From Christmas Lights to Megastructures - Curator Abraham Thomas on Six Defining Works of Paul Rudolph’s Career

Pin-Up Magazine

Michael Bullock - March 06, 2025

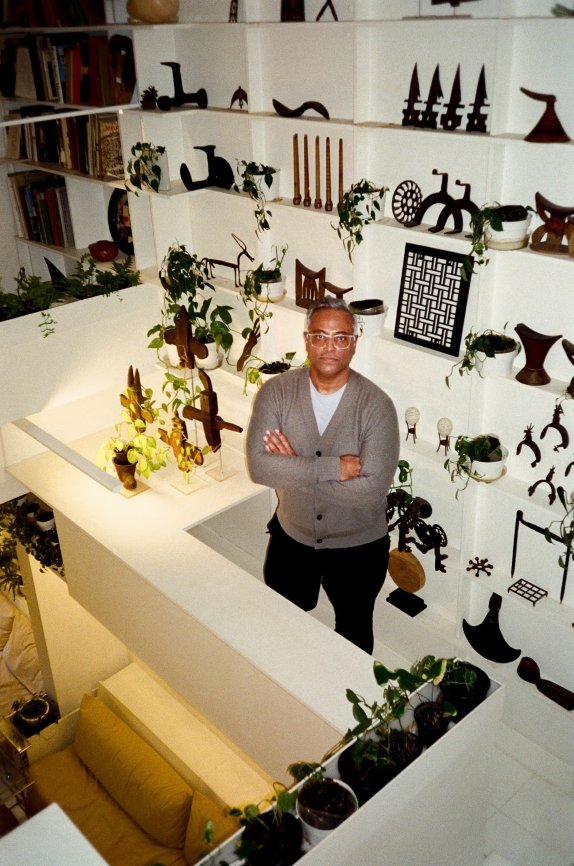

Curator Abraham Thomas, the Met’s Daniel Brodsky Curator of Modern Architecture, Design, and Decorative Arts, photographed inside the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture in Manhattan. Photographed by Matías Alvial for PIN–UP.

The trajectory of Paul Rudolph’s career is something of an enigma. Straight out of the gate in the late 1940s, after being mentored by Walter Gropius and outshining his Harvard classmates Philip Johnson and I. M. Pei, the Southern-born son of a preacher made his mark designing Modernist beach homes. By the mid-1960s, he had emerged as one of the world’s leading Brutalist architects, a master of concrete. In his hands, it was organic, textured, and soulful. He won coveted commissions, including the Yale Art and Architecture Building and the Burroughs-Wellcome Company Corporate Headquarters. He went on to pioneer a new type of public housing megastructure that appeared at once cavernous yet as intricate as origami. He famously told the media that he “preferred caves over fishbowls.” The press loved him, his peers revered him.

Then fashion changed. When Postmodernism entered the picture, Rudolph refused to follow. As commissions dwindled, he redirected his focus, scaling back his ambitions from entire cities to singular apartment interiors — though with no less bravado or innovation. Sidelined in the U.S. for the rest of his career, he reemerged in Asia decades later, where his large-scale work found a new audience. In the 1980s and 90s, he designed ambitious projects in Hong Kong, Jakarta, and Singapore.

Rudolph was a man with an unapologetically radical vision for society — one in which comprehensive, 2-mile-long systems of living, transportation, work, and leisure were seamlessly integrated into a single interconnected megastructure. His transformative architectural framework was so complete, articulate, and masterfully drawn, it is as captivating as it was polarizing — a sci-fi, cinematic future equally utopian and sinister.

