s historic character requires sensitive and faithful attention to the building’s original design, form, materials and detail.

Often repairs, restoration, replacement of more significant building elements when needed to maintain the building’s structural integrity, or permitted enlargements will demand the work of expertly skilled design and restoration architects, technicians and contractors. As stewards of these important individual landmark buildings, the not-for-profit owner is faced with the dilemma of fundraising to support two essential missions: their cultural, educational or religious purpose and the enduring tangible memory of that purpose embodied in their carefully preserved landmarked building.

And one might ask, why should a not-for-profit take on the additional burden of caring for a costly individual landmark? Often, however, the identity of the organization is tied directly to its relationship to the building itself. Take, for example, the many private clubs in New York City that were built either as homes for a founding member or built expressly by the club by a notable architect. The University Club and the Metropolitan Clubs on Fifth Avenue, are two such individual landmarks. Museums, such as the Guggenheim and Frick Museums, are another typical example of expressly built buildings of grand, important design that have been designated as individual landmarks. Houses of worship, many of which are great buildings designed by important architects expressly to fulfill the needs of the congregation they serve, are yet another example, such as Saint Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue or Saint Bartholomew’s on Park. The West Park Presbyterian Church on West 86th Street and Columbus Avenue is one house of worship now suffering from its inability to afford to maintain its neglected Romanesque Revival individual landmark building and, at least its tenants are looking to neighborhood celebrities to come to the rescue.

City of Yes, NYC Zoning Resolution (ZR) Section 75-42 is here to save the day! Hopefully.

Sitting on a 10,157sf zoning lot in a C1-5/R10A zoning district with only 16,003 sf built on its site, West Park Presbyterian is underbuilt by more than 85,000 sf. No wonder Church ownership argues that they cannot afford to restore the building and should be freed from landmarks designation so that it can sell the site to developers who will tear it down to build luxury housing in a choice Manhattan neighborhood.

Until last December, there was no other choice than that short of finding a benefactor.

Before the approval of City of Yes, an individual landmark that had excess air rights could only transfer them as of right to an adjacent property in the same zoning district, or with special approvals through a very expensive and elaborate special permit process requiring review by the City Council, the City’s Department of City Planning, the borough president and the community board. With this special permit, the individual landmark could only transfer these rights to an individual landmark could only transfer these rights to an immediately adjacent property in a different zoning district, or to one that is directly across the street from the landmark. This earlier process had been used only rarely and only to benefit large developments, such as the Museum Tower building adjacent to the Museum of Modern Art at 15 West 53rd Street in Manhattan, because navigating the complex Uniform Land Use Review Process, more commonly known as ULURP, as well as satisfying NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission mandates for the landmark, required well-heeled developers with teams of land use and real estate lawyers. Developers used this process when the amount of air rights were significant, leading to the construction of larger, taller buildings that translate into better views and higher sale prices.

For most individual landmark buildings under those now obsolete regulations, there were no receiving sites to which the landmark could transfer, and often, the buildings could not be enlarged to utilize their air rights themselves without compromising and even destroying the historic character that entitled them to such individual landmark status in the first place (one example is the University Club on Fifth Avenue at East 54th Street that supplied the air rights for the MoMA tower). With no receiving sites, these landmark buildings could not sell their air rights to support essential repair work.

ZR Section 75-42 addresses this issue by expanding the area into which an individual landmark can transfer its air rights. The text now allows such transfers to travel anywhere on the block on which the landmark is located and to lots located across the street and across the intersection from the subject block.

To reduce the bureaucratic red tape, the City of Yes changes the process by which such transfers are possible to a City Planning Chair ‘‘certification,’’ which is a non-ULURP process and is much less cumbersome.

To avoid over-development on a given receiving site and to respond in advance to community concerns, the amendment limits the amount of air rights that can be transferred to a single receiving site to not more than 20% above the maximum allowable floor area ratio (FAR) permitted as of right on the receiving lot. Consequently, where a landmark has a large quantity of air rights to sell, it would need to sell those rights to several sites within the allowable transfer zone. The only exception to the 20% limitation is for high-density commercial and manufacturing districts where the allowable FAR is 15.0 or greater, such as what one would find in certain parts of Midtown. In such cases, a receiving site could achieve an increase in floor area equal to 30% of its maximum allowable FAR. For increases higher than 30%, the more complex City Planning special permit under ZR Section 74-79 would be required. That same special permit can also be pursued to obtain modification to the ZR’s bulk regulations, such as height, setbacks and yards.

To ensure that the granting individual landmark site will indeed be maintained as a result of the transfer, ZR 75-42 requires that an LPC-approved «continuing maintenance» program is established. In addition to addressing the immediate repair needs of the landmark, the proceeds from the air rights sale will often be placed in an endowment fund, the interest income from which will be drawn for ongoing maintenance.

As an example, the Paul Rudolph Institute For Modern Architecture’s Modulightor Building on East 58th Street is a 6-story recently designated individual landmark on a 20 x 100 lot. It is located in a zoning district that allows 10 times the lot area of the lot and is using only half of that area for the landmark building. This leaves 10,000 square feet of air rights available for transfer. Under the pre-City of Yes zoning, it could transfer to only one immediately adjacent lot and none of the lots directly across the street from it were viable receiving sites. This situation gave the owner of that one adjacent lot unequal bargaining power in the potential air rights sale; hence it offered to acquire the air rights at far below market value. With the enlarged transfer / receiving area made possible by ZR 75-42, there would now be at least 14 potential receiving sites on the block on which the Modulightor is located. This number doesn’t even factor in the additional potential receiving sites located on the block frontages to the north, south, east, west and across intersections from Modulightor’s block. And, since the receiving sites may not accept more than 20% of the maximum allowable FAR permitted on each lot, the typical transfer would only represent a one-story enlargement to an existing building, a small but valuable addition for any owner. Of course, larger assembled sites within the permitted radius may be able to take on all of Modulightor’s excess development rights to incorporate into a new building without exceeding the 20% receiving cap.

The 20% increase in FAR to support historic preservation serves an important public policy purpose and is equivalent to existing and recently approved City of Yes regulations that allow a similar increase where affordable housing is provided.

Keeping the transferable amount small and non-controversial in most neighborhoods, allows for a simple approval process that would be affordable to both seller and buyer. This is a great first step that should encourage owners of individual landmark buildings and their neighbors to begin negotiations. It remains to be seen how many buyers will come forward to participate in this process and whether a 20% increase is enough to justify it.

Raising the 20% cap on maximum allowable FAR also is important because it will inspire private-sector investment in our communities and give property owners more options and flexibility while infusing landmarks with additional capital. The concept of a wide district of receiving sites saving landmarks is best represented by the zoning-incentivized renaissance of the Theater Sub-District in West Midtown. The world-renowned landmark theaters in the Theater District were saved because their owners were allowed to sell their air rights to commercial buildings located within the transfer zone, and the profits from these transfers paid for the restoration and ongoing maintenance of these fabulous historic buildings. Likewise, the East Midtown sub-district, approved in 2015, enables the transfer of development rights from individual landmarks, including Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, to receiving sites within specially designated sub-districts.

Giving landmark buildings greater ability to sell their development rights can generate billions of dollars in new economic activity and spur the creation of thousands of new jobs while continuing to preserve the built symbols of our City’s history. Cutting red tape and relaxing antiquated restrictions to spark economic growth is what the City of Yes was designed to accomplish.

The real estate and development community should begin now to leverage our landmarks to enhance development of new buildings and enlargements. This will in turn reinvigorate our communities with new business opportunities and support our non-profit institutions with real solutions for their very real problems.

Go to the original article here.