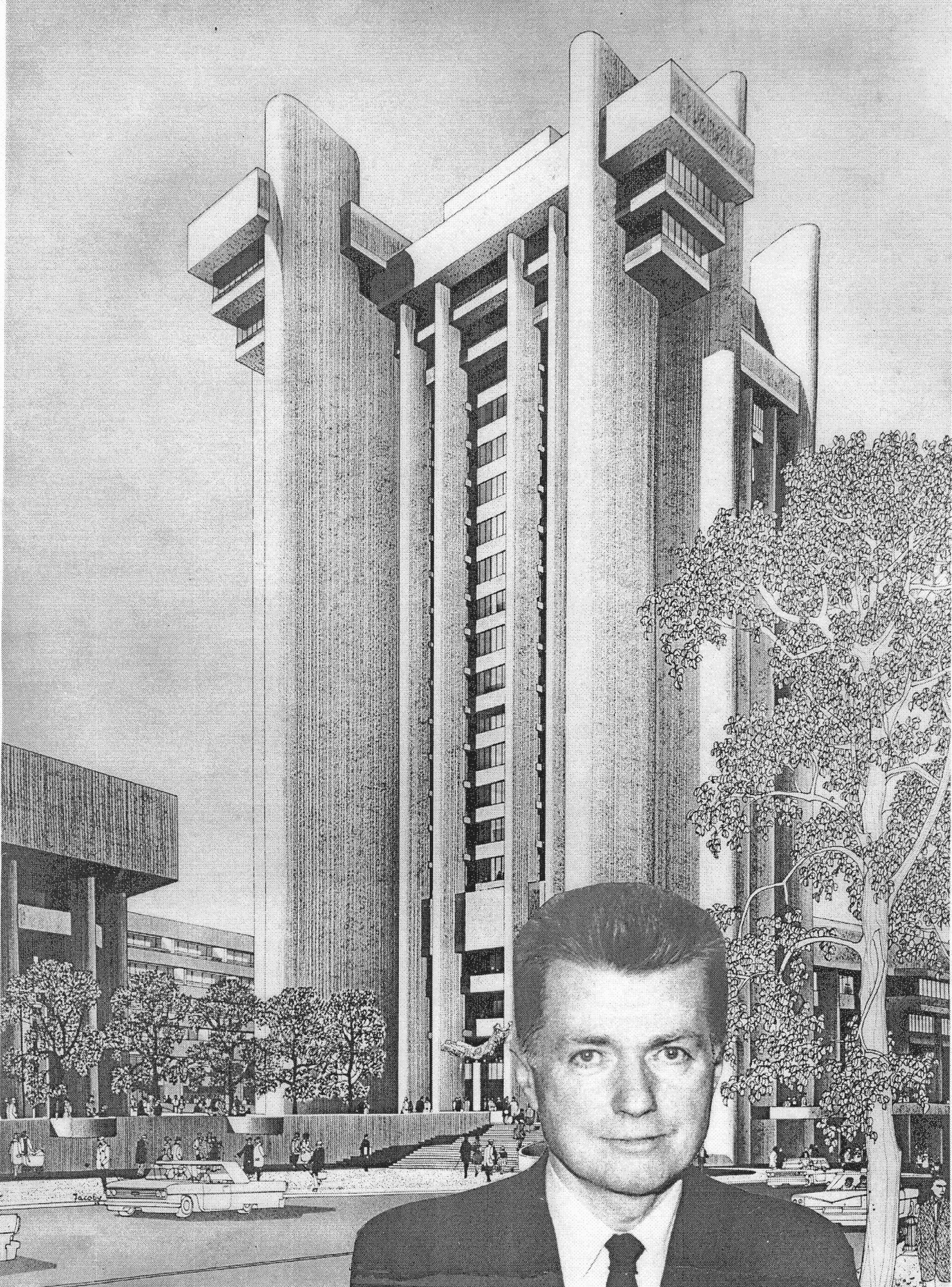

A collage, found in the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation: it shows Rudolph in the foreground, and the background is the tower he designed for the Boston Government Service Center. The drawing of the building is by Helmut Jacoby—one of the “go to” architectural renderers of that era, who was used by almost every major firm in the US. Paul Rudolph was a master perspectivist, and architectural historian Timothy Rohan points out that it was unusual for him to ever use another renderer—but Jacoby’s renderings are often lively with people and activity, and Rudolph had him do the drawing as part of his strategy to win support of the project. © The estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

DISPUTING WHO DESIGNED THE BOSTON GOVERNMENT SERVICE CENTER

If you want to destroy something, the first thing to do is to undercut its value: do everything to lower it’s value and the perception of its integrity.

