A View of Washington as a Capital - or What Role is Civic Design? - January, 1963

INTRODUCTION

Washington DC has had many plans---the most famous of which is Pierre Charles L'Enfant's original 1791 layout of the city (the "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of the United States...").The other most influential blueprint was the McMillan Plan of 1902, which laid out the vision of the city's national mall (the monumental axis from the White House to the Lincoln Memorial, and adjacent areas). Even with all the planning and good intentions, by the middle of the 20th century much of Washington's built fabric seemed ramshackle: not anything like the proud capitol of a powerful nation. This was pointedly noticed by the about-to-be inaugurated John F. Kennedy: in the motorcade, on the way to his inauguration at the Capitol building, Kennedy noticed how tawdry much of the city looked---and when he became president, he brought attention to the issue. Architects and planners engaged in the discussion, and the January 1963 issue of Architectural Forum was entirely focused on the topic. In that issue, Paul Rudolph offered his analysis of the some of the city's design problems--and his cogent solutions. Below is a transcript of that article.

[Note: in transcribing this text, we have retained most of the grammar, spelling, capitalization, and construction.]

======================================

A View of Washington as a Capital - or What Role is Civic Design?

The one, distinguishing characteristic of Washington architecture and civic design is "monumental dullness"—a term applied not long ago by a certain magazine to a certain Washington building. One cure for dullness is criticism; and one of the most outspoken critics in the U.S. is PAUL RUDOLPH, chairman of the Department of Architecture at Yale, and the architect for some of the finest modern buildings of the postwar years. Here, in brief, are some of his suggestions for Washington:

The Supreme Court is clearly in the wrong place. It should move.

Washington's open spaces are much too open—and much too formless.

The Mall is a mess: its space "leaks out" in all directions, and its flow is interrupted by cross streets.

The Washington Monument, our finest symbol, is surrounded by piles of junk.

Pennsylvania Avenue, the most important street in the country, has no beginning and no end.

Washington's squares are dotted with mediocre and underscaled sculpture, and are generally unusable anyway.

Washington, though neo-Renaissance in its buildings, violates all Renaissance principles in its outdoor spaces.

And most new Washington architecture is ridiculous.

The next words are those of Mr. Rudolph:

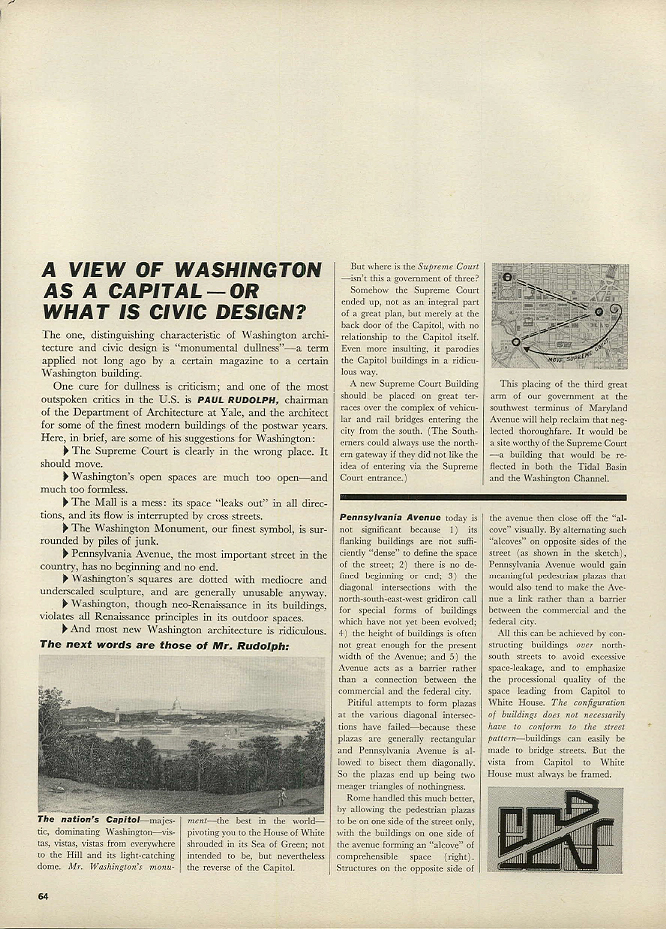

The nation's Capitol—majestic, dominating Washington—vistas, vistas, vistas from everywhere to the Hill and its light-catching dome. Mr. Washington's monument—the best in the world— pivoting you to the House of White shrouded in its Sea of Green; not intended to be, but nevertheless the reverse of the Capitol.

