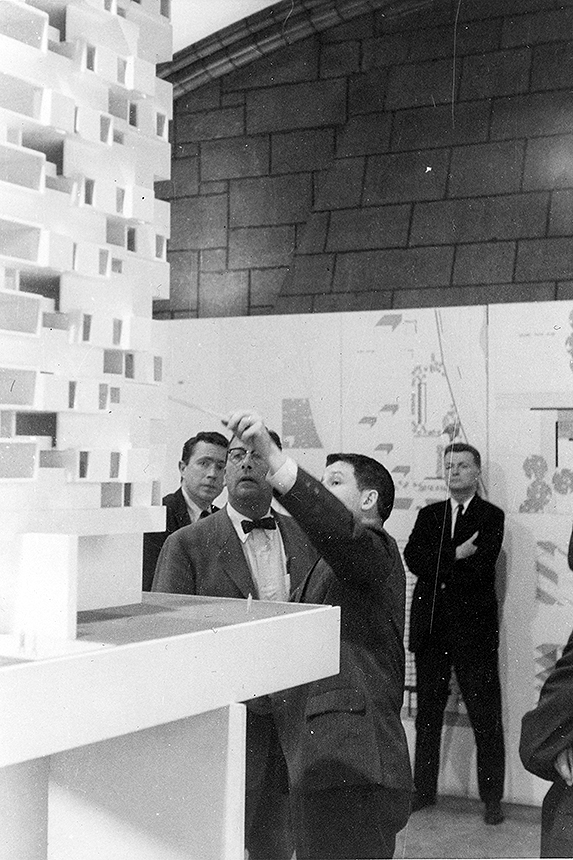

Vincent Scully and Paul Rudolph (with arms crossed), observing Yale student Stanley Tigerman present his design project. Photograph from the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

In his recent memoir, Designing Bridges to Burn, Stanley Tigerman recounts that he was already a practicing architect when he applied to Yale’s architecture program in 1958. Paul Rudolph, department chair, sent an application with a note: “I’m sure I’ll live to regret this.” After two years—thrilling for the quality of education he received directly from Rudolph, grueling for the long hours, shortage of funds, tension, and loss of sleep (plus, in addition to his academic load, working part-time in Rudolph’s New Haven office)—Tigerman graduated. He went on to a colorful and prolific career: designing, building, teaching, curating, writing, and highly articulate (and graphic) hell-raising about all aspects of architecture and urbanism [often in association with his professional and life partner, Margaret McCurry.]

In many ways, Tigerman was a model of how effective (and interesting!) an architect’s life could be: outreaching to every facet of practice, theory, history, and activism. He was one of the most energetic and colorful (and creative) figures of architecture’s last half-century—and could always be counted on to weigh-in with an outspoken (if rarely diplomatic) insight on any issue. [Time did not diminish that fire, as can be shown in his recent comments on the future of a controversial building in his own hometown.]

That candidness of opinion extended to his old teacher-employer-friend, Paul Rudolph—something for which we, at the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, are particularly grateful. In a tribute to his mentor, written on the occasion of a 1997 memorial exhibit at the Architectural League of New York, Tigerman praised outlined his experience with Rudolph and praised his many virtues—and pointedly offered:

Paul Rudolph is an example of a man whose peers never satisfactorily recognized his capacious career; e.g., he never won the Pritzker Prize, the AIA Gold Medal or the Topaz Award, yet others of equal (or questionable) stature somehow accomplished those very ends. No one who knew Paul Rudolph would debate his well known apolitical inclinations to suffer fools gladly, which in turn may have limited his potential for recognition. No matter: that only brings into question reward systems generally . . . There is a theory that it is far better to be appreciated after death, such that, that one's innocence is left intact during life. If the way in which adherents of this discipline exercised selective amnesia related to Paul Rudolph's accomplishments is an example of that theory, leave me out.

[You can read the full text of Tigerman’s memorial remarks at the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s Articles & Writings page, here.]

We mourn the loss of this colleague—an architectural volcano whose stature, like Rudolph’s, will only increase with time and openhearted attention.

Sincerely,

the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Stanley Tigerman 1930-2019. Photograph by Lee Bay, via Wikipedia