Ernst in 2005.

Ernst Wagner, founder and former President of the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture, passed away on Monday, December 23, from complications following a stroke. He was 81 years old.

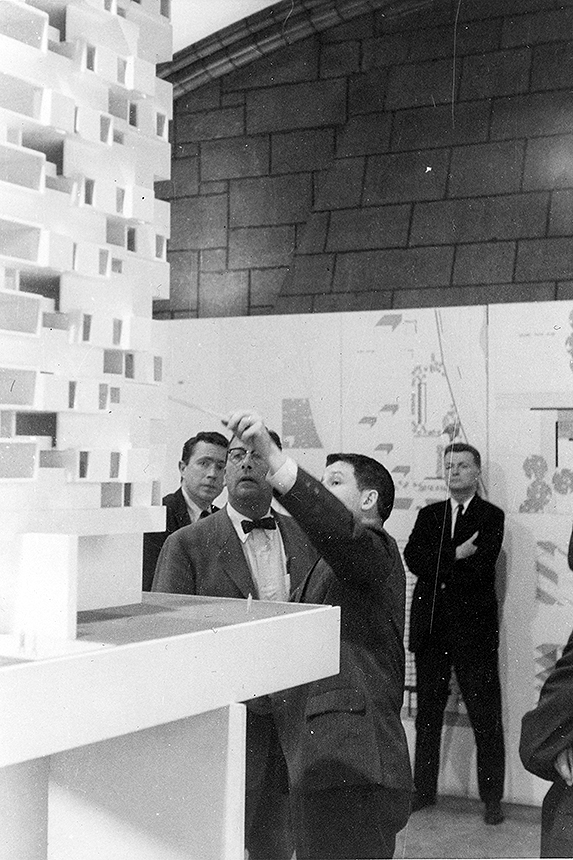

A young Ernst

Ernst Peter Wagner Jr. was born in Liestal, Switzerland on May 26, 1943, the son of Ernst Wagner Sr. and Claire Guggenheim. He grew up in nearby Wenslingen in a house that belonged to the Wagner family for several hundred years. Ernst attended preparatory school in the village of Schiers from 1950 until 1962 and then Teachers College in Basel from 1962 until 1964 graduating with a teaching diploma. From 1964 until 1968 he taught at a high school in Birsfelden, Switzerland.

In November of 1968 he enrolled at the University of Basel to study economics and marketing. Ernst was invited in the summer of 1970 by Swiss Air to travel as an exchange student to New York City, where he stayed in the dorms at Columbia University until returning to Switzerland that August. He graduated with a BA and MBA in 1974, his thesis on the topic of brand choice and brand loyalty.

In July of 1974 he moved from Wenslingen to New York City, where he lived for the rest of his life. He rented an apartment in the Upper East Side on East 81st street before moving to another on Central Park South in April 1975. In July of that year, he was employed at Phillip Brothers on Park Avenue as a trading trainee.

Ernst and Paul

Ernst met Paul Rudolph that year, and in October moved into Paul’s small rental apartment on the top floor of 23 Beekman Place. From that moment, Ernst’s life would be forever intertwined with Paul Rudolph and modern architecture.

Ernst joined Rudolph’s architectural office as a marketing and import purchasing manager in February 1976 just as the firm was developing a line of furniture, lighting fixtures, rugs and other interior accessories. This effort would ultimately lead Paul to create the Modulightor lighting company in August 1976 and make Ernst the company’s Director. Modulightor operated out of the model shop in Rudolph’s architectural office on 57th street until it relocated to SoHo in 1981.

Ernst’s relationship with Paul had a profound effect on Rudolph’s architectural career and legacy. In June 1976, Ernst received a call from the landlord of 23 Beekman Place saying she intended to sell the building. Paul, away on business, was convinced to buy the building after Ernst provided calculations showing how they could afford the $300,000 purchase. Rudolph later designed a quadruplex penthouse addition that became one of his most celebrated designs and a New York City landmark in 2010.

Ernst and Paul with their friend Emily Sherman and others at Beekman Place.

In 1988, the lease for Paul’s architectural office was up for renewal around the same time as Modulightor’s lease for its SoHo production space. Ernst saw a ‘FOR SALE’ sign on the front of the existing building at 246 East 58th Street and suggested to Paul that the building could be purchased and developed as an investment given its proximity to both Rudolph’s office at 57th Street and their residence at 23 Beekman Place.