But where is the Supreme Court —Isn't this a government of three?

Somehow the Supreme Court ended up, not as an integral part of a great plan, but merely at the back door of the Capitol, with no relationship to the Capitol itself. Even more insulting, it parodies the Capitol buildings in a ridiculous way.

A new Supreme Court Building should be placed on great terraces over the complex of vehicular and rail bridges entering the city from the south. (The Southerners could always use the northern gateway if they did not like the idea of entering via the Supreme Court entrance.)

This placing of the third great arm of our government at the southwest terminus of Maryland Avenue will help reclaim that neglected thoroughfare. It would be a site worthy of the Supreme Court —a building that would be reflected in both the Tidal Basin and the Washington Channel.

Pennsylvania Avenue today is not significant because 1) its flanking buildings are not sufficiently "'dense" to define the space of the street; 2) there is no defined beginning or end; 3) the diagonal intersections with the north-south-east-west gridiron rail for special forms of buildings which have not yet been evolved; 4) the height of buildings is often not great enough for the present width of the Avenue; and 5) the Avenue acts as a barrier rather than a connection between the commercial and the federal city.

Pitiful attempts to form plazas at the various diagonal intersections have failed—because these plazas are generally rectangular and Pennsylvania Avenue is allowed to bisect them diagonally. So the plazas end up being two meager triangles of nothingness.

Rome handled this much better, by allowing the pedestrian plazas to be on one side of the street only, with the buildings on one side of the avenue forming an "alcove" of comprehensible space (right). Structures on the opposite side of the avenue then close off the "alcove" visually. By alternating such "alcoves" on opposite sides of the street (as shown in the sketch), Pennsylvania Avenue would gain meaningful pedestrian plazas that would also tend to make the Avenue a fink rather than a barrier between the commercial and the federal city.

All this can be achieved by constructing buildings over north-south streets to avoid excessive space-leakage, and to emphasize the processional quality of the space leading from Capitol to White House. The configuration of buildings does not necessarily have to conform to the street pattern—buildings can easily be made to bridge streets. But the vista from Capitol to White House must always be framed.

Washington is a city of ragged edges, gaping holes, freestanding buildings which should be walls defining exterior spaces. The notion that important buildings should stand in a park is unrealistic and an offense to L'Enfant's concept.

The National Capital Planning Commission in its “Plan for the Year 2000” states as a key premise that “the major open spaces of a monumental scale . . . should not be extended or encroached upon.” Fix it? Freeze it? Is it sacred? Nonsense!!! There is no hope for Washington if the present ragged, undefined relationship between the "major open spaces of a monumental scale . . . should not be extended or encroached upon." Fix it? Freeze it? Is it sacred? Nonsense!!! There is no hope for Washington if the present ragged, undefined relationship between the "major open spaces" and buildings is to be regarded as fixed.

The deplorable "no man's land" north and south of the Capitol is an excellent case in point. This area is hopelessly confused, fit for neither car nor pedestrian. The miscellaneous collection of sculpture, fountains, and other niggardly efforts mocks the Capitol, for this bric-a-brac is a collection of isolated events not properly scaled (see below).

This space should properly be a transition area between the Capitol and the various avenues that radiate from it. For instance, Pennsylvania Avenue sorely needs a beginning, an announcement that this is the most important single avenue in the land. Yet the Avenue does not start or end.

The north boundary of Capitol Square should be defined with buildings stepping down the Hill. Instead, the space in which the Capitol sits “leaks out” toward the north.

The Taft Memorial is a travesty—it doesn't know what to do with all that space. And Union Station is much too far away to close the space—Burnham knew very well that his station could never support such a wide vista, and therefore proposed a forecourt to the south of the station.

The Mall is in similar trouble: the sides of the Mall are not defined architecturally, because the space leaks out badly between the internal freestanding buildings. It is essential to plug the gaping holes between these freestanding structures with connecting buildings that could be raised (or opened up in places) to permit north-south streets to pass through and under them. This would create a series of gates to the great Mall. The Museum of History and Technology, the Natural History Building, and the National Gallery' should be joined almost continuously with buildings and arcades to define the northern boundary of the Mall. The southern boundary needs to be defined similarly.