That propaganda technique is being applied to the Boston Government Service Center, by claiming that it really isn’t a Rudolph design. Yes, the BGSC was a collaborative project, and several architectural firms were involved. But if you know its real history, you’ll also see that Paul Rudolph was the central and true designer: Rudolph gave the complex its organization, form, and essential character.

THE BEST HISTORY OF RUDOLPH’S INVOLVEMENT

The most comprehensive and scholarly study of Paul Rudolph’s life, career, and projects is the one by Timothy M. Rohan: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph, published by Yale University Press. Dr. Rohan is a professor in the art history program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and worked for years, researching in-depth for his monograph on Rudolph. It is the central volume for anyone seeing knowledge of Paul Rudolph’s career, and essential to orienting oneself the cultural and professional contexts in which he worked.

Timothy M. Rohan’s monograph, The Architecture of Paul Rudolph—the most compete and well-researched study of the architect’s life and work—clearly tells the story of Rudolph’s participation in the Boston Government Service Center. Rohan, with scholarly precision, establishes Rudolph’s authorship over the the complex’s design.

No one tells the story of Paul Rudolph’s involvement of the Boston Government Service Center better than Dr. Rohan: he conveys the dramatic way in which Rudolph came to take command of the project. Though the story is told by him with verve, it is fully backed-up by his scholarly research—and we quote several illuminating excerpts from his superb text:

“. . . .As originally conceived, the complex consisted of three independent structures on a boomerang-shaped site cleared by the BRA [Boston Redevelopment Authority] and bounded by Staniford, Merrimac, and New Chardon Streets. In keeping with its policy of promoting diversity of expression, the BRA assigned each building to a different Boston architectural firm: M. A. Dyer with Pedersen and Tilney Company drew Health, Education and Welfare; Shepley,. Bulfinch, Richardson and Abbott received Employment and Social Security; Desmond and Lord were given Mental Health.”

“Hoping to capitalize on Rudolph's reputation, the chairman of the established firm Desmond and Lord, Richard R. Thissen, Jr., hired Rudolph as a design consultant. Thissen, a businessman and not an architect, believed that Rudolph's affiliation with Yale and reputation design skills could raise the profile of the firm. In effect, Rudolph became the firm’s chief designer for the Mental Health Building (and other projects) because there was no one of his caliber at the firm.”

“Although the role of design consultant may have seemed inimical to an upholder of individual genius—and indeed it eventually proved to have its drawbacks—Rudolph was initially enthusiastic because Thissen granted him almost complete design autonomy.”

“Each firm participating in the BGSC project produced its own design for a freestanding building, but they soon realized that the structures were poorly related. Rudolph took this moment as an opportunity to expand his involvement. He convinced all three firms to meet in New Haven. . . . After the members of each firm debated different approaches to collaboration. Rudolph seized their attention theatrically: in a virtuoso display of his design skills and leadership, he took just seconds to sketch a plan in which the buildings would be joined to form a roughly triangular complex enclosing a central courtyard focused on a twenty-three-story tower. Essentially. Rudolph had combined three separate buildings into one large structure.”

Paul Rudolph’s original sketch for the layout of the Boston Government Service Center. The drawing summarizes Rudolph’s overall concept of having a unified set of buildings wrap around the triangular site, with an open plaza in the center. A tower is indicated by the hatched pinwheel-shape toward the middle. © The estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

“Published in many journals along with accounts of the anecdote about its creation, the sketch was celebrated as the mark of Rudolph’s consummate design skills. . . .He was admired for taking action. . . .The final plan for the complex was almost identical to the original pen and ink sketch.”

“Rudolph consolidated his control of the project in subsequent meetings in an equally dramatic and calculated manner. Charles G. Hilgenhurst, director of the BRA's office of Planning. Urban Design and Advanced Projects, recalled that, at the meeting in Boston, Rudolph deliberately upstaged the other firms by arriving late with fully realized drawings. Hilgenhurst recounted, “Twenty minutes late, Paul Rudolph walked onto the stage followed by his crewcut entourage from Yale. After a few brief apologies he unrolled a series of black line prints… The effect was immediate, and he seized advantage of the moment and began to expound the ‘philosophy' of his design. The plan was unchanged—”but now the architecture had emerged.”