Recognizing the opportunity, Paul decided to design and construct a new building on the site as a home for Modulightor while his office occupied the floors above. He asked Ernst to collaborate with him on the project. They agreed to jointly finance and own the building, and in February 1989 they purchased the property.

During his lifetime, Rudolph requested the residence at 23 Beekman Place become an architectural study and resource center for the design community of the New York metropolitan area. Inspired by Philip Johnson’s Glass House bequest, he planned to leave the penthouse where he and Ernst lived to the Library of Congress, who would maintain it along with his project archives while Ernst continued to live in it. In 1997, when Paul was sick and near the end of his life, he learned the Library of Congress did not wish to maintain the property. Ernst promised Paul that if the apartment could not be saved, he would turn the Modulightor building into the architectural center Paul had wanted. In response, Paul gave his half of the Modulightor building to Ernst and named him as beneficiary in his will.

In 2001, Ernst founded the Paul Rudolph Foundation to honor Paul’s legacy. After Paul’s death, Ernst moved into the duplex apartment at the top of the Modulightor building. He displayed items that he and Paul had collected over the years throughout the apartment and opened it to visitors. To raise money for the Paul Rudolph Foundation, Ernst rented the apartment out for private events. He also provided the organization office space and access to the apartment for educational and fundraising events.

Ernst talking about Rudolph’s design of the duplex apartment at Modulightor

The Paul Rudolph Foundation grew and in 2014 removed Ernst from the organization after a dispute over the group’s mission. Ernst evicted the Paul Rudolph Foundation from the Modulightor Building and the Paul Rudolph Estate severed all ties with them. Ernst, intent to keep his promise to Paul, created the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation with several of the original members of the Paul Rudolph Foundation. The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation later changed its name to The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture.

In 2010, Ernst self-financed a two story addition to Modulightor inspired by Paul’s original design. Paul had intended to duplicate the design of the third and fourth floor apartments, but Ernst left the floors open so the Institute could display an exhibit of Paul’s work to celebrate his birthday centennial. Ernst later allowed the floors to be used by the Institute to celebrate and educate the public about Paul’s work.

After suffering a stroke, Ernst moved out of the Modulightor building in September 2022. Following its landmark designation, he donated the building and the Modulightor lighting company to the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture in December 2023.

Members of the Paul Rudolph Institute For Modern Architecture with Liz Waytkus, Executive Director of Docomomo US (2nd from right) following the public hearing in support of landmarking the Modulightor Building on in November 2023.

Ernst’s life was dedicated to sharing Paul Rudolph’s work with the public. Whether by designing bespoke light fixtures using Paul’s original specifications, or sitting in the living room at Modulightor sharing stories about his life with Paul, he was always happy to meet people and answer questions. He founded not one, but two organizations dedicated to promoting and preserving Paul’s legacy.

Ernst with his rabbit

Ernst loved rabbits, especially large white ones, which was ironic when Ernst played a video about Paul featuring Phillip Johnson calling Rudolph’s work a ‘three-dimensional rabbit warren.’ Ernst loved to show his rabbit - who went by several different names - to visitors who took as many pictures of it as they did the apartment. Ernst was also fond of cats and would talk about the cat he had shared with Paul at Beekman Place.

Ernst’s life revolved around architects and architecture. Through living with Paul, he saw and understood the importance of good design. While neither a scholar of architecture nor an architect himself, he knew many renowned architects and was quick to share stories about the legendary parties that he and Paul had held at Beekman Place.

A lack of architectural training led some in the profession and academia to dismiss Ernst. Some thought they knew better than Ernst how to protect and preserve Paul’s legacy. Ernst responded in a simple way: opening his home for tours and visitors. He believed being exposed to good design was the best teacher. In the end, Ernst let nothing deter him from keeping his promise to Paul.

Ernst attending the opening of the Paul Rudolph exhibit at the Met Museum in October 2024

Ernst leaves behind a legacy of devotion to Paul’s memory. His last words were “I want our project to continue” and we gave him our promise.

He will be missed and continue to inspire all of us who knew him.