The city that lies to the north and south of the Mall should be revealed occasionally through this screen of "defining buildings"— never at the expense of the directional quality of the Mall itself.

The automobile and bus must be purged from the Mall itself. The flow of the Mall from the Capitol to the Washington Monument is drastically compromised by the many automobile crossings in the north-south direction. The 12th Street underpass (above) is a sordid scandal, and the rise of the Mall at 12th Street to make way for the underpass is a deplorable expediency: the Washington Monument is made to look (from the east) as if it were coming up for air—rather than sitting serenely on its hill.

The Washington Monument was placed loo feet off the north-south axis, for engineering reasons. Congratulations to the engineers: the White House should not be split down the middle!

But why is the great monument surrounded by spalling concrete, cracked macadam, hideous, scraggly grass, cheap wire wastepaper baskets, pseudo-Victorian signs saying "NO," unneeded, unpainted steel fences, factory-like steel hatches to something smack on the axis to the Capitol, left-over lighting standards that conflict with the circle of flags—and, worst of all, a little classical outhouse at the base of the Monument's hill (see far right)?

Suggestion: clean it up. Another suggestion: a parking lot should not form the base to our one, great monument.

Washington's official architecture is usually a six- or eight-storied building treated as a single, monumental one-story structure—large scaled, heavily modeled, light-catching, nonreflective, pavilion-like, often symmetrical. Usually, too, it is an overly pretty version of a Roman temple.

Washington's twentienth-century architecture should not be a sheathed steel frame, but have the integral, sculptural quality of concrete. To say that “monumental structures can be reserved for true monumental purposes [and] a new business-like form can emerge to house operational governmental activities” (as the National Capital Planning Commission has put it) is completely to misunderstand architecture, civic design, and, indeed, the human spirit.

At least 95 percent of the federal cities new building will be for operational governmental activities. How can Washington become more noble, more glorious, indeed more monumental if its Planning Commission believes that most of its buildings should be merely “business-like”?

The capital of Democracy must be more, much more. Every government worker must be reminded that he serves thr nation in a special way. No big business here.

The closest existing twentieth-century equivalent to Washington's bureaucratic buildings is Le Corbusier' s governmental complex at Chandigarh, in India. The High Court Building (85 percent offices) reads from a distance as a one-story high building with a great roof; only upon closer inspection does it reveal the several floors behind the screen of brises Soleil (below).

The principal at Chandigarh is, fundamentally, the same as that frequently followed in Washington; but the means of carrying it out renders the High Court and the General Assembly (right) great works of architecture—while means so often employed in Washington are banal, meaningless, and, suggestive of Hollywood.

Wedding cakes a d World' s Fair valentines are equally imminent— and equally ridiculous and inappropriate. Virility, strength, spirit, and the dynamic—these are the qualities to be sought in the capital of democracy, not prettiness.

Pershing Square (and its area) has within it the seeds of the greatest plaza in the land, for people gather there in times of crises, for celebrations, ceremonies, or other events in the national life.

Unhappily, the existing streets divide the area into five meaningless subareas, each attempting to command attention.

Washington has this insane compulsion to take every little area, find its center of gravity, and build underscaled and mediocre sculpture on that spot.

The Pershing Square area should become a single space. Fortunately, the land slopes toward the southeast; therefore it would be possible to make one great plaza (perhaps on many different levels ) with all vehicular traffic below the pedestrian ways.

A unified design should be adopted for the north, south, and cast walls of Pershing Square, following more or less the present building lines. But only Pennsylvania Avenue should enter the plaza without any obstructions; the other streets should enter the square only through arcades or under buildings that bridge the street. The west side of Pershing Square is of utmost importance;for here the Square becomes simultaneously, a terminus to Pennsylvania Avenue and a forecourt to the White House.

L'Enfant called for a much smaller colonnaded forecourt on the east side of the Capitol (which is its actual entrance), keeping in mind that the Capitol stands some 80 feet above the Mall. It is obvious that L'Enfant's east forecourt is superior in imagination, the plasticity of design, and adaptability to the site to the current chaos of parking lots, bus and tourist unloading, dignitary greeting ground, incomprehensible geometry combined with a semitropical jungle, miscellaneous markers, sculptures, fences, and signs.