Key players in the development of the Boston Government Service Center, surrounding an architectural model of the complex. The model shows the overall design, just as Paul Rudolph had planned it: the buildings follow the perimeter of the site, and with a tower and a courtyard in the center. In the background, along the upper edge of the photo, can also be seen plans of the complex.

From left-to-right: Nathaniel Becker (space planner); Dick Thissen (Desmond & Lord); Charles Gibbons (Government Center Commission); Joseph Richardson (Shepley Bulfinch Richardson & Abbott); Ed Logue (Boston Redevelopment Authority); Jeremiah Sundell (Government Center Commissioner); unidentified; and Paul Rudolph. Most notable in this group is Edward J. Logue: the energetic urban planner and public administrator, who had worked with Paul Rudolph in New Haven. In his position as Director of the Boston Redevelopment Authority, he appointed Rudolph to be the leader of the design team for Boston’s Government Service Center.

“Swayed by Rudolph’s ideas, conviction, reputation, and showmanship, the other firms embraced his plan. Logue named him coordinating architect, granting him the authority to supervise the design of all exteriors.”

Edward J. Logue (1921-2000) was a dynamic urban leader, who led planning and urban revitalization efforts that had powerful effects in several major north-eastern cities: New Haven, Boston, and New York. His work also extended throughout New York State through his leadership of the Urban Development Corporation. Paul Rudolph had worked with him in New Haven— and, when Edward Logue was Director of the Boston Redevelopment Authority, from 1960 to 1967, he appointed Rudolph head of the design team for the entire block of the Boston Government Service Center. Later, again, (as part of the UDC) he’d work with Rudolph on the Shoreline apartment complex in Buffalo. Much more about Logue’s work can be learned from a new, full-length study of his life by Lizabeth Cohen. Photo courtesy of the City of Boston Archives

“. . . The tenor of Rudolph’s relationships with different firms varied. He worked well with the designer of the Employment Security Building, Jean Paul Carlihan from Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson and Abbott, though they frequently got into heated discussions. Rudolph urged Carlihan to make his portion of the complex more sculptural and plastic, like Rudolph’s Mental Health Building. On the other hand, Rudolph found Pedersen and Tilney’s scheme for the tower inconsistent with the other parts of the complex. They were dismissed. and Rudolph redesigned the tower himself. . . .”

A GROUP EFFORT—BUT ALL WORKING THOUGH RUDOLPH’S “VOCABULARY” OF FORM, AND hIS DESIGN CRITERIA

As design leader for the project, Rudolph laid out the planning, formal, and material criteria that all collaborating firms were to follow. Again, Rohan makes this most clear, and we gratefully excerpt again from his monograph:

“At the meeting in Boston that led to his appointment as coordinating architect. Rudolph outlined five design criteria. . . .”

“The first benchmark of the five was a common material and surface treatment for all the buildings. Rudolph chose the corrugated concrete that he had developed for his A & A Building at Yale. . . .”

“The second criterion was massive rectangular piers with rounded corners . . . . to vary from three to twelve feet in diameter and four to seven floors in height. The piers imparted a sense of rhythmic order that helped unify the complex. . . .”

“The third standard was a deep cornice that would unite the rooflines of all three structures. . . .”

“The fourth criterion was the articulation of all service areas, such as elevators, stair towers, and even toilets, with curvilinear shapes and towers. Such articulation would heighten the complex's expressive character. . . .”

“The fifth specification was stepped interior facades. . . . to consist of setback terraces that as a whole would form a bowl- or amphitheater-shaped central courtyard. . . .”

Part of the entry plaza of the Boston Government Service Center—a complex that, throughout, manifests the design intent of Paul Rudolph. The design criteria, which Rudolph defined for the collaborating team, are clearly manifested here. Image courtesy of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, photograph by G. E. Kidder Smith

DESIGNING THE DESIGN

Given the above, it is would be inaccurate to say that Rudolph was not the primary designer of the Boston Government Service Center. He generated the overall approach and layout (what architects call the “parti”) and section, clear rules as to what forms, compositions, and materials were to be used, designed significant portions directly, and lead the team to a complete and coherent design. Moreover if you know Rudolph’s personality and the way he worked—the relationship he required have with any project, if he was going to be involved at all—he wouldn’t let himself be part of a project unless he was the prime designer.