Despite his remarkable achievements, in recent decades, the architect’s overarching legacy had all but faded from public view, with his contributions to interiors becoming his most widely recognized work. Rudolph, who openly lived with his partner while maintaining discretion in his professional life, holds particular significance within gay culture for designing some of the most notorious bachelor pads of all time. The Hirsch House, which became a Studio 54 after-hours venue when acquired by fashion designer Halston, stands as a prime example. Halston commissioned Rudolph to renovate it in 1974, and the low-slung, multi-tiered loft hosted Liza, Bianca, and Andy. Rudolph’s interior was the ultimate stage set of the 70s, an aesthetic that continues to shape pop culture’s imagination. It was rivaled only by the two projects he designed for himself. His Beekman Place penthouse was legendary for its psychedelic mylar and mirror opulence, featuring a voyeuristic glass-floored bathtub dramatically positioned above his desk in his office below. Later, this home-as-design-lab experiment evolved into his ground-up townhouse, the Modulightor Building (1989), headquarters for his innovative lighting design company.

Curator Abraham Thomas, the Met’s Daniel Brodsky Curator of Modern Architecture, Design, and Decorative Arts, photographed inside the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture in Manhattan. Photographed by Matías Alvial for PIN–UP.

In keeping with his rollercoaster career, it’s only fitting that, just as his legacy teetered on the brink of obscurity, Paul Rudolph is now reclaiming the spotlight. He becomes the first architect to receive a solo exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art since Marcel Breuer in 1972 — over fifty years ago. I met with the man responsible for righting this wrong: curator Abraham Thomas, the Met’s Daniel Brodsky Curator of Modern Architecture, Design, and Decorative Arts in the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art since 2020. His inaugural exhibition at the museum, Materialized Space, can be credited with restoring Rudolph to his rightful place in the architectural canon. I must say, I was so chuffed when the exhibition banner was unveiled on the front of the building,” Thomas admitted. “I mean, for Rudolph, yes — but also, in general, to have an architect's name on the Met’s façade is a big deal. A grand statement. And I’m hoping it’s just the first of many.” With that, he led me through the sixty works he selected, pausing to highlight six in particular. What followed was an enthusiastic mini-tour that captured the peaks and valleys of Rudolph’s practice — a career he himself once described as spanning “from Christmas lights to megastructures.”

Concrete Mold from Yale Art & Architecture Building (1962)

One of my favorite objects in the exhibition is this piece of wooden formwork from the construction of Paul Rudolph’s Yale Art & Architecture Building. I’ve always loved showcasing what I call the “messiness” of the architectural process — those rough, working objects that tell the story of how buildings actually come into being. This fragment does that beautifully. But what excites me even more is that it feels like an archaeological relic — something you’d expect to see elsewhere at The Met, pulled from a long-lost civilization. And yet, it’s from 1962, salvaged from the construction site of one of the most significant architectural projects in the U.S. We were fortunate to borrow it from the Yale School of Architecture, where it hangs in Andrew Benner’s office. I love that on the back, you can still see the name of the student who retrieved it from the site — there’s something so personal about that. Now it’s displayed in a vitrine, treated like a precious artifact, which is both charming and a little playful. Beyond its history, this object reveals Rudolph’s deep engagement with material and texture. His “corduroy concrete” façade at Yale is one of his most iconic achievements. Concrete was poured into molds like this, forming vertical fins, which were then bush-hammered by hand to expose the aggregate beneath. This labor-intensive process resulted in an extraordinarily rugged, textured facade — sculptural, expressive, and so tactile. You run your fingers across it, and you feel the effort, the precision, the time. That’s what I love about this piece: it’s humble, but it holds all those layers: craftsmanship, experimentation, and Rudolph’s daring vision. It captures the drama of his work and the beauty of process made visible.

