The Bauhaus building in Dessau, Germany, designed by the school’s director, Walter Gropius

Photograph by: Lelikron

THE 100th BAUTHDAY

It’s hard to believe, but this year is the Bauhaus’ 100th birthday! Yes, it’s been a century since it was founded in 1919. In the course of three locations in Germany—it was started in Weimar, then to Dessau, and finally in Berlin—the Bauhaus had as many directors: Walter Gropius (in both Weimar and Dessau), Hannes Meyer (in Dessau), and Mies van der Rohe (in Dessau and Berlin). Each had a distinct personality and approach to design---and so each change in leadership also meant significant shifts in the focus and purposes of the school.

DESIGN SUPER-STARS

As important to the Bauhaus’ vitality was the diverse range of teachers which came (and went!) over the school’s history (until it was closed in 1933). Each were to become influential, famous names in the history of design and art. Ones we recognize so well are:

Albers (both Anni and Josef)

Marianne Brandt

Gunta Stölzl

László Mololy-Nagy

Paul Klee

Oskar Schlemmer

Johannes Itten

Wassily Kandinsky

Lyonel Feininger

Marcel Breuer

They became a Who’s Who of modern art and design---and when asked about the great (and sometimes conflicting) diversity of the faculty, Gropius once said:

“There are many branches on the Bauhaus tree, and on them sit many different kinds of birds.”

There’s no need here to go into the full history of the Bauhaus, as it has been archived, recorded, written about, and exhibited extensively over the decades: most notably in Hans Wingler’s magisterial book; and in MoMA’s comprehensive exhibit (and the accompanying catalog) of 2009-2010, done under the leadership and curatorship of Barry Bergdoll. Nor is it necessary to remark extensively on its influence, which can still be seen everywhere—in the design of everything from teacups -to- buildings, and in the way that design and art education is still conducted in classrooms worldwide. Perhaps it is sufficient to say that the Bauhaus—a hundred years since its beginning, has never really ended: is still pervading our lives.

[For this centennial year, there are to be many celebratory events. To find them, just put the word “Bauhaus” with words like “centennial” or “centenary” or “100” or “celebration” into your search-engine, and you’ll find numerous leads.]

THE BAUHAUS’ “GREATEST HITS”

Still, it’s always worth “recharging” ourselves—and refreshing our vision—by taking a look at some of the most memorable images & inventive works which came out of the school. Enjoy these Bauhaus icons:

Oskar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus Symbol:

Image courtesy of Wikipedia

Walter Gropius’ Bauhaus School Building Complex in Dessau:

Image courtesy of Wikipedia.Photo by M_H.DE

Marianne Brandt’s Teapot

Image courtesy of Wikipedia. Photo by: Sailko

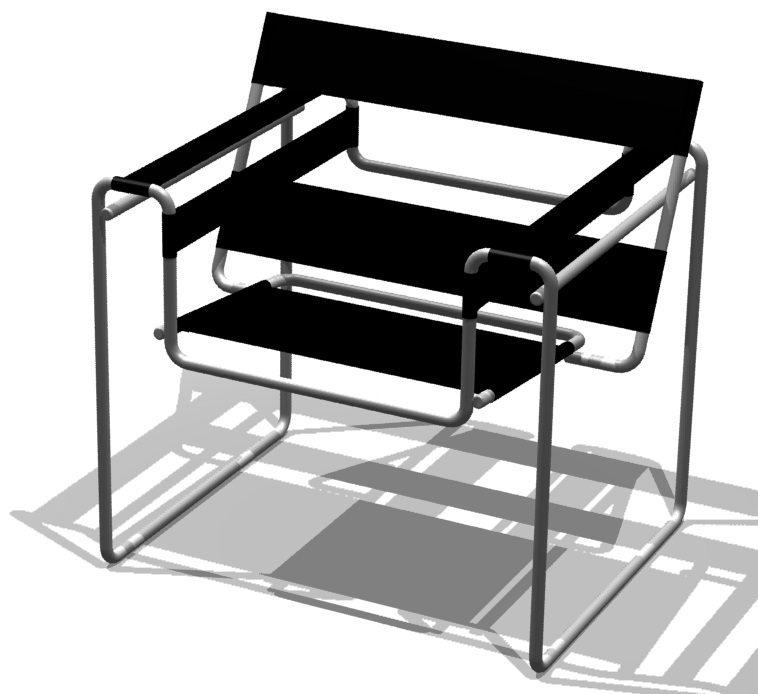

Marcel Breuer’s Wassily Chair:

Image courtesy of Wikipedia, by Borowski

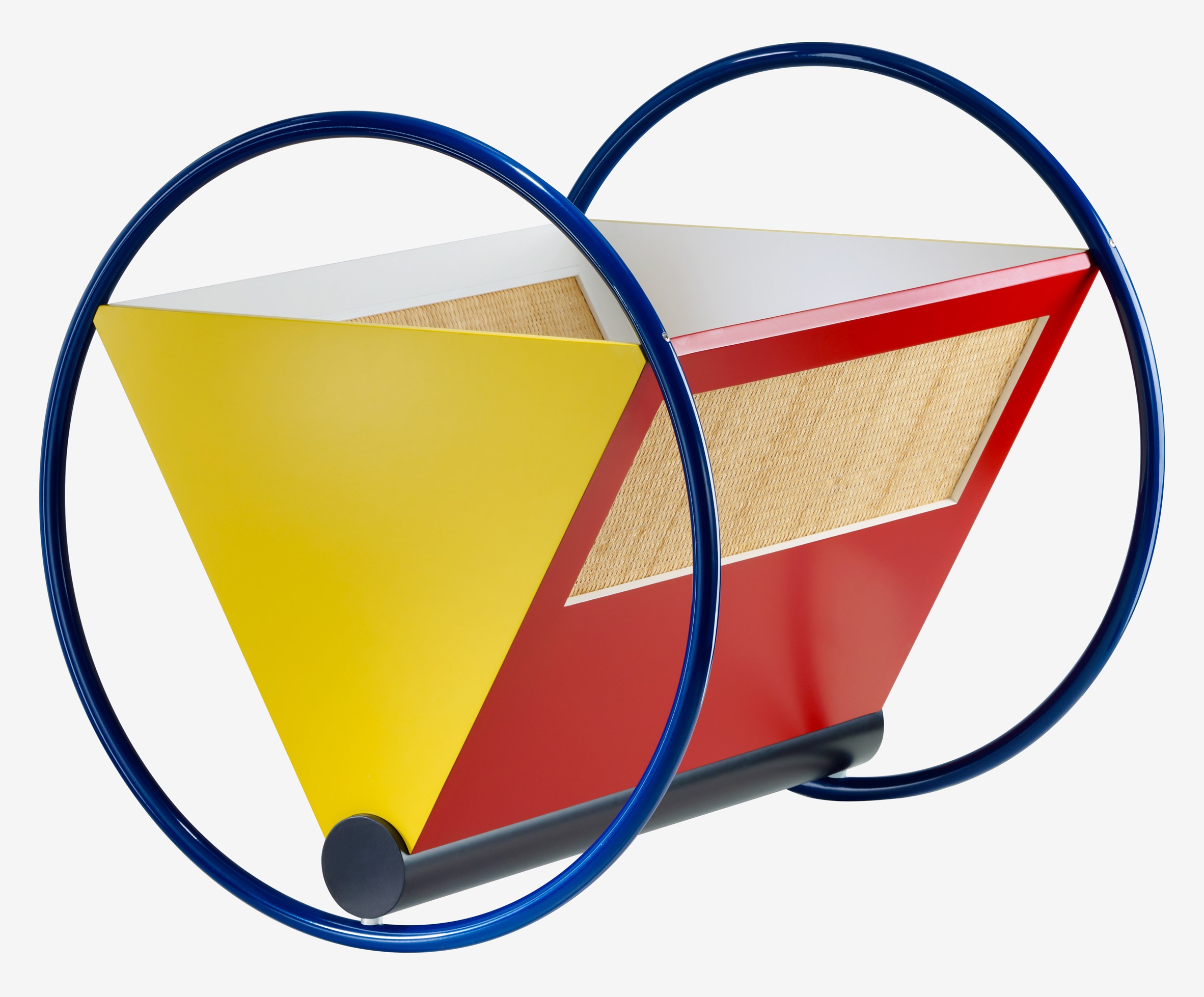

Peter Keler’s Baby Cradle:

Image courtesy of www.tecta.de

Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s and Karl Jakob Jucker’s Table Lamp:

Image courtesy of Wikipedia. Photo by Sailko

Walter Gropius’ Door Hardware:

Image courtesy of Double Stone Steel

Josef Hartwig’s and Joost Schmidt’s Chess Set:

Image courtesy of Eye Magazine

Marcel Breuer’s Cantilever Chairs

Image courtesy of Wikipedia. Photo by Dibe

Oskar Schlemmer’s Design and Choreography for the Triadic Ballet:

Image courtesy of Wikipedia. Photo by Fred Romero

THE BAUHAUS-RUDOLPH CONNECTION

How is Paul Rudolph related to the Bauhaus? The answers are both general and specific.

Broadly speaking, no Modern architect can escape the Bauhaus’ influence. Its approach to form, problem-solving, composition, aesthetics, theory, education, and even idealism are part of the genetic code of Modern Architecture. Rudolph—a man of the mid-20th century architectural generation—was saturated in this, and strongly self-identified with Modernism.

Educationally, Gropius’ work extended to America—and not just via indirect influence, but through his direct teaching. After leaving Germany in 1934, he went to England—and settled in the US in 1937 where he restarted his pedagogical and professional life. Paul Rudolph chose to obtain his graduate (Masters) education at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design—whose architecture program was chaired by Walter Gropius! Even while a student, Rudolph’s special talent was recognized, and he was given a place in the studio which Gropius himself taught.

Paul Rudolph (front-row, at the far right) and his classmates at Harvard.

Photo: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

In later years, people would point out to Rudolph the strong contrast between his own sculpturally expressive work vs. the relentlessly rectilinear “functionalist” buildings of Gropius and his followers (works that were derisively called “Harvard boxes”). But Rudolph acknowledged Gropius, saying that he had given a good basis for architectural work. Moreover, in 1950 Rudolph edited an issue of the French architecture journal, L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui, an issue that was focused on Gropius and his students in the US. Rudolph did not repudiate his teacher.

Finally, one can discern the Bauhaus influence on Rudolph—particularly in work from his Florida years—as in this striking drawing for the Denman Residence:

Axonometric drawing (circa 1946) by Paul Rudolph. Denman Residence, Siesta Kay, Florida.

Courtesy of the Paul Rudolph Archive within the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

Such fresh, clean, design—which embrace (and are drawn with) a clarity of conception—are expressions of the Bauhaus approach to composition and space-making. This is work which, we’d contend, Bauhaus-ian teachers would have been proud to see.