What a mess! It's too small to be a park and too large to be a plaza. It is twice the width of the Piazza di San Pietro or the Place de la Concorde; and the ratio of height of building to width of plaza is so great that there is, in fact, no forecourt, no plaza; nor is it truly a group of buildings in a park—nor, indeed, anything comprehensible to anyone.

Washington's squares are generally unsuccessful. Horizontal distances between the buildings are far too great. Although Washington is based on classical and Renaissance concepts for the buildings themselves, these concepts have been ignored in creating the spaces between the actual buildings.

Werner Hegemann and Elbert Peets, in their almost-forgotten book. The Architect's Handbook of Civic Art (above), have a remarkable section devoted to the size of Renaissance plazas. They point out, for example, that “a plaza larger than three times the height of the surrounding buildings is . . . in danger of being of imperfect value as a setting for monumental buildings.”

The new multi-storied buildings, the new scale given by the automobile, the sheer bulk of twentieth-century building's—all this makes Renaissance rides obsolete for the most part. But not for Washington: it should not have towering blocks, it must find its own ways of keeping and augmenting existing compositions. The human eye does not change.

Civic design is the art of assigning various roles to every element of a city; coordinating them so that they form the total environment; providing a three-dimensional framework for continuously adding and subtracting in such a way that every act respects, augments, enhances, and allows the original great idea to fulfill itself. Civic art, not planning.

What roles do buildings play in the cityscape? Clearly, every building must play its part in the whole of civic design is to become eloquent. Traditionally, these roles were well defined by content as well as by dimensions. Today none of this is clear: a building advertising whiskey is much larger (and more expensive) than a church.

The various roles for buildings might be defined as follows:

1) The Focal Building — in Washington, this is, obviously, the nation's Capitol.

2) A building or an element which forms a defined open space for an important building—the loggia of St. Peter's, for example.

3) Flanking buildings that form an enclosure—as Michelangelo's Piazza del Campidoglio.

4) A building which acts as a pivot—like San Antonio di Padova.

5) A building which acts as a transition from one scale or style to another—the group that forms the Piazza Navona in relationship to the church, for example.

6) Buildings that serve as gateways from one space to another— like the Admiralty Arch between Trafalgar Square and The Mall.

7) A building which acts as a bridge—like the Rialto Bridge.

8) A building which acts as a barrier shielding one space from another—in the manner in which the Palazzo Montecitorio separates the Piazza Colonna from the Piazza Montecitorio.

9) Buildings which are essentially encrustations, sculpture, or eruptions on a plane—as at Chandigarh.

10) Buildings that act as free-standing sculptures and are placed in such a way as to create tensions in the space between them—as in the case of the Acropolis.

14) A building which deflects and gives direction to an exterior space—as at Campo San Polo, in Veruce.

15) Buildings formed to create an alcove of space as a transition to a dominant space—the Admiralty Building and the Horse Guards Barracks in London, for example.

16) The low, free-standing building which serves as a focal point in a space defined by taller and neutral buildings- like St. Martin's in the fields.

17) Buildings that produce an enclosure—like Windsor Castle.

And 18) a group of buildings which forms a base for another building—as at Moni St. Michel.

A hierarchy of buildings, like the one I have attempted above, and a clear understanding of the civic design role played by each building, memorial, sculpture, fountain, loggia, vehicular way, bridge, walk, park, etc., is a prerequisite for welding Washington—or any other city—into a whole, rather than a series of isolated, unrelated parts.

The planner’s approach is insufficient to accomplish that which is worthwhile.

Finally, only art can move men to significant action.

Applying these principles, Mr. Rudolph has roughed out (below) some of the possible results:

(A ) The Supreme Court is relocated and placed over existing bridges, to form terminus for Maryland Avenue and a Southern entrance to the city. (B) Maryland Avenue is architecturally defined, and given a "Madison Memorial Gateway" (C) at its Capitol end. (D) The Mall is also given a more decisive form. (E) Pennsylvania Avenue is defined by buildings of uniform height, with plazas forming alcoves on alternating sides. (F) Pershing Square becomes an important terminus, the other one, at the Capitol end (G), being a proposed "FDR Memorial Gateway." The entire area around the Capitol (H) has been scaled down and defined with buildings that link existing structures and spatial sequences that add drama to the approach to the Capitol. The gaping hole (I) toward Union Station has been closed off, but vistas remain toward the station. Gateways and plazas (J ) around the Supreme Court and the Library of Congress are scaled to fit those existing structures.

======================================