Rudolph on Film

I thought it would be interesting to showcase various clips from films and TV shows that feature Rudolph’s buildings as locations. For example, in an early scene from the film Brainstorm (1983) starring Christopher Walken, you really get a sense of how one moves through these spaces. The film highlights that extraordinary concrete texture we discussed earlier, and it also reveals another technique Rudolph used: a pebble-dash effect that creates a consistent, expressive concrete surface. This film helps convey the incredible potential Rudolph saw in concrete, transforming it into expressive surfaces and dramatic volumes. Another favorite clip, taken from The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), perfectly captures the vertical transition in his Beekman Place apartment, illustrating the sensation of moving through that space. Shot shortly after his passing, it preserves the apartment as it was at that critical moment. The clips do more than just show the cinematic potential of Rudolph’s spaces; they hint at something deeper. Just like his drawings, they explore a realm of imagination that goes beyond what was actually built, and create a liminal space where Rudolph’s vision flourishes.

Lower Manhattan Expressway/City Corridor project (unbuilt), New York, ca. 1967

One of the most renowned drawings from this project is the perspective section of the Lower Manhattan Expressway from The Museum of Modern Art’s collection. For me, this drawing encapsulates everything Rudolph envisioned for his mammoth, city-scale urban planning projects — ambitious, often unrealized schemes that lie at the very core of his reputation. It reflects his determination to redefine urban landscapes, picking up the mantle from the controversial Robert Moses Manhattan Expressway project. As Rudolph himself put it at the time, rather than a highway, he was intent on building a piece of architecture 2 miles long.

Commissioned by the Ford Foundation, his proposal sought to address the chronic congestion in lower Manhattan. In doing so, Rudolph embraced what many regarded as the most villainous anti-urban scheme, yet he transformed it into a genuinely urban concept. His drawing examines issues such as urban density and the challenge of stitching together a coherent urban fabric along a path originally outlined by Moses — from a subterranean tunnel right up to the East River bridges. In his vision, the expressway runs beneath a pedestrian-level plaza designed to muffle the noise of traffic, while simultaneously integrating parking decks and intersecting with key mass transit nodes. Residential and retail functions are woven into the fabric of the design, suggesting a holistic approach to the urban public realm alongside essential infrastructure.

Curator Abraham Thomas, the Met’s Daniel Brodsky Curator of Modern Architecture, Design, and Decorative Arts, photographed inside the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture in Manhattan. Photographed by Matías Alvial for PIN–UP.

While many critics might argue that such a project would have utterly destroyed the historic character of Manhattan neighborhoods, this drawing remains a compelling commentary on the urgent need to address urban density by merging disparate functions into one unified scheme. It speaks to the sheer scale of ambition that defined Rudolph’s work — a pursuit that set him apart. Most of his peers were shocked by the proposals he boldly published. For me, this drawing was one of my primary entry points into understanding Rudolph’s genius; even though it has become nearly synonymous with the Robert Moses era. Moreover, it’s a vivid demonstration of Rudolph’s ability to merge functionality with a cinematic, almost dystopian vision. It is not merely a technical plan but an exploration of the full extent of his architectural imagination, rendered on paper with a masterful blend of precision and creative audacity. Every element — from the underlying expressway to the above-ground urban plaza — is depicted as part of a cohesive whole. This fusion of urban theory with bold visual expression continues to captivate and inspire, affirming Rudolph’s lasting impact on Modern architecture.

Burroughs-Wellcome Company Corporate Headquarters, North Carolina, 1969

One of the most striking drawings in the exhibition is the perspective section of the Burroughs-Wellcome Company Corporate Headquarters, a key example of Rudolph’s campus designs from the 1960s. This period marked the height of his career, with major projects at Yale, but Burroughs-Wellcome stands out not only for its architectural significance, but also for this spectacular drawing. Rudolph devotes nearly two-thirds of the composition to the surrounding landscape, making the building feel almost like an alien form dropped into the untouched North Carolina terrain. His attention to texture extends beyond the structure to the dense tree line. The drawing, though less famous than his Yale perspective section, is a masterclass in combining perspective and section to create an immersive sense of spatial organization. Moving closer, you notice how he meticulously renders the central spine: this is where Christopher Walken was seen carrying his bicycle in Brainstorm. His detailing brings the space to life, from the textured concrete to the signature orange carpeting and slanted trapezoidal forms. His deep interest in shadow and light is evident, showing how architectural elements interact dynamically throughout the day. Rudolph often spoke of “architectural energy,” and his drawings emphasized movement, sightlines, and focal points. This rendering exemplifies that approach, modeling not just light and shadow but also how people would experience the building’s interiors.

Beyond its architectural significance, Burroughs-Wellcome was also the site of a major moment in protest history. It was here that AZT, the world’s first antiretroviral HIV/AIDS drug, was developed. Despite being partially federally funded, it was released at an exorbitant $8,000 per dose, sparking outrage. The drug’s high cost led to protests by ACT UP in the 1980s. In a dramatic act of resistance, activists barricaded themselves inside the very corridors of this Rudolph-designed structure, demanding affordable treatment. Though the building was demolished, its legacy endures — both as an architectural landmark and as a battleground for one of the most critical health justice movements of the 20th century.

23 Beekman Place, Rudoph’s own residence, NY, NY (1967)

One of the most compelling aspects of the exhibition is the section on Rudolph’s experimental interiors from the 1970s. This was a pivotal period in his career when he was no longer being published widely in architectural journals and struggled to realize his large-scale projects. With few buildings being built, Rudolph shifted focus inward, both professionally and personally, turning to smaller-scale domestic projects. He designed private residences for clients in New York and beyond, but most notably, he became his own client at Beekman Place. His four-story penthouse at 23 Beekman Place was a built manifesto, an architectural experiment in real time. Much like Sir John Soane in the 19th century, he used his own home as a test site for ideas, continually modifying and expanding it. Throughout the 1970s, its interiors were featured in House & Garden and other design magazines, showcasing Rudolph’s fusion of high-tech materials with theatrical elements — light panels, Lucite and foam seating. It was a radical shift from his urban megastructures, yet still deeply utopian in its vision. Rudolph’s interiors were embedded within a larger cultural moment — the height of the 70s extravagant aesthetic, disco, the rise of high-tech design, and a golden age of gay liberation. His work paralleled figures like Warhol and Halston, who were shaping the visual culture of the time. Rudolph himself framed his career as spanning both “Christmas lights and the megastructure,” a reflection of his ability to oscillate between extremes. In many ways, Beekman Place was his most intimate and eccentric work — an environment where he played with reflective surfaces, ambient lighting, and unconventional materials like jersey fabric stretched over padded Lucite panels. He described it as “living in a glassy milk bottle,” a dreamlike, immersive world. This period also coincided with his venture into industrial design through Modulightor, the lighting company he co-founded, which provided another outlet for his experimental approach.

The Hirsch House, East 63rd Street, Halston’s residence, NY, NY (1969)

At the same time, the townhouse at East 63rd Street, another key Rudolph project, took on a cultural life of its own after being purchased by Halston. A devoted admirer of Rudolph, Halston had long envisioned living in a “Rudolph-style” townhouse. When the original owners put the East 63rd Street house on the market, he seized the opportunity. It quickly became a legendary setting for Studio 54 after-parties, where Andy Warhol photographed Bianca Jagger draped over Rudolph-designed Lucite furniture, surrounded by floating staircases and ultra-suede upholstery. The house has since passed into the hands of Tom Ford, who recently completed its restoration — a testament to its lasting influence on fashion and design. For the Met, the inclusion of Warhol’s paintings in the exhibition was an opportunity to draw out this cultural intersection. Halston donated an important collection of Warhol paintings in the early 1980s, and while it’s unclear if they ever hung in the Rudolph townhouse, they highlight an important connection between the two figures. Warhol and Rudolph shared an interest in commercial imagery, evident in their work — from the Gulf Oil billboard in Rudolph’s Beekman Place’s kitchen to Warhol’s use of cosmetic surgery ads in his paintings. Both used these images subversively: Warhol in his retail window displays and Rudolph in his interiors, where mass-market materials were recontextualized into something elevated and avant-garde.

Go to the